What Drives Warming Trends in Streams? a Case Study from the Alpine Foothills

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sistemazione Fiume Vedeggio

Convegno WWF - Biodiversità nella regione dei Laghi Insubrici Lugano, 1° giugno 2012 Il recupero dei corsi d’acqua Evoluzione dei criteri di gestione dei corsi d’acqua Laurent Filippini Cantone Ticino Ufficio dei corsi d’acqua Dipartimento del territorio GREAC 1 Convegno WWF - Biodiversità nella regione dei Laghi Insubrici Lugano, 1° giugno 2012 Introduzione • Corsi d’acqua, elementi struttur-anti/-ali del paesaggio • Collegamenti privilegiati • Ambienti naturali • Luoghi di svago • Acqua e civiltà: convivenza necessaria, non priva di conflitti Cantone Ticino Ufficio dei corsi d’acqua Dipartimento del territorio GREAC 2 Convegno WWF - Biodiversità nella regione dei Laghi Insubrici Lugano, 1° giugno 2012 Indice • Le esigenze: sicurezza, ambiente e fruibilità • Rivitalizzazione e ricupero delle acque - Pianificazione strategica • Biodiversità e rete idrica • Il programma di rivitalizzazione in Ticino dal 2001 - Oggetti faro nel Sottoceneri • Conclusioni Cantone Ticino Ufficio dei corsi d’acqua Dipartimento del territorio GREAC 3 Convegno WWF - Biodiversità nella regione dei Laghi Insubrici Lugano, 1° giugno 2012 Geografia e utilizzo del territorio • 2812 km2 • 340’000 abitanti • > 7’000 ab./km2 a Massagno • < 20 ab./km2 nelle valli del Sopraceneri • Luganese e Mendrisiotto: 60%della popolazione in 15% del territorio Cantone Ticino Ufficio dei corsi d’acqua Dipartimento del territorio GREAC 4 Convegno WWF - Biodiversità nella regione dei Laghi Insubrici Lugano, 1° giugno 2012 Patrimonio naturale • 50 golene protette: 30 oggetti nazionali -

PANNELLO Di CONTROLLO Sullo Stato E Sull'evoluzione Delle Acque Del Lago Di Lugano

PANNELLO di CONTROLLO Sullo stato e sull'evoluzione delle acque del Lago di Lugano Il documento è stato redatto a cura del Segretariato Tecnico della CIPAIS ANNO 2018 Commissione Internazionale per la Protezione delle Acque Italo – Svizzere SOMMARIO Premessa 2 L3 9: Antibiotico resistenza nei batteri lacustri 26 Il Territorio di interesse per la CIPAIS 3 L3 11: Produzione primaria 27 Il Lago di Lugano 4 L3 12: Concentrazione media di fosforo e azoto 28 Indicatori del Pannello di controllo 5 L3 13: Concentrazione dell'ossigeno di fondo 29 Quadro Ambientale del 2017: aspetti limnologici 6 Tematica: Inquinamento delle acque Quadro Ambientale del 2017: sostanze inquinanti 7 L4 1: Carico di fosforo totale e azoto totale in ingresso a lago 30 Comparto: Ambiente lacustre L4 2: Microinquinanti nell’ecosistema lacustre 31, 32 Tematica: Antropizzazione e uso del territorio e delle risorse naturali Comparto: Bacino idrografico L1 1: Prelievo ad uso potabile 8 Tematica: Antropizzazione e uso del territorio e delle risorse naturali L1 2: Zone balneabili 9 B1 1: Uso del suolo 33 L1 4: Pescato 10 B1 2: Percorribilità fluviale da parte delle specie ittiche 34 L1 5: Potenziale di valorizzazione delle rive 11, 12 Tematica: Ecologia e biodiversità Tematica: Idrologia e clima B3 1: Elementi chimico - fisici 35 L2 1: Livello lacustre 13 B3 2: Macroinvertebrati bentonici 36 L2 2: Temperatura media delle acque nello strato 0-20 m e profondo 14 Tematica: Inquinamento delle acque L2 3 Massima profondità di mescolamento 15 B4 2: Stato delle opere di risanamento -

Investigations on the Caesium–137 Household of Lake Lugano, Switzerland

Caesium–137 Household of Lake Lugano INVESTIGATIONS ON THE CAESIUM–137 HOUSEHOLD OF LAKE LUGANO, SWITZERLAND J. DRISSNER, E. KLEMT*), T. KLENK, R. MILLER, G. ZIBOLD FH Ravensburg Weingarten, University of Applied Sciences, Center of Radioecology, P. O. Box 1261, D 88241 Weingarten, Germany M. BURGER, A. JAKOB GR, AC Laboratorium Spiez, Sektion Sicherheitsfragen, Zentrale Analytik und Radiochemie, CH 3700 Spiez, Switzerland *) [email protected] SedimentCaesium–137J. Drissner, E. HouseholdKlemt, TH. of Klenk Lake et Lugano al. samples were taken from different basins of Lake Lugano, and the caesium 137 inventory and vertical distribution was measured. In all samples, a distinct maximum at a depth of 5 to 10 cm can be attributed to the 1986 Chernobyl fallout. Relatively high specific activities of 500 to 1,000 Bq/kg can still be found in the top layer of the sediment. 5 step extraction experiments on sediment samples resulted in percentages of extracted caesium which are a factor of 2 to 8 higher than those of Lake Constance, where caesium is strongly bound to illites. The activity concentration of the water of 3 main tributaries, of the outflow, and of the lake water was in the order of 5 to 10 mBq/l. 1 Introduction Lake Lugano with an area of 48.9 km2 and a mean depth of 134 m is one of the large drinking water reservoirs of southern Switzerland, in the foothills of the southern Alps. The initial fallout of Chernobyl caesium onto the lake was about 22,000 Bq/m2 [1], which is similar to the initial fallout of about 17, 000 Bq/m2 onto Lake Constance, which is located in the prealpine area of southern Germany (north of the Alps). -

Banca Raiffeisen Del Vedeggio Società Atletica Isone-Medeglia Sagra Della Staffetta Scolari 6810 Isone Classifiche Finali 23/09/2013

Società Atletica Isone-Medeglia Associazione Sportiva Ticinese Sponsor: Banca Raiffeisen del Vedeggio Società Atletica Isone-Medeglia Sagra della staffetta scolari www.saim.ch 6810 Isone Classifiche finali 23/09/2013 INDIVIDUALI Categoria Scoiattole - 2006 e dopo 1 FG Malcantone Guglielmetti Emma 2006 00:51.13 2 SFG Morbio Galli Charlotte 2006 3 FG Malcantone Schenk Sofia 2006 4 SAM Massagno Gomez de Zamora Lotta 2006 5 SAIM Isone-Medeglia Della Pietra Lara 2007 6 USC Capriaschese Fovini Sofia 2006 7 SAM Massagno Zanetti Matilde 2007 8 USC Capriaschese Quittero Linda 2006 9 SAM Massagno Jegatheesan Shanika 2006 10 USC Capriaschese Stampanoni Selina 2006 11 FG Malcantone Hösli Lisa 2008 12 USC Capriaschese Fiala Letizia 2006 13 USC Capriaschese Panizza Viola 2006 14 USC Capriaschese Panizza Zoe 2007 15 SVAM Muggio Mordasini Nicole 2008 16 USC Capriaschese Stampanoni Olivia 2008 17 SVAM Muggio Wildi Chiara 2008 18 FG Malcantone Baggi Anna 2008 19 SAIM Isone-Medeglia Rossi Melissa 2008 2/8 Società Atletica Isone-Medeglia Sagra della staffetta scolari www.saim.ch 6810 Isone Classifiche finali 23/09/2013 Categoria Scoiattoli - 2006 e dopo 1 SFG Morbio Meroni Aaron 2006 00:47.25 2 SAL Lugano Fattorini Nicola 2006 3 VIRTUS Locarno Maggetti Elia 2006 4 SAL Lugano Bernaschina Luca 2006 5 SAM Massagno Marti Julian 2006 6 SAIM Isone-Medeglia Müller Sedric 2007 7 SAIM Isone-Medeglia Scerpella Enea 2006 8 SAM Massagno Vignutelli Daniele 2007 9 USC Capriaschese Battaini Samuele 2006 10 SAM Massagno Gaggini Nicola 2006 11 SAIM Isone-Medeglia Beltrami -

Aerodrome Chart 18 NOV 2010

2010-10-19-lsza ad 2.24.1-1-CH1903.ai 19.10.2010 09:18:35 18 NOV 2010 AIP SWITZERLAND LSZA AD 2.24.1 - 1 Aerodrome Chart 18 NOV 2010 WGS-84 ELEV ft 008° 55’ ARP 46° 00’ 13” N / 008° 54’ 37’’ E 915 01 45° 59’ 58” N / 008° 54’ 30’’ E 896 N THR 19 46° 00’ 30” N / 008° 54’ 45’’ E 915 RWY LGT ALS RTHL RTIL VASIS RTZL RCLL REDL YCZ RENL 10 ft AGL PAPI 4.17° (3 m) MEHT 7.50 m 01 - - 450 m PAPI 6.00° MEHT 15.85 m SALS LIH 360 m RLLS* SALS 19 PAPI 4.17° - 450 m 360 m MEHT 7.50 m LIH Turn pad Vedeggio *RLLS follows circling Charlie track RENL TWY LGT EDGE TWY L, M, and N RTHL 19 RTIL 10 ft AGL (3 m) YCZ 450 m PAPI 4.17° HLDG POINT Z Z ACFT PRKG LSZA AD 2.24.2-1 GRASS PRKG ZULU HLDG POINT N 92 ft AGL (28 m) HEL H 4 N PRKG H 3 H 83 ft AGL 2 H (25 m) 1 ASPH 1350 x 30 m Hangar L H MAINT AIRPORT BDRY 83 ft AGL Surface Hangar (25 m) L APRON BDRY Apron ASPH HLDG POINT L TWY ASPH / GRASS MET HLDG POINT M AIS TWR M For steep APCH PROC only C HLDG POINT A 40 ft AGL HLDG POINT S PAPI (12 m) 6° S 33 ft AGL (10 m) GP / DME PAPI YCZ 450 m 4.17° GRASS PRKG SIERRA 01 50 ft AGL 46° (15 m) 46° RTHL 00’ 00’ RTIL RENL Vedeggio CWY 60 x 150 m 1:7500 Public road 100 0 100 200 300 400 m COR: RWY LGT, ALS, AD BDRY, Layout 008° 55’ SKYGUIDE, CH-8602 WANGEN BEI DUBENDORF AMDT 012 2010 18 NOV 2010 LSZA AD 2.24.1 - 2 AIP SWITZERLAND 18 NOV 2010 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK AMDT 012 2010 SKYGUIDE, CH-8602 WANGEN BEI DUBENDORF 16 JUL 2009 AIP SWITZERLAND LSZA AD 2.24.10 - 1 16 JUL 2009 SKYGUIDE, CH-8602 WANGEN BEI DUBENDORF REISSUE 2009 16 JUL 2009 LSZA AD 2.24.10 - 2 -

Commissariato Italiano Per La Convenzione Italo-Svizzera Sulla Pesca

SEGRETERIA E RECAPITO CORRISPONDENZA Commissariato italiano COMMISSARIATO ITALIANO PER LA PESCA c/o CNR Istituto di Ricerca Sulle Acque via Tonolli 50 28922 Verbania Pallanza per la Convenzione tel. 0323 518327 fax 0323 55651 posta certificata [email protected] italo-svizzera sulla pesca e-mail segreteria [email protected] Codice Fiscale 93007650034 DATA N. Argomento ordinanze pag. 14/06/21 03/21 Pescate di sfoltimento di agone nel Lago Maggiore ….………….………….………….………….……. 1 03/06/21 02/21 Proroga scadenza dell’ordinanza n. 02/15 ……….………….………….………….………….…………. 2 11/01/21 01/21 Libretto segna pesci della pesca dilettantistica nelle acque lombarde soggette alla CISPP ….…..… 3 23/12/19 03/19 Libretto segna catture della pesca professionale nelle acque lacustri lombarde della CISPP ……… 4 16/12/19 02/19 Divieti di pesca allo sbocco e imbocco del F. Tresa a Lavena Ponte Tresa ………………………….. 5 21/12/18 03/18 Nuovo Regolamento di Applicazione della Convenzione (R.d.A . 2019)………………………………. 6 15/06/16 01/16 Orari della pesca professionale nelle acque italiane del Lago di Lugano………………………………. 7 08/02/16 C1/16 Impiego delle reti volanti nel Lago Maggiore ……………………………………………..………………. 8 10/11/15 14/15 Protezione popolamenti coregoni, lucioperca, persico e trota nelle acque italiane del L.Maggiore … 9 01/01/15 02/15 Protezione della fauna ittica alla foce dei principali tributari dei laghi Maggiore e di Lugano ……….. 10 01/01/15 03/15 Divieto di pesca dell’agone nelle acque italiane del Lago Maggiore ……………………………………. 11 01/01/15 05/15 Orari della pesca con attrezzi professionali nelle acque italiane del Lago Maggiore ......................... -

