THE BACKGROUND to POLITICAL INSTABILITY in POST-AMIN UGANDA Balamnyeko

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Eastern African Studies Rethinking the State in Idi Amin's Uganda: the Politics of Exhortation

This article was downloaded by: [Cambridge University Library] On: 20 July 2015, At: 20:55 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London, SW1P 1WG Journal of Eastern African Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjea20 Rethinking the state in Idi Amin's Uganda: the politics of exhortation Derek R. Peterson a & Edgar C. Taylor a a Department of History , University of Michigan , Ann Arbor , MI , 48109 , USA Published online: 26 Feb 2013. To cite this article: Derek R. Peterson & Edgar C. Taylor (2013) Rethinking the state in Idi Amin's Uganda: the politics of exhortation, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 7:1, 58-82, DOI: 10.1080/17531055.2012.755314 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2012.755314 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Songs of Soldiers

SONGS OF SOLDIERS DECOLONIZING POLITICAL MEMORY THROUGH POETRY AND SONG by Juliane Okot Bitek BFA, University of British Columbia, 1995 MA, University of British Columbia, 2009 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Interdisciplinary Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) November 2019 © Juliane Okot Bitek, 2019 ii The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the dissertation entitled: Songs of Soldiers: Decolonizing Political Memory Through Poetry And Song submitted by Juliane Okot Bitek in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Interdisciplinary Studies Examining Committee: Prof. Pilar Riaño-Alcalá, (Social Justice) Co-supervisor Prof. Erin Baines, (Public Policy, Global Affairs) Co-supervisor Prof. Ashok Mathur, (graduate Studies) OCAD University, Toronto Supervisory Committee Member Prof. Denise Ferreira da Silva (Social Justice) University Examiner Prof. Phanuel Antwi (English) University Examiner iii Abstract In January 1979, a ship ferrying armed Ugandan exiles and members of the Tanzanian army sank on Lake Victoria. Up to three hundred people are believed to have died on that ship, at least one hundred and eleven of them Ugandan. There is no commemoration or social memory of the account. This event is uncanny, incomplete and yet is an insistent memory of the 1978-79 Liberation war, during which the ship sank. From interviews with Ugandan war veterans, and in the tradition of the Luo-speaking Acholi people of Uganda, I present wer, song or poetry, an already existing form of resistance and reclamation, as a decolonizing project. -

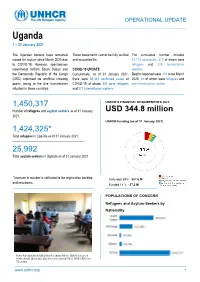

Uganda 1 – 31 January 2021

OPERATIONAL UPDATE Uganda 1 – 31 January 2021 The Ugandan borders have remained These movements cannot be fully verified The cumulative number includes closed for asylum since March 2020 due and accounted for. 14,114 recoveries, 372 of whom were to COVID-19. However, spontaneuos refugees and 229 humanitarian movements to/from South Sudan and COVID-19 UPDATE workers. the Democratic Republic of the Congo Cumulatively, as of 31 January 2021, Deaths reported were 318 since March (DRC) continued via unofficial crossing there were 39,314 confirmed cases of 2020, six of whom were refugees and points, owing to the dire humanitarian COVID-19, of whom, 381 were refugees one humanitarian worker. situation in these countries. and 277 humanitarian workers. cannot be fully verified and accounted 1,450,317 UNHCR’S FINANCIAL REQUIREMENTS 2021: Number of refugees and asylum seekers as of 31 January USD 344.8 million 2021. UNHCR Funding (as of 31 January 2021) 1,424,325* Total refugees in Uganda as of 31 January 2021. 25,992 Total asylum-seekers in Uganda as of 31 January 2021. *Increase in number is attributed to the registration backlog Unfunded 89% - 307.6 M and new-borns. Funded 11 % - 37.2 M POPULATIONS OF CONCERN Refugees and Asylum-Seekers by Nationality Senior four students at Valley View Secondary School, Bidibidi settlement, Yumbe district attend class after schools re-opened. Photo ©UNHCR/Yonna Tukundane www.unhcr.org 1 OPERATIONAL UPDATE > UGANDA / 1 – 31 January 2021 A senior four candidate at Valley View Secondary School, Bidibidi settlement, Yumbe district, studies in preparation for his final examinations. -

