Inca Culture at the Time of the Spanish Conquest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Interrelation and Regional Patterning in the Department of Puno, Southern Peru Jean Morisset

Document généré le 30 sept. 2021 04:15 Cahiers de géographie du Québec Urban interrelation and regional patterning in the department of Puno, Southern Peru Jean Morisset Volume 20, numéro 49, 1976 Résumé de l'article Le département de Puno s'inscrit autour du lac Titicaca (3 800 m au-dessus du URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/021311ar niveau de la mer) pour occuper un vaste plateau (l'altiplano) ainsi que les DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/021311ar hautes chaînes andines (la puna) et; déborder au nord vers le bassin amazonien (la selva). Aller au sommaire du numéro En utilisant à la fois des informations recueillies lors d'enquêtes sur le terrain et des données de recensement (1940 et 1961), cet essai poursuit un double objectif: on a tenté d'analyser d'une part, l'évolution et l'interdépendance des Éditeur(s) principaux centres du département de Puno pour proposer, d'autre part, une régionalisation à partir des structures géo-spatiales et des organisations Département de géographie de l'Université Laval administratives. De plus, on a brièvement traité de la nature des agglomérations et on a réalisé une analyse quantitative ISSN regroupant 30 variables reportées sur les 85 districts du département. 0007-9766 (imprimé) L'auteur conclut en suggérant que toute planification est un processus qui doit 1708-8968 (numérique) aboutir à un compromis entre des composantes spatio-économiques (planificaciôn tecno-crética) et des composantes socio-culturelles (planificaciôn Découvrir la revue de base). Citer cet article Morisset, J. (1976). Urban interrelation and regional patterning in the department of Puno, Southern Peru. -

Generación, Alcohol Y Parentesco

1 2 Agradecimientos Esta investigación se realizó gracias al apoyo económico del Fondo Concursable de Becas para la Investigación del Instituto Nacional sobre Abuso de Drogas de los Estados Unidos (NIDA) y la Comisión Interamericana de Control de Drogas (CICAD) de la organización de Estados Americanos (OEA). En primer lugar agradecemos a nuestras madres y padres: Giselle Amador, Nubia Jara y Longino Salazar; a nuestras familias por el apoyo y comprensión brindada a lo largo de todo el proceso de esta Tesis. A nuestro Comité Asesor: Carlos Garita, Enrique Hernández y Luis Jiménez A todos nuestros amigos y amigas, a los que formaron parte de los cursos de la licenciatura y a quienes nos ayudaron en la recolección de información y discusión. Especialmente a Demalui Amighetti, María José Escalona, Gloriana Guzmán, Josua Montenegro, Gustavo Rojas y Andrea Touma. Así como a las Hamacas Music por el uso del espacio, el apoyo e interés en nuestra investigación: Carlos Zeledón, Victorhugo Castro y Jamal Irias A la Escuela de Antropología y su Comisión de Trabajos Finales de Graduación. A nuestra filóloga: Maritza Quesada Último pero no menos importante, un gran agradecimiento a los y las estudiantes de la UCR que participaron de las entrevistas y grupos de discusión, por su tiempo y por el valioso conocimiento y experiencias que han sido realmente la estructura medular de nuestra investigación. Y a todas las otras personas que de una u otra forma han colaborado en este producto final. Finalmente gracias a Dios. Jah bless. Namaste. 3 Resumen El consumo de bebidas alcohólicas es un hecho social que existe en casi todas las culturas del mundo. -

