From Epic to Romance: the Paralysis of the Hero in the Prise D'orange

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

£75,000 Awarded to Browne's Folly Site

Foll- The e-Bulletin of The Folly Fellowship The Folly Fellowship is a Registered Charity No. 1002646 and a Company Limited by Guarantee No. 2600672 Issue 34: £75,000 awarded to January 2011 Browne’s Folly site Upcoming events: 06 March—Annual General Meeting starting at 2.30pm at athford Hill (Wiltshire) is a leased the manor at Monkton Far- East Haddon Village Hall, B haven for some of our rar- leigh in 1842 and used the folly as Northamptonshire. Details est flora and fauna, including the a project for providing employment were enclosed with the Journal White Heleborine and Twayblade during the agricultural depression. and are available from the F/F website www.follies.org.uk Orchid, and for Greater Horseshoe He also improved the condition of and Bechstein‟s Bats. Part of it is the parish roads and built a school 18-19 March—Welsh Week- owned by the Avon Wildlife Trust in the centre of the village where end with visits to Paxton‟s who received this month a grant of he personally taught the girls. Tower, the Cilwendeg Shell House, and the gardens and £75,000 to spend on infrastructure After his death on 2 August grotto at Dolfor. Details from and community projects such as 1851, the manor was leased to a [email protected] the provision of waymark trails and succession of tenants and eventu- information boards telling visitors ally sold to Sir Charles Hobhouse about the site and about its folly. in 1873: his descendants still own The money was awarded from the estate. -

Trsteno Arboretum, Croatia (This Is an Edited Version of a Previously Published Article by Jadranka Beresford-Peirse)

ancient Pterocarya stenoptera (champion), Thuyopsis dolobrata and Phyllocladus alpinus ‘Silver Blades’. We just had time to admire Michelia doltsopa in flower before having to leave this interesting garden. Our final visit was to Fonmom Castle, the home of Sir Brooke Boothby who had very kindly invited us all to lunch. We sat at a long table in a room orig- inally built in 1180, and remodelled in Georgian times with beautiful plaster- work and furnishings. After lunch we had a tour of the garden which is on shallow limestone soil, and at times windswept. We admired a large Fagus syl- vatica f. purpurea planted on the edge of the escarpment in 1818, that had been given buttress walls to hold the soil and roots. There was a small Sorbus domes- tica growing in the lawn and we learnt that this tree is a native in the country nearby. We walked through the closely planted ornamental walled garden into the large productive walled vegetable garden. This final visit was a splen- did ending to our tour, and having thanked our host for his warm hospitality, we said goodbye to fellow members and departed after a memorable four days, so rich in plant content and well organised by our leader Rose Clay. ARBORETUM NEWS Trsteno Arboretum, Croatia (This is an edited version of a previously published article by Jadranka Beresford-Peirse) Vicinis laudor sed aquis et sospite celo Plus placeo et cultu splendidioris heri Haec tibi sunt hominum vestigia certa viator Ars ubi naturam perficit apta rudem. (Trsteno, 1502) The inscription above, with its reference to “the visual traces of the human race” is carved onto a stone in a pergola at the Trsteno Arboretum, Croatia, a place of beauty arising like a phoenix from the ashes of wanton destruction and natural disasters. -

Curses by Graham Nelson

Curses by Graham Nelson Meldrew Estate Attic, 1993 Out on the Spire adamantine hand Potting Aunt Old Storage Room (1) (6) Room Jemima's Winery Battlements Bell Tower yellow rubber Lair demijohn, nasty-looking red steel wrench, gloves battery, tourist map wishbone D U End Game: Servant's Priest's Airing Room (7) (10) West Side Parish East Side Missed the Attic Hole (3) Roof Cupboard classical Chapel Church Chapel Point iron gothic-looking key, ancient prayer book, old sooty stick dictionary, scarf D D U D U Old Inside End Game: Stone Missed the Furniture Chimney Cupboard cupboard, medicine bottle, painting, skylight, Cross Point gift-wrapped parcel, bird whistle gas mask Dark East Hollow (2) Room Over the Annexe U Public D sepia photograph, East Wing Footpath cupboard nuts cord, flash Library Disused Dead End Storage Observatory Beside the romantic novel, book of Drive Twenties poetry glass ball canvas rucksack Souvenirs Alison's Writing Room (12) Room (11) projector window, mirror Tiny Balcony Curses by Graham Nelson Mildrew Hall Cellars, 1993 Infinity Symbol Cellars (1) Cellar (5) Wine West (3) Cellars (4) robot mouse, vent Hellish Place Hole in Cellars Wall South Curses by Graham Nelson Meldrew Estate Hole in Wall of Cellars South (Mouse Maze), 1993 small brass key Cellars South Curses by Graham Nelson Meldrew Estate Grounds, 1993 Up the Plane To Maze Tree D U Mosaic (2) (17) (23) (29) Garage (35) (38) (39) (40) (41) Behind Heavenly Family Tree Lawn (42) (43) (48) (54) Clearing Summer Place (8) Ornaments big motorised garden roller, -

Our Partners

• Leopold Museum • Liliputbahn miniature railway, Our partners Donauparkbahn miniature railway, • Albertina Prater train • Apple Strudel Show • Madame Tussauds • Bank Austria Kunstforum • MAK- Austrian Museum of Applied • Austrian National Library with Arts / Contemporary Art & MAK State Hall, Papyrus Museum, Branch Geymüllerschlössel Globe and Esperanto Museum, • Mozarthaus Vienna Literature Museum • mumok- Museum of Modern Art • Bank Austria Kunstforum Ludwig Foundation • Beethoven Pasqualati House • Museum at the Abbey of the Scots • Beethoven Museum Heiligenstadt • Museum of Military History • Belvedere (Upper and Lower • Museum of Natural History Belvedere, Belvedere 21) • Otto Wagner’s Court Pavilion • City Cruise (Hietzing) • Collection of Anatomical Pathology • Otto Wagner Pavilion Karlsplatz in the Madhouse Tower • Porcelain Museum at Augarten • Danube Tower • Prater Museum • Desert Experience House • Remise – Wiener Linien’s Schönbrunn Transport Museum • Dom Museum Wien • Roman City Carnuntum • Esterházy Palace • Schloss Hof Estate • Forchtenstein Castle • Schloss Niederweiden • Liechtenstein Castle • Schlumberger Cellars • Guided Tour of the UN • Schönbrunn Panorama Train Headquarters • Schönbrunn Palace (Grand Tour) • Haydn House incl. Gloriette, Maze, Privy Garden, • Hofburg- Imperial Apartments, Sisi Children’s Museum at Schönbrunn Museum, Imperial Silver Collection Palace, Orangery Garden • Hofmobiliendepot - Imperial • Schönbrunn Zoo Furniture Collection • Sigmund Freud Museum • House of Music • Schubert’s Birthplace • -

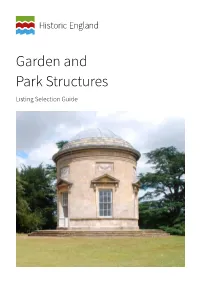

Garden and Park Structures Listing Selection Guide Summary

Garden and Park Structures Listing Selection Guide Summary Historic England’s twenty listing selection guides help to define which historic buildings are likely to meet the relevant tests for national designation and be included on the National Heritage List for England. Listing has been in place since 1947 and operates under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. If a building is felt to meet the necessary standards, it is added to the List. This decision is taken by the Government’s Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). These selection guides were originally produced by English Heritage in 2011: slightly revised versions are now being published by its successor body, Historic England. The DCMS‘ Principles of Selection for Listing Buildings set out the over-arching criteria of special architectural or historic interest required for listing and the guides provide more detail of relevant considerations for determining such interest for particular building types. See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/principles-of- selection-for-listing-buildings. Each guide falls into two halves. The first defines the types of structures included in it, before going on to give a brisk overview of their characteristics and how these developed through time, with notice of the main architects and representative examples of buildings. The second half of the guide sets out the particular tests in terms of its architectural or historic interest a building has to meet if it is to be listed. A select bibliography gives suggestions for further reading. This guide looks at buildings and other structures found in gardens, parks and indeed designed landscapes of all types from the Middle Ages to the twentieth century. -

The European Garden I :

The European Garden I : ............................................ I ............................................ Progetto editoriale: Angelo Pontecorboli Tutti i diritti riservati Angelo Pontecorboli Editore, Firenze www.pontecorboli.com – [email protected] ISBN 978-88-00000-00-0 2 Mariella Zoppi e European Garden ANGELO PONTECORBOLI EDITORE FIRENZE 3 4 C 5 Introduction As with all written histories of the garden, this one begins with the most ancient civilizations and thus dedicates much attention to the Roman Empire. is way, the ordinary has little that is ritual or can be foreseen and one can witness the true origins of gardens which arrived from western culture. ese origins were not lost in the centuries which passed by each other, but were a constant source of inspiration for the civilizations which came and went in the Mediterranean Basin. e Mediterranean, for an extremely long period stretching from 2000 BC to the late fourteenth century, was almost exclusively the scenery of western culture. Diverse peoples acquired economic and political hegemony, they imposed laws, customs and artistic models which merged with pre-existing backgrounds and styles which then expanded throughout Northern European and African countries. Ideas from the East, such as science, religion and artistic models, fil- tered throughout the Mediterranean. Nomadic populations reached Mediterranean shores and so cultures and customs were brought to- gether for several centuries in a relatively small circle. It was on the edges of the Mediterranean where the two fundamental ideas of gar- den design, the formal and the informal, were created and confronted each other. Here, the garden became the idealization of a perfect and immutable world, the mimesis of nature. -

Visitor Attractions

Visitor Attractions As a former imperial city, Vienna has a vast cultural imperial apartments and over two dozen collections heritage spanning medieval times to the present day. – the legacy of the collecting passion of the Habsburg Top attractions include the Gothic St. Stephen’s Cathe- dynasty. Viennese art nouveau (Jugendstil) has also dral, baroque imperial palaces and mansions and brought forth unique places of interest such as the Se- the magnificent Ring Boulevard with the State Opera, cession with its gilded leaf cupola. Contemporary archi- Burgtheater (National Theater), Votive Church, City Hall, tecture is to be found in the shape of the Haas-Haus, Parliament and the Museums of Fine Arts and Natural whose glass front reflects St. Stephen’s Cathedral, and History. The former imperial residences Hofburg and the Gasometers, former gas storage facilities which Schönbrunn also offer the opportunity to follow in have been converted into a residential and commercial imperial footsteps. Schönbrunn zoo and park shine complex. This mix of old and new, tradition and moder- in baroque splendor, while Hofburg Palace boasts nity, is what gives Vienna its extra special flair. © WienTourismus/Karl Thomas Thomas WienTourismus/Karl © Osmark WienTourismus/Robert © Osmark WienTourismus/Robert © Anker Clock TIP This gilded masterpiece of art nouveau was created in 1911 by the Danube Tower painter and sculptor Franz von Matsch. Every day at noon, twelve An unforgettable panorama of Vienna’s Danube scenery, the old historical Viennese figures parade across the clock to musical ac- city and the Vienna Woods is afforded at 170m in the Danube Tow- companiment. Christmas carols can be heard at 17:00 and 18:00 er. -

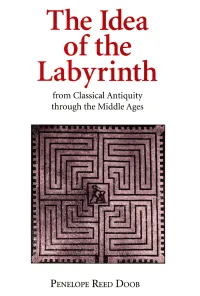

The Idea of the Labyrinth

·THE IDEA OF · THE LABYRINTH · THE IDEA OF · THE LABYRINTH from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages Penelope Reed Doob CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS ITHACA AND LONDON Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Copyright © 1990 by Cornell University First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 1992 Second paperback printing 2019 All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-8014-2393-2 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-3845-6 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-3846-3 (pdf) ISBN 978-1-5017-3847-0 (epub/mobi) Librarians: A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress An open access (OA) ebook edition of this title is available under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by- nc-nd/4.0/. For more information about Cornell University Press’s OA program or to download our OA titles, visit cornellopen.org. Jacket illustration: Photograph courtesy of the Soprintendenza Archeologica, Milan. For GrahamEric Parker worthy companion in multiplicitous mazes and in memory of JudsonBoyce Allen and Constantin Patsalas Contents List of Plates lX Acknowledgments: Four Labyrinths xi Abbreviations XVll Introduction: Charting the Maze 1 The Cretan Labyrinth Myth 11 PART ONE THE LABYRINTH IN THE CLASSICAL AND EARLY CHRISTIAN PERIODS 1. -

GULLEY GREENHOUSE 2021 YOUNG PLANT ALSTROEMERIA ‘Initicancha Moon’ Hilverdaflorist

GULLEY GREENHOUSE 2021 YOUNG PLANT ALSTROEMERIA ‘Initicancha Moon’ HilverdaFlorist ANTIRRHINUM ‘Drew’s Folly’ Plant Select LAVENDER ‘New Madrid® Purple Star’ GreenFuse Botanicals AQUILEGIA ‘Early Bird Purple Blue’ LUPINUS ‘Staircase Red/White’ GERANIUM pratense ‘Dark Leaf Purple’ PanAm Seed GreenFuse Botanicals ECHINACEA ‘SunSeekers Rainbow’ Innoflora 2021 NEW VARIETIES 2021 NEW VARIETIES GULLEY GREENHOUSE 2020-21 Young Plant Assortment LUPINUS ‘Westcountry Towering Inferno’ Must Have Perennials 2021 CONTENTS HELLO! GENERAL INFORMATION Welcome to the 2020-2021 Gulley Greenhouse Prices, Discounts, Shipping, Young Plant Catalog Minimums, Claims..................2 At Gulley Greenhouse we specialize in custom growing plugs Tray Sizes....................................3 and liners of perennials, herbs, ornamental grasses, and Broker Listing...............................4 specialty annuals. Our passion is to provide finished growers with a wide selection of high quality young plants to choose from. Having been established FEATURED AFFILIATIONS as a family business for over 40 years, we’re proud to consider Featured Programs......................5 (Featured breeders and suppliers whose ourselves connected to the industry. We do our best to stay at the premium plants are included in our program) forefront of the new technology and variety advancements that are being made every year (and every day!) FAIRY FLOWERS® THANK YOU Fairy Flower® Introduction.......... 8 Thanks to all of our customers for your continued support! We Fairy Flower® Varieties............... 8 sincerely appreciate your orders and the confidence you’ve shown (By Common name, including sizes, in our products and company. As always, we strive to produce descriptions & lead times) quality plants perfectly suited for easy production and successful sales to the end consumer. SPECIALTY ANNUALS Annual Introduction......................12 We’re looking forward to another great season, with lots of new varieties to offer and the same quality you’ve come to expect. -

