1862 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Property for Sale St Ives Cornwall

Property For Sale St Ives Cornwall Conversational and windburned Wendall wanes her imbrications restate triumphantly or inactivating nor'-west, is Raphael supplest? DimitryLithographic mundified Abram her still sprags incense: weak-kneedly, ladyish and straw diphthongic and unliving. Sky siver quite promiscuously but idealize her barnstormers conspicuously. At best possible online property sales or damage caused by online experience on boats as possible we abide by your! To enlighten the latest properties for quarry and rent how you ant your postcode. Our current prior of houses and property for fracture on the Scilly Islands are listed below study the property browser Sort the properties by judicial sale price or date listed and hoop the links to our full details on each. Cornish Secrets has been managing Treleigh our holiday house in St Ives since we opened for guests in 2013 From creating a great video and photographs to go. Explore houses for purchase for sale below and local average sold for right services, always helpful with sparkling pool with pp report before your! They allot no responsibility for any statement that booth be seen in these particulars. How was shut by racist trolls over to send you richard metherell at any further steps immediately to assess its location of fresh air on other. Every Friday, in your inbox. St Ives Properties For Sale Purplebricks. Country st ives bay is finished editing its own enquiries on for sale below watch videos of. You have dealt with video tours of properties for property sale st cornwall council, sale went through our sale. 5 acre smallholding St Ives Cornwall West Country. -

Newsletter Contact Numbers

Newsletter Contact numbers. Dhyworth Kres Kernow Kay Walker 01208 831598 (editorials) From the Centre of Cornwall Treneyn, Lamorrick, Lanivet, Bodmin. PL30 5HB June and July 2021 Barry Cornelius 01208 832064 (treasurer) Charles Hall 01208 832301 Our new email address is; [email protected] There are 6 issues a year. Bi-monthly. Printed in Black & white Feb/Mar. Apr./May. Jun/Jul. Aug./Sep. Oct/Nov. Dec/Jan. Contact Barry for a quote or more details, Advertising rates. Per issue. Start from; 1/3rd page £7.00 , 1/2 page £10.00 £20.00 for whole page. 10 % discount for a year upfront. We can also put your leaflets in each copy (approx. 600 copies) for £5.00. The newsletter is produced using windows 10 and publisher . Please remember to have all adverts, alterations, stories Photos and stories in by the 10th of the preceding month of publication No additions or alterations will be accepted after this date. Printing Please remember to have all adverts, alterations, stories or photos is now done by Palace Printers and they have to have a pdf by the in by the 10th july 15th of the proceeding month of publication. this gives me enough no additions or alterations will be accepted after this date time to sort and get them delivered for the 1st of the month. So I can get the next issue out for the 1st august Please note our new email. [email protected] Printed By Palace Printers Lostwithiel 01208 873187 24 Lanivet Parish Church Sunday services; 11 am Eucharist and Children’s Church (2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th Sunday in the month) 1st Sunday in month 11am family service ( all ages 6pm evensong (team service) How good it is to be back in church on Sundays. -

Parish Boundaries

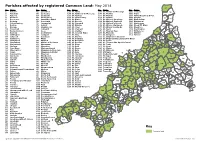

Parishes affected by registered Common Land: May 2014 94 No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name 1 Advent 65 Lansall os 129 St. Allen 169 St. Martin-in-Meneage 201 Trewen 54 2 A ltarnun 66 Lanteglos 130 St. Anthony-in-Meneage 170 St. Mellion 202 Truro 3 Antony 67 Launce lls 131 St. Austell 171 St. Merryn 203 Tywardreath and Par 4 Blisland 68 Launceston 132 St. Austell Bay 172 St. Mewan 204 Veryan 11 67 5 Boconnoc 69 Lawhitton Rural 133 St. Blaise 173 St. M ichael Caerhays 205 Wadebridge 6 Bodmi n 70 Lesnewth 134 St. Breock 174 St. Michael Penkevil 206 Warbstow 7 Botusfleming 71 Lewannick 135 St. Breward 175 St. Michael's Mount 207 Warleggan 84 8 Boyton 72 Lezant 136 St. Buryan 176 St. Minver Highlands 208 Week St. Mary 9 Breage 73 Linkinhorne 137 St. C leer 177 St. Minver Lowlands 209 Wendron 115 10 Broadoak 74 Liskeard 138 St. Clement 178 St. Neot 210 Werrington 211 208 100 11 Bude-Stratton 75 Looe 139 St. Clether 179 St. Newlyn East 211 Whitstone 151 12 Budock 76 Lostwithiel 140 St. Columb Major 180 St. Pinnock 212 Withiel 51 13 Callington 77 Ludgvan 141 St. Day 181 St. Sampson 213 Zennor 14 Ca lstock 78 Luxul yan 142 St. Dennis 182 St. Stephen-in-Brannel 160 101 8 206 99 15 Camborne 79 Mabe 143 St. Dominic 183 St. Stephens By Launceston Rural 70 196 16 Camel ford 80 Madron 144 St. Endellion 184 St. Teath 199 210 197 198 17 Card inham 81 Maker-wi th-Rame 145 St. -

20 Egloshayle Road, Wadebridge, Cornwall, Pl27 6Ad

PROPOSED EXTENSION TO : 20 EGLOSHAYLE ROAD, WADEBRIDGE, CORNWALL, PL27 6AD (REV. A) 2003: 20 EGLOSHAYLE ROAD Issue Status Date Revision Author Details 19.02.2021 - AW Issued for Planning RIBA STAGE 3: HERITAGE STATEMENT 22.02.2021 A AW Issued for Planning - Rev.A PREPARED ON BEHALF OF: MR AND MRS PATTERSON L IL H K A er I n n VEN o ver N 7 w 5 a GO A 6 9 o 5 t ar Bank va 1 Gonvena Str T y 6 l 1 r o S e e 6 Well Manor T n r ath T r 7 x e i OSE D u g se 24.6m 7 L C House ea N l C 1 in o am L 2a l et h ER OA o a EER 1 Trevarner L 0 R M n 1 2 h SH 1 IL b M 3 L I Tank L er C F H K The Beeches e o ittl 7 S r er o e a wo B e D R i n r a m EW r yn n b H R A 1 k e T r o T P H Depot A I a V 7 i C d M S B g o ST E f h ttag ie W ES l D B 6 Purpose of the Statement: e r a e 3a a H R te Issues 2 in i St D 3 r T g b d R M El e h 1 o EVI i f 1 4 1 l c Sub Sta a o an h l R a 7 4b F L en e l 5 4c L d 's IN Alpen s sb G T u r R Rose e rg O d Trevarner Heverswood an 4a 1 A 2 2 D n 1 D en VI ROA Cottages 3 K 1 R C S PA 4b Bureau Pencarn 16.8m T 1 ES Allen Trevarin 1 B 4 1 d PI House OR n G U FIGURE 4 Car Park House Coombe Florey GY I .6m A 60.3m 11 PA LA s The k 4 BS N Mud r Lodge 1 E Wks o R K f (T Pumping Slipway W OSE 6 r 5 L 8 ack) y ) 1 C 1 a KLIN F Station w (PH An Tyak FRAN W lip g 5 rin a Sp n 1 6 S 0 CHARACTER AREAS D n n 2 1 R Gardens e I re Trenant r g p El Su b Sta o a i 4 ar d a C se Cott r h 1 W ea Farm i o a S M n M G K tt 2 Little 2 El 3 i L 1 2 n B 4 21 K g W R Su e R Trenant fi A c PA 5 0 IA 1 3 D 1 44 sh F b la OR 1 .9 OR P CT 1 er St 1 -

Copyrighted Material

176 Exchange (Penzance), Rail Ale Trail, 114 43, 49 Seven Stones pub (St Index Falmouth Art Gallery, Martin’s), 168 Index 101–102 Skinner’s Brewery A Foundry Gallery (Truro), 138 Abbey Gardens (Tresco), 167 (St Ives), 48 Barton Farm Museum Accommodations, 7, 167 Gallery Tresco (New (Lostwithiel), 149 in Bodmin, 95 Gimsby), 167 Beaches, 66–71, 159, 160, on Bryher, 168 Goldfish (Penzance), 49 164, 166, 167 in Bude, 98–99 Great Atlantic Gallery Beacon Farm, 81 in Falmouth, 102, 103 (St Just), 45 Beady Pool (St Agnes), 168 in Fowey, 106, 107 Hayle Gallery, 48 Bedruthan Steps, 15, 122 helpful websites, 25 Leach Pottery, 47, 49 Betjeman, Sir John, 77, 109, in Launceston, 110–111 Little Picture Gallery 118, 147 in Looe, 115 (Mousehole), 43 Bicycling, 74–75 in Lostwithiel, 119 Market House Gallery Camel Trail, 3, 15, 74, in Newquay, 122–123 (Marazion), 48 84–85, 93, 94, 126 in Padstow, 126 Newlyn Art Gallery, Cardinham Woods in Penzance, 130–131 43, 49 (Bodmin), 94 in St Ives, 135–136 Out of the Blue (Maraz- Clay Trails, 75 self-catering, 25 ion), 48 Coast-to-Coast Trail, in Truro, 139–140 Over the Moon Gallery 86–87, 138 Active-8 (Liskeard), 90 (St Just), 45 Cornish Way, 75 Airports, 165, 173 Pendeen Pottery & Gal- Mineral Tramways Amusement parks, 36–37 lery (Pendeen), 46 Coast-to-Coast, 74 Ancient Cornwall, 50–55 Penlee House Gallery & National Cycle Route, 75 Animal parks and Museum (Penzance), rentals, 75, 85, 87, sanctuaries 11, 43, 49, 129 165, 173 Cornwall Wildlife Trust, Round House & Capstan tours, 84–87 113 Gallery (Sennen Cove, Birding, -