New Age Tourism and Evangelicalism in the 'Last

NEGOTIATING EVANGELICALISM AND NEW AGE TOURISM THROUGH QUECHUA ONTOLOGIES IN CUZCO, PERU by Guillermo Salas Carreño A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Professor Bruce Mannheim, Chair Professor Judith T. Irvine Professor Paul C. Johnson Professor Webb Keane Professor Marisol de la Cadena, University of California Davis © Guillermo Salas Carreño All rights reserved 2012 To Stéphanie ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was able to arrive to its final shape thanks to the support of many throughout its development. First of all I would like to thank the people of the community of Hapu (Paucartambo, Cuzco) who allowed me to stay at their community, participate in their daily life and in their festivities. Many thanks also to those who showed notable patience as well as engagement with a visitor who asked strange and absurd questions in a far from perfect Quechua. Because of the University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board’s regulations I find myself unable to fully disclose their names. Given their public position of authority that allows me to mention them directly, I deeply thank the directive board of the community through its then president Francisco Apasa and the vice president José Machacca. Beyond the authorities, I particularly want to thank my compadres don Luis and doña Martina, Fabian and Viviana, José and María, Tomas and Florencia, and Francisco and Epifania for the many hours spent in their homes and their fields, sharing their food and daily tasks, and for their kindness in guiding me in Hapu, allowing me to participate in their daily life and answering my many questions. -

Sustainability Report 2011

Sustainability Report 2011 Fl FTY YEARS 1962 2012 CERTIFIED BY THE CRF INSTITUTE Index Letter to our stakeholders 8 Our ID 13 Our businesses 14 Enel worldwide 16 Group structure 18 Organizational Chart 20 Energy numbers 22 A sustainable year 24 Methodological note 30 How this Report has been prepared 31 Parameters of the Report 32 Chapter 1 - The Enel Group: identity, values, results 35 1.1 Our identity 36 1.2 A sustainable business 37 1.2.1 Strategic priorities 37 1.2.2 Climate Strategy 38 1.2.3 2012-2016 Sustainability Plan 40 1.3 2011 results 48 1.3.1 Operating results 48 1.3.2 Economic and financial results 51 1.3.3 Value created for stakeholders 53 1.4 Governance 55 1.4.1 Our shareholders 55 1.4.2 The corporate governance system 56 1.4.3 Risk management 67 Dossier - Innovation 68 Chapter 2 - Responsibility, transparency, ethics 79 2.1 The principles underpinning our actions 80 2.1.1 The three pillars of our corporate ethics 80 2.1.2 Lessons on ethics 83 2.1.3 Our key commitments 85 2.2 In line with our stakeholders 89 2.3 The network that multiplies our energy 94 2.4 What they say about us 97 2.4.1 Enel in the media 97 2.4.2 Brand Equity 98 2.4.3 Prizes and awards 99 Chapter 3 - The energy of our people 101 3.1 Our commitments 102 3.2 The numbers 104 3.3 People development 106 3.3.1 Recruitments and selection 107 3.3.2 Value creation 108 3.3.3 Training 110 3.4 Occupational health and safety 112 3.4.1 Objective: Zero accidents 112 3.4.2 Protecting health at Enel 118 3.5 Quality of life in the Company 122 3.5.1 Listening and discussing -

The King's Banner

Home Page THE KING’S BANNER Christ the King Lutheran Church, Houston, Texas Volume 68, Number 1, January, 2013 Evangelical Lutheran Church in America Festival of the Epiphany January 6 Blessing of Homes on Twelfth Night Intergenerational Celebration The Twelfth Night of Christmas and Epiphany Day Join us on Sunday, January 6 to end the twelve days of Christmas and also offer an occasion to bless our own homes celebrate the festival of the Epiphany where God dwells with us in our daily living. A of Our Lord. Worship will begin in the printed rite of blessing and chalk will be supplied to narthex with the blessing of the nave all who wish to bless their home and inscribe their and inscription above the door. Between entrance door with 20+CBM+13. When the magi the early and late services all are invited saw the shining star stop overhead, they were filled to a time of fellowship with storytelling, with joy. “On entering the house, they saw the child candle making, star crafting, and the with Mary his mother.” (Matthew 2:10-11) finding of the baby in the King’s Cake. Annual Meeting Part II 8:30 a.m. Early service begins in the narthex Part II of the annual congregational meeting will be 9:30 a.m. Coffee and King’s Cake in the courtyard held on February 3, at 12:30 p.m. in the parish hall. 9:50 a.m. Epiphany story for adults and children in the parish hall On the agenda are the 10:15 a.m. -

