Marx-Without-Myth-1975-Rubel.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncovering Marx's Yet Unpublished Writings

Uncovering Marx's Yet Unpublished Writings Kevin B. Anderson Published in Critique (Glasgow), No. 30-31 (1998), pp. 179-187 [reprinted in Marx, edited by Scott Meikle (Ashgate 2002); translated into Turkish in Insancil, Istanbul, May 1997] When Lawrence Krader published his historic transcription of Marx's Ethnological Notebooks 25 years ago, a new window was opened into Marx's thought. What in published form had become 250 pages of notes by Marx on Lewis Henry Morgan and other anthropologists which he had compiled in his last years, 1880-81, showed us as never before a Marx concerned as much with gender relations and with non-Western societies such as India, pre-Colombian Mexico, and the Australian aborigines, as well as ancient Ireland, as he was with the emancipation of the industrial proletariat. As will be shown below, to this day there are a significant number of writings by Marx on these and other issues which have never been published in any language. Why this is still the case in 1997, 114 years after Marx's death, is the subject of this essay, in which I will also take up plans now in progress in Europe to publish many of these writings for the first time. The problem really begins with Engels and continues today. While Engels labored long and hard to edit and publish what he considered to be a definitive edition of Vol. I of Capital in 1890, and brought out Vols. II and III of that work in 1885 and 1894 by carefully editing and arranging Marx's draft manuscripts, Engels did not plan or even propose the publication of the whole of Marx's writings. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49926-2 — Revolutionary Thought after the Paris Commune, 1871–1885 Julia Nicholls Excerpt More Information Introduction Following the defeat of the Paris Commune in late May , its partici- pants and supporters were frequently moved to declare that while ‘le cadavre est à terre ... l’idée est debout’: ‘the body may have fallen, but the idea still stands’. Historians, political commentators, and world leaders alike have advanced their own interpretations of the events of spring since the last shots were fired. What precisely ex- Communards believed this idea to be, however, has never been clear. This book addresses itself to this question. Through an exploration of the nature and content of French revolutionary thought from the years immediately following the Commune’s fall, it demonstrates that this idea was not a specific policy or doctrine. Rather, by extensively redefining familiar concepts and using their circumstances creatively, it was the idea of a distinct, united, and politically viable French revolutionary movement that activists sought to preserve. The relative success of these efforts, further- more, has significant implications for the ways in which scholars under- stand both the founding years of the French Third Republic and the nature of the modern revolutionary tradition. In the small hours of March , troops from the French Army marched into Paris. Their objective was the removal of a number of cannons that had formed part of the capital’s defence during the four- month-long Siege of Paris that brought to an end the Franco-Prussian War. News of the soldiers’ early morning arrival spread quickly through the working-class districts of Belleville, Buttes-Chaumont, and Montmartre where the artillery was being stored. -

1964 Jaargang 19 (Xix)

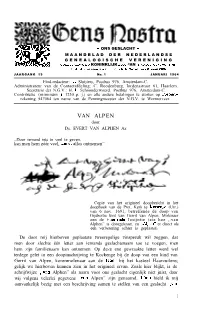

- ONS GESLACHT - MAANDBLAD DER NEDERLANDSE GENEALOGISCHE VERENIGING OOEDGEKEURD 312 KONINKLIJK BESL. “AN 16 A”O”STUS reaa. YO. 85 Llc.tstel,jk podpeKe”rd 51, KO”i”kli,k a.,,uit van J .+r,, ,833 JAARGANG 19 No. 1 JANUARI 1964 Eind-redacteur: J. Sluijters, Postbus 976, Amsterdam-C. Administrateur van de Contactafdeling: C. Roodenburg, Iordensstraat 61, Haarlem. Secretaris der N.G.V.: H. J. Schoonderwoerd, Postbus 976, Amsterdam-C. Contributie (minimum f 1230 p. j.) en alle andere betalingen te storten op Postgiro- rekening 547064 ten name van de Penningmeester der N.G.V. te Wormerveer. VAN ALPEN door Ds. EVERT VAN ALPHEN Az ,,Door iemand iets te veel te geven, kan men hem zéér veel, zoniet alles ontnemen” Copie van het origineel doopbericht in het doopboek van de Prot. Kerk te Kortenge (Utr.) van 6 nov. 1691, betreffende de doop van Gijsbertie kint van Gerrit van Alpen, Molenaer aen de Haer ende Josijntie (zie hoe ,,van Alphen” is doorgekrast, en ,,Alpen” er direct als een verbetering achter is geplaatst). De door mij hierboven geplaatste tweeregelige zinspreuk wil zeggen, dat men door slechts één letter aan iemands geslachtsnaam toe te voegen, men hem zijn familienaam kan ontnemen. Op deze ene gewraakte letter werd wel terdege gelet in een doopinschrijving te Kockenge bij de doop van een kind van Gerrit van Alpen, korenmolenaar aan de Haer bij het kasteel Haarzuilens; gelijk we hierboven kunnen zien in het origineel ervan. Zoals hier blijkt, is de schrijfwijze ,,van Alphen” als naam voor ons geslacht eigenlijk niet juist, daar wij volgens velerlei gegevens ,,van Alpen” zijn genaamd. -