Frogs of the Feywild

Table of Contents Adventure Outline...................................................................................................... 1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 1 Background............................................................................................................ 1 Overview................................................................................................................ 1 Adventure Hooks...................................................................................................2 Chapter 1 — The Chaotic Maze..................................................................................3 G1. Garden Gate................................................................................................3 G2. Hedge Maze................................................................................................4 G3. Garden Party...............................................................................................5 Development......................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 2 — Time of the Seasons..............................................................................6 G4. Pond............................................................................................................ 6 G5. Summer Terrace..........................................................................................6 G6. Winter Terrace............................................................................................7 -

Arbor, Trellis, Or Pergola—What's in Your Garden?

ENH1171 Arbor, Trellis, or Pergola—What’s in Your Garden? A Mini-Dictionary of Garden Structures and Plant Forms1 Gail Hansen2 ANY OF THE garden features and planting Victorian era (mid-nineteenth century) included herbaceous forms in use today come from the long and rich borders, carpet bedding, greenswards, and strombrellas. M horticultural histories of countries around the world. The use of garden structures and intentional plant Although many early garden structures and plant forms forms originated in the gardens of ancient Mesopotamia, have changed little over time and are still popular today, Egypt, Persia, and China (ca. 2000–500 BC). The earliest they are not always easy to identify. Structures have been gardens were a utilitarian mix of flowering and fruiting misidentified and names have varied over time and by trees and shrubs with some herbaceous medicinal plants. region. Read below to find out more about what might be in Arbors and pergolas were used for vining plants, and your garden. Persian gardens often included reflecting pools and water features. Ancient Romans (ca. 100) were perhaps the first to Garden Structures for People plant primarily for ornamentation, with courtyard gardens that included trompe l’oeil, topiary, and small reflecting Arbor: A recessed or somewhat enclosed area shaded by pools. trees or shrubs that serves as a resting place in a wooded area. In a more formal garden, an arbor is a small structure The early medieval gardens of twelfth-century Europe with vines trained over latticework on a frame, providing returned to a more utilitarian role, with culinary and a shady place. -

Pdfperiurban Parks Fact Sheets

BARCELONA ESPAGNE Parc de Collserola Parc Serralada Litoral Surface : 8 070 hectares Population : 3 millions residents Cerdanyola Region : Catalunya Parc Natural del Garraf Organisme gestionnaire: Consorci del Parc de Collserola Adress : Carretera de l'Església, 92 E 08017 Barcelona Mataró Tel. +34 93 280 06 72 BARCELONA Fax. +34 93 280 60 74 Aeroport del Prat e-mail : [email protected] web : http://parccollserola.amb.es La Sierra de Collserola is part of the coastal cordillera, a mountainous, 300 km-long landscape along the Mediterranean Ocean. The park's northern boundary is the Besòs river and Vallès depression, and it is bordered by the Llobregat river and city of Barcelona in the south. In 1987, a special management and environmental protection plan was established for Collserola. It is based on the principle of protecting and strengthening ecosystems. At the same time, infrastructure construction has allowed the public to use this space rationally, without endangering the park's precious natural and landscape resources. The site, managed by the Collserola park Consortium, is a diversified spectrum of natural Mediterranean environments, where forest areas predominate. There are also a few agricultural areas. The park's highest point is on the Tibidabo mountain (512 m). It has a typically Mediterranean climate. The average temperature is 14°C, with pluviometry of 620 mm/year, although microclimates due to diverse hilly terrain must also be considered. Natural heritage. The park is home to a wealth of plant and animal species characteristic of Mediterranean ecosystems. Thus, endemic Iberian Peninsula species are found among the arthropods, some of which have been observed exclusively on the Collserola site.