THIS DISPOSITION IS NOT CITABLE AS PRECEDENT of the TTAB Mailed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

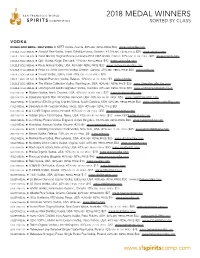

2018 Medal Winners Sorted by Class

2018 MEDAL WINNERS SORTED BY CLASS VODKA DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL / BEST VODKA ■ NEFT Vodka, Austria 49% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $30 www.neftvodka.com DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Absolut Raw Vodka, Travel Retail Exclusive, Sweden 41.5% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $26 www.absolut.com DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Casa Maestri Original Premium Handcrafted 1965 Vodka, France 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $20 www.mexcor.com DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ CpH Vodka, Køge, Denmark 44% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $40 www.cphvodka.com DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Party Animal Vodka, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $23 www.partyanimalvodka.com DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Polar Ice Arctic Extreme Vodka, Ontario, Canada 45% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $28 www.corby.ca DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Simple Vodka, Idaho, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $25 DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Svayak Premium Vodka, Belarus 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $4 www.mzvv.by DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ The Walter Collective Vodka, Washington, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $28 www.thewaltercollective.com DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Underground Spirits Signature Vodka, Australia 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $80 www.undergroundspirits.co.uk GOLD MEDAL ■ Bedlam Vodka, North Carolina, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $22 www.bedlamvodka.com GOLD MEDAL ■ Caledonia Spirits Barr Hill Vodka, Vermont, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $58 www.caledoniaspirits.com GOLD MEDAL ■ Charleston Distilling King Charles Vodka, South Carolina, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $25 www.charlestondistilling.com GOLD MEDAL ■ Deep Ellum All-Purpose Vodka, Texas, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $21 GOLD MEDAL ■ EFFEN® Original Vodka, Holland 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $30 www.beamblobal.com -

The New York Herald. Whole No

THE NEW YORK HERALD. WHOLE NO. 8769. MORNING EDITION-TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 11, 1860.-TRIPLE SHEET. PRICE TWO CENTS. CALIFORNIA MINKS. CALIFORNIA MINKS AMrSKMKVra. AMVdRMKNTN. AMUHKMBNTfl AMVtiKMHN'I'S. PTtHB ATTORNEY OKNKRAJ. AND THRMKW ALU ADEN. mund Randolph was. and U, their standing oounael In Califor¬ theatre _LO*8 GARDEN. nia. were retalaed bv thoae AURA^KEKNWR TllKATRB or Mimic -tbovatork-oortmm. X Talk* Hod. J. 8. Black, Aitorner U«MrAl Dnltad Mam- They claimants to obtain fro »the WALLACE'SMr. WALLACE /mm M. KUob Lnm a LAURA KKKNE'8 THEATRE. hiiric t...In of the lmmrn»* aiicceea, mm Rib.A ease of that mine, which lolled Males tta patent for that ranoho. They claimed Al- Mr. LMSTE& WALLACE Munu ORKAT Academy eonaeqnance hbrtof Matameut of the madeo for their ol and the Btap 8U0CEM compliance Willi uumeruiut application* for an early i Uf persoa may substantiate by an examination of the vola- private tenia Dtatrtet Ooart ap- NOTICE LAST F'UR NIGHTS _ OREaT huctemi mlnoua tegtlmooy now before tte United Rtalaa oourtt In OaU- Wproved that elaim. The very same gentlemen are employed MB. W Al.LACK last four nights . GRBAt BUCOkWN IL TROVATOBK. Xurnle shows:. Hou, and paid by the public money, to sne out an Injunction announce to hi. paimn. and Ih. pub*, .enemlly LAST FOUR NIGHTS gkkat ructbhh , , oh cost and In the name of the United LAST For the director* beg to announce LA TRAVIATA for Thundag That la IMA when California waa a provtooe of Mextoo, ^¦r Htuss. restraining ^Beji^lo R NIGHTS UKKaT 8UCVBMH evening next *nd for Andrea a Mexican ofhonr, travelling la tha country, the owners at Aimaden from working, because the mine be¬ ABOVE ESTABLISHMENT LAHT FOUR NIGHTS GREAT RUOCRdS Caallllero, oa a to the to THIK (TDRBDAY) BVENIXQ. -

