The Idea of the Labyrinth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Turf Labyrinths Jeff Saward

English Turf Labyrinths Jeff Saward Turf labyrinths, or ‘turf mazes’ as they are popularly known in Britain, were once found throughout the British Isles (including a few examples in Wales, Scotland and Ireland), the old Germanic Empire (including modern Poland and the Czech Republic), Denmark (if the frequently encountered Trojaborg place-names are a reliable indicator) and southern Sweden. They are formed by cutting away the ground surface to leave turf ridges and shallow trenches, the convoluted pattern of which produces a single pathway, which leads to the centre of the design. Most were between 30 and 60 feet (9-18 metres) in diameter and usually circular, although square and other polygonal examples are known. The designs employed are a curious mixture of ancient classical types, found throughout the region, and the medieval types, found principally in England. Folklore and the scant contemporary records that survive suggest that they were once a popular feature of village fairs and other festivities. Many are found on village greens or commons, often near churches, but sometimes they are sited on hilltops and at other remote locations. By nature of their living medium, they soon become overgrown and lost if regular repair and re-cutting is not carried out, and in many towns and villages this was performed at regular intervals, often in connection with fairs or religious festivals. 50 or so examples are documented, and several hundred sites have been postulated from place-name evidence, but only eleven historic examples survive – eight in England and three in Germany – although recent replicas of former examples, at nearby locations, have been created at Kaufbeuren in Germany (2002) and Comberton in England (2007) for example. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

£75,000 Awarded to Browne's Folly Site

Foll- The e-Bulletin of The Folly Fellowship The Folly Fellowship is a Registered Charity No. 1002646 and a Company Limited by Guarantee No. 2600672 Issue 34: £75,000 awarded to January 2011 Browne’s Folly site Upcoming events: 06 March—Annual General Meeting starting at 2.30pm at athford Hill (Wiltshire) is a leased the manor at Monkton Far- East Haddon Village Hall, B haven for some of our rar- leigh in 1842 and used the folly as Northamptonshire. Details est flora and fauna, including the a project for providing employment were enclosed with the Journal White Heleborine and Twayblade during the agricultural depression. and are available from the F/F website www.follies.org.uk Orchid, and for Greater Horseshoe He also improved the condition of and Bechstein‟s Bats. Part of it is the parish roads and built a school 18-19 March—Welsh Week- owned by the Avon Wildlife Trust in the centre of the village where end with visits to Paxton‟s who received this month a grant of he personally taught the girls. Tower, the Cilwendeg Shell House, and the gardens and £75,000 to spend on infrastructure After his death on 2 August grotto at Dolfor. Details from and community projects such as 1851, the manor was leased to a [email protected] the provision of waymark trails and succession of tenants and eventu- information boards telling visitors ally sold to Sir Charles Hobhouse about the site and about its folly. in 1873: his descendants still own The money was awarded from the estate. -

Trsteno Arboretum, Croatia (This Is an Edited Version of a Previously Published Article by Jadranka Beresford-Peirse)

ancient Pterocarya stenoptera (champion), Thuyopsis dolobrata and Phyllocladus alpinus ‘Silver Blades’. We just had time to admire Michelia doltsopa in flower before having to leave this interesting garden. Our final visit was to Fonmom Castle, the home of Sir Brooke Boothby who had very kindly invited us all to lunch. We sat at a long table in a room orig- inally built in 1180, and remodelled in Georgian times with beautiful plaster- work and furnishings. After lunch we had a tour of the garden which is on shallow limestone soil, and at times windswept. We admired a large Fagus syl- vatica f. purpurea planted on the edge of the escarpment in 1818, that had been given buttress walls to hold the soil and roots. There was a small Sorbus domes- tica growing in the lawn and we learnt that this tree is a native in the country nearby. We walked through the closely planted ornamental walled garden into the large productive walled vegetable garden. This final visit was a splen- did ending to our tour, and having thanked our host for his warm hospitality, we said goodbye to fellow members and departed after a memorable four days, so rich in plant content and well organised by our leader Rose Clay. ARBORETUM NEWS Trsteno Arboretum, Croatia (This is an edited version of a previously published article by Jadranka Beresford-Peirse) Vicinis laudor sed aquis et sospite celo Plus placeo et cultu splendidioris heri Haec tibi sunt hominum vestigia certa viator Ars ubi naturam perficit apta rudem. (Trsteno, 1502) The inscription above, with its reference to “the visual traces of the human race” is carved onto a stone in a pergola at the Trsteno Arboretum, Croatia, a place of beauty arising like a phoenix from the ashes of wanton destruction and natural disasters. -

Curses by Graham Nelson

Curses by Graham Nelson Meldrew Estate Attic, 1993 Out on the Spire adamantine hand Potting Aunt Old Storage Room (1) (6) Room Jemima's Winery Battlements Bell Tower yellow rubber Lair demijohn, nasty-looking red steel wrench, gloves battery, tourist map wishbone D U End Game: Servant's Priest's Airing Room (7) (10) West Side Parish East Side Missed the Attic Hole (3) Roof Cupboard classical Chapel Church Chapel Point iron gothic-looking key, ancient prayer book, old sooty stick dictionary, scarf D D U D U Old Inside End Game: Stone Missed the Furniture Chimney Cupboard cupboard, medicine bottle, painting, skylight, Cross Point gift-wrapped parcel, bird whistle gas mask Dark East Hollow (2) Room Over the Annexe U Public D sepia photograph, East Wing Footpath cupboard nuts cord, flash Library Disused Dead End Storage Observatory Beside the romantic novel, book of Drive Twenties poetry glass ball canvas rucksack Souvenirs Alison's Writing Room (12) Room (11) projector window, mirror Tiny Balcony Curses by Graham Nelson Mildrew Hall Cellars, 1993 Infinity Symbol Cellars (1) Cellar (5) Wine West (3) Cellars (4) robot mouse, vent Hellish Place Hole in Cellars Wall South Curses by Graham Nelson Meldrew Estate Hole in Wall of Cellars South (Mouse Maze), 1993 small brass key Cellars South Curses by Graham Nelson Meldrew Estate Grounds, 1993 Up the Plane To Maze Tree D U Mosaic (2) (17) (23) (29) Garage (35) (38) (39) (40) (41) Behind Heavenly Family Tree Lawn (42) (43) (48) (54) Clearing Summer Place (8) Ornaments big motorised garden roller, -

University Park Gardens Guide and Tree Walk

University Park Gardens Guide and Tree Walk 1 We are proud of the those from Nottingham Welcome University’s landscaped and East Midlands in campuses and visitors Bloom, the local and 4 Horticultural highlights are welcome to enjoy our National Civic Trust and 9 Millennium Garden gardens, walks and trees. the British Association of 12 Lakeside Walk Landscape Industries. University Park has 14 Tree Walk The Friends of University been awarded a Green Please use this guide 16 University Park map Flag every year since to explore and enjoy Park encourage everyone to 22 Our other campuses enjoy the campus grounds and 2003. We were the first University Park. all are welcome at their events. 24 Green issues University to achieve this. w: nott.ac.uk/friends 31 Tree Walk map Other awards include 2 3 Horticultural highlights University Park is very much in the English landscape style, with rolling grassland, many trees, shrubs and water features. An adjoining lake divides it from Highfields Park, which is managed by Nottingham City Council. Formal displays In the summer the display beds are vibrant with exotic annuals One of our boldest displays and bedding plants. In spring is at the North Entrance they are awash with colour from beside the A52 roundabout. A biennials and spring bulbs. contemporary arrangement of informal beds for annual bedding A second, smaller area of formal is backed by a border of exotic bedding is at the West Entrance shrubs, bamboos and grasses, by the old lodges. In the summer, which add value in winter. These large pots of brilliant bedding are complemented by boulders plants enhance our involvement and areas of cobbles. -

Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal Timothy Hanford Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/427 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by TIMOTHY HANFORD A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Classics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ©2014 TIMOTHY HANFORD All Rights Reserved ii This dissertation has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in Classics in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ronnie Ancona ________________ _______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Dee L. Clayman ________________ _______________________________ Date Executive Officer James Ker Joel Lidov Craig Williams Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by Timothy Hanford Advisor: Professor Ronnie Ancona This dissertation explores the relationship between Senecan tragedy and Virgil’s Aeneid, both on close linguistic as well as larger thematic levels. Senecan tragic characters and choruses often echo the language of Virgil’s epic in provocative ways; these constitute a contrastive reworking of the original Virgilian contents and context, one that has not to date been fully considered by scholars. -

Landscape and Architecture COMMONWEALTH of AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969

702132/702835 European Architecture B landscape and architecture COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 Warning This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of the University of Melbourne pursuant to Part VB of the Copyright Act 1968 (the Act). The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. do not remove this notice garden scene from a C15th manuscript of the Roman de la Rose Christopher Thacker, The History of Gardens (Berkeley [California] 1979), p 87 Monreale Cathedral, Palermo, Sicily, 1176-82: cloisters of the Benedictine Monastery commercial slide RENAISSANCERENAISSANCE && MANNERISMMANNERISM gardens of the Villa Borghese, Rome: C17th painting J D Hunt & Peter Willis, The Genius of the Place: the English Landscape Garden 1620-1820 (London 1975), p 61 Villa Medici di Castello, Florence, with gardens as improved by Bernardo Buontalenti [?1590s], from the Museo Topografico, Florence Monique Mosser & Georges Teyssot [eds], The History of Garden Design: The Western Tradition from the Renaissance to the Present Day (London 1991 [1990]), p 39 Chateau of Bury, built by Florimund Robertet, 1511-1524, with gardens possibly by Fra Giocondo W H Adams, The French Garden 1500-1800 (New York 1979), p 19 Chateau of Gaillon (Amboise), begun 1502, with gardens designed by Pacello de Mercogliano Adams, The French Garden, p 17 Casino di Pio IV, Vatican gardens, -

ROMAN ARCHITEXTURE: the IDEA of the MONUMENT in the ROMAN IMAGINATION of the AUGUSTAN AGE by Nicholas James Geller a Dissertatio

ROMAN ARCHITEXTURE: THE IDEA OF THE MONUMENT IN THE ROMAN IMAGINATION OF THE AUGUSTAN AGE by Nicholas James Geller A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Basil J. Dufallo, Chair Associate Professor Ruth Rothaus Caston Professor Bruce W. Frier Associate Professor Achim Timmermann ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of many people both within and outside of academia. I would first of all like to thank all those on my committee for reading drafts of my work and providing constructive feedback, especially Basil Dufallo and Ruth R. Caston, both of who read my chapters at early stages and pushed me to find what I wanted to say – and say it well. I also cannot thank enough all the graduate students in the Department of Classical Studies at the University of Michigan for their support and friendship over the years, without either of which I would have never made it this far. Marin Turk in Slavic Languages and Literature deserves my gratitude, as well, for reading over drafts of my chapters and providing insightful commentary from a non-classicist perspective. And I of course must thank the Department of Classical Studies and Rackham Graduate School for all the financial support that I have received over the years which gave me time and the peace of mind to develop my ideas and write the dissertation that follows. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………………ii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS……………………………………………………………………iv ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………………....v CHAPTER I. -

Lord Sumption and the Values of Life, Liberty and Security: Before and Since the COVID-19 Outbreak John Coggon

Extended essay J Med Ethics: first published as 10.1136/medethics-2021-107332 on 12 July 2021. Downloaded from Lord Sumption and the values of life, liberty and security: before and since the COVID-19 outbreak John Coggon Correspondence to ABSTRACT In public spheres beyond government, values Professor John Coggon, Centre Lord Sumption, a former Justice of the Supreme Court, have been raised and debated. Perhaps inevitably, for Health, Law, and Society, University of Bristol Law School, has been a prominent critic of coronavirus restrictions given the nature and prominence of different plat- Bristol, BS8 1HH, UK; regulations in the UK. Since the start of the pandemic, he forms for public discourse, particular voices and john. coggon@ bristol. ac. uk has consistently questioned both the policy aims and the views have found particularly privileged place in regulatory methods of the Westminster government. He critical discussions of pandemic responses in the Received 15 February 2021 UK. Among these are the arguments of Lord Sump- Accepted 19 May 2021 has also challenged rationales that hold that all lives are of equal value. In this paper, I explore and question Lord tion, a former Justice of the Supreme Court. Lord Sumption’s views on morality, politics and law, querying Sumption is an eloquent and vocal critic of the the coherence of his broad philosophy and his arguments restrictions regulations (and related points of offi- regarding coronavirus regulations with his judicial cial guidance) that have been implemented since decision in the assisted- dying case of R (Nicklinson) v March 2020. These regulations have significantly Ministry of Justice. -

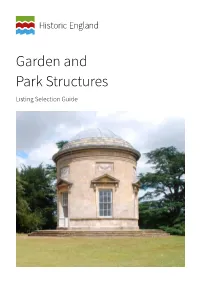

Garden and Park Structures Listing Selection Guide Summary

Garden and Park Structures Listing Selection Guide Summary Historic England’s twenty listing selection guides help to define which historic buildings are likely to meet the relevant tests for national designation and be included on the National Heritage List for England. Listing has been in place since 1947 and operates under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. If a building is felt to meet the necessary standards, it is added to the List. This decision is taken by the Government’s Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). These selection guides were originally produced by English Heritage in 2011: slightly revised versions are now being published by its successor body, Historic England. The DCMS‘ Principles of Selection for Listing Buildings set out the over-arching criteria of special architectural or historic interest required for listing and the guides provide more detail of relevant considerations for determining such interest for particular building types. See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/principles-of- selection-for-listing-buildings. Each guide falls into two halves. The first defines the types of structures included in it, before going on to give a brisk overview of their characteristics and how these developed through time, with notice of the main architects and representative examples of buildings. The second half of the guide sets out the particular tests in terms of its architectural or historic interest a building has to meet if it is to be listed. A select bibliography gives suggestions for further reading. This guide looks at buildings and other structures found in gardens, parks and indeed designed landscapes of all types from the Middle Ages to the twentieth century. -

The RHS Lindley Library IBRARY L INDLEY RHS, L

Occasional Papers from The RHS Lindley Library IBRARY L INDLEY RHS, L VOLUME NINE DECEMBER 2012 The history of garden history Cover illustration: Engraved illustration of the gardens at Versailles, from Les Jardins: histoire et description by Arthur Mangin (c.1825–1887), published in 1867. Occasional Papers from the RHS Lindley Library Editor: Dr Brent Elliott Production & layout: Richard Sanford Printed copies are distributed to libraries and institutions with an interest in horticulture. Volumes are also available on the RHS website (www. rhs.org.uk/occasionalpapers). Requests for further information may be sent to the Editor at the address (Vincent Square) below, or by email (brentelliottrhs.org.uk). Access and consultation arrangements for works listed in this volume The RHS Lindley Library is the world’s leading horticultural library. The majority of the Library’s holdings are open access. However, our rarer items, including many mentioned throughout this volume, are fragile and cannot take frequent handling. The works listed here should be requested in writing, in advance, to check their availability for consultation. Items may be unavailable for various reasons, so readers should make prior appointments to consult materials from the art, rare books, archive, research and ephemera collections. It is the Library’s policy to provide or create surrogates for consultation wherever possible. We are actively seeking fundraising in support of our ongoing surrogacy, preservation and conservation programmes. For further information, or to request an appointment, please contact: RHS Lindley Library, London RHS Lindley Library, Wisley 80 Vincent Square RHS Garden Wisley London SW1P 2PE Woking GU23 6QB T: 020 7821 3050 T: 01483 212428 E: library.londonrhs.org.uk E : library.wisleyrhs.org.uk Occasional Papers from The RHS Lindley Library Volume 9, December 2012 B.