Piano Zone Biglietti E Abbonamenti 2021

Comunità tariffale Arcobaleno – Piano delle zone arcobaleno.ch – [email protected] per il passo per Geirett/Luzzone per Göschenen - Erstfeld del Lucomagno Predelp Carì per Thusis - Coira per il passo S. Gottardo Altanca Campo (Blenio) S. Bernardino (Paese) Lurengo Osco Campello Quinto Ghirone 251 Airolo Mairengo 243 Pian S. Giacomo Bedretto Fontana Varenzo 241 Olivone Tortengo Calpiogna Mesocco per il passo All’Acqua Piotta Ambrì Tengia 25 della Novena Aquila 245 244 Fiesso Rossura Ponto Soazza Nante Rodi Polmengo Valentino 24 Dangio per Arth-Goldau - Zurigo/Lucerna Fusio Prato Faido 250 (Leventina) 242 Castro 331 33 Piano Chiggiogna Torre Cabbiolo Mogno 240 Augio Rossa S. Carlo di Peccia Dalpe Prugiasco Lostallo 332 Peccia Lottigna Lavorgo 222 Sorte Menzonio Broglio Sornico Sonogno Calonico 23 S. Domenica Prato Leontica Roseto 330 Cama Brontallo 230 Acquarossa 212 Frasco Corzoneso Cauco Foroglio Nivo Giornico Verdabbio Mondada Cavergno 326 Dongio 231 S. Maria Leggia Bignasco Bosco Gurin Gerra (Verz.) Chironico Ludiano Motto (Blenio) 221 322 Sobrio Selma 32 Semione Malvaglia 22 Grono Collinasca Someo Bodio Arvigo Cevio Brione (Verz.) Buseno Personico Pollegio Loderio Cerentino Linescio Riveo Giumaglio Roveredo (GR) Coglio Campo (V.Mag.) 325 Osogna 213 320 Biasca 21 Lodano Lavertezzo 220 Cresciano S. Vittore Cimalmotto 324 Maggia Iragna Moghegno Lodrino Claro 210 Lumino Vergeletto Gresso Aurigeno Gordevio Corippo Vogorno Berzona (Verzasca) Prosito 312 Preonzo 323 31 311 Castione Comologno Russo Berzona Cresmino Avegno Mergoscia Contra Gordemo Gnosca Ponte Locarno Gorduno Spruga Crana Mosogno Loco Brolla Orselina 20 Arbedo Verscio Monti Medoscio Carasso S. Martino Brione Bellinzona Intragna Tegna Gerra Camedo Borgnone Verdasio Minusio s. -

Commissione Internazionale Per La Protezione Delle Acque Italo-Svizzere

ISSN: 1013-8080 Commissione Internazionale per la protezione delle acque italo-svizzere Ricerche sull'evoluzione del Lago di Lugano Aspetti limnologici Programma quinquennale 1998-2002 Campagna 2002 e Rapporto quinquennale 1998-2002 Ufficio Protezione e Depurazione Acque Sezione Protezione Aria, Acqua e Suolo Dipartimento del Territorio - Cantone Ticino I dati riportati nel presente volume possono essere utilizzati purchè se ne citi la fonte come segue: Ufficio Protezione e Depurazione Acque (UPDA), 2003: “Ricerche sull’evoluzione del Lago di Lugano. Aspetti limnologici. Programma quinquennale 1998-2002. Campagna 2002 e rapporto quinquennale 1998-2002.” Commissione Internazionale per la Protezione delle Acque Italo-Svizzere (Ed.); 110 pp. 3 R I A S S U N T O Questo volume presenta i dati limnologici sul Lago di Lugano raccolti dall'Ufficio Protezione e Depurazione Acque (UPDA) del Cantone Ticino durante la campagna 2002, nell’ambito dell’attività di ricerca della Commissione Internazionale per la Protezione delle Acque Italo-Svizzere svolta a partire dal 1978. Trattandosi dell'ultimo rapporto del quinquennio 1998-2002 è stato inoltre presentato e discusso l'andamento limnologico del lago sul lungo periodo. Le informazioni ottenute nel corso del 2002 permettono di aggiornare le serie storiche disponibili per i principali parametri limnologici, e di descrivere le tendenze evolutive del Lago in relazione agli interventi di depurazione sinora realizzati. Durante l’anno è proseguita l'analisi dettagliata dei carichi esterni di fosforo ai due bacini principali, in modo da verificare in quale misura le opere di risanamento contribuiscano al recupero del corpo idrico. La progressiva riduzione delle concentrazioni di fosforo riscontrata nell’ultimo decennio è proseguita nel bacino sud, mentre si è arrestata all'interno dello strato 0-100 m del bacino nord. -

