Conference Reader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Viimeinen Päivitys 8

Versio 20.10.2012 (222 siv.). HÖYRY-, TEOLLISUUS- JA LIIKENNEHISTORIAA MAAILMALLA. INDUSTRIAL AND TRANSPORTATION HERITAGE IN THE WORLD. (http://www.steamengine.fi/) Suomen Höyrykoneyhdistys ry. The Steam Engine Society of Finland. © Erkki Härö [email protected] Sisältöryhmitys: Index: 1.A. Höyry-yhdistykset, verkostot. Societies, Associations, Networks related to the Steam Heritage. 1.B. Höyrymuseot. Steam Museums. 2. Teollisuusperinneyhdistykset ja verkostot. Industrial Heritage Associations and Networks. 3. Laajat teollisuusmuseot, tiedekeskukset. Main Industrial Museums, Science Centres. 4. Energiantuotanto, voimalat. Energy, Power Stations. 5.A. Paperi ja pahvi. Yhdistykset ja verkostot. Paper and Cardboard History. Associations and Networks. 5.B. Paperi ja pahvi. Museot. Paper and Cardboard. Museums. 6. Puusepänteollisuus, sahat ja uitto jne. Sawmills, Timber Floating, Woodworking, Carpentry etc. 7.A. Metalliruukit, metalliteollisuus. Yhdistykset ja verkostot. Ironworks, Metallurgy. Associations and Networks. 7.B. Ruukki- ja metalliteollisuusmuseot. Ironworks, Metallurgy. Museums. 1 8. Konepajateollisuus, koneet. Yhdistykset ja museot. Mechanical Works, Machinery. Associations and Museums. 9.A. Kaivokset ja louhokset (metallit, savi, kivi, kalkki). Yhdistykset ja verkostot. Mining, Quarrying, Peat etc. Associations and Networks. 9.B. Kaivosmuseot. Mining Museums. 10. Tiiliteollisuus. Brick Industry. 11. Lasiteollisuus, keramiikka. Glass, Clayware etc. 12.A. Tekstiiliteollisuus, nahka. Verkostot. Textile Industry, Leather. Networks. -

UNE MINE DE Découvertes 25 Élèves

Le Bois du Cazier incontournable pour Nos offres combinées : 1956-2021 vos sorties scolaires ! Combinez une visite parmi notre offre et la LE BOIS Groupes découverte d’un autre lieu partenaire pour 2020 e une journée thématique : DU CAZIER 65 > Un site chargé d’histoire classé au Patrimoine scolaires ANNIVERSAIRE mondial de l’Unesco et labellisé par l’Union DE LA TRAGÉDIE NIO M O UN IM D ~ R T IA A L • P • W Le Bois du CazieR L O A I R D + L D N O Secondaires Européenne H E M R I E TA IN G O E • PATRIM Organisation Sites miniers majeurs > Un lieu proche de chez vous à un tarif des Nations Unies de Wallonie pour l’éducation, inscrits sur la Liste du et extrascolaires la science et la culture patrimoine mondial en 2012 2021 intéressant Un des Sites miniers dès (12-18 ans) > Accessible en car et transports en commun majeurs de Wallonie 12€ > Espace pique-nique disponible sur réservation (Grand-Hornu, Bois-du-Luc ou Blegny-Mine) THUIN, son beffroi Tarifs et ses bateliers 10€ Entrée : 3.5€ / élève - Visite guidée : 60€ / groupe de max. UNE MINE DE DÉCOUVERTEs 25 élèves. Sambre et charbonnages 11€ Possibilité d’accueillir plusieurs groupes simultanément. Un accompagnateur gratuit par groupe de 25 élèves. Musée du Verre : + 30€ (secondaire) Abbaye d’Aulne 12€ Couleur > visites En lien avec les Réservation indispensable Chocolat 11,50€ Par téléphone : 071/29 89 30 programmes scolaires Par email : [email protected] Maison de la Poterie 6.50€ > thématiques citoyennes Pour vos classes de dépaysement Musée royal Séjournez dans un des hébergements proches du site et bé- de Mariemont 13€ néficiez d’un tarif préférentiel sur votre visite :Auberges de > Une journée entière sur le Jeunesse de Charleroi, Mons et Namur ; Centre Marcel Tricot à Beaumont ; Centre Adeps de Loverval et Centre de Dépay- Mundaneum 10€ site pour 8,30 € / élève* sement et de Plein Air de Sivry. -