Menu El Avion Con Cambios.Cdr

Menu Phones: 2777-3378 / 4000-1542 Manuel Antonio, Costa Rica Salads / Ensaladas w/o tax w/ 13% tax & 10% service Caesar Salad / Ensalada César ...................................¢4,467 ¢5,495 strips of grilled chicken breast over crisp romaine lettuce, home made garlic croutons, grated parmesan cheese & traditional Caesar dressing pechuga de pollo en trozos a la plancha sobre lechuga romana, crutones hechos en casa, queso parmesano y el tradicional aderezo César House Salad / Ensalada de la Casa.............................¢4,061 ¢4,995 mixed lettuces, heart of palm, sweet corn, onion, sliced cucumber & tomato with honey-mustard dressing lechugas mixtas, corazón de palmito, maíz dulce, cebolla, pepino y tomate con aderezo mostaza-miel Gorgonzola Salad / Ensalada Gorgonzola.................¢4,305 ¢5,295 mixed lettuces, green apple, raisins, crumbled gorgonzola cheese drizzled with balsamic vinaigrette lechugas mixtas, manzana verde, pasas, coronado con queso gorgonzola y vinagreta de balsámico Yellowfin Tuna Salad / Ensalada de Atún Aleta Amarilla...................................¢5,118 ¢6,295 lightly seared slivers of yellowfin tuna served over a bed of mixed lettuces, heart of palm, sweet corn, tomato, onion & cucumber ~ presented with sesame oil dressing atún aleta amarilla en trozos sobre lechugas mixtas, corazón de palmito, maíz dulce, tomate, cebolla y pepino ~ con aderezo aceite de ajonjolí Calamari Salad / Ensalada de Calamar......................¢4,874 ¢5,995 rings of calamari marinated with kalamata olives, diced celery, sweet -

REVIS. ILLES I IMPERIS14(2GL)1 19/12/11 09:08 Página 87

REVIS. ILLES I IMPERIS14(2GL)1 19/12/11 09:08 Página 87 ALONSO DE SOLÓRZANO Y VELASCO Y EL PATRIOTISMO LIMEÑO (SIGLO XVII) Alexandre Coello de la Rosa Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF) [email protected] ¡Profundamente lo ponderó [Marco Tulio] Cicerón, o achaque enve- jecido de la naturaleza, que a vista de la pureza, no faltan colores a la emulación! Sucede lo que al ave, toda vestida de plumaje, blanco (ar- miño alado) que vuela a la suprema región del aire, y a los visos del Sol parece que mil colores le acentúan la pluma. Apenas pretende el criollo ascender con las alas, que le dan sus méritos, cuando buscan- do colores, aunque a vista del Sol les pretender quebrar las alas, por- que no suban con ellas a la región alta del puesto de su patria.1 Estas palabras, escritas en 1652 por el oidor de la Audiencia de Lima y rector de la Uni- versidad Mayor de San Marcos, don Alonso de Solórzano y Velasco (1608-1680), toda- vía destilan parte de su fuerza y atrevimiento. A principios del siglo XVII la frustración de los grupos criollos más ilustres a los que se impedía el acceso a los empleos y honores reales del Virreinato peruano, en beneficio de los peninsulares, despertó un sentimiento de autoafirmación limeña.2 La formación de ese sentimiento de identidad individual fa- voreció que los letrados capitalinos, como Solórzano y Velasco, redactaran discursos y memoriales a través de los cuales se modelaron a sí mismos como «sujetos imperiales» con derecho a ostentar honores y privilegios.3 Para ello evocaron la idea de «patria» como una estrategia colectiva de replantear las relaciones contractuales entre el «rey, pa- dre y pastor» y sus súbditos criollos.4 1. -

