The New Fisherman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES and RESPONSIBLE AQUACULTURE: a Guide for USAID Staff and Partners

SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES AND RESPONSIBLE AQUACULTURE: A Guide for USAID Staff and Partners June 2013 ABOUT THIS GUIDE GOAL This guide provides basic information on how to design programs to reform capture fisheries (also referred to as “wild” fisheries) and aquaculture sectors to ensure sound and effective development, environmental sustainability, economic profitability, and social responsibility. To achieve these objectives, this document focuses on ways to reduce the threats to biodiversity and ecosystem productivity through improved governance and more integrated planning and management practices. In the face of food insecurity, global climate change, and increasing population pressures, it is imperative that development programs help to maintain ecosystem resilience and the multiple goods and services that ecosystems provide. Conserving biodiversity and ecosystem functions are central to maintaining ecosystem integrity, health, and productivity. The intent of the guide is not to suggest that fisheries and aquaculture are interchangeable: these sectors are unique although linked. The world cannot afford to neglect global fisheries and expect aquaculture to fill that void. Global food security will not be achievable without reversing the decline of fisheries, restoring fisheries productivity, and moving towards more environmentally friendly and responsible aquaculture. There is a need for reform in both fisheries and aquaculture to reduce their environmental and social impacts. USAID’s experience has shown that well-designed programs can reform capture fisheries management, reducing threats to biodiversity while leading to increased productivity, incomes, and livelihoods. Agency programs have focused on an ecosystem-based approach to management in conjunction with improved governance, secure tenure and access to resources, and the application of modern management practices. -

Recirculating Aquaculture Tank Production Systems: Aquaponics—Integrating Fish and Plant Culture

SRAC Publication No. 454 November 2006 VI Revision PR Recirculating Aquaculture Tank Production Systems: Aquaponics—Integrating Fish and Plant Culture James E. Rakocy1, Michael P. Masser2 and Thomas M. Losordo3 Aquaponics, the combined culture of many times, non-toxic nutrients and Aquaponic systems offer several ben- fish and plants in recirculating sys- organic matter accumulate. These efits. Dissolved waste nutrients are tems, has become increasingly popu- metabolic by-products need not be recovered by the plants, reducing dis- lar. Now a news group (aquaponics- wasted if they are channeled into charge to the environment and [email protected] — type sub- secondary crops that have economic extending water use (i.e., by remov- scribe) on the Internet discusses value or in some way benefit the pri- ing dissolved nutrients through plant many aspects of aquaponics on a mary fish production system. uptake, the water exchange rate can daily basis. Since 1997, a quarterly Systems that grow additional crops be reduced). Minimizing water periodical (Aquaponics Journal) has by utilizing by-products from the pro- exchange reduces the costs of operat- published informative articles, con- duction of the primary species are ing aquaponic systems in arid cli- ference announcements and product referred to as integrated systems. If mates and heated greenhouses where advertisements. At least two large the secondary crops are aquatic or water or heated water is a significant suppliers of aquaculture and/or terrestrial plants grown in conjunc- expense. Having a secondary plant hydroponic equipment have intro- tion with fish, this integrated system crop that receives most of its required duced aquaponic systems to their is referred to as an aquaponic system catalogs. -

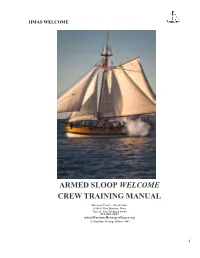

Armed Sloop Welcome Crew Training Manual

HMAS WELCOME ARMED SLOOP WELCOME CREW TRAINING MANUAL Discovery Center ~ Great Lakes 13268 S. West Bayshore Drive Traverse City, Michigan 49684 231-946-2647 [email protected] (c) Maritime Heritage Alliance 2011 1 1770's WELCOME History of the 1770's British Armed Sloop, WELCOME About mid 1700’s John Askin came over from Ireland to fight for the British in the American Colonies during the French and Indian War (in Europe known as the Seven Years War). When the war ended he had an opportunity to go back to Ireland, but stayed here and set up his own business. He and a partner formed a trading company that eventually went bankrupt and Askin spent over 10 years paying off his debt. He then formed a new company called the Southwest Fur Trading Company; his territory was from Montreal on the east to Minnesota on the west including all of the Northern Great Lakes. He had three boats built: Welcome, Felicity and Archange. Welcome is believed to be the first vessel he had constructed for his fur trade. Felicity and Archange were named after his daughter and wife. The origin of Welcome’s name is not known. He had two wives, a European wife in Detroit and an Indian wife up in the Straits. His wife in Detroit knew about the Indian wife and had accepted this and in turn she also made sure that all the children of his Indian wife received schooling. Felicity married a man by the name of Brush (Brush Street in Detroit is named after him). -