Drinks & Cocktails

DRINKS & COCKTAILS BEACH BESTS (Served On The Rocks) Diablo Rojo (Rum or Vodka with te rojo and limon) Junquillal Sunset (Tequila, orange juice, grenadine and a splash of soda) Pura Vida Punch (Spieced Rum, Malibu, tropical juices) Re-Pete (Malibu and Mirinda) Mer-mAID (Vodka, Blue Curacao and fresh limonaid) Great Canadian Caesar (Made with clamato juice and all the fixings) COSTA RICAN FAVS (Served On The Rocks) Agua de Mangle (Rum, Tamarindo juice, fresh limon juice) Caipirinha (Cacieque mulled with fresh limon & sugar) Chili Guaro Shot (Our take on the Costa Rican favorite) Margarita (Tequila, Triple Sec, fresh limon juice & simple syrup) Mojito (White Rum, fresh mint, fresh limon juice & simple syrup) BLENDED COCKTAILS Mango Tango Meltdown (Ameretto, Spieced Rum, mango & strawberry) Pina Colada (White Rum, coconut milk, coconut cream, pineapple juice) Margarita (Tequila, Triple Sec, fresh limon juice & simple syrup) Mojito (White Rum, fresh mint, fresh limon juice & simple syrup) Daiquiri (White Rum, strawberry & limon) Ask for Mixed Cocktails Sodas, juices, fresh limonaid, ice coffee, coffee, tea also available Curated Whiskey Selections Available Ask your server for options FLIP OVER FOR WINE & BEER WINES & BEERS SANGRIA Red or White (wine, juice, triple sec, mixed fruits and a splash of soda) RED WINES Cabernet Sauvignon Merlot Pinot Noir Malbec WHITE WINES Chardonnay Sauvignon Blanc Pinot Grigio DOMESTIC Pilsen Imperial Imperial Silver Imperial Light CRAFT NATIONAL Donmingo 7 Blueberry Wheat (Tano Manso) Domingo 7 Amber Bock (Buho) Domingo 7 Floripondia (Blossom Ale) Domingo 7 #7 Golden Ale Domingo 7 Lagarta Domingo 7 IPA Conejo Mago FLIP OVER FOR DRINKS & COCKTAILS. -

The Realities of Looting in the Rural Villages of El Petén, Guatemala

FAMSI © 1999: Sofia Paredes Maury Surviving in the Rainforest: The Realities of Looting in the Rural Villages of El Petén, Guatemala Research Year : 1996 Culture : Maya Chronology : Contemporary Location : Petén, Guatemala Site : Tikal Table of Contents Note to the Reader Introduction Purpose, Methodology, and Logistics Geographical Setting Rainforest Products and Seasonal Campsites Who are the Looters? Magic and Folklore Related to Looting Voices in the Forest Tombs with Riches, Tombs with Magic Glossary of local words Local Knowledge about Maya Art and History Local Classification of Precolumbian Remains Local Re-Utilization of Archaeological Objects Destruction vs. Conservation. What are the Options? Cultural Education in Guatemala The Registration of Archaeological Patrimony Acknowledgements List of Figures Sources Cited Abbreviations Note to the Reader The present article is intended to be used as an informational source relating to the role of local villagers involved in the process of looting. For reasons of privacy, I have used the letters of the Greek alphabet to give certain individuals fictitious names. Words that refer to local mannerisms and places related to the topic, which are in the Spanish or Maya languages, are written in italics. The names of institutions are in Spanish as well, and abbreviations are listed at the end of the article. The map is shown below. Submitted 02/01/1997 by : Sofia Paredes Maury 2 Introduction This study was supported in part by funds from the Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. (FAMSI, Crystal River, FL). It is an introductory research that focuses on the extraction and commercialization of Precolumbian artifacts by the rural villagers of El Petén, and the role of the community and site museums in Guatemala. -

TROPICAL COCKTAILS Casa Club SANGRIA FROZEN DAIQUIRIS

TROPICAL COCKTAILS Pura Vida - Guaro - Triple Sec - Cranberry Juice - $7 Guaro Sour - Guaro Cacique - Lemon Juice – Sugar - $6 Mojito - Ron Blanco – Mint - Lemon Juice - Club Soda – Sugar - $7 Caipirinha - Cachaça 51 - Lemon Juice – Sugar - $6 Punta Catedral – Guaro – Cas Purée – Pineapple - Cilantro - $6 Bahama Mama - Rum - Tropical Fruit Punch - Coconut Cream - $9 Banana Bungee - Rum - Creme de Banana - Coconut Cream - Evaporated Milk - $10 Pacific Breeze - Vodka -Triple Sec – Lemonade - Sprite - $8 Bird of Paradise - Vodka - Peach Liqueur – Pineapple - Cranberry Juice - $9 Mai Tai - Rum - Triple Sec – Amaretto – Tropical Fruit Blend - $11 Cosmopolitan - Vodka - Cranberry Juice - Triple Sec - Lime Juice - $7 Cosmopolitan Deluxe – Vodka – Cranberry Juice – Grand Marnier - $9 Luna’s Iced Tea – Absolut Vodka – Peach Liqueur – Iced Tea - $9 Gaia Sunset – Guaro – Banana Liqueur – Pineapple & Orange Juice – Grenadine - $11 Guajito – Guaro – Midori – Lemon Juice - Sugar – Mint - $9 BBC – Bailey’s & Banana Liqueurs – Fresh Banana – Coconut Cream - $9 Mudslide – Bailey’s & Kahlua Liqueurs – Vodka – Vanilla Ice Cream - $9 Casa Club SANGRIA By The Pitcher - Red or White - $25 FROZEN DAIQUIRIS Your Choice Of: Lemon – Strawberry - Blackberry Guanábana – Banana – Mango – Pineapple – Papaya – Passion Fruit - $6 MARGARITAS Coconut Margarita - Silver Tequila – Triple Sec – Coconut Cream - $9 Blackberry Margarita – Blackberry Purée – Cointreau – Silver Tequila – Triple Sec - $9 Gold Margarita - Gold Tequila - Triple Sec – Grand Marnier - $11 Frozen Mango -

El Ritual Tropical Cocktails

El Ritual Tropical Cocktails Fantasia Tropical Malibu rum, green mint liqueur, orange juice & pineapple juice Ron malibu, licor de menta verde, jugo de naranja y jugo de piña Hilton Papagayo Guaro cacique, amaretto liqueur, cranberry juice & pineapple juice Guaro cacique, licor amaretto, jugo de cranberry y jugo de piña Mojito Bacardi blanco, lemon wedges, crushed mint leaves, sugar & soda water Bacardi blanco, cuadritos de limón, hierba buena, azúcar y soda Caipirinha Cachaça, lemon juice & brown sugar Cachaça, jugo de limón y azúcar moreno Papagayo Special Bacardi blanco, lizano amaretto, orange juice & sprite Bacardi blanco, amaretto lizano, jugo de naranja y sprite Bahama Mama Bacardi blanco, coconut cream, fruit punch, banana & grenadine Bacardi blanco, crema de coco, jugo de frutas, banana y granadina Pura Vida Guaro cacique, orange juice & green mint liqueur Guaro cacique, jugo de naranja y licor de menta verde Hawaiian Cocktail Gordon’s gin, cointreau, orange juice & pineapple juice Ginebra gordon’s, cointreau, jugo de naranja y jugo de piña Magic Parrot Smirnoff vodka, blue curacao liqueur, banana liqueur & orange juice Vodka smirnoff, licor de blue curacao, licor de banana, y jugo de naranja Monte del Barco Malibu rum, pineapple juice, & cranberry juice Ron malibu, jugo de piña y jugo de cranberry Prices do not include 10% Service Charge & 13% Sales Tax El Ritual International Cocktails Mint Julep Jack daniel’s, mint leaves & sugar Jack daniel’s, hojas de menta y azúcar refinada Sangria Red wine, brandy, orange juice, lemon -

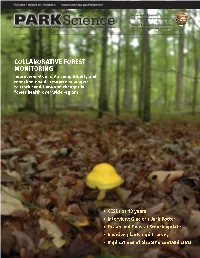

Park Science Volume 26, Number 2, Fall 2009

Fall 2009 • Volume 26 • Number 2 www.nature.nps.gov/ParkScience PARK SCIENCE • VOLUME 26 • NUMBER 2 • FALL 2009 National Park Service PARKScience U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Integrating Research and Resource Management in the National Parks Office of Education and Outreach PARKScience Integrating Research and Resource Management in the National Parks Volume 26 • Number 2 • Fall 2009 www.nature.nps.gov/ParkScience ISSN 0735–9462 From the Editor Published by U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Lakewood, Colorado Continuity Director, National Park Service Jon Jarvis Associate Director, Natural Resource I am thrilled to publish a case study about a resource inventory and Stewardship & Science Bert Frost condition assessment of desert springs at Saguaro National Park. The Director, Natural Resource Program Center authors credit the fi rst edition of Park Science with inspiration for this George Dickison work. Published in 1980, this inaugural issue highlighted the intensive 11- Editor day gathering of researchers and resource managers to “take the pulse” of Jeff Selleck Natural Resource Program Center, Offi ce of Education a wilderness drainage lying mostly within Olympic National Park. Three and Outreach years later the pulse model was adopted at Sequoia–Kings Canyon na- Associate Editor tional parks, where it was repeated in 1994 to illuminate resource changes Katie KellerLynn Writer-Editor, Colorado State University (cooperator) over that period. I was lucky to be a participant in the second Sequoia pulse study, covering the story as the new editor of Park Science. I know Contributing Editor Betsie Blumberg how stimulating the pulse approach can be on account of its daily surveys, Writer-Editor, Pennsylvania State University (cooperator) nightly group progress reports, and the opportunities for professional Copyeditor/Proofreader growth through meaningful collaboration and fi eldwork. -

SOMMELIER GUIDELINES 2021 Association De La Sommellerie Internationale ASSOCIATION DE LA SOMMELLERIE INTERNATIONALE COPYRIGTH © ASI 2021

SOMMELIER GUIDELINES 2021 association de la sommellerie internationale ASSOCIATION DE LA SOMMELLERIE INTERNATIONALE COPYRIGTH © ASI 2021 CONTENTS BLIND TASTING GRID .............................................................................................................12 COCKTAIL SERVICE GRID ........................................................................................................18 FOOD & BEVERAGE PAIRING GRID .........................................................................................21 3 FOOD & BEVERAGE PAIRING GRID .........................................................................................24 PRECISION POURING SPARKLING WINE GRID .....................................................................28 WINE SERVICE GRID ................................................................................................................association 31 COMMUNICATIONde AND APPEARANCE la sommellerie .................................................................................. 35 DECANTING ..............................................................................................................................internationale 38 SPARKLING WINE GRID ...........................................................................................................44 IDENTIFYING BEVERAGES WITH GUIDELINESS ...................................................................48 GUIDELINE EXAMPLES FOR BASIC IDENTIFICATION OF BEVERAGES .............................. 53 GUIDELINES ASSOCIATION DE LA SOMMELLERIE -

Catholic Telegraph .

CATHOLIC TELEGRAPH . .. "In ]'OJ eee§ s~1l,rij§ Un ii tas. in Du toi is Libe:n.·tas, in 0 In nibu s Cal'i t as." PTJBLISHED llY CONAHAN & BROTHER.) REV. EDWARD PURCELL, EDITOR. (TERMS, $2,SO PER ANNUM, IN ADVANCE. VOLUME XVn.-NO. 5 L CINCINNATI, TI-IURSDAY, DECEMBER ~l, 1848. "VHOLE NUMBER 884. ".,...'"577 . ¥ Frorn the Tablet. tics ure not likely to approve (If C::ltholic February last, I entered the Congregation Ir.racked his own jol,es, at weddings, and THE "LIVES OF THE SAINTS." works of any kind. The Council of Trent of the Or~tory, I. submitted.l';ly wor ~;: t.o the w~s sponsor at the christeni.ngs for n:ore 'Ve allllou oce in another column, with did l1 ot.':!onsLJ.lt the ,opinions, n.ol' minister to Fathers WIth a VieW to obtall1lDg theJ]' JUdg- 1ch tl dren tha n any othp.r man 10 the pal'lsh. great regret, that this most valuable publi. the whims of heretiCS, whom Jt condemned, m ent on its continu ance. They, for "ari- He could recite whole pllges of Pasto ri ni, 'eatiOlY is s<lspcndp,d , ' Me regret t h is fer Ale~ander VIr., ~heD he condemned Jan- (OUS reasons, put off'their determination till Iand as for Co.lumbkill's prophecies, he· had t he sake of lhe thousand subscribe rs and sel1lsm, did not lespect the f~e llngs of Its the close ofthe)'ear, and u pon what grounds Ith em all at hIS fingers' ends. Shandy was the tre bled numbur of readers. -

Download Our Menu

The hook We Support Ceviche - 100% Costa Rican Spicy Calamari Fish Fried just how you like it. Shrimp Fish and shrimp mix Fish Tales Dorado ngers from the one that didn't Tuna Sashimi get away. If we have it! Chicken Fingers Tuna Tataki You’ll need a hand with this one. Like we said, if we have it! Wings Ahi Sliders Pick your favorite avor: ree baby burgers: Tuna let with Bualo, BBQ or Ginger Citrus. caramelized onion, Japanese slaw and our secret sauce. Edamame Steamed soy beans and they’re good for ya! Spring Rolls Super crispy little bites! Chips & Salsa 100% homemade. Gyozas Potstickers, choose your favorite avor... Guacamole pork, shrimp or vegetarian. Holy moly, it’s lots of guacamole. Avocado Egg Rolls Crunchy, munchy... stued full of avocados. Hot & Tasty Crab Dip e winner! Served with fresh bread or tortilla chips. Tempura Green Beans Says it all... served with spicy shrima dip. Classic: Spinach & Artichoke Dip Shrimp Wonton Served with fresh bread or tortilla chips. Stued with shrimp and cream cheese. Beef Sliders Buffalo Shrimp ree baby burgers, made fresh topped Nice and spicy. with caramelized onions. Scampi Nachos’ Super Dip Our house style. Refried beans topped with chiken, salsa ranchera, cheese, greens, salsa mexicana, avocado & sour cream. Vegetarian dish Prices include sales and service taxes. We accept colones and dollars. Soups Seafood Chowder Chicken Vegetable Yes, the white one! Just like mama said. Black Bean Tortilla An earthy delight from Costa Rica 100% Aztec (Sorry, no beans) Salads Greenhouse Mexican Chop Salad Fresh, local greens and oven baked croutons. -

