Lord Sumption and the Values of Life, Liberty and Security: Before and Since the COVID-19 Outbreak John Coggon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Master Bibliography

SELECTED ITEMS OF MEDIA COVERAGE Selected Broadcast Comment Witness on BBC Radio 4 the Moral Maze, broadcast live at 2000 Wednesday 16th June 2010 Debate chaired by Quentin Cooper with Sir David King, Chris Whitty and Richard Davis, Material World, Radio 4 1630 Thursday 3rd January 2008 [on directions for science and innovation] Debate chaired by Sarah Montague with Tom Shakespeare, Today Programme, Radio 4 0850-0900, Friday Tuesday 4th September 2007 [on role of public in consultation on new technologies] D. Coyle, et al, Risky Business, Radio 4 ‘Analysis’ documentary, broadcast 11 December 2030, 14 December 2130, 2003 [interview on the precautionary principle] Tom Feilden, Political Interests in Biotechnology Science, Today Programme, Radio 4 0834-0843, Friday 19th September 2003 [on exercise of pressure in relation to GM Science Review Panel]. Roger Harrabin, Science Scares, Interview on the Today Programme, BBC Radio 4 0832, 10th January 2002 [on EEA report on risk and precaution]. ‘Sci-Files’, Australian National Radio, October 2000 [interview on risk, uncertainty and GM]. ‘Risk and Society’, The Commission, BBC Radio 4, 2000, 11 October 2000 [commission witness on on theme of risk and society] Selected Press Coverage of Work Andrew Jack, Battle Lines, Financial Times Magazine, 24th June 2011 [on need for tolerance of scepticism about science] Paul Dorfman, Who to Trust on Nuclear, Guardian, 14th April 2011 Charles Clover, Britain’s nuclear confidence goes into meltdown, Sunday Times, 20th March 2011 [on potential for a global sustainable -

The Production of Religious Broadcasting: the Case of The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenGrey Repository The Production of Religious Broadcasting: The Case of the BBC Caitriona Noonan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Centre for Cultural Policy Research Department of Theatre, Film and Television University of Glasgow Glasgow G12 8QQ December 2008 © Caitriona Noonan, 2008 Abstract This thesis examines the way in which media professionals negotiate the occupational challenges related to television and radio production. It has used the subject of religion and its treatment within the BBC as a microcosm to unpack some of the dilemmas of contemporary broadcasting. In recent years religious programmes have evolved in both form and content leading to what some observers claim is a “renaissance” in religious broadcasting. However, any claims of a renaissance have to be balanced against the complex institutional and commercial constraints that challenge its long-term viability. This research finds that despite the BBC’s public commitment to covering a religious brief, producers in this style of programming are subject to many of the same competitive forces as those in other areas of production. Furthermore those producers who work in-house within the BBC’s Department of Religion and Ethics believe that in practice they are being increasingly undermined through the internal culture of the Corporation and the strategic decisions it has adopted. This is not an intentional snub by the BBC but a product of the pressure the Corporation finds itself under in an increasingly competitive broadcasting ecology, hence the removal of the protection once afforded to both the department and the output. -

The Idea of the Labyrinth

·THE IDEA OF · THE LABYRINTH · THE IDEA OF · THE LABYRINTH from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages Penelope Reed Doob CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS ITHACA AND LONDON Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Copyright © 1990 by Cornell University First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 1992 Second paperback printing 2019 All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-8014-2393-2 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-3845-6 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-3846-3 (pdf) ISBN 978-1-5017-3847-0 (epub/mobi) Librarians: A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress An open access (OA) ebook edition of this title is available under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by- nc-nd/4.0/. For more information about Cornell University Press’s OA program or to download our OA titles, visit cornellopen.org. Jacket illustration: Photograph courtesy of the Soprintendenza Archeologica, Milan. For GrahamEric Parker worthy companion in multiplicitous mazes and in memory of JudsonBoyce Allen and Constantin Patsalas Contents List of Plates lX Acknowledgments: Four Labyrinths xi Abbreviations XVll Introduction: Charting the Maze 1 The Cretan Labyrinth Myth 11 PART ONE THE LABYRINTH IN THE CLASSICAL AND EARLY CHRISTIAN PERIODS 1. -