Fonds Gabriel Deville (Xviie-Xxe Siècles)

Fonds Gabriel Deville (XVIIe-XXe siècles) Répertoire numérique détaillé de la sous-série 51 AP (51AP/1-51AP/9) (auteur inconnu), révisé par Ariane Ducrot et par Stéphane Le Flohic en 1997 - 2008 Archives nationales (France) Pierrefitte-sur-Seine 1955 - 2008 1 https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/IR/FRAN_IR_001830 Cet instrument de recherche a été encodé en 2012 par l'entreprise Numen dans le cadre du chantier de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales sur la base d'une DTD conforme à la DTD EAD (encoded archival description) et créée par le service de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales 2 Archives nationales (France) INTRODUCTION Référence 51AP/1-51AP/9 Niveau de description fonds Intitulé Fonds Gabriel Deville Date(s) extrême(s) XVIIe-XXe siècles Nom du producteur • Deville, Gabriel (1854-1940) • Doumergue, Gaston (1863-1937) Importance matérielle et support 9 cartons (51 AP 1-9) ; 1,20 mètre linéaire. Localisation physique Pierrefitte Conditions d'accès Consultation libre, sous réserve du règlement de la salle de lecture des Archives nationales. DESCRIPTION Type de classement 51AP/1-6. Collection d'autographes classée suivant la qualité du signataire : chefs d'État, gouvernants français depuis la Restauration, hommes politiques français et étrangers, écrivains, diplomates, officiers, savants, médecins, artistes, femmes. XVIIIe-XXe siècles. 51AP/7-8. Documents divers sur Puydarieux et le département des Haute-Pyrénées. XVIIe-XXe siècles. 51AP/8 (suite). Documentation sur la Première Guerre mondiale. 1914-1919. 51AP/9. Papiers privés ; notes de travail ; rapports sur les archives de la Marine et les bibliothèques publiques ; écrits et documentation sur les départements français de la Révolution (Mont-Tonnerre, Rhin-et-Moselle, Roer et Sarre) ; manuscrit d'une « Chronologie générale avant notre ère ». -

GERMAN IMMIGRANTS, AFRICAN AMERICANS, and the RECONSTRUCTION of CITIZENSHIP, 1865-1877 DISSERTATION Presented In

NEW CITIZENS: GERMAN IMMIGRANTS, AFRICAN AMERICANS, AND THE RECONSTRUCTION OF CITIZENSHIP, 1865-1877 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alison Clark Efford, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Doctoral Examination Committee: Professor John L. Brooke, Adviser Approved by Professor Mitchell Snay ____________________________ Adviser Professor Michael L. Benedict Department of History Graduate Program Professor Kevin Boyle ABSTRACT This work explores how German immigrants influenced the reshaping of American citizenship following the Civil War and emancipation. It takes a new approach to old questions: How did African American men achieve citizenship rights under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments? Why were those rights only inconsistently protected for over a century? German Americans had a distinctive effect on the outcome of Reconstruction because they contributed a significant number of votes to the ruling Republican Party, they remained sensitive to European events, and most of all, they were acutely conscious of their own status as new American citizens. Drawing on the rich yet largely untapped supply of German-language periodicals and correspondence in Missouri, Ohio, and Washington, D.C., I recover the debate over citizenship within the German-American public sphere and evaluate its national ramifications. Partisan, religious, and class differences colored how immigrants approached African American rights. Yet for all the divisions among German Americans, their collective response to the Revolutions of 1848 and the Franco-Prussian War and German unification in 1870 and 1871 left its mark on the opportunities and disappointments of Reconstruction. -

Clases Sociales Y Estado En El Pensamiento Marxista: Cuestiones De Método

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Programa de Posgrado en Estudios Latinoamericanos Taller de investigación: clases sociales y Estado en el pensamiento marxista: cuestiones de método Profesor: Matari Pierre Email: [email protected] Semestre 2021-1 (septiembre-diciembre 2020) 15 sesiones de 4 horas (jueves 16 a 20 horas) Objetivo general El análisis de las clases sociales y de las formas de Estado estructura el pensamiento social y político marxista. Sin embargo, estos conceptos no fueron claramente definidos ni por Marx ni por Engels. Los comentarios posteriores se apoyan en algún aspecto o aforismo de sus obras. De suerte que ambas nociones entrañan problemas de teoría y de método que tensan el marxismo desde sus orígenes: el determinismo económico del proceso histórico; la antropología subyacente a las definiciones de las clases y de sus relaciones recíprocas; la naturaleza específica de lo político y de las formas de Estado. El taller propone introducir y discutir estas tres cuestiones a partir de una selección de textos de representantes, comentaristas y críticos del pensamiento social y político marxista del siglo XX. El programa está organizado en dos grandes partes divididas en tres secciones cada una. Introducción (dos sesiones) Lecturas obligatorias: Eric J. Hobsbawm, “La contribución de Karl Marx a la historiografía”. Shlomo Avineri, El pensamiento social y político de Marx (capítulo I “Reconsideración de la filosofía política de Hegel). Jean-Paul Sartre, Cuestiones de método (primera parte “Marxismo y existencialismo”). Lecturas complementarias: Raymond Aron, Las etapas del pensamiento sociológico (“los equívