Experiencing Russian Food

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classics : Alwaysavailable Starters

CLASSICS: ALWAYS AVAILABLE DESTINATION MENU STARTERS Bergen Salmon Gravlax beet marinated, cured salmon Malossol Paddlefish Caviar (market price) Lamb Farikal Blini; traditional condiments lamb brisket & green cabbage stew in lamb consommé Tiger Prawns Frognerseteren’s Apple Cake poached & chilled, cocktail sauce puff pastry layered with spiced apple jam; whipped cream & berries Caesar Salad romaine, anchovies, parmesan, garlic croutons, traditional Caesar dressing DINNER MENU MAIN COURSES STARTERS Angus New York Strip Steak (9 oz) Caribbean Senses grilled to order; steak fries, beurre maître d’hôtel marinated exotic fruit with Cointreau Chairman’s Choice: Poached Norwegian Salmon Prosciutto & Melon fresh pickled cucumber and boiled potatoes aragula & cherry tomato salad Roasted Free Range Poulet de Bresse Crème of Halibut chef’s favorite mash, au jus saffron rice & julienne leeks SIDES Endive & Williams Pear Salad celery, almonds; grainy mustard & apple cider vinaigrette Steamed Vegetables; Green Beans; Baked Potato; Mashed Potato; Creamed Spinach; Rice Pilaf MAIN COURSES Lumache con Carciofi e Pomodoro Secco DESSERTS shell pasta with artichokes, guianciale (pork) & sundried tomato Crème Brûlée Grilled Swordfish Steak with Tomato Relish Bourbon vanilla on basil crusted fingerling potato; bois boudran sauce New York Cheesecake Cornish Game Hen strawberry, raspberry, blueberry raspberry sauce; chanterelle mushrooms, farro risotto Fromagerie Braised Beef Ribs homemade chutney, crackers, grapes & baguette peanut sauce & coconut; steamed rice Fresh Fruit Plate melon, pineapple & berries DESSERTS Today’s Ice Cream Selection or Sorbet Chocolate Volcano lemon curd, poppy seed tuile Vanilla Risotto SOMMELIER’ S RECOMMENDATION silken tofu, vanilla bean Wine Name $36 Wine Name $32 Country Country VEGETARIAN HIGHLIGHTS Brie in Crispy Phyllo candied pecan & cranberry compote Gluten‐free bread available upon request. -

Hand Made. Hand Approved

// Class Schedule Happenings FEBRUARY 2020 cooksofcrocushill.com Guest Chef WHAT CHOUX TALKING ABOUT?! CROISSANTS 101 Ryan Siess Randi Madden SW SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 8, 10 AM – 12:30 PM, $80 MPLS SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 23, 11 AM – 1:30 PM, $85 Cooks has been hosting world-renowned chefs in the Twin Cities for more than 30 years. Luminaries such as Marcus Samuelsson, Thomas Keller Pronounced "pot ah SHOO" (à vos souhaits!), French specialty pâte à In Paris, you can't walk two blocks without coming across a small and Sean Brock — not to mention local all-stars like Gavin Kaysen, Paul choux might mean "cabbage paste," but it's got nothing to do with the boulangerie pulling fresh-baked croissants out of an oven. Around Berglund and Ann Kim — regularly bring their skills and passion to our crunchy vegetable. Instead, it's a versatile dough that forms the base here, not so much. In this hands-on class, Chef Randi will show you kitchens. for some of the dreamiest, must-have pastries on the planet. Think how to make light, flaky, buttery croissant dough, roll it out and create cream puffs, éclairs and profiteroles. (If that's what cabbages tasted beautiful pastries that you don't need a passport to get! LYNNE AND PAUL POP-UP DINNER like, we'd all be farmers.) In this hands-on class, Chef Ryan reveals the Paul Berglund and Lynne Rossetto Kasper secrets of these divine desserts. Traditional Croissant; Pain au Chocolat; Sweet Ricotta Pinwheels; Two Savory Croissants. $ SP FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 7, 6:30 PM – 8:30 PM, 90 Chocolate-Dipped Vanilla Pastry Cream-Filled Éclairs; Crème Chantilly Cream Puffs; Fresh Herb and Gruyère Gnocchi with Gorgonzola Cream SP SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 8, 6:30 PM – 8:30 PM, $90 PARISIAN SWEET PASTRIES Sauce. -