Saturday, July 7, 2018 | 15 | WATCH Monday, July 9

6$785'$<-8/< 7+,6,6123,&1,& _ )22' ,16,'( 7+,6 :((. 6+233,1* :,1(6 1$',<$ %5($.6 &KHFNRXW WKH EHVW LQ ERWWOH 683(50$5.(7 %(67 %8<6 *UDE WKH ODWHVW GHDOV 75,(' $1' 7(67(' $// 7+( 58/(6 :H FKHFN RXW WRS WUDYHO 1$',<$ +XVVDLQ LV D KDLUGU\HUV WR ORRN ZDQWDQGWKDW©VZK\,IHHOVR \RXGRQ©WHDWZKDW\RX©UHJLYHQ WRWDO UXOHEUHDNHU OXFN\§ WKHQ \RX JR WR EHG KXQJU\§ JRRG RQ WKH PRYH WKHVH GD\V ¦,©P D 6KH©V ZRQ 7KLV UHFLSH FROOHFWLRQ DOVR VHHV /XFNLO\ VKH DQG KXVEDQG $EGDO SDUW RI WZR YHU\ %DNH 2II SXW KHU IOLS D EDNHG FKHHVHFDNH KDYH PDQDJHG WR SURGXFH RXW D VOHZ RI XSVLGH GRZQ PDNH D VLQJOH FKLOGUHQ WKDW DUHQ©W IXVV\HDWHUV GLIIHUHQW ZRUOGV ¤ ,©P %ULWLVK HFODLU LQWR D FRORVVDO FDNH\UROO VR PXFK VR WKDW WKH ZHHN EHIRUH 5(/$; DQG ,©P %DQJODGHVKL§ WKH FRRNERRNV DQG LV DOZD\V LQYHQW D ILVK ILQJHU ODVDJQH ZH FKDW VKH KDG DOO WKUHH *$0(6 $336 \HDUROG H[SODLQV ¦DQG UHDOO\ VZDS WKH SUDZQ LQ EHJJLQJ KHU WR GROH RXW IUDJUDQW &RQMXUH XS RQ WKH WHOO\ ¤ SUDZQ WRDVW IRU FKLFNHQ DQG ERZOIXOV RI ILVK KHDG FXUU\ EHFDXVH ,©P SDUW RI WKHVH 1DGL\D +XVVDLQ PDJLFDO DWPRVSKHUH WZR DPD]LQJ ZRUOGV , KDYH ¦VSLNH§ D GLVK RI PDFDURQL ¦7KH\ ZHUH DOO RYHU LW OLNH WHOOV (//$ FKHHVH ZLWK SLFFDOLOOL ¤ WKH ¨0XPP\ 3OHDVH FDQ ZH KDYH 086,& QR UXOHV DQG QR UHVWULFWLRQV§ :$/.(5 WKDW 5(/($6(6 ZRPDQ©V D PDYHULFN WKDW ULJKW QRZ"© , ZDV OLNH ¨1R +HQFH ZK\ WKUHH \HDUV RQ IURP IRRG LV PHDQW +RZHYHU KHU DSSURDFK WR WKDW©V WRPRUURZ©V GLQQHU ,©YH :H OLVWHQ WR WKH ZLQQLQJ *UHDW %ULWLVK %DNH 2II WR EH IXQ FODVKLQJDQG PL[LQJ IODYRXUVDQG MXVW FRRNHG LW HDUO\ \RX©YH JRW ODWHVW DOEXPV WKH /XWRQERUQ -