Challenges of Development and Natural Resource Governance In

Ian Karusigarira Uganda’s revolutionary memory, victimhood and regime survival The road that the community expects to take in each generation is inspired and shaped by its memories of former heroic ages —Smith, D.A. (2009) Ian Karusigarira PhD Candidate, Graduate School of Global Studies, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, Japan Abstract In revolutionary political systems—such as Uganda’s—lies a strong collective memory that organizes and enforces national identity as a cultural property. National identity nurtured by the nexus between lived representations and narratives on collective memory of war, therefore, presents itself as a kind of politics with repetitive series of nation-state narratives, metaphorically suggesting how the putative qualities of the nation’s past reinforce the qualities of the present. This has two implications; it on one hand allows for changes in a narrative's cognitive claims which form core of its constitutive assumptions about the nation’s past. This past is collectively viewed as a fight against profanity and restoration of political sanctity; On the other hand, it subjects memory to new scientific heuristics involving its interpretations, transformation and distribution. I seek to interrogate the intricate memory entanglement in gaining and consolidating political power in Uganda. Of great importance are politics of remembering, forgetting and utter repudiation of memory of war while asserting control and restraint over who governs. The purpose of this paper is to understand and internalize the dynamics of how knowledge of the past relates with the present. This gives a precise definition of power in revolutionary-dominated regimes. Keywords: Memory of War, national narratives, victimhood, regime survival, Uganda ―75― 本稿の著作権は著者が保持し、クリエイティブ・コモンズ表示4.0国際ライセンス(CC-BY)下に提供します。 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ja Uganda’s revolutionary memory, victimhood and regime survival 1. -

A Foreign Policy Determined by Sitting Presidents: a Case

T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI ANKARA, 2019 T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI SUPERVISOR Prof. Dr. Çınar ÖZEN ANKARA, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................ i ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................... iv FIGURES ................................................................................................................... vi PHOTOS ................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE UGANDA’S JOURNEY TO AUTONOMY AND CONSTITUTIONAL SYSTEM I. A COLONIAL BACKGROUND OF UGANDA ............................................... 23 A. Colonial-Background of Uganda ...................................................................... 23 B. British Colonial Interests .................................................................................. 32 a. British Economic Interests ......................................................................... -

Detailed Curriculum Vitae Prof. Moses Muhumuza

Curriculum Vitae Assoc. Prof. Moses Muhumuza (PhD)* Bachelor of Science with Education (Biology & Chemistry), Master of Science (Biology)- Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Uganda, and Doctor of Philosophy (Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences)- University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa *For correspondence: Email: [email protected], Tel: +256772565565/+256756723711 August 2020 Page 1 of 39 Curriculum vitae- Assoc. Prof. Dr. Moses Muhumuza [Bsc. Ed. (Bio.&Chem.)-MUST, Msc. (Bio.)-MUST, PhD (APES)-WITS] SUMMARY OF THE ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL PROFILE Assoc. Prof. Dr. Moses Muhumuza was trained as a graduate teacher by profession specializing in Biology and Chemistry teaching subjects. He eventually advanced his career to focus on Biological Sciences. He has a Masters of Science Degree in Biology specializing in Natural Resource Management, and a PhD in Animal, Plant, and Environmental Sciences focusing on social aspects of rural communities neighboring protected areas in an African context. He also has certificates in project planning and management, project monitoring and evaluation, data analysis and various short course trainings. His expertise stretches across a wider spectrum in both the natural and social sciences. By virtue of teaching at secondary school and university levels, he has engaged in a variety of teaching and research methodologies and accumulated experience in developing self-study materials, writing competitive research proposals and informative research reports. He currently lectures introductory and advanced courses in Biological Sciences, Social science for Conservation, Science education, Climate Change, and Research Methods at Mountains of the Moon University. He has supervised to completion over 30 students’ research projects in sciences and liberal arts both at undergraduate and postgraduate level. -