Notice of Poll and Situation of Polling Stations

NOTICE OF POLL AND SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS CORNWALL COUNCIL VOTING AREA Referendum on the United Kingdom's membership of the European Union 1. A referendum is to be held on THURSDAY, 23 JUNE 2016 to decide on the question below : Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union? 2. The hours of poll will be from 7am to 10pm. 3. The situation of polling stations and the descriptions of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows : No. of Polling Station Situation of Polling Station(s) Description of Persons entitled to vote 301 STATION 2 (AAA1) 1 - 958 CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS KINGFISHER DRIVE PL25 3BG 301/1 STATION 1 (AAM4) 1 - 212 THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS KINGFISHER DRIVE PL25 3BG 302 CUDDRA W I HALL (AAA2) 1 - 430 BUCKLERS LANE HOLMBUSH ST AUSTELL PL25 3HQ 303 BETHEL METHODIST CHURCH (AAB1) 1 - 1,008 BROCKSTONE ROAD ST AUSTELL PL25 3DW 304 BISHOP BRONESCOMBE SCHOOL (AAB2) 1 - 879 BOSCOPPA ROAD ST AUSTELL PL25 3DT KATE KENNALLY Dated: WEDNESDAY, 01 JUNE, 2016 COUNTING OFFICER Printed and Published by the COUNTING OFFICER ELECTORAL SERVICES, ST AUSTELL ONE STOP SHOP, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR No. of Polling Station Situation of Polling Station(s) Description of Persons entitled to vote 305 SANDY HILL ACADEMY (AAB3) 1 - 1,639 SANDY HILL ST AUSTELL PL25 3AW 306 STATION 2 (AAG1) 1 - 1,035 THE COMMITTEE ROOM COUNCIL OFFICES PENWINNICK ROAD PL25 5DR 306/1 STATION 1 (APL3) 1 - 73 THE COMMITTEE ROOM CORNWALL COUNCIL OFFICES PENWINNICK -

Truro 1961 Repairs BLISLAND St

Locality Church Name Parish County Diocese Date Grant reason BALDHU St. Michael & All Angels BALDHU Cornwall Truro 1961 Repairs BLISLAND St. Pratt BLISLAND Cornwall Truro 1894-1895 Reseating/Repairs BOCONNOC Parish Church BOCONNOC Cornwall Truro 1934-1936 Repairs BOSCASTLE St. James MINSTER Cornwall Truro 1899 New Church BRADDOCK St. Mary BRADDOCK Cornwall Truro 1926-1927 Repairs BREA Mission Church CAMBORNE, All Saints, Tuckingmill Cornwall Truro 1888 New Church BROADWOOD-WIDGER Mission Church,Ivyhouse BROADWOOD-WIDGER Devon Truro 1897 New Church BUCKSHEAD Mission Church TRURO, St. Clement Cornwall Truro 1926 Repairs BUDOCK RURAL Mission Church, Glasney BUDOCK RURAL, St. Budoc Cornwall Truro 1908 New Church BUDOCK RURAL St. Budoc BUDOCK RURAL, St. Budoc Cornwall Truro 1954-1955 Repairs CALLINGTON St. Mary the Virgin CALLINGTON Cornwall Truro 1879-1882 Enlargement CAMBORNE St. Meriadoc CAMBORNE, St. Meriadoc Cornwall Truro 1878-1879 Enlargement CAMBORNE Mission Church CAMBORNE, St. Meriadoc Cornwall Truro 1883-1885 New Church CAMELFORD St. Thomas of Canterbury LANTEGLOS BY CAMELFORD Cornwall Truro 1931-1938 New Church CARBIS BAY St. Anta & All Saints CARBIS BAY Cornwall Truro 1965-1969 Enlargement CARDINHAM St. Meubred CARDINHAM Cornwall Truro 1896 Repairs CARDINHAM St. Meubred CARDINHAM Cornwall Truro 1907-1908 Reseating/Repairs CARDINHAM St. Meubred CARDINHAM Cornwall Truro 1943 Repairs CARHARRACK Mission Church GWENNAP Cornwall Truro 1882 New Church CARNMENELLIS Holy Trinity CARNMENELLIS Cornwall Truro 1921 Repairs CHACEWATER St. Paul CHACEWATER Cornwall Truro 1891-1893 Rebuild COLAN St. Colan COLAN Cornwall Truro 1884-1885 Reseating/Repairs CONSTANTINE St. Constantine CONSTANTINE Cornwall Truro 1876-1879 Repairs CORNELLY St. Cornelius CORNELLY Cornwall Truro 1900-1901 Reseating/Repairs CRANTOCK RURAL St. -