Georgia, Armenia & Azerbaijan

Land Program Rate: $6,195 (per person based on double occupancy) Single Supplement: $1,095 Included: All accommodation, hotel taxes • Meals per itinerary (B=breakfast, L=lunch, D=dinner) • Arrival/departure transfers for pas- sengers arriving/departing on scheduled start/ end days • All land transportation per itinerary including private motor coach throughout the itinerary • Internal airfare between Baku and Tbilisi • Study leader and pre-departure education materials • Special cultural events and extensive sightseeing, includ- ing entrance fees • Welcome and farewell dinners • Services of a tour manager throughout the land program • Gratuities to tour manager, guides and drivers • Comprehensive pre-departure packet Not Included: Travel insurance • Round trip airfare between Baku/Yerevan and USA. Our tour operator MIR Corporation can assist with reservations. • Passport and visa fees • Meals not specified as included in the itinerary • Personal items such as telephone calls, alcohol, laun- dry, excess baggage fees Air Arrangements: Program rates do not include international airfare from/to USA. Because there are a number of flight options available, there is no group flight for this program. Informa- tion on a recommended flight itinerary will be sent by our tour operator upon confirmation. What to Expect: This trip is moderately active due to the substantial distances covered and Club of California The Commonwealth St 555 Post CA 94102 San Francisco, the extensive walking and stair climbing required; parts of the tour will not always be wheelchair - accessible. To reap the full rewards of this adventure, travelers must be able to walk at least a mile a day (with or without the assistance of a cane) and stand for an extended period of time during walking tours and museum visits. -

A Taste of Teaneck

.."' Ill • Ill INTRODUCTION In honor of our centennial year by Dorothy Belle Pollack A cookbook is presented here We offer you this recipe book Pl Whether or not you know how to cook Well, here we are, with recipes! Some are simple some are not Have fun; enjoy! We aim to please. Some are cold and some are hot If you love to eat or want to diet We've gathered for you many a dish, The least you can do, my dears, is try it. - From meats and veggies to salads and fish. Lillian D. Krugman - And you will find a true variety; - So cook and eat unto satiety! - - - Printed in U.S.A. by flarecorp. 2884 nostrand avenue • brooklyn, new york 11229 (718) 258-8860 Fax (718) 252-5568 • • SUBSTITUTIONS AND EQUIVALENTS When A Recipe Calls For You Will Need 2 Tbsps. fat 1 oz. 1 cup fat 112 lb. - 2 cups fat 1 lb. 2 cups or 4 sticks butter 1 lb. 2 cups cottage cheese 1 lb. 2 cups whipped cream 1 cup heavy sweet cream 3 cups whipped cream 1 cup evaporated milk - 4 cups shredded American Cheese 1 lb. Table 1 cup crumbled Blue cheese V4 lb. 1 cup egg whites 8-10 whites of 1 cup egg yolks 12-14 yolks - 2 cups sugar 1 lb. Contents 21/2 cups packed brown sugar 1 lb. 3112" cups powdered sugar 1 lb. 4 cups sifted-all purpose flour 1 lb. 4112 cups sifted cake flour 1 lb. - Appetizers ..... .... 1 3% cups unsifted whole wheat flour 1 lb. -

Bakery and Confectionary HM-302 UNIT: 01 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND of BAKING

Bakery and Confectionary HM-302 UNIT: 01 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF BAKING STRUCTURE 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Objective 1.3 Historical Background of Baking 1.4 Introduction to Large, Small Equipments and Tools 1.5 Wheat 1.5.1 Structure of Wheat 1.5.2 Types of Flour 1.5.3 Composition Of Flour 1.5.4 WAP of Flour 1.5.5 Milling of Wheat 1.5.6 Differences Between Semolina, Whole Wheat Flour And Refined Flour 1.5.7 Flour Testing 1.6 Summary 1.7 Glossary 1.8 Reference/Bibliography 1.9 Terminal Questions 1.1 INTRODUCTION BREAD!!!!…….A word of many meanings, a symbol of giving, one food that is common to so many countries….but what really is bread ????. Bread is served in various forms with any meal of the day. It is eaten as a snack, and used as an ingredient in other culinary preparations, such as sandwiches, and fried items coated in bread crumbs to prevent sticking. It forms the bland main component of bread pudding, as well as of stuffing designed to fill cavities or retain juices that otherwise might drip out. Bread has a social and emotional significance beyond its importance as nourishment. It plays essential roles in religious rituals and secular culture. Its prominence in daily life is reflected in language, where it appears in proverbs, colloquial expressions ("He stole the bread from my mouth"), in prayer ("Give us this day our daily bread") and in the etymology of words, such as "companion" (from Latin comes "with" + panis "bread"). 1.2 OBJECTIVE The Objective of this unit is to provide: 1. -