University of Dundee BBC Moral Maze Lawrence, John; Visser, Jacky

University of Dundee BBC moral maze Lawrence, John; Visser, Jacky; Reed, Chris Published in: Computational Models of Argument - Proceedings of COMMA 2018 DOI: 10.3233/978-1-61499-906-5-465 Publication date: 2018 Licence: CC BY-NC Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication in Discovery Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Lawrence, J., Visser, J., & Reed, C. (2018). BBC moral maze: Test your argument. In S. Modgil, K. Budzynska, J. Lawrence, & K. Budzynska (Eds.), Computational Models of Argument - Proceedings of COMMA 2018 (Vol. 305, pp. 465-466). (Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications; Vol. 305). IOS Press. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-906-5-465 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in Discovery Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from Discovery Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 Computational Models of Argument 465 S. Modgil et al. (Eds.) © 2018 The authors and IOS Press. -

BBC Religion & Ethics Review

BBC Religion & Ethics Review December 2017 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. FOREWORD ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 2. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................................. 5 3. THE ROLE OF THE BBC ............................................................................................................................................... 8 4. THE CHALLENGES WE FACE ............................................................................................................................... 11 5. HOW WE WILL RESPOND .................................................................................................................................... 14 6. CHANGING HOW WE DO THINGS ............................................................................................................. 26 7. APPENDICES ...................................................................................................................................................................... 30 2 1. FOREWORD The start of a new Charter period is a good time for the BBC to assess how we are delivering on the religious and ethical aspects of our public service mission. We know – our research tells us – that today’s audiences are interested in learning more in this area. People of all ages, and of all faiths and none, -

Lawyers in the Moral Maze

Volume 49 Issue 4 Article 4 2004 Lawyers in the Moral Maze Mark A. Sargent Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr Part of the Accounting Law Commons, Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, and the Securities Law Commons Recommended Citation Mark A. Sargent, Lawyers in the Moral Maze, 49 Vill. L. Rev. 867 (2004). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr/vol49/iss4/4 This Symposia is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Law Review by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Sargent: Lawyers in the Moral Maze 2004] LAWYERS IN THE MORAL MAZE MARK A. SARGENT* I. INTRODUCTION T HE Securities and Exchange Commission's Standards of Professional Conduct for Attorneys1 represent an attempt to solve a problem. The problem is that ethical obligations, state law and self-interest apparently do not give lawyers sufficient incentives to report law violations by corporate managers "up the ladder" to appropriate decisionmakers within the corpo- rate client, or to disclose illegality to regulators. That problem is consid- ered serious, because it is believed to have resulted in lawyers' at least passive complicity in managerial wrongdoing. That complicity violated lawyers' fiduciary obligation to their corporate client and betrayed their public trust as gatekeepers, thereby contributing to the recent epidemic of corporate fraud and corporate governance failures. Let's assume, for the sake of argument, that the problem, as just defined, is real and serious. -

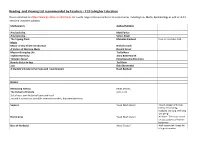

Reading and Viewing List Recommended by Teachers : Y13 to Higher Education

Reading and Viewing List recommended by Teachers : Y13 to Higher Education Please also check out https://www.gresham.ac.uk/schools for a wide range of lectures online in all subject areas, including Law, Media, Epidemiology as well as all the ‘standard’ academic subjects. Mathematics Author/Publisher Any books by… Matt Parker Any books by… Simon Singh The Tipping Point Malcolm Gladwell How an idea takes hold… Music Music- A Very Short Introduction Nicholas Cook A History of Western Music Donald Grout Music in Everyday Life Tia DeNora Stylistic Harmony Anna Butterworth ‘Western Music’ Encyclopaedia Britannica How to Listen to Jazz Ted Gioia Jazz Bob Blumenthal A Student’s Guide to Harmony and Counterpoint Hugh Benham History Rethinking History Keith Jenkins The Pursuit of History John Tosh Select your own historical topic and read around it as much as possible- internet searches, documentaries etc. Sapiens Yuval Noah Harari ‘Grand-Sweep’ of human history. Fascinating, readable and long. Will keep you going! Homo Deus Yuval Noah Harari As above. The future based on past patterns of human behaviour. Bess of Hardwick Mary S Lovell Well researched. Great life of a great woman. A History of the World in 100 Objects Neil MacGregor 100 objects from the British Museum, and what they show us about human civilisation. Art: AQA Art and Design Student Handbook Nelson Thornes (publisher) This is Modern Art Matthew Collins A World of History of Art Honour and Fleming Ways of Seeing John Berger Art Now 4 Hans Werner Holzwarth Illustration Now Julius Wiedermann -