Romans in Cumbria

View across the Solway from Bowness-on-Solway. Cumbria Photo Hadrian’s Wall Country boasts a spectacular ROMANS IN CUMBRIA coastline, stunning rolling countryside, vibrant cities and towns and a wealth of Roman forts, HADRIAN’S WALL AND THE museums and visitor attractions. COASTAL DEFENCES The sites detailed in this booklet are open to the public and are a great way to explore Hadrian’s Wall and the coastal frontier in Cumbria, and to learn how the arrival of the Romans changed life in this part of the Empire forever. Many sites are accessible by public transport, cycleways and footpaths making it the perfect place for an eco-tourism break. For places to stay, downloadable walks and cycle routes, or to find food fit for an Emperor go to: www.visithadrianswall.co.uk If you have enjoyed your visit to Hadrian’s Wall Country and want further information or would like to contribute towards the upkeep of this spectacular landscape, you can make a donation or become a ‘Friend of Hadrian’s Wall’. Go to www.visithadrianswall.co.uk for more information or text WALL22 £2/£5/£10 to 70070 e.g. WALL22 £5 to make a one-off donation. Published with support from DEFRA and RDPE. Information correct at time Produced by Anna Gray (www.annagray.co.uk) of going to press (2013). Designed by Andrew Lathwell (www.lathwell.com) The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development: Europe investing in Rural Areas visithadrianswall.co.uk Hadrian’s Wall and the Coastal Defences Hadrian’s Wall is the most important Emperor in AD 117. -

Bio-Filtration of Helminth Eggs and Coliforms from Municipal Sewage for Agricultural Reuse in Peru

Bio-filtration of helminth eggs and coliforms from municipal sewage for agricultural reuse in Peru Rosa Elena Yaya Beas Thesis committee Promotors Prof. Dr G. Zeeman Personal chair at the Sub-department of Environmental Technology Wageningen University Prof. Dr J.B. van Lier Professor of Anaerobic Wastewater Treatment for Reuse and Irrigation Delft University of Technology Co-promotor Dr K. Kujawa-Roeleveld Lecturer at the Sub-department of Environmental Technology Wageningen University Other members Dr N. Hofstra, Wageningen University Prof. Dr M.H. Zwietering, Wageningen University Prof. Dr C.A. de Lemos Chernicharo, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Brazil Dr M. Ronteltap, UNESCO-IHE, Delft This research was conducted under the auspices of the Graduate School of SENSE (Socio-Economic and Natural Sciences of the Environment). II Bio-filtration of helminth eggs and coliforms from municipal sewage for agricultural reuse in Peru Rosa Elena Yaya Beas Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. Dr A.P.J. Mol, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Wednesday 20 January 2016 at 1.30 p.m. in the Aula. III Rosa Elena Yaya Beas Bio-filtration of helminth eggs and coliforms from municipal sewage for agricultural reuse in Peru 198 pages. PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2016) With references, with summaries in English and Dutch ISBN 978-94-6173-494-5 IV V Abstract Where fresh water resources are scarce, treated wastewater becomes an attractive alternative for agricultural irrigation. -

Honorable Mayor and City Council From

STAFF REPORT TO: HONORABLE MAYOR AND CITY COUNCIL FROM: MARTIN D. KOCZANOWICZ, CITY ATTORNEY SUBJECT: CONSIDERATION OF POLICY FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF "MAYOR EMERITUS" TITLE BACKGROUND At the July 6 and August 17. 2009 Council meetings, the possibility of establishing a Mayor Emeritus title was agendized for discussion. Shortly before the August meeting Council received a request from a proponent of the potential policy, withdrawing his request for consideration. Council tabled the item. Recently Council has again asked to have the matter agendized for further discussion. Attached to this staff report are the prior staff reports and research materials obtained by staff at that time. (Attachment 1) By agendizing the item for this meeting, the Council may discuss the proposed policy and, depending on the outcome of such discussion, provide additional direction to staff. DISCUSSION As a summary of prior research the title of "Emeritus" is generally associated with the field of academia. According to a dictionary definition, it is an adjective that is used in the title of a retired professor, bishop or other professional. The term is used when a person of importance in a given profession retires, so that his/her former rank can still be used in his/her title. This is particularly useful when establishing the authority of a person who might comment, lecture or write on a particular subject. The word originated in the mid-18th century from Latin as the past participle of emereri, meaning to "earn ones discharge by service". It is customarily bestowed by educational institutions on retiring/retired faculty members or administrators in recognition of their long-term service. -