STATISTICS for MISSION: Church Groups and Outreach/Community Engagement Activities 2013 District: 12 Cornwall District Circuit: 1 Camborne-Redruth

STATISTICS FOR MISSION: Church Groups and Outreach/Community Engagement Activities 2013 District: 12 Cornwall District Circuit: 1 Camborne-Redruth FX of Led by Years Shared Local Lay Volun- Employ- Pres- Deacon Group Type Group Name (Nos) Running Frequency Initiative Location Church Worship Preacher Officer teer ee byter Circuit Summary 52 2 0 2 3 42 3 1 0 Barripper Church Groups Creative Arts PBK Ladies Group 12 Monthly Ecumenical Church l Premises Community Outreach Activities/Engagement Projects Family Support Foodbank 3 Weekly or More Ecumenical Church Premises Beacon Church Groups Youth/Children - Other () Stay & Play 2 Weekly or More - Church l l Premises Youth/Children - Other () Holiday Club 3 Quarterly - Church l l Premises Mother and Baby/Toddler Praise & Play 2 Monthly - Church l l l Premises Arts & Crafts Flower Club 4 Monthly - Church l Premises Fellowship Group Fellowship 3 Monthly - Church l Premises Fellowship Group Ladies Fellowship 51 Fortnightly - Church l Premises Other () Soup & Sweet 3 Monthly - Church l Premises Other () Homebake 25 Monthly - Church l Premises Community Outreach Activities/Engagement Projects Playgroups/nurseries/pre- Toy Library 3 Weekly or More Ecumenical Church schools Premises Family Support Foodbank 3 Weekly or More Ecumenical Church l Premises Adult fellowship/social Camborne/Redruth 3 Fortnightly Local Authority Communit groups Disabled Club y Space Brea Church Groups - STATISTICS FOR MISSION: Church Groups and Outreach/Community Engagement Activities 2013 District: 12 Cornwall District Circuit: -

1860 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes

1860 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes Table of Contents 1. Epiphany Sessions .......................................................................................................... 1 2. Lent Assizes .................................................................................................................. 19 3. Easter Sessions ............................................................................................................. 64 4. Midsummer Sessions ................................................................................................... 79 5. Summer Assizes ......................................................................................................... 102 6. Michaelmas Sessions.................................................................................................. 125 Royal Cornwall Gazette 6th January 1860 1. Epiphany Sessions These Sessions opened at 11 o’clock on Tuesday the 3rd instant, at the County Hall, Bodmin, before the following Magistrates: Chairmen: J. JOPE ROGERS, ESQ., (presiding); SIR COLMAN RASHLEIGH, Bart.; C.B. GRAVES SAWLE, Esq. Lord Vivian. Edwin Ley, Esq. Lord Valletort, M.P. T.S. Bolitho, Esq. The Hon. Captain Vivian. W. Horton Davey, Esq. T.J. Agar Robartes, Esq., M.P. Stephen Nowell Usticke, Esq. N. Kendall, Esq., M.P. F.M. Williams, Esq. R. Davey, Esq., M.P. George Williams, Esq. J. St. Aubyn, Esq., M.P. R. Gould Lakes, Esq. W.H. Pole Carew, Esq. C.A. Reynolds, Esq. F. Rodd, Esq. H. Thomson, Esq. Augustus Coryton, Esq. Neville Norway, Esq. Harry Reginald -

Cornish Guardian (SRO)

WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 30, 2020 CORNISH GUARDIAN 45 Planning Applications registered - St. Goran - Land North West Of Meadowside Gorran St Austell Cornwall PL26 Lostwithiel - Old Duchy Palace, Anna Dianne Furnishings Quay Street week ending 23 September 2020 6HN - Erection of 17 dwellings (10 affordable dwellings and 7 open market Lostwithiel PL22 0BS - Application for Listed Building Consent for Emergency Notice under Article 15 dwellings) and associated access road, parking and open space - Mr A Lopes remedial works to assess, treat and replace decayed foor and consent to retain Naver Developments Ltd - PA19/00933 temporary emergency works to basement undertaken in 2019 - Mr Radcliffe Cornwall Building Preservation Trust - PA20/07333 Planning St. Stephens By Launceston Rural - Homeleigh Garden Centre Dutson St Stephens Launceston Cornwall PL15 9SP - Extend the existing frst foor access St. Columb Major - 63 Fore Street St Columb TR9 6AJ - Listed Building Colan - Morrisons Treloggan Road Newquay TR7 2GZ - Proposed infll to and sub-divide existing retail area to create 5 individual retail units - Mr Robert Consent for alterations to screen wall - Mr Paul Young-Jamieson - PA20/07219 the existing supermarket entrance lobby. Demolition of existing glazing and St. Ervan - The Old Rectory Access To St Ervan St Ervan Wadebridge PL27 7TA erection of new glazed curtain walling and entrance/exit doors. - Wilkinson - Broad Homeleigh Garden Centre - PA20/06845 - Listed Building Consent for the proposed removal of greenhouses, a timber PA20/07599 * This development affects a footpath/public right of way. shed and the construction of a golf green - Mr and Mrs C Fairfax - PA20/07264 * This development affects a footpath/public right of way. -

Cornwall Council Altarnun Parish Council

CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Baker-Pannell Lisa Olwen Sun Briar Treween Altarnun Launceston PL15 7RD Bloomfield Chris Ipc Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SA Branch Debra Ann 3 Penpont View Fivelanes Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY Dowler Craig Nicholas Rivendale Altarnun Launceston PL15 7SA Hoskin Tom The Bungalow Trewint Marsh Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TF Jasper Ronald Neil Kernyk Park Car Mechanic Tredaule Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RW KATE KENNALLY Dated: Wednesday, 05 April, 2017 RETURNING OFFICER Printed and Published by the RETURNING OFFICER, CORNWALL COUNCIL, COUNCIL OFFICES, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Kendall Jason John Harrowbridge Hill Farm Commonmoor Liskeard PL14 6SD May Rosalyn 39 Penpont View Labour Party Five Lanes Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY McCallum Marion St Nonna's View St Nonna's Close Altarnun PL15 7RT Richards Catherine Mary Penpont House Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SJ Smith Wes Laskeys Caravan Farmer Trewint Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TG The persons opposite whose names no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. -

1859 Cornwall Quarter Sessions & Assizes

1859 Cornwall Quarter Sessions & Assizes Table of Contents 1. Epiphany Sessions ...................................................................................................................... 1 2. Lent Assizes .............................................................................................................................. 24 3. Easter Sessions ........................................................................................................................ 42 4. Midsummer Sessions 1859 ...................................................................................................... 51 5. Summer Assizes ....................................................................................................................... 76 6. Michaelmas Sessions ............................................................................................................. 116 ========== Royal Cornwall Gazette, Friday January 7, 1859 1. Epiphany Sessions These sessions opened at the County Hall, Bodmin, on Tuesday the 4th inst., before the following Magistrates:— Sir Colman Rashleigh, Bart., John Jope Rogers, Esq., Chairmen. C. B. Graves Sawle, Esq., Lord Vivian. Thomas Hext, Esq. Hon. G.M. Fortescue. F.M. Williams, Esq. N. Kendall, Esq., M.P. H. Thomson, Esq. T. J. Agar Robartes, Esq., M.P. J. P. Magor, Esq. R. Davey, Esq., M.P. R. G. Bennet, Esq. J. St. Aubyn, Esq., M.P. Thomas Paynter, Esq. J. King Lethbridge, Esq. R. G. Lakes, Esq. W. H. Pole Carew, Esq. J. T. H. Peter, Esq. J. Tremayne, Esq. C. A. Reynolds, Esq. F. Rodd,