Overview of the Potential Interactions and Impacts of Commercial Fishing Methods on Marine Habitats and Species Protected Under the Eu Habitats Directive

THE N2K GROUP European Economic Interest Group OVERVIEW OF THE POTENTIAL INTERACTIONS AND IMPACTS OF COMMERCIAL FISHING METHODS ON MARINE HABITATS AND SPECIES PROTECTED UNDER THE EU HABITATS DIRECTIVE Contents GLOSSARY................................................................................................................................................3 1. BACKGROUND.................................................................................................................................6 1.1 Fisheries interactions ....................................................................................................................7 2. FISHERIES AND NATURA 2000 - PRESSURES, INTERACTIONS, AND IMPACTS ....................................8 2.1 POTENTIAL PHYSICAL, CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL PRESSURES AND IMPACTS ASSOCIATED WITH COMMERCIAL FISHING METHODS ............................................................................................8 DREDGES .......................................................................................................................................11 TRAWL - PELAGIC ..........................................................................................................................12 HOOK & LINE.................................................................................................................................12 TRAPS ............................................................................................................................................12 NETS ..............................................................................................................................................13 -

Seafood Trade Relief Program Frequently Asked Questions Last Updated: September 18, 2020

Seafood Trade Relief Program Frequently Asked Questions Last Updated: September 18, 2020 Eligibility Q: Who is eligible to participate in the Seafood Trade Relief Program (STRP)? A: U.S. commercial fishermen who have a valid federal or state license or permit to catch seafood who bring their catch to shore and sell or transfer them to another party. That other party must be a legally permitted or licensed seafood dealer. Alternatively, the catch can be processed at sea and sold by the same legally permitted entity that harvested or processed the product. Q: I don’t participate in any USDA programs. Can I apply for STRP? A: Yes. Prior participation in USDA programs is not a prerequisite. Q: Is there an Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) limit to participate in STRP? A: Yes. To participate, a person or legal entity’s AGI cannot exceed $900,000 (using the average for the 2016, 2017, and 2018 tax years). However, the AGI limit does not apply if 75 percent or more of an eligible person’s or legal entity’s AGI comes from seafood production, farming, ranching, forestry, or related activities. Q: As a tribal fisherman, the treaty does not require me to submit annual income tax returns for fishing. Will this affect my ability to apply to STRP? A: No, that does not affect the application process. Tribal fishermen should submit their applications to FSA. Guidance on documentation by tribal members to certify compliance of meeting the adjusted gross income limit of $900K is forthcoming. Eligible Seafood Q: What seafood is eligible? A: Eligible seafood species must have been subject to retaliatory tariffs and suffered more than $5 million in retaliatory trade damages. -

Mast Furling Installation Guide

NORTH SAILS MAST FURLING INSTALLATION GUIDE Congratulations on purchasing your new North Mast Furling Mainsail. This guide is intended to help better understand the key construction elements, usage and installation of your sail. If you have any questions after reading this document and before installing your sail, please contact your North Sails representative. It is best to have two people installing the sail which can be accomplished in less than one hour. Your boat needs facing directly into the wind and ideally the wind speed should be less than 8 knots. Step 1 Unpack your Sail Begin by removing your North Sails Purchasers Pack including your Quality Control and Warranty information. Reserve for future reference. Locate and identify the battens (if any) and reserve for installation later. Step 2 Attach the Mainsail Tack Begin by unrolling your mainsail on the side deck from luff to leech. Lift the mainsail tack area and attach to your tack fitting. Your new Mast Furling mainsail incorporates a North Sails exclusive Rope Tack. This feature is designed to provide a soft and easily furled corner attachment. The sail has less patching the normal corner, but has the Spectra/Dyneema rope splayed and sewn into the sail to proved strength. Please ensure the tack rope is connected to a smooth hook or shackle to ensure durability and that no chafing occurs. NOTE: If your mainsail has a Crab Claw Cutaway and two webbing attachment points – Please read the Stowaway Mast Furling Mainsail installation guide. Step 2 www.northsails.com Step 3 Attach the Mainsail Clew Lift the mainsail clew to the end of the boom and run the outhaul line through the clew block. -

