Australian Fisheries and Aquaculture Statistics 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES and RESPONSIBLE AQUACULTURE: a Guide for USAID Staff and Partners

SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES AND RESPONSIBLE AQUACULTURE: A Guide for USAID Staff and Partners June 2013 ABOUT THIS GUIDE GOAL This guide provides basic information on how to design programs to reform capture fisheries (also referred to as “wild” fisheries) and aquaculture sectors to ensure sound and effective development, environmental sustainability, economic profitability, and social responsibility. To achieve these objectives, this document focuses on ways to reduce the threats to biodiversity and ecosystem productivity through improved governance and more integrated planning and management practices. In the face of food insecurity, global climate change, and increasing population pressures, it is imperative that development programs help to maintain ecosystem resilience and the multiple goods and services that ecosystems provide. Conserving biodiversity and ecosystem functions are central to maintaining ecosystem integrity, health, and productivity. The intent of the guide is not to suggest that fisheries and aquaculture are interchangeable: these sectors are unique although linked. The world cannot afford to neglect global fisheries and expect aquaculture to fill that void. Global food security will not be achievable without reversing the decline of fisheries, restoring fisheries productivity, and moving towards more environmentally friendly and responsible aquaculture. There is a need for reform in both fisheries and aquaculture to reduce their environmental and social impacts. USAID’s experience has shown that well-designed programs can reform capture fisheries management, reducing threats to biodiversity while leading to increased productivity, incomes, and livelihoods. Agency programs have focused on an ecosystem-based approach to management in conjunction with improved governance, secure tenure and access to resources, and the application of modern management practices. -

Recirculating Aquaculture Tank Production Systems: Aquaponics—Integrating Fish and Plant Culture

SRAC Publication No. 454 November 2006 VI Revision PR Recirculating Aquaculture Tank Production Systems: Aquaponics—Integrating Fish and Plant Culture James E. Rakocy1, Michael P. Masser2 and Thomas M. Losordo3 Aquaponics, the combined culture of many times, non-toxic nutrients and Aquaponic systems offer several ben- fish and plants in recirculating sys- organic matter accumulate. These efits. Dissolved waste nutrients are tems, has become increasingly popu- metabolic by-products need not be recovered by the plants, reducing dis- lar. Now a news group (aquaponics- wasted if they are channeled into charge to the environment and [email protected] — type sub- secondary crops that have economic extending water use (i.e., by remov- scribe) on the Internet discusses value or in some way benefit the pri- ing dissolved nutrients through plant many aspects of aquaponics on a mary fish production system. uptake, the water exchange rate can daily basis. Since 1997, a quarterly Systems that grow additional crops be reduced). Minimizing water periodical (Aquaponics Journal) has by utilizing by-products from the pro- exchange reduces the costs of operat- published informative articles, con- duction of the primary species are ing aquaponic systems in arid cli- ference announcements and product referred to as integrated systems. If mates and heated greenhouses where advertisements. At least two large the secondary crops are aquatic or water or heated water is a significant suppliers of aquaculture and/or terrestrial plants grown in conjunc- expense. Having a secondary plant hydroponic equipment have intro- tion with fish, this integrated system crop that receives most of its required duced aquaponic systems to their is referred to as an aquaponic system catalogs. -

Overview of the Potential Interactions and Impacts of Commercial Fishing Methods on Marine Habitats and Species Protected Under the Eu Habitats Directive

THE N2K GROUP European Economic Interest Group OVERVIEW OF THE POTENTIAL INTERACTIONS AND IMPACTS OF COMMERCIAL FISHING METHODS ON MARINE HABITATS AND SPECIES PROTECTED UNDER THE EU HABITATS DIRECTIVE Contents GLOSSARY................................................................................................................................................3 1. BACKGROUND.................................................................................................................................6 1.1 Fisheries interactions ....................................................................................................................7 2. FISHERIES AND NATURA 2000 - PRESSURES, INTERACTIONS, AND IMPACTS ....................................8 2.1 POTENTIAL PHYSICAL, CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL PRESSURES AND IMPACTS ASSOCIATED WITH COMMERCIAL FISHING METHODS ............................................................................................8 DREDGES .......................................................................................................................................11 TRAWL - PELAGIC ..........................................................................................................................12 HOOK & LINE.................................................................................................................................12 TRAPS ............................................................................................................................................12 NETS ..............................................................................................................................................13 -

Pottawatomie County Is Home to Aquaponics Farm

Pottawatomie County is home to aquaponics farm By Donna Sullivan, Editor Once the fry are hatched, What began as an effort Sperman uses a net to scoop to ensure his diabetic father a them into a bucket to trans- reliable protein supply if port to fry pools. The bread availability to his medication and butter of his business is were interrupted has grown selling three-quarter to one- into a growing business ven- inch fry in bulk. “When fry ture for Pottawatomie Coun- are the size of mosquito lar- ty resident James Sperman. vae, they’re not the most re- Travelers along Highway 24 silient things in the world,” between Manhattan and he said. So he waits about Wamego may have noticed two weeks for them to grow the high tunnel, semi-pit to around an inch, then ships greenhouse and large blue them nationwide. “None of pools that house his my fish go to waste,” he con- aquaponic gardening system tinued. “The ones that I and tilapia farm. don’t manage to find homes Aquaponics combines for can grow and become fish farming with hydropon- adolescents and some are ic gardening inside a high just on the verge of becom- tunnel, which allows for the ing breeders and will be- production of fruits, vegeta- come pond stockers.” bles and fish year-round. The Sperman says that be- system has a 1,700-gallon cause tilapia are predomi- fish tank and 165-square- nantly vegetarian and are fil- foot grow bed. Water from ter feeders, the algae and the fish tank carries fish bacteria that grows in the waste to the grow bed, where James Sperman describes how he feeds the fish at only one end of the pond since the females release their eggs pools is tailored perfectly to it feeds the plants. -

FISHING NEWSLETTER 2020/2021 Table of Contents FWP Administrative Regions and Hatchery Locations

FISHING NEWSLETTER 2020/2021 Table of Contents FWP Administrative Regions and Hatchery Locations .........................................................................................3 Region 1 Reports: Northwest Montana ..........................................................................................................5 Region 2 Reports: West Central Montana .....................................................................................................17 Region 3 Reports: Southwest Montana ........................................................................................................34 Region 4 Reports: North Central Montana ...................................................................................................44 Region 5 Reports: South Central Montana ...................................................................................................65 Region 6 Reports: Northeast Montana ........................................................................................................73 Region 7 Reports: Southeast Montana .........................................................................................................86 Montana Fish Hatchery Reports: .......................................................................................................................92 Murray Springs Trout Hatchery ...................................................................................................................92 Washoe Park Trout Hatchery .......................................................................................................................93 -

Preparing Trolling Lines

CHAPTER 3 PREPARING TROLLING LINES A. TOOLS AND UTENSILS B. HOOKS -Hook types -Sharpening hooks -Ganging hooks C. 'TYPES OF FISHING LINE -Handling lines -Line characteristics D. END LOOPS IN LINE AND SINGLE-STRAND WIRE -Double figure-eight knot -Using end loops -End loops in wire E. .END LOOPS IN ROPE -Whipping and sealing rope ends -Bowline knot -Eye splice F. END LOOPS IN CABLE (MULTI-STRAND WIRE) -Wrapped end loops -Flemish eye -Crimping cable -Lazy splice G. KNOTS FOR HOOKS AND TACKLE -Palomar knot -Slip knot -Clinch knot -'Trilene' knot -Tying a hook rigid on wire H. JOINING LINES TOGETHER -Blood knot (Barrel knot) -Double slip knot -Using end loops -Connector rings and swivels I. THE ASSEMBLED TROLLING LINE -The mainline -The trace -Changing traces- Trace length -The backing J. SINKERS -Heavier line materials -Sinkers -Downriggers -Cannonballs K. DIVING DEVICES -Diving boards -Tripping -Diving lures -Trolling depth L. RIGGING FIXED LINES -Making shock absorbers -Rigging shock absorbers -Position -Backing cord and lazy line -Line storage M. RIGGING LINES ON HAND REELS -Loading the reel -Overloading -Adjustments -Using wire N. RIGGING HANDREELS FOR TROLLING -Rigging through a trolling boom -Rabbit line -Boom stays -Braking system (drag) -Lazy line 29 CHAPTER 3: PREPARING TROLLING LINES SECTION A: TOOLS AND UTENSILS Most of the preparation for trolling is normally done on shore before the fishing trip starts. This makes gear rigging easier and more comfortable, prevents new materials being contaminated with salt water before they are used, and avoids wasting time at sea which could better be used in fishing or carrying out other tasks on the boat. -

Fishery Basics – Fishing Vessels Fishing Vessel Types

Fishery Basics – Fishing Vessels Fishing Vessel Types Fishing vessels are typically designed with a specific purpose. That purpose is to locate, catch, and preserve fish while out at sea. The planned operations of a vessel determine the overall size of the vessel, the arrangement of the deck, carrying capacity, as well as the machinery and types of equipment that will be supported by the vessel. Due to the inherent differences in fishing communities around the world, there is a wide range of types and styles of fishing vessels. Vessel sizes can range from the 2 m (6 ft) dug out canoes used in subsistence and artisanal fisheries, to factory ships that exceed 130 m (427 ft) in length. Commercial fishing vessels can also be characterized by a variety of criteria: types of fish (See Biology & Ecology) they catch, fishing gear and methods used (See Fishing Gear), capacity and processing capabilities, and the geographical origin of the vessel. In 2002, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimated the world fishing fleet had approximately four million vessels, with an average vessel size ranging from 10-15 m (33-49 ft). Based on a quarterly catch statistics report, published by the Pacific Fisheries Information Network (PacFIN), approximately 1,950 vessels landed their catches in California ports. Due to the technological innovations that began in the 1950s, many fishing vessels are now classified as multi-purpose vessels, because of the ability to switch out gear types depending on the targeted species. However, single use vessels still exist in the world fishing fleet today. -

A Strategic Approach to Sustainable Shrimp Production in Thailand

A Strategic Approach to Sustainable Shrimp Production in Thailand THE CASE FOR IMPROVED ECONOMICS AND SUSTAINABILITY Boston Consulting Group partners with leaders in business and society to tackle their most important challenges and capture their greatest opportunities. BCG was the pioneer in business strategy when it was founded in 1963. Today, we help clients with total transformation—inspiring complex change, enabling organizations to grow, building competitive advantage, and driving bottom-line impact. To succeed, organizations must blend digital and human capabilities. Our diverse, global teams bring deep industry and functional expertise and a range of perspectives to spark change. BCG delivers solutions through leading-edge management consulting along with technology and design, corporate and digital ventures—and business purpose. We work in a uniquely collaborative model across the firm and throughout all levels of the client organization, generating results that allow our clients to thrive. A STRATEGIC APPROACH TO SUSTAINABLE SHRIMP PRODUCTION IN THAILAND THE CASE FOR IMPROVED ECONOMICS AND SUSTAINABILITY HOLGER RUBEL WENDY WOODS DAVID PÉREZ SHALINI UNNIKRISHNAN ALEXANDER MEYER ZUM FELDE SOPHIE ZIELCKE CHARLOTTE LIDY CAROLIN LANFER July 2019 | Boston Consulting Group CONTENTS 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 MARKET FORCES ARE RESHAPING THE GLOBAL SHRIMP INDUSTRY 8 THE THAI SHRIMP INDUSTRY IS AT AN INFLECTION POINT The Perfect Storm Has Hit Thai Shrimp Production in Recent Years Thailand Is Weathering the Storm but Is Still Losing Ground -

Genetic and Demographic Implications of Aquaculture in White Sturgeon (Acipenser Transmontanus) Conservation

1733 Genetic and demographic implications of aquaculture in white sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus) conservation Henriette I. Jager Abstract: This study uses a genetic individual-based model of white sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus) populations in a river to examine the genetic and demographic trade-offs associated with operating a conservation hatchery. Simula- tion experiments evaluated three management practices: (i) setting quotas to equalize family contributions in an effort to prevent genetic swamping, (ii) an adaptive management scheme that interrupts stocking when introgression exceeds a specified threshold, and (iii) alternative broodstock selection strategies that influence domestication. The first set of simulations, designed to evaluate equalizing the genetic contribution of families, did not show the genetic benefits expected. The second set of simulations showed that simulated adaptive management was not successful in controlling introgression over the long term, especially with uncertain feedback. The third set of simulations compared the effects of three alternative broodstock selection strategies on domestication for hypothetical traits controlling early density-dependent survival. Simulated aquaculture selected for a density-tolerant phenotype when broodstock were taken from a genetically connected population. Using broodstock from an isolated population (i.e., above an upstream barrier or in a different watershed) was more effective at preventing domestication than using wild broodstock from a connected population. -

Business Plan to Support the Improvement of the Yellowfin Tuna (Thunnus Albacares) Small-Scale Fishery in the Galapagos Marine Reserve, Ecuador

Business plan to support the improvement of the yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) small-scale fishery in the Galapagos Marine Reserve, Ecuador Developed as part of the GEF-funded, World Bank-implemented Ocean Partnerships for Sustainable Fisheries and Biodiversity Conservation (OPP), a sub-project of the Common Oceans ABNJ Program led by UN-FAO Fishery location: Galapagos Islands, Ecuador Report authors: Viteri, C., Obregón, P., Castrejón, M., and Yoshioka, J. Organization: Conservation International Report date: December 2018 1 Version Control Amendments Issued Version No. Date Description of Amendment 1.0 October 23 2018 First draft 2.0 December 31 2018 Second draft The current materials drafted by Conservation International are a product of the GEF-funded, World Bank- implemented project titled 'Ocean Partnership for Sustainable Fisheries and Biodiversity Conservation (OPP)', and is part of the FAO Common Oceans Program. The opinions expressed in this report belong solely to the authors, and are not necessarily endorsed by reviewers, by the GEF or by the World Bank". This document is to be cited as: Viteri, C., Obregón, P., Castrejón, M., and Yoshioka, J. 2018. Business plan to support the improvement of the yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) small-scale fishery in the Galapagos Marine Reserve, Ecuador. Conservation International. 72 pp. Acknowledgements: The authors want to thank Scott Henderson, Jack Kittinger, Luis Suarez, Jerson Moreno, Mariana Vera, and the Galapagos National Park staff, particularly Harry Reyes and Danny Rueda for their support in the development of the Galapagos Tuna Business Case. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Investment overview 5 1. INTRODUCTION 10 2. CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS 16 2.1 Overview and Background of The Galapagos Islands 16 2.2 Governance and management of the Galapagos Marine Reserve 17 2.3 The yellowfin tuna fishery 19 2.3.1 Stock status 21 2.3.2 Governance and management of the Galapagos tuna fishery 23 2.3.3 organization and entrepreneurial capacity of the small-scale fishing sector: 25 3. -

The New Fisherman

WILLIAM B. McCLOSKEY, JR. THE NEW FISHERMAN Hydraulic hoses and black boxes make fishing easier, but exact a price. We took hail and spray in our faces and crouched buoy of the first crab pot: barely a minute's search monkey-style to keep pace while working the gear on for a 2-foot pink buoy hidden in rolling seas during a a pitching deck glazed with ice. The wind blew a snowstom. straight 35 knots and gusted 60. Up through the Despite the weather, we worked all night, black hydraulic block zipped a crab pot-a 7-foot-square waves that could obliterate us towering over our by 3-foot steel-framed cage. Seven hundred pounds deck; worked without stop through all the daylight empty, it would now weigh 1000 to 2500 pou~ hours and on through the next night until about 2 depending on the number of king crabs insi£ Its AM. At last, peeling off our raingear but nothing else, trip up from the seafloor 60 fathoms below took we groaned to our bunks. about a minute. The pot surfaced in a froth of purple By the first grey light, the skipper had the wheel crab shapes and water. We braced it at the rail again. He slowed the engine, a standard signal. Our waiting for the proper boat motion, and swung it fishermen's discipline responded with feet back into aboard, holding tight to prevent a wild swing. Then it damp boots, salt-clammy raingear over our clothes. was teamwork on the run, to prepare the line and And so for seven days, until our tanks were filled. -

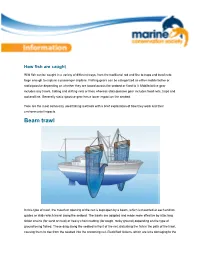

How Fish Are Caught

How fish are caught Wild fish can be caught in a variety of different ways, from the traditional rod and line to traps and trawl nets large enough to capture a passenger airplane. Fishing gears can be categorized as either mobile/active or static/passive depending on whether they are towed across the seabed or fixed to it. Mobile/active gear includes any trawls, trolling and drifting nets or lines whereas static/passive gear includes fixed nets, traps and rod and line. Generally static /passive gear has a lower impact on the seabed. Here are the most commonly used fishing methods with a brief explanation of how they work and their environmental impacts. Beam trawl In this type of trawl, the mouth or opening of the net is kept open by a beam, which is mounted at each end on guides or skids which travel along the seabed. The trawls are adapted and made more effective by attaching tickler chains (for sand or mud) or heavy chain matting (for rough, rocky ground) depending on the type of ground being fished. These drag along the seabed in front of the net, disturbing the fish in the path of the trawl, causing them to rise from the seabed into the oncoming net. Electrified ticklers, which are less damaging to the seabed, have been developed but used only experimentally. Work is also being carried out to investigate whether square mesh panels (see below) fitted in the ‘belly’ or lower panel of the net can reduce the impact of beam trawling on communities living on or in the seabed.