Brandies Liqueurs and Others Whiskies / Whiskeys White Spirits

WHITE SPIRITS 260. Distillers’ Single Malt Scotch – Up to 12 Years 100. Vodka IN CLASS CODE FIELD ON ENTRY FORM, PLEASE INDICATE: 261. Distillers’ Single Malt Scotch – 13 to 19 Years 262. Distillers’ Single Malt Scotch – 20 Years and Older 100-A POTATO 100-B WHEAT 100-C RYE 100-D GRAPE 100-E SUGAR CANE 100-F FRUIT 263. Distillers’ Single Malt Scotch – No Age Statement 100-G NEUTRAL 100-H CORN 100-I OTHER FOR ALL SINGLE MALT SCOTCH ENTRIES, ADD REGION DESIGNATION TO CLASS CODE IN CLASS CODE FIELD ON ENTRY FORM: 101. Flavored Vodka A-HIGHLANDS B-LOWLANDS C-ISLAY D-ISLANDS E-SPEYSIDE F-CAMPBELLTOWN 110. Aquavit 120. Gin 121. Old Tom Gin 270. Independent Merchant Single Malt 122. Genever 280. Blended Malt Scotch Whisky 123. Flavored Gin 124. Barrel-Aged Gin BRANDIES 130. Soju/Shochu 131. Baijiu 300. Cognac VS/Three Star or Equivalent 140. White Rum 301. Cognac VSOP or Equivalent 141. Dark/Gold Rum 302. Cognac XO or Equivalent 142. Extra-Aged Rum – 5 Years and Older 303. Cognac Extra-Aged/Vintage 143. Over-Proof Rum 144. Flavored Rum 304. Flavored Cognac 150. Rhum Agricole 310. Armagnac 151. Guaro and Aguardiente 320. Calvados 152. Cachaça 330. Apple Brandy 153. Other Sugar Cane Based Spirits 340. Alambic Brandy 160. Silver/Gold (Unaged) Tequila 350. French Grape Brandy 161. Reposado Tequila 360. American Grape Brandy 162. Añejo Tequila 370. Spanish Grape Brandy & Brandy de Jerez 163 Extra Añejo 380. Italian Grape Brandy 170. Mixto Tequila 171. Flavored Tequila 390. Other Brandy 172. Mezcal 400. -

The National Parks of Costa Rica

The National Parks Of Costa Rica Exploring the most biodiverse country on earth The National Parks Of Costa Rica The National Parks Of Costa Rica: Exploring the most biodiverse country on earth Exploring the most biodiverse country on earth Copyright © 2016 Horizon Guides Presented by: All our coverage is 100% impartial and editorially independent. Our guides are researched and written by destination experts and are not influenced in any way by our sponsors. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of all advice provided in this guide, the reality is that any travel information is liable to change at short notice. We strongly advise that you verify any important details prior to your trip as we cannot be held responsible for errors or information that has since become outdated. Published by Horizon Guides Suite 38, Alison Business Centre 39-40 Alison Crescent, Sheffield, S2 1AS http://horizontravelpress.com/ Edited by Cynthia Ord Layout & design by Simon Ross-Gill Front cover photograph: Brandon Alms © 123RF.com Contents Using This Guide 6 Welcome to Costa Rica Adventure Without End 10 Highlights 12 About The Authors 15 Best For... Best For Nature And Birdwatching 18 Best For Beach Escapes 21 Best For Active Adventures 22 Best For Families And Kids 25 Best For Luxurious Retreats 26 Exploring Costa Rica Costa Rica's National Parks, At A Glance 30 A A C C I Manuel Antonio National Park 32 I R R A A Poás Volcano National Park 36 A T T Tortuguero National Park 40 F COS F Cahuita National Park 45 COS F O Arenal Volcano National