Un Des 4 Sites Miniers Majeurs De Wallonie NEWS Bulletin D’Information De Blegny-Mine Asbl / N°39 Août 2018 De Blegny-Mine Bulletin D’Information

Un des 4 sites miniers majeurs de Wallonie NEWS Bulletin d’information de Blegny-Mine asbl / n°39 Août 2018 de Blegny-Mine Bulletin d’information Sommaire 2 à 3 : La vie en réseau 4 à 6 : Sites Unesco 7 : Le saviez-vous ? 8 à 11 : Nous étions présents 11 : In memoriam 12 : Quoi de neuf ? 13 à 14 : Face aux médias 14 : Personnel 15 : Dons/Acquisitions 16 : Ils nous ont rendu visite 17 à 19 : Au fil des jours 20 : Agenda La Fosse 9-9 bis d’Oignies Rue L. Marlet, 23 - 4670 BLEGNY - Tel. : 04/387 43 33 - Fax : 04/387 58 50 www.blegnymine.be - [email protected] Edito Une institution culturelle comme La vie en réseau la nôtre peut difficilement vivre seule, sans échange avec d’autres institutions similaires ou avec des associations fé- Afin de structurer quelque peu cet article, j’ai classé les réseaux dont fait partie Blegny-Mine en thématiques : les sponsors principaux, les dératrices ou qui poursuivent des buts réseaux touristiques, culturels et professionnels, la vie locale, et le identiques. Ces échanges, qui font partie patrimoine industriel, à la fois sur le plan régional et international. des obligations contractées vis-à-vis de l’Unesco dans le cadre de notre recon- 1) Les sponsors principaux : naissance comme patrimoine mondial, sont à la fois sources d’amélioration des Les trois sponsors principaux de Blegny-Mine sont la Région wal- connaissances et de l’expérience, de créa- lonne, à travers le Commissariat Général au Tourisme (CGT) et le tion d’un réseau relationnel bien utile Forem, la Province de Liège via sa Fédération du Tourisme (FTPL), et la commune de Blegny. -

PROGRAMMES Groupes Adultes 2020/21 Associations, Amicales, Services-Clubs, Groupes D’Amis,

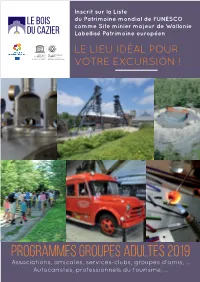

Inscrit sur la Liste LE BOIS du Patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO comme Site minier majeur de Wallonie DU CAZIER Labellisé Patrimoine européen NIO M O UN IM D R T IA A L • P • W L O A I R D L D N H O E M R I E TA IN G O E • PATRIM LE LIEU IDÉAL POUR Organisation Sites miniers majeurs des Nations Unies de Wallonie pour l’éducation, inscrits sur la Liste du la science et la culture patrimoine mondial en 2012 VOTRE EXCURSION ! PROGRAMMES groupes adultes 2020/21 Associations, amicales, services-clubs, groupes d’amis, ... Autocaristes, professionnels du tourisme, … POURQUOI UNE VISITE DU SITE DU BOIS DU CAZIER ? Partie du Patrimoine exceptionnel de Wallonie, inscrit sur la liste du Patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO avec trois autres sites miniers majeurs, labellisé Patrimoine européen par l’UE, le Bois du Cazier, requalifié en musée et en attraction touristique, connait une destinée assez exceptionnelle. Le Bois du Cazier est un site minier mais il est plus qu’un musée de la mine, il est un témoignage du passé industriel de la Wallonie. Selon la formule « le passé, présent pour le futur », un parcours muséal consacré au charbon, au fer et au verre, fait du Bois du Cazier une vitrine du savoir-faire humain, de ses réussites mais aussi de ses dérives… Le Bois du Cazier rend hommage aux hommes, ouvriers et ingénieurs, qui hissèrent la Belgique dans le concert des plus grandes nations industrielles. Il est ainsi devenu un lieu de référence dans le domaine du patrimoine industriel et un site culturel et touristique majeur. -

Patrimoine Et Territoire Comment Le Patrimoine Peut Être Un Moteur D’Évolution Du Territoire ?

HORS LES DOSSIERS SÉRIE DE L’IPW Patrimoine et territoire Comment le patrimoine peut être un moteur d’évolution du territoire ? Actes du colloque transfrontalier des 25 et 26 septembre 2014 Caroline PINON (coord.) Patrimoine et territoire - Comment le patrimoine peut être un moteur d’évolution du ? Institut du Patrimoine wallon Patrimoine et territoire Comment le patrimoine peut être un moteur d’évolution du territoire ? LES DOSSIERS DE l’IPW, Hors série Patrimoine et territoire Comment le patrimoine peut être un moteur d’évolution du territoire ? Actes du colloque transfrontalier des 25 et 26 septembre 2014 Station touristique du ValJoly – Eppe-Sauvage (France) Caroline PINON (coord.) Édition Institut du Patrimoine wallon (IPW) Rue du Lombard, 79 B-5000 Namur Éditeur responsable Freddy JORIS Suivi éditorial Sandrine LANGOHR et Julien MAQUET (IPW) Informations concernant la vente des publications de l’IPW Service « Publications » Tél. : +32 (0)81 230 703 ou +32 (0)81 654 154 Fax : +32 (0)81 231 890 E-mail : [email protected] Graphisme de la couverture Douple Page, Liège Mise en page et impression Imprimerie Snel, Vottem Couverture Eppe – Sauvage © C. ROUVRES – CAUE du Nord 4e de couverture Moulin © BINARIO architecture Mur en pierres sèches © I. BOXUS – IPW Vue aérienne de Gravelines © CHEUVA Le texte engage la seule responsabilité des auteurs. L’éditeur s’est efforcé de régler les droits relatifs aux illustra - tions conformément aux prescriptions légales. Les détenteurs de droits que, malgré nos recherches, nous n’aurions pas pu retrouver sont priés de se faire connaître à l’éditeur. Tous droits réservés pour tous pays ISBN : 978-2-87522-146-9 Dépôt légal : D/2014/10.015/26 Table des matières Préface. -

National Reports 2016 - 2018

CONGRESSO XVII - CHILE NATIONAL REPORTS 2016 - 2018 EDITED BY JAMES DOUET TICCIH National Reports 2016-2018 National Reports on Industrial Heritage Presented on the Occasion of the XVII International TICCIH Congress Santiago de Chile, Chile Industrial Heritage: Understanding the Past, Making the Future Sustainable 13 and 14 September 2018 Edited by James Douet THE INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE FOR THE CONSERVATION OF INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE TICCIH Congress 2018 National Reports The International Committee for the Conservation of the Indus- trial Heritage is the world organization for industrial heritage. Its goals are to promote international cooperation in preserving, conserving, investigating, documenting, researching, interpreting, and advancing education of the industrial heritage. Editor: James Douet, TICCIH Bulletin editor: [email protected] TICCIH President: Professor Patrick Martin, Professor of Archae- ology Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI 49931, USA: [email protected] Secretary: Stephen Hughes: [email protected] Congress Director: Jaime Migone Rettig [email protected] http://ticcih.org/ Design and layout: Daniel Schneider, Distributed free to members and congress participants September 2018 Opinions expressed are the authors’ and do not necessarily re- flect those of TICCIH. Photographs are by the authors unless stated otherwise. The copyright of all pictures and drawings in this book belongs to the authors. No part of this publication may be reproduced for any other purposes without authorization or permission -

The Overview of the Conservation and Renewal of the Industrial Belgian Heritage As a Vector for Cultural Regeneration

information Review The Overview of the Conservation and Renewal of the Industrial Belgian Heritage as a Vector for Cultural Regeneration Jiazhen Zhang 1, Jeremy Cenci 1,* , Vincent Becue 1 and Sesil Koutra 1,2 1 Faculty of Architecture and Urban Planning, University of Mons, Rue d’ Havre, 88, 7000 Mons, Belgium; [email protected] (J.Z.); [email protected] (V.B.); [email protected] (S.K.) 2 Faculty of Engineering, Erasmus Mundus Joint Master SMACCs, University of Mons, 7000 Mons, Belgium * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-498-79-1173 Abstract: Industrial heritage reflects the development track of human production activities and witnessed the rise and fall of industrial civilization. As one of the earliest countries in the world to start the Industrial Revolution, Belgium has a rich industrial history. Over the past years, a set of industrial heritage renewal projects have emerged in Belgium in the process of urban regeneration. In this paper, we introduce the basic contents of the related terms of industrial heritage, examine the overall situation of protection and renewal in Belgium. The industrial heritage in Belgium shows its regional characteristics, each region has its representative industrial heritage types. In the Walloon region, it is the heavy industry. In Flanders, it is the textile industry. In Brussels, it is the service industry. The kinds of industrial heritages in Belgium are coordinate with each other. Industrial heritage tourism is developed, especially on eco-tourism, experience tourism. The industrial heritage in transportation and mining are the representative industrial heritages in Belgium. -