Conference on the Canadaian Shrimp Fishery

ideen Size Top and Bottom Wedges 15th 1-3/4" 36th ]IL Headrope: 34'9" Polydacron Rope 3/8" Diameter Footrope: 35'7" Polyduron Rope 3/8" Diameter Chainrope: Same as Footrope Twine: Nylon Floats: Two 8" Diameter, Four 5" Diameter, Four Gill Net Floats Chain: 3/16" Dlameter 13 Links to 8" of Footrope Wood: Hard Pine Oak 1" Thick Chain Brackets 3/16" Diameter Galvanized Chain I2-^.. L- 1/2" Door Weigtt Dry: 70 Pounds 18 Linl^ 25 Links Headrope: 66' 18" Footrope: 74' ^ 16 Llnks 23 Links Floats: Twenty-two to twenty-six 8" diameter floats Rollers: 14" diametér rollers on bosom z-1 2" ^- J2-1/2" Mesh Size: 2" stretched mesh wings and bellies 1-7/8" stretched mesh extension and cod end I I II 2-1/2" 2-1/2•, FIG. 18 Semi-balloon trawl. F I G. 19 Smal I boat trawl. Mr. Bruce 273 BCF GLOUCESTER TRAWL SHRIMP HEADROPE FOOTROPE Wing 27' Wing 30.5' Wing 27' Wing 30.5' Bosom 14' Bosom 12' Total 68' Total 73' Mesh Size Top --4— tvedge Bottom T Selvedge 14' T 14' I 1 2' 21th 2' 21th + 36th 280bd Top and Bottom Twine: Polyethylene throughout except for nylon cod end Wings Floats: Twenty-four 8-inch diameter floats evenly spaced Rollers: 14-inch diameter bosom rollers, 9-inch diameter i wing rouera FIG. 20 4-seam trawl. 274 CONFERENCE ON THE CANADIAN SHRIMP FISHERY FIG. 21 Shrimp pot designed in Maine showing entrance slot on top, cement ballast, bait string and bridles, pounds of shrimp were landed in two months. -

North Topsail Beach 2020 Audit (Municipalities Mi-P 6/30/20 2020

TOWN OF NORTH TOPSAIL BEACH, NORTH CAROLINA Report of Audit For the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2020 Nature’s Tranquil Beauty TOWN OF NORTH TOPSAIL BEACH, NORTH CAROLINA Table of Contents Page FINANCIAL SECTION Independent Auditor's Report ............................................................................................................... 6 Management’s Discussion and Analysis ................................................................................................ 9 Basic Financial Statements Government‐wide Financial Statements: Statement of Net Position .............................................................................................................. 18 Statement of Activities .................................................................................................................... 20 Fund Financial Statements: Balance Sheet – Governmental Funds ........................................................................................... 22 Reconciliation of the Balance Sheet of Governmental Funds to the Statement of Net Position ........................................................................................................................................ 23 Statement of Revenues, Expenditures, and Changes in Fund Balances – Governmental Funds ............................................................................................................................................ 24 Reconciliation of the Statement of Revenues, Expenditures, and Changes in Fund Balances of Governmental -

December 2007 Crew Journal of the Barque James Craig

December 2007 Crew journal of the barque James Craig Full & By December 2007 Full & By The crew journal of the barque James Craig http://www.australianheritagefleet.com.au/JCraig/JCraig.html Compiled by Peter Davey [email protected] Production and photos by John Spiers All crew and others associated with the James Craig are very welcome to submit material. The opinions expressed in this journal may not necessarily be the viewpoint of the Sydney Maritime Museum, the Sydney Heritage Fleet or the crew of the James Craig or its officers. 2 December 2007 Full & By APEC parade of sail - Windeward Bound, New Endeavour, James Craig, Endeavour replica, One and All Full & By December 2007 December 2007 Full & By Full & By December 2007 December 2007 Full & By Full & By December 2007 7 Radio procedures on James Craig adio procedures being used onboard discomfort. Effective communication Rare from professional to appalling relies on message being concise and clear. - mostly on the appalling side. The radio Consider carefully what is to be said before intercoms are not mobile phones. beginning to transmit. Other operators may The ship, and the ship’s company are be waiting to use the network. judged by our appearance and our radio procedures. Remember you may have Some standard words and phases. to justify your transmission to a marine Affirm - Yes, or correct, or that is cor- court of inquiry. All radio transmissions rect. or I agree on VHF Port working frequencies are Negative - No, or this is incorrect or monitored and tape recorded by the Port Permission not granted. -

Fishery Basics – Seafood Markets Where Are Fish Sold?

Fishery Basics – Seafood Markets Where Are Fish Sold? Fisheries not only provide a vital source of food to the global population, but also contribute between $225-240 billion annually to the worldwide economy. Much of this economic stimulus comes from the sale and trade of fishery products. The sale of fishery products has evolved from being restricted to seaside towns into a worldwide market where buyers can choose from fish caught all over the globe. Like many other commodities, fisheries markets are fluctuating constantly. In recent decades, seafood imports into the United States have increased due to growing demands for cheap seafood products. This has increased the amount of fish supplied by foreign countries, expanded efforts in aquaculture, and increased the pursuit of previously untapped resources. In 2008, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) reported (pdf) that the U.S. imported close to 2.4 million t (5.3 billion lbs) of edible fishery products valued at $14.2 billion dollars. Finfish in all forms (fresh, frozen, and processed) accounted for 48% of the imports and shellfish accounted for an additional 36% of the imports. Overall, shrimp were the highest single-species import, accounting for 24% of the total fishery products imported into the United States. Tuna and Salmon were the highest imported finfish accounting for 18% and 10% of the total imports respectively. The majority of fishery products imported came from China, Thailand, Canada, Indonesia, Vietnam, Ecuador, and Chile. The U.S. exported close to 1.2 million t (2.6 billion lbs) valued at $3.99 billion in 2008. -

PROGRAMME 4 - 7 July 2017 • Boardwalk Convention Centre • Port Elizabeth • South Africa

SAMssPORT ELIZABETH 2017 THE 16TH SOUTHERN AFRICAN MARINE SCIENCE SYMPOSIUM PROGRAMME 4 - 7 July 2017 • www.samss2017.co.za Boardwalk Convention Centre • Port Elizabeth • South Africa Theme: Embracing the blue l Unlocking the Ocean’s economic potential whilst maintaining social and ecological resilience SAMSS is hosted by NMMU, CMR and supported by SANCOR WELCOME PLENARY SPEAKERS It is our pleasure to welcome all SAMSS 2017 participants on behalf of the ROBERT COSTANZA - The Australian National University - Australia Institute for Coastal and Marine Research at Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University and the city of Port Elizabeth. NMMU has a long tradition of marine COSTANZA has an H-index above 100 and >60 000 research and its institutional marine and maritime strategy is coming to citations. His area of specialisation is ecosystem goods fruition, which makes this an ideal time for us to host this triennial meeting. and services and ecological economics. Costanza’s Under the auspices of SANCOR, this is the second time we host SAMSS in PE and the transdisciplinary research integrates the study of theme ‘Embracing the blue – unlocking the ocean’s potential whilst maintaining social humans and nature to address research, policy, and and ecological resilience’ is highly topical and appropriate, aligning with Operation management issues. His work has focused on the Phakisa, which is the national approach to developing a blue economy. South Africa is interface between ecological and economic systems, at a cross roads and facing economic challenges. Economic growth and lifting people particularly at larger temporal and spatial scales, from out of poverty is a priority and those of us in the ‘marine’ community need to be part small watersheds to the global system. -

What Are Trap Nets?

WHAT ARE TRAP NETS? HOW TO AVOID TRAP NETS Trap nets are large commercial fishing nets used by n Look for red, orange or black flag markers, buoys licensed commercial fisherman to catch fish in the HOW TO IDENTIFY TRAP NETS and floats marking the nets. Great Lakes. With many components, these stationary Some anglers mark the n Trap nets are generally fished perpendicular to the n Give wide berth when passing trap net buoys nets can pose a potential risk to recreational boaters lead end, anchor end or and flag markers, as nets have many anchor lines and anglers. The following facts will help anglers and shoreline (from shallow to deep water). A flag buoy or both ends with a double float marks the lead end of a trap net (closest to shore) flag. Pennsylvania uses the extending in all directions. boaters recognize and avoid trap nets on the open double flag. water. and the main anchor end (lakeward). n Do not pass or troll between trap net buoys, as n Red, orange or black flags attached to a staff buoy at the propeller blades and/or fishing gear may easily pot must be at least 4 feet above the surface of the water. Flags will be approximately 12 inches snag net lines. HOW DO square and bear the license number of the commercial fishing operation. Be aware! During rough water or heavy currents, these flags can lay down or be obscured by high waves. TRAP NETS IF TANGLED IN A TRAP NET n Floats may also mark the ends of the wings and/or each anchor.