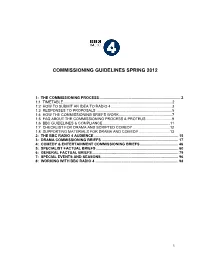

DN Master Doc COMMISSIONING GUIDELINES SPRING 2011

COMMISSIONING GUIDELINES SPRING 2012 1: THE COMMISSIONING PROCESS..............................................................................2 1:1 TIMETABLE.........................................................................................................2 1:2 HOW TO SUBMIT AN IDEA TO RADIO 4...........................................................3 1:3 RESPONSES TO PROPOSALS.........................................................................5 1:4 HOW THE COMMISSIONING BRIEFS WORK...................................................7 1:5 FAQ ABOUT THE COMMISSIONING PROCESS & PROTEUS.........................9 1:6 BBC GUIDELINES & COMPLIANCE.................................................................11 1:7 CHECKLIST FOR DRAMA AND SCRIPTED COMEDY....................................12 1:8 SUPPORTING MATERIALS FOR DRAMA AND COMEDY..............................13 2: THE BBC RADIO 4 AUDIENCE.................................................................................15 3: DRAMA COMMISSIONING BRIEFS..........................................................................17 4: COMEDY & ENTERTAINMENT COMMISSIONING BRIEFS.....................................46 5: SPECIALIST FACTUAL BRIEFS...............................................................................60 6: GENERAL FACTUAL BRIEFS...................................................................................79 7: SPECIAL EVENTS AND SEASONS...........................................................................96 8: WORKING WITH BBC RADIO 4................................................................................98 -

Art & Finance Report 2019

Art & Finance Report 2019 6th edition Se me Movió el Piso © Lina Sinisterra (2014) Collect on your Collection YOUR PARTNER IN ART FINANCING westendartbank.com RZ_WAB_Deloitte_print.indd 1 23.07.19 12:26 Power on your peace of mind D.KYC — Operational compliance delivered in managed services to the art and finance industry D.KYC (Deloitte Know Your Customer) is an integrated managed service that combines numerous KYC/AML/CTF* services, expertise, and workflow management. The service is supported by a multi-channel web-based platform and allows you to delegate the execution of predefined KYC/AML/CTF activities to Deloitte (Deloitte Solutions SàRL PSF, ISO27001 certified). www2.deloitte.com/lu/dkyc * KYC: Know Your Customer - AML/CTF: Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Empower your art activities Deloitte’s services within the Art & Finance ecosystem Deloitte Art & Finance assists financial institutions, art businesses, collectors and cultural stakeholders with their art-related activities. The Deloitte Art & Finance team has a passion for art and brings expertise in consulting, tax, audit and business intelligence to the global art market. www.deloitte-artandfinance.com © 2019 Deloitte Tax & Consulting dlawmember of the Deloitte Legal network The Art of Law DLaw – a law firm for the Art and Finance Industry At DLaw, a dedicated team of lawyers supports art collectors, dealers, auctioneers, museums, private banks and art investment funds at each stage of their project. www.dlaw.lu © 2019 dlaw Art & Finance Report 2019 | Table of contents Table of contents Foreword 14 Introduction 16 Methodology and limitations 17 External contributions 18 Deloitte CIS 21 Key report findings 2019 27 Priorities 31 The big picture: Art & Finance is an emerging industry 36 The role of Art & Finance within the cultural and creative sectors 40 Section 1. -