Mining Sites of Wallonia (Belgium) No 1344Rev

a) Clarify the ownership situation of Blegny-Mine and contractualize responsibility for its Mining Sites of Wallonia management with the management company; (Belgium) b) Review the buffer zone at Bois-du-Luc, in accordance with the principles already applied No 1344rev to the buffer zones for the three other sites; c) Make in-depth protection of the property’s components effective through systematic inclusion on the list of historic monuments and protected cultural sites in Wallonia. The Official name as proposed by the State Party protection must be coordinated between the The Major Mining Sites of Wallonia various sites and it should achieve the highest level possible; Location d) Formalize and promulgate a harmonized Communes of Boussu, La Louvière, Charleroi, Blegny protection system for the buffer zones in direct Provinces of Hainaut and Liège relationship with the property’s Outstanding Walloon Region Universal Value, and take into account the need Belgium to protect the surroundings of the property’s components, especially through control of urban Brief description development; The Grand-Hornu, Bois-du-Luc, Bois du Cazier, and e) Create a conservation plan for the entire Blegny-Mine sites are the best preserved coal-mining sites th property, defining its methodology and in Belgium, dating from the early 19 century to the th monitoring and specifying its managers and second half of the 20 century. They are testimony to stakeholders. This plan should, in particular, surface and underground mining, the industrial take into account the restoration of the architecture associated with the mines, worker housing, conditions of authenticity of the private houses mining town planning, and the social and human values of on the Grand-Hornu estate; their history, especially the Bois du Cazier disaster (1956). -

Mise En Page Dernière Version.Indd

Inscrit sur la Liste LE BOIS du Patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO comme Site minier majeur de Wallonie DU CAZIER Labellisé Patrimoine européen NIO M O UN IM D R T IA A L • P • W L O A I R D L D N H O E M R I E TA IN G O E • PATRIM LE LIEU IDÉAL POUR Organisation Sites miniers majeurs des Nations Unies de Wallonie pour l’éducation, inscrits sur la Liste du la science et la culture patrimoine mondial en 2012 VOTRE EXCURSION ! PROGRAMMES groupes adultes 2019 Associations, amicales, services-clubs, groupes d’amis, ... Autocaristes, professionnels du tourisme, … POURQUOI UNE VISITE DU SITE DU BOIS DU CAZIER ? Partie du Patrimoine exceptionnel de Wallonie, inscrit sur la liste du Patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO avec trois autres sites miniers majeurs, labellisé Patrimoine européen par l’UE, le Bois du Cazier, requalifié en musée et en attraction touristique, connait une destinée assez exceptionnelle. Le Bois du Cazier est un site minier mais il est plus qu’un musée de la mine, il est un témoignage du passé industriel de la Wallonie. Selon la formule « le passé, présent pour le futur », un parcours muséal consacré au charbon, au fer et au verre, fait du Bois du Cazier une vitrine du savoir-faire humain, de ses réussites mais aussi de ses dérives… Le Bois du Cazier rend hommage aux hommes, ouvriers et ingé- nieurs, qui hissèrent la Belgique dans le concert des plus grandes nations industrielles. Il est ainsi devenu un lieu de référence dans le domaine du patrimoine industriel et un site culturel et touristique majeur. -

TICCIH XV Congress 2012

TICCIH Congress 2012 The International Conservation for the Industrial Heritage Series 2 Selected Papers of the XVth International Congress of the International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage § SECTION II: PLANNING AND DESIGN 113 A Study of the Hydraulic Landscape in Taoyuan Tableland: the Past, Present and Future / CHEN, Chie-Peng 114 A Study on Preservation, Restoration and Reuse of the Industrial Heritage in Taiwan: The Case of Taichung Creative Cultural Park / YANG, Hong-Siang 138 A Study of Tianjin Binhai New Area’s Industrial Heritage / YAN, Mi 153 Selective Interpretation of Chinese Industrial Heritage Case study of Shenyang Tiexi District / FAN, Xiaojun 161 Economization or Heritagization of Industrial Remains? Coupling of Conservation and CONTENTS Urban Regeneration in Incheon, South Korea / CHO, Mihye 169 Preservation and Reuse of Industrial Heritage along the Banks of the Huangpu River in Shanghai / YU, Yi-Fan 180 Industrial Heritage and Urban Regeneration in Italy: the Formation of New Urban Landscapes / PREITE, Massimo 189 Rethinking the “Reuse” of Industrial Heritage in Shanghai with the Comparison of Industrial Heritage in Italy / TRISCIUOGLIO, Marco 200 § SECTION III: INTERPRETATION AND APPLICATION 207 The Japanese Colonial Empire and its Industrial Legacy / Stuart B. SMITH 208 FOREWORDS 1 “La Dificultad” Mine. A Site Museum and Interpretation Center in the Mining District of FOREWORD ∕ MARTIN, Patrick 2 Real del Monte and Pachuca / OVIEDO GAMEZ, Belem 219 FOREWORD ∕ LIN, Hsiao-Wei 3 Tracing -