La Identidad Turística En Los Pobladores Del Distrito De Chacas Para El Turismo Cultural, Ancash, 2020

FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS EMPRESARIALES ESCUELA PROFESIONAL DE ADMINISTRACIÓN EN TURISMO Y HOTELERÍA La identidad turística en los pobladores del distrito de Chacas para el turismo cultural, Ancash, 2020 TESIS PARA OBTENER EL TÍTULO PROFESIONAL DE: Licenciada Administración en Turismo y Hotelería AUTORA: Romero Lopez, Lucia Victoria (ORCID: 0000-0001-5153-6487) ASESOR: Mg. Huamaní Paliza, Frank David (ORCID: 0000-0003-3382-1246) LÍNEA DE INVESTIGACIÓN: Patrimonio y Recursos Turísticos LIMA - PERÚ 2020 Dedicatoria El siguiente trabajo de investigación está dedicado a mis amados Padres, que apresar de las dificultades supieron formarme con valores y hacer de mí una mujer de bien, a ellos principalmente dedico este trabajo de investigación, sin dejar de lado a Dios quien me ha acompañado en todo el proceso sin dejarme decaer por las adversidades. Así mismo dedico este trabajo a mi persona por haberme servido de ejemplo de que todo se puede. ii Agradecimientos A mis padres y hermano por haberme apoyado y animado en todo el proceso de investigación. A mi gran amiga Kely Vega por ser mi soporte incondicionalmente. Al clamado y respetado docente Justiniano Roca Sáenz, por ser un ejemplo a seguir para mí y ser la persona quien inculco en mi ese sentido de pertenencia hacia lo nuestro y ser una de las razones para estudiar esta hermosa carrera, así mismo a los docentes Isaac Quiroz Aguirre, Jesús Zaragoza Guzmán, Magda Romero Vino, Manuel P. Falcón Roca, de igual forma a las demás personas quienes colaboraron en mi trabajo de campo y a pesar de no habernos conocido con anterioridad como con la Sra. -

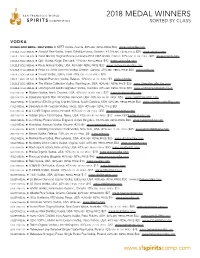

2018 Medal Winners Sorted by Class

2018 MEDAL WINNERS SORTED BY CLASS VODKA DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL / BEST VODKA ■ NEFT Vodka, Austria 49% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $30 www.neftvodka.com DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Absolut Raw Vodka, Travel Retail Exclusive, Sweden 41.5% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $26 www.absolut.com DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Casa Maestri Original Premium Handcrafted 1965 Vodka, France 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $20 www.mexcor.com DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ CpH Vodka, Køge, Denmark 44% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $40 www.cphvodka.com DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Party Animal Vodka, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $23 www.partyanimalvodka.com DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Polar Ice Arctic Extreme Vodka, Ontario, Canada 45% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $28 www.corby.ca DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Simple Vodka, Idaho, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $25 DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Svayak Premium Vodka, Belarus 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $4 www.mzvv.by DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ The Walter Collective Vodka, Washington, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $28 www.thewaltercollective.com DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Underground Spirits Signature Vodka, Australia 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $80 www.undergroundspirits.co.uk GOLD MEDAL ■ Bedlam Vodka, North Carolina, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $22 www.bedlamvodka.com GOLD MEDAL ■ Caledonia Spirits Barr Hill Vodka, Vermont, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $58 www.caledoniaspirits.com GOLD MEDAL ■ Charleston Distilling King Charles Vodka, South Carolina, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $25 www.charlestondistilling.com GOLD MEDAL ■ Deep Ellum All-Purpose Vodka, Texas, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $21 GOLD MEDAL ■ EFFEN® Original Vodka, Holland 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $30 www.beamblobal.com