Minnesota Cottage Foods Law

MINNESOTA COTTAGE FOODS LAW Minnesota Statute 28A.152 Cottage Foods Exemption NON-POTENTIALLY HAZARDOUS FOODS FACT SHEET As of July 1, 2015, individuals can sell non-potentially hazardous (NPH) foods made in their home kitchens, without a license (Minnesota Statute 28A.152). Non-potentially hazardous (NPH) foods are foods that do not support the rapid growth of bacteria that would make people sick when held outside of refrigerated temperatures. These are the types of foods the Minnesota Cottage Foods Law exempt from licensing. MFMA has worked with the Minnesota Department of Agriculture, the Minnesota Department of Health, and the University of Minnesota Extension Food Safety Team to compile this list. If a food item is not on this list, contact your local Minnesota Department of Agriculture Food Inspector for more details. To find the contact information for your local MDA food inspector, call (651) 201-6027 or email [email protected]. LIST UPDATES This list will be reviewed periodically and updated as needed. When the list is updated, the revision date for this document will be changed and MFMA will send an email to everyone on our contacts list. To ensure that you receive these updates, please go to MFMA’s website www.mfma.org and sign up for our elist. This list was last updated: December 20. 2019 USING THIS LIST For ease of use, this list is divided into Food Type categories. Each category lists three options: Allowed Foods, Not Allowed Foods, and Exceptions. All foods listed in the “Exceptions” column need extra information and we strongly recommend you contact the MDA to discuss the potential risks associated with the “Exceptions” foods. -

The Importance of the Role of Local Food in Georgian Tourism

European Scientific Journal December 2015 /SPECIAL/ edition Vol.2 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 THE IMPORTANCE OF THE ROLE OF LOCAL FOOD IN GEORGIAN TOURISM Maia Meladze, Associate Professor Grigol Robakidze University, Tbilisi, Georgia Abstract The top three activities undertaken in Georgia by international travelers are: rest and relaxation (36%), tasting Georgian dishes (35%), exploring Georgian nature/landscape (35%), etc. Gastronomy has become one of the most important parts of a tourism market. Georgia is a unique country – as a homeland of wine and a country which is distinctive for its plenty of ethnographic regions. Each historical-ethnographic region had its own natural and agricultural specificity, which led to the peculiarity of the ethnic group feeding. A great Majority of foreign tourists, who tries Georgian traditional dish for the first time, declares about its best taste and scent at once. Georgia's traditional winemaking method of fermenting grapes in earthenware, egg-shaped vessels has been added to the world heritage list of the UNESCO. Georgian gastronomic diversity is a great resource for tourism development in the country. Friendliness and goodwill of a tourist greatly depends on the dishes and beverages they are offered. Keywords: Georgia, Tourism, Gastronomy, Food, Traditional dishes Introduction For many of the world’s billions of tourists to enjoy tried and tested recipes, cuisine, gastronomy has become a central part of the tourism experience. In addition, tasting local foods has become an important way to enjoy the local culture. Local food at a destination can bring tourists physical, cultural, social and prestige experience. Food and its related tourist activities have been described into a new category of tourism called food tourism in which the motivation for traveling is to obtain special experiences from food. -

Stall 8 P-Ifee. Pla.Ce. Seattle., Wcuhington 9SI01 CATHY CONNER 624-2222

Stall 8 P-ifee. Pla.ce. Seattle., Wcuhington 9SI01 CATHY CONNER 624-2222 CROISSANTS Ham and Cheese Pain Aux Raisin Oreitlon - Croisant dough with apricot halves and pastry cream Almond Croissants BRIOCHE Small a tete Large a tete Pain aux Raisins Loaf Loaf with Raisins Loaf with cinnamon sugar, brown sugar, walnuts Swiss Brioche - Brioche cake with candied fruits soaked in rum and glaced with glace a l'cau flavored with rum. Brioche cinnamon rolls BREAP French Baguette - short. TARTES Apple - Fresh apple with pastry cream on pate Feuilletfe. Amandines - fruits with almond cream in light buttery pastry - • Apricot • Pear • Peach • Plum Lemon Tarte - lemon butter filling in Pate Sucree shells covered with osettes of meringue. Linzer Tarte - Linzer tarte shell with rasberry jam. Conversation - Almond filled tartes baked with sliced almonds a Glace Royale. Tarte Tatin - Carmalized apple baked with puff paste. Cherry and Pineapple tartes baked with Pate Fenilletee. 7 - POMMES GAl/ROCf/E Half an apple cored and filled with raisins and rum flavored pastry cream, wrapped in puff pastry. CHAUSSON AUX POMMES [loJiae OK mall) Apple puree wrapped in puff paste, similar to a turnover. PITfilt/IER Band or round. Puff paste filled with almond cream and topped with almonds. PALMIERS Folded twice or four times, large or small. miLE HUJLLES Layers of puff pastry and Kirsh flavored pastry cream. GlSced with fondant and chocolate or just powdered sugar. CONVERSATIONS Almond cream tartes covered and baked with sliced almonds or Glace Royal. PARIS BREST Choux Paste with sliced almonds, shaped in ring, cut in half and garnished with Praline cream. -