Political Question Doctrine in Uganda

Political Question Doctrine in Uganda An analysis of the technicalities on the realization of the freedoms of expression, association and Assembly in Uganda J. Oloka-Onyango MAKERERE UNIVERSITY Acknowledgment This paper was written for Chapter Four Uganda by J. Oloka-Onyango, a Professor of Law at Makerere University, School of Law. Research assistance was provided by Dorah Kankunda, Dan Bill Opio, and Joseph Byomuhangyi. Copyright © 2017 Chapter Four Uganda All rights reserved. Chapter Four Uganda is an independent not-for-profit organisation dedicated to the protection of civil liberties and promotion of human rights for all. We promote human dignity and advance rights through robust, strategic and non-discriminatory legal response. For more information, please visit: http://chapterfouruganda.com The Production of this paper was generously funded by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). 01 05 Introduction Association and its 4 Protection and Violation 24 02 06 Technicalities and the The Question of Assembly PQD: The Good, the 30 Bad and the Ugly 6 Table of Contents 03 07 The Constitutional Conclusion Framework and the 34 Movement towards Inclusion 10 04 Freedom of Expression, Media Rights and Access to Information (A2I) 4.1 Expression and Media 15 Rights 4.2 Access to Information 19 01 Introduction 4 Political Question Doctrine in Uganda nsofar as a great deal of the Law is concerned with access to and the delivery of Justice, it is something of a surprise how much of the Law is in fact devoted to its subversion. Nowhere is the subversion of Justice more apparent than in the use of technicalities by lawyers in order to prevent a matter from being fully heard by the Icourts of law. -

Tooro Kingdom 2 2

ClT / CIH /ITH 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 0090400007 I Le I 09 MAl 2012 NOMINATION OF EMPAAKO TRADITION FOR W~~.~.Q~~}~~~~.P?JIPNON THE LIST OF INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE IN NEED OF URGENT SAFEGUARDING 2012 DOCUMENTS OF REQUEST FROM STAKEHOLDERS Documents Pages 1. Letter of request form Tooro Kingdom 2 2. Letter of request from Bunyoro Kitara Kingdom 3 3. Statement of request from Banyabindi Community 4 4. Statement of request from Batagwenda Community 9 5. Minute extracts /resolutions from local government councils a) Kyenjojo District counciL 18 b) Kabarole District Council 19 c) Kyegegwa District Council 20 d) Ntoroko District Council 21 e) Kamwenge District Council 22 6. Statement of request from Area Member of Ugandan Parliament 23 7. Letters of request from institutions, NOO's, Associations & Companies a) Kabarole Research & Resource Centre 24 b) Mountains of the Moon University 25 c) Human Rights & Democracy Link 28 d) Rural Association Development Network 29 e) Modrug Uganda Association Ltd 34 f) Runyoro - Rutooro Foundation 38 g) Joint Effort to Save the Environment (JESE) .40 h) Foundation for Rural Development (FORUD) .41 i) Centre of African Christian Studies (CACISA) 42 j) Voice of Tooro FM 101 43 k) Better FM 44 1) Tooro Elders Forum (Isaazi) 46 m) Kibasi Elders Association 48 n) DAJ Communication Ltd 50 0) Elder Adonia Bafaaki Apuuli (Aged 94) 51 8. Statements of Area Senior Cultural Artists a) Kiganlbo Araali 52 b) Master Kalezi Atwoki 53 9. Request Statement from Students & Youth Associations a) St. Leo's College Kyegobe Student Cultural Association 54 b) Fort Portal Institute of Commerce Student's Cultural Association 57 c) Fort Portal School of Clinical Officers Banyoro, Batooro Union 59 10. -

Collapse, War and Reconstruction in Uganda

Working Paper No. 27 - Development as State-Making - COLLAPSE, WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION IN UGANDA AN ANALYTICAL NARRATIVE ON STATE-MAKING Frederick Golooba-Mutebi Makerere Institute of Social Research Makerere University January 2008 Copyright © F. Golooba-Mutebi 2008 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Working Paper, the Crisis States Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Working Paper, of any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. Crisis States Working Papers Series No.2 ISSN 1749-1797 (print) ISSN 1749-1800 (online) 1 Crisis States Research Centre Collapse, war and reconstruction in Uganda An analytical narrative on state-making Frederick Golooba-Mutebi∗ Makerere Institute of Social Research Abstract Since independence from British colonial rule, Uganda has had a turbulent political history characterised by putsches, dictatorship, contested electoral outcomes, civil wars and a military invasion. There were eight changes of government within a period of twenty-four years (from 1962-1986), five of which were violent and unconstitutional. This paper identifies factors that account for these recurrent episodes of political violence and state collapse. -

Democracy Or Fallacy: Discourses Shaping Multi-Party Politics and Development in Uganda