Les Cahiers Du Tourisme Tourisme Et Sites Reconvertis

Les Cahiers du Tourisme Tourisme et sites reconvertis Commissariat général au Tourisme Juillet 2011 2011 JUILLET | N°3 Commissariat général au Tourisme | Les Cahiers du Tourisme Tourisme et sites reconvertis | Commissariat général au Tourisme N°3 | Juillet 2011 http://strategie.tourismewallonie.be Les Cahiers du Tourisme 3 2 51 N°Tourisme et3 sites reconvertis Table des matières Éditorial (M. J.-P. Lambot) 4 La valorisation touristique du patrimoine bâti (M. F. Joris) 5 La volonté est forte en Wallonie de mettre en valeur son patrimoine architectural, composante majeure de l’image régionale et moteur de développement touristique. Les synergies “patrimoine”, “tourisme” et aussi “culture” se multiplient pour répondre au mieux aux attentes du public tout en préservant les richesses du bâti, qui n’aurait parfois pas pu l’être sans le tourisme. Patrimoine, Urban Resort, Crowne Plaza : un concept audacieux pour un cadre prestigieux. (M. N. Seggaï) 9 Le prestigieux “Crowne Plaza Liège”, 2e hôtel 5 étoiles de Wallonie, vient d’ouvrir ses portes. Cet “Urban Resort” haut de gamme fait revivre les deux Hôtels des Comtes de Méan et de Sélys-Longchamps (“bien exceptionnel”) datant du XVIe siècle. Opportunité économique pour la Cité Ardente et beau projet de revalorisation patrimoniale. Pas de mémoires sans touristes ? Pour une lecture politique des relations entre mémoires et tourisme (M. O. Lazarotti) 13 La reconnaissance mémorielle stimule indéniablement la fréquentation touristique et, à l’inverse, il n’y aurait dans certains cas pas de mémoires sans touristes. Analyse de la relation mémoire-tourisme, ses atouts et ses limites. L’aménagement d’un hôtel-restaurant dans le Château Fort de Sedan ou la construction de la réussite d’un véritable partenariat public-privé (M. -

Bulletin 21 – Summer 2003

BULLETIN No. 21 ● Summer 2003 Getting a good deal of money (€90 million, mainly from EU Opinion sources), the newly established ‘EGZ’ (Zollverein Develop- ment Corporation) put forward a plan to make Zollverein an Rheinisches Amt für Denkmalpfege international centre of design, incorporating a design school and a worldwide, 100-day fair, called ‘metaform’ that is to Axel Föhl take place in 2005 for the frst time (every fve years hence). At the moment the debate is about how to transform the highly In December 2001, the 1930’s complex of hard coal mine intact coal washing plant, that is densely packed with his- and coking plant (1958-1987) of Zollverein in Essen-Kater- toric machinery, into a ‘plug-in centre’ as well as into a newly nberg in the Western part of the Ruhrgebiet was declared a planned ‘Ruhrmuseum’. Here again the question is whether World Heritage Site. It is the third large-scale industrial com- someone like Rotterdam architect Rem Koolhaas, who has plex to be part of the German list. Rammelsberg metal ore designed buildings like the famous The Hague ‘Netherlands mine (including the mediaeval centre of nearby Goslar) and Dance Theatre’, is the most suitable architect to carefully Völklingen blast furnace works preceded Zollverein in 1992 blend historic structures with new uses, cautiously discern- and respectively 1994. There is no question that the all-round ing between using something in a diferent way or using it up. qualities of the 120 hectare Zollverein site make it an out- One has to keep in mind that Zollverein XII was made a World standing monument to the history of technology as well as Heritage Site for what it is and not for what it could possibly to the architectural history of the 20th century.