Einstieg Dänisch, ISBN 978-3-19-005417-6, © Hueber Verlag En Kop Kaffe 4

4 Pause mit Smörrebröd varme drikke Sandra und Bo konnten noch einen der Tische draußen ergattern. (warme Getränke) Fast wie Amsterdam, denkt Sandra mit Blick auf den Kanal. Doch en cappuccino die maritime Atmosphäre muss noch etwas warten. Zunächst stu- (ein Cappuccino) en espresso diert Sandra die Karte. (ein Espresso) Bei den Getränken fällt ihr die Entscheidung leicht: Jeg skal have en kop kakao en kop kaffe (Ich nehme eine Tasse Kaffee). Mit dem Essen ist San- (eine Tasse Kakao) dra noch unentschieden: Måske et stykke kage (Vielleicht ein en kop te Stück Kuchen). Bo schlägt et stykke smørrebrød (ein Stück Smör- (eine Tasse Tee) rebröd) vor. Diese kunstvoll belegten Brote sind für Dänemark-Be- kolde drikke sucher ein Muss, meint er. Sandra lässt sich gerne überzeugen: Det (kalte Getränke) lyder godt (Das klingt gut). Dazu passt dann aber der Kaffee nicht en danskvand mehr recht: Så tager jeg hellere en øl (Dann nehme ich lieber ein (ein Mineralwasser) Bier). en sodavand (eine Limonade) Wie in den meisten dänischen Cafés gilt auch hier Selbstbedie- en cola nung. Am Tresen kommt Sandra Bo zuvor. Sie lässt sich keine Ge- (eine Cola) legenheit entgehen, ihr Dänisch zu praktizieren. Vi vil gerne have en appelsinjuice to stykker smørrebrød med leverpostej og bacon (Wir hätten gern (ein Orangensaft) zwei Stücke Smörrebröd mit Leberpastete und Bacon). Und sogar en fadøl (ein Fassbier) die unerwartete Gegenfrage nach der Biermarke meistert sie mit et glas vin links. Ganz besonders freut sie sich, dass sie auch noch den Preis (ein Glas Wein) versteht: Det bliver hundrede og fjorten kroner (Das macht 114 Kronen). -

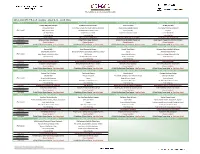

March 2020 MTS P.E.A.S.E. Academy

This institution is an equal opportunity provider March 2020 MTS P.E.A.S.E. Academy - Grade 9-12 - Lunch Menu Week 1 Monday, March 2, 2020 Tuesday, March 3, 2020 Wednesday, March 4, 2020 Thursday, March 5, 2020 Cowboy BBQ Cheeseburger Southwest Chicken Nachos Arroz Con Pollo All Beef Hot Dog Doritos Cool Ranch Corn Chips, Lettuce, Chz, Diced Tomatoes & Cilantro Mised Greens Salad & Dressing Hot Dog Bun, Ketchup & Mustard Hot Lunch Baby Carrots & Dip Cholula Hot Sauce & Sour Cream Fruit of the Day Funyuns CKC Baked Beans Ranchero's Corn Salad Chocolate Caramel Chex Mix Carrot Slims & Dip Fruit of the Day Fruit of the Day Fruit of the Day Veg Lunch Garden Burger Cheese Lasagna w/Marinara Veggie Pizza Pack (Like a Lunchable) Egg & Cheese Biscuit Sandwich Cold Lunch Turkey on Whole Wheat Bread Grilled Chicken Bagel Sandwich Grilled Chicken & Cheddar Cheese Bun Greek Yogurt, Cheese Stick & Animal Crackers Veg Cold Lunch Cheese Sandwich Cheese Sandwich Cheese Sandwich Cheese Sandwich Deli Salad Grilled Chicken Caesar Salad or Veg Caesar Salad Grilled Asian Chicken Salad or Veg Asian Salad Grilled Chix Southwest Taco Salad or Veg Taco Salad Grilled Chicken Power Salad or Veg Power Salad Week 2 Monday, March 9, 2020 Tuesday, March 10, 2020 Wednesday, March 11, 2020 Thursday, March 12, 2020 Korean BBQ Juicy Mozzarella Burger French Toast Sticks Delicious Spicy Meatballs & Sauce Steamed Seasoned Rice WG Bun &Tomato & Leaf Lettuce w/Ketchup & Mayo Syrup Steamed Seasoned Rice Hot Lunch Baby Carrots, Celery Sticks & Dip Hot Cheetos Crispy Cubes & -

Kayem Choice Beef Pot Roast Recipes

KAYEM SLOW COOKED CHOICE BEEF POT ROAST RREECCIIPPEE GGUUIIDDEE AU JUS SLOW COOKED FOR HOURS,-EXTRA TENDER GLUTEN FREE ALL NATURAL SPICES NO MSG SHEPARD PIE WITH POT ROAST INGREDIENTS 7.75 pounds Kayem Slow Cooked Choice Beef Pot Roast, (drain au jus, reserve) 1/3 cup wondra 1 cup water 14 ounces creamed corn 2 pounds mashed potatoes 3 tablespoons unsalted butter 12 teaspoon paprika (preferably smoky paprika) DIRECTIONS Pre-heat oven to 350 F Cut the pot roast into 1 1/2" strips lengthwise. Trim away any fat or connective tissues. Hand shred the beef into a baking dish. (Meat breaks apart very easily since it is already slow roasted). Using a small bowl, mix the Wondra into the water, stir well. Transfer the reserved au jus to a medium sauce pan over medium high heat, and wisk in the flour/water mixture. Bring to a boil stirring frequently, sauce will begin to thicken and become a gravy. Mix 2 cups of the beef gravy with the shredded beef and the creamed corn. Cover with the mashed potatoes, sprinkle top with paprika and melted butter. Bake for 45 minutes or until an internal temperature of 165 is achieved. GERMAN STYLE POT ROAST INGREDIENTS 8 ounces Kayem Slow Cooked Choice Beef Pot Roast, drain au jus set aside 2 ounces cooked baby carrots 1 ounce celery 1/2" sliced 1 ounce sweet onion 1/2 " sliced, sautéed 1/2 cup red wine 1/3 cup ginger snap cookie, crush 1 cup egg noodles, cooked 1 tablespoon parsley, chopped 1 tablespoon unsalted butter, melted DIRECTIONS Separate the meat from the broth in the bag. -

Hors Descriptions Updated

Antipasto Display Bouquetière of Fresh Crudités and Dip a bountiful display of Italian Cheeses, Genoa Salami, a dramatic and colorful display of fresh vegetables such as green and black olives, pepperoncini, and yellow squash, zucchini, mushrooms, cauliflower, broccoli, balsamic marinated artichokes red and green bell pepper, and grape tomatoes, accompa- nied by red pepper and buttermilk ranch dips Arancini de Riso Creamy risotto rolled with Asiago Cheese, breaded and deep Boursin Cheese Soufflé fried, served with marinara sauce for dipping miniature boursin cheese soufflés in a panko crust garnished with red grape relish Artichoke Parmesan A rich spread of artichoke hearts and parmesan cheese Boursin Fig Flowers served on garlic toasted baguettes rich boursin cheese with a fig glaze baked in a phyllo shell Asiago Cheese Puffs: Boursin Shrimp Canapé Pate a choux dough blended with imported Asiago cheese phyllo cups filled with boursin shrimp cream and garnished and golden fried. Somehow the center stays soft and cheesy with red green and yellow pepper confetti and the out side is very crispy Brie Beggar’s Purse Asian Egg Rolls layers of crispy phyllo buttered pastry filled with Traditional wontons wrapped with Asian vegetables and fresh raspberries, toasted almonds and pork, deep fried until golden brown imported soft Brie Cheese – served warm Assorted Bruschetta Bruschetta Presentation Roasted Garlic and Sun Dried Tomato Grilled Chicken, Olive Tapenade, Red Pepper Pesto, and Feta Artichoke Asiago Cheese, and Plum Tomato Smoked Ham, Pineapple