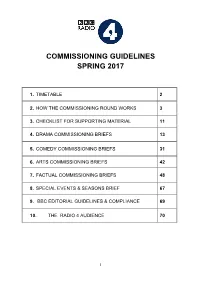

Commissioning Guidelines Spring 2017

COMMISSIONING GUIDELINES SPRING 2017 1. TIMETABLE 2 2. HOW THE COMMISSIONING ROUND WORKS 3 3. CHECKLIST FOR SUPPORTING MATERIAL 11 4. DRAMA COMMISSIONING BRIEFS 13 5. COMEDY COMMISSIONING BRIEFS 31 6. ARTS COMMISSIONING BRIEFS 42 7. FACTUAL COMMISSIONING BRIEFS 48 8. SPECIAL EVENTS & SEASONS BRIEF 67 9. BBC EDITORIAL GUIDELINES & COMPLIANCE 69 10. THE RADIO 4 AUDIENCE 70 1 1. TIMETABLE Drama and Comedy Guidelines published Week commencing 19 December Briefing in the Radio Theatre, London 30 January Proteus open for drama and comedy submissions Briefing in MediaCityUK, Salford 01 February Phase 1 deadline for pre-offers Midday 22 February Phase 1 results published in Proteus Week commencing 13 March Phase 2 deadline for final offers Midday 12 April Phase 2 results of final offers published in Proteus End of July Factual and Arts Guidelines published Week commencing 19 December Briefing in the Radio Theatre, London 20 February Proteus open for factual and arts submissions Briefing in MediaCityUK, Salford 22 February Phase 1 deadline for pre-offers and batch tenders Midday 09 March Phase 1 results published in Proteus Week commencing 03 April Phase 2 deadline for final offers Midday 11 May Phase 2 results of final offers and batch tenders End of July published in Proteus 2 2. HOW THE COMMISSIONING ROUND WORKS Everything in this commissioning round is open to competition. Any department or company with suitable expertise may submit proposals for any area of output. We are taking two distinct approaches to commissioning. Each of them has two phases. Specific ideas Drama and Comedy programmes – and some Factual programmes – are being commissioned in the traditional Radio 4 manner, in which we invite you to submit proposals for specific ideas. -

Godslastering, Discriminerende Uitingen Wegens Godsdienst En Haatuitingen

Godslastering, discriminerende uitingen wegens godsdienst en haatuitingen WWODC_248_12.inddODC_248_12.indd 1 222-3-20072-3-2007 111:32:541:32:54 WWODC_248_12.inddODC_248_12.indd 2 222-3-20072-3-2007 111:33:171:33:17 248 Onderzoek en beleid Godslastering, discriminerende uitingen wegens godsdienst en haatuitingen Een inventariserende studie B.A.M. van Stokkom H.J.B. Sackers J.-P. Wils Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek- en Documentatiecentrum WWODC_248_12.inddODC_248_12.indd SSec1:3ec1:3 222-3-20072-3-2007 111:33:171:33:17 Onderzoek en beleid De reeks Onderzoek en beleid omvat de rapporten van onderzoek dat door en in opdracht van het WODC is verricht. Opname in de reeks betekent niet dat de inhoud van de rapporten het standpunt van de Minister van Justitie weergeeft. Exemplaren van dit rapport kunnen worden besteld bij het distributiecentrum van Boom Juridische uitgevers: Boom distributiecentrum te Meppel Tel. 0522-23 75 55 Fax 0522-25 38 64 E-mail [email protected] Voor ambtenaren van het Ministerie van Justitie is een beperkt aantal gratis exemplaren beschikbaar. Deze kunnen worden besteld bij: Bibliotheek WODC, kamer KO 14 Postbus 20301, 2500 EH Den Haag Deze gratis levering geldt echter slechts zolang de voorraad strekt. De integrale tekst van de WODC-rapporten is gratis te downloaden van www.wodc.nl. Op www.wodc.nl is ook nadere informatie te vinden over andere WODC-publicaties. © 2007 WODC Behoudens de in of krachtens de Auteurswet van 1912 gestelde uitzonderingen mag niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch, door fotokopieën, opnamen of enige andere manier, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestem- ming van de uitgever.