Journal of African Democracy and Development Vol. 1, Issue 2, 2017, 109-127, www.kas.de/Uganda/en/ Democracy or Fallacy: Discourses Shaping Multi-Party Politics and Development in Uganda Jacqueline Adongo Masengoa Abstract This paper examines the discourses shaping the introduction of multi-party politics in Uganda and how it is linked to democracy and development. The paper shows that most Ugandans prefer multi-party politics because they link it to democracy and development. This is why when the National Resistance Army/Movement (NRA/M) captured power in 1986 and multi-party politics was abolished, there was pressure from the public to reinstate it through the 2005 referendum in which the people voted in favour of a multi- party system. The paper also examines the role played by Ugandan politicians and professional middle class such as writers and literary critics (local agency) in the return of multi-party politics in Uganda. It explores their contribution of in re-democratising the Ugandan state and argues that despite the common belief that multi-party politics aids democracy and development, it might not be the case in Uganda. Multi-party politics in Uganda has turned out not to necessarily mean democracy, and eventually development. The paper grapples with the question of what democracy is in Uganda and/ or to Ugandans, and the extent to which the Ugandan political arena can be considered democratic, and as a fertile ground for development. Did the return to multi- party politics in Uganda guarantee democracy or is it just a fallacy? What is the relationship between democracy and development in Uganda? Keywords: Multi-party politics, democracy, Fallacy, Uganda 1. -

The Lord's Resistance Army in Central Africa

The Lord’s Resistance Army in Central Africa A short timeline May 2009 Yoweri Museveni, leader of AP Photo Alice Lakwena, a young Acholi woman from northern the National Resistance 1986 Uganda declares herself to be under the orders of Christian Army, overthrows President spirits, creates the rebel group the Holy Spirit Mobile Forces, Milton Obote and becomes and declares war against Museveni’s government. president of Uganda. After taking power, President Another rebel group, the Uganda People’s Democratic Army, Museveni, a southerner, or UPDA, launches a rebellion against Museveni. Joseph begins systematically President Yoweri Museveni Kony, reportedly a cousin of Alice Lakwena, serves as a rooting out ‘enemies’ hailing Catholic preacher to the UPDA. from the Acholi ethnic group of northern Uganda. Kony, despite claiming to AP Photo defend the rights of the Lakwena is defeated, and she flees to Kenya. Kony recruits her 1987-88 Acholi in northern Uganda remaining forces and forms the Uganda People’s Democratic by waging war against the Christian Army, which later becomes the Lord’s Resistance Ugandan government, Army, or LRA. 1991 launches a campaign of extreme brutality against them, murdering and LRA Leader Joseph Kony IRIN The Sudanese government mutilating civilians, pillaging begins to provide direct villages, and abducting children to fill his ranks. support to the LRA. In return, the LRA supports 1993-4 Khartoum’s war against the Sudan People’s Liberation IRIN Army in southern Sudan. SPLA Rebels in Southern Sudan 1996 The U.S. government Protected village in northern Uganda places the LRA Stating its intent to prevent looting and abductions by the on a list of terrorist LRA, the Ugandan government forces more than two million organizations. -

The Power of Oil Charting Uganda’S Transition to a Petro-State

RESEARCH REPORT 10 Governance of Africa’s Resources Programme M a r c h 2 0 1 2 The Power of Oil Charting Uganda’s Transition to a Petro-State Petrus de Kock and Kathryn Sturman About SAIIA The South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA) has a long and proud record as South Africa’s premier research institute on international issues. It is an independent, non-government think-tank whose key strategic objectives are to make effective input into public policy, and to encourage wider and more informed debate on international affairs with particular emphasis on African issues and concerns. It is both a centre for research excellence and a home for stimulating public engagement. SAIIA’s research reports present in-depth, incisive analysis of critical issues in Africa and beyond. Core public policy research themes covered by SAIIA include good governance and democracy; economic policymaking; international security and peace; and new global challenges such as food security, global governance reform and the environment. Please consult our website www. saiia.org.za for further information about SAIIA’s work. About the Govern A n c e o f A f r I c A ’ S r e S o u r c e S P r o G r A m m e The Governance of Africa’s Resources Programme (GARP) of the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA) is funded by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The programme contributes to policy governing the exploitation and extraction of Africa’s natural resources by assessing existing governance regimes and suggesting alternatives to targeted stakeholders.