Afternoon Drop-Off 2021-2022

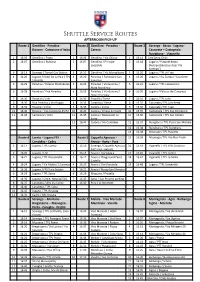

Shuttle Service Routes AFTERNOON PICK-UP Route 1 Gentilino - Paradiso - Route 2 Gentilino - Paradiso - Route 3 Sorengo - Besso - Lugano - Bissone - Campione d’Italia Carona Cassarate – Castagnola - Ruvigliana - Viganello 1 16.05 Gentilino / Posta 1 16.06 Gentilino / Via Chioso 1 16.14 Sant’Anna Clinic 2 16.07 Gentilino / Rubiana 2 16.07 Gentilino / Principe 2 16.18 Lugano / Piazzale Besso Leopoldo (Autopostale) bus stop ‘Via Sorengo’) 3 16.13 Sorengo / Tamoil Gas Station 3 16.10 Gentilino / Via Montalbano 3 16.20 Lugano / TPL Ai Frati 4 16.20 Lugano / Hotel De La Paix / TPL 4 16.20 Paradiso / Funicolare San 4 16.20 Lugano / Via Zurigo / ‘Casaforte’ S.Birgitta Salvatore 5 16.25 Paradiso / Palazzo Mantegazza 5 16.22 Paradiso / Via Guidino / 5 16:22 Lugano / TPL Cappuccine Nizza Residence 6 16.28 Paradiso / Riva Paradiso 6 16.23 Paradiso / Via Guidino / 6 16.30 Lugano / Palazzo dei Congressi Hotel The View 7 16.30 Paradiso / Lido 7 16.30 Pazzallo / Paese 7 16:31 Lugano / TPL Lido 8 16.30 Riva Paradiso / Via Boggia 8 16.33 Carabbia / Paese 8 16.32 Cassarate / TPL Lanchetta 9 16.35 Bissone / Circle 9 16.35 Carona / Ciona 9 16.33 Cassarate / TPL Lago 10 16.40 Bissone / Via Campione 45/55 10 16.40 Carona / Chiesa dei Santi 10 16.35 Castagnola / TPL San Domenico 11 16.43 Campione / Arco 11 16.45 Carona / Restaurant La 11 16.36 Castagnola / TPL San Giorgio Sosta 12 16:47 Carona / Via Colombei 12 16.37 Ruvigliana / TPL Parco San Michele 13 16.38 Ruvigliana / TPL Suvigliana 14 16:38 Albonago / TPL Ruscello Route 4 Loreto - Lugano FFS - Route 5 Cappella -

Arcobaleno. La Scelta Giusta Che Ti Premia

Arcobaleno. La scelta giusta che ti premia. Edizione 2018/19 arcobalenopremia.ch 48 offerte annuali Le offerte dei nostri partner In qualità di abbonati annuali Arcobaleno potete beneficiare in qualsiasi momento dell’anno delle offerte pensate per voi dai nostri partner. Le convenzioni sono suddivise in quattro aree tematiche: Formazione e cultura Shopping e servizi Sport e benessere Viaggi e tempo libero Maggiori informazioni sulle singole offerte sono riportate nelle pagine dedicate ai partner e sul sito arcobalenopremia.ch In aggiunta alle convenzioni quadro, il programma fedeltà propone ogni tre mesi: Offerte stagionali Concorso a premi Le offerte stagionali possono essere visionate sul sito e tramite la nostra newsletter. La newsletter elettronica del programma fedeltà Per essere sempre informati su novità e proposte è sufficiente iscriversi alla newsletter elettronica del programma fedeltà. La newsletter è spedita, di regola, quattro volte all’anno, in corrispondenza del lancio delle offerte stagionali. Visita arcobaleno.ch/newsletter Edizione 2018/19. Con riserva di modifica. I premi e i benefici connessi al programma fedeltà non sono convertibili in denaro. La CTA non è responsabile della qualità delle prestazioni erogate dai partner. Non si tiene corrispondenza in merito ai concorsi promossi in abbinamento al programma fedeltà. Condizioni di utilizzo consultabili su arcobalenopremia.ch. Cartoleria Libreria ABC . Biasca 5% di sconto sui libri e 10% su articoli regalo e ufficio. L’offerta non è cumulabile con altre promozioni particolari. Cinema Teatro . Chiasso Fino al 10% di sconto sugli abbonamenti e fino al 15% sui biglietti. Per beneficiare dello sconto gli abbonati devono presentare l’abbonamento ed il tagliando scaricabile sul sito Arcobaleno. -

Linee Trasporti Pubblici Luganesi SA Valide a Partire Dal 13.12.2020

Linee Trasporti Pubblici Luganesi SA Valide a partire dal 13.12.2020 Giubiasco Bellinzona Origlio- Sureggio- Carnago- Manno- Piano Stampa Locarno Tesserete Tesserete Tesserete Bioggio Capolinea Basilea-Zurigo a Lamone Farer Cadempino Comano Canobbio Stazione Ganna lio Mag te on le P al V Manno di Uovo di Manno 19 Cadempino Municipio Canobbio Cadempino Comano Ronchetto Mercato Resega Studio TV Cureglia Rotonda Comano cio Rotonda c de Resega er Ghia Trevano ta ce V is o Centro Studi P Cr Villa 7 Negroni 19 a ic Resega Term Vezia Paese o Lugano Cornaredo ared i/Corn an i Stadio Est a Ci Cureggia Vi tan Pregassona ren Paese ia B Piazza di Giro Vignola V na ami tr Villa Recreatio Bel Cà Rezzonico a Vi a Viganello za S. Siro lla an sa Seren Vi st Ospedale Vignola Scuole Ca Co Civico Molino Nuovo 2 ovo h i sc ch Scuole a Nu tà ri n z o si F Piazza Molino Nuovo az in er x Ro o Pi l v a sc Praccio Molino Nuovo 2 i ai Mo Un ia M Bo V al al Sole Sassa Via Santa Lucia Zurigo Sacro ta Brè Pianazzo Vicolo Cuore San vecchio a le Paese Paese l Albonago o Autosilo ia edano ag ez ia Balestra Corsolv Ospal Paese ldes Vergiò E It A Genzana - to u o A o a i que Vie l in Si C io Via Balestr Rad Gradinata S. Anton udio Lugano St lao Suvigliana co i Centro o t Scuole Funicolare di ri Ni Cassarate to S. -

Relazione Porlezza Torrenti

GEOPLANET INDICE 1. PREMESSA__________________________________________________________________ 2 1. INQUADRAMENTO GEOGRAFICO _________________________________________ 7 2. INQUADRAMENTO GEOLOGICO __________________________________________ 8 2.1 CENNI PALEOGEOGRAFICI ___________________________________________________ 8 3. COMMENTO ALLA CARTA GEOLOGICO-STRUTTURALE _____________________ 9 3.1 – CARATTERI GEOMORFOLOGICI E GEOLOGICI _________________________________ 9 3.2 – CARATTERI LITOLOGICI _____________________________________________________ 11 3.2.1 Depositi superficiali ___________________________________________________________________ 11 3.2.2 Substrato roccioso ____________________________________________________________________ 13 4. ASPETTI PEDOLOGICI __________________________________________________ 21 5. OSSERVAZIONI CLIMATOLOGICHE ______________________________________ 21 INQUADRAMENTO METEO-CLIMATICO ___________________________________________ 21 5.1.1Temperatura atmosferica ________________________________________________________________ 21 5.1.2 Radiazione solare globale _______________________________________________________________ 22 5.1.3 Precipitazioni _________________________________________________________________________ 23 5.1.4 Intensità dei venti ______________________________________________________________________ 24 6. CARATTERISTICHE METEOROLOGICHE DELL'AREALE LACUSTRE 1998-2007 25 7. REGIME DEL LIVELLO LACUSTRE _______________________________________ 27 7.1 Regime del livello lacustre 1930-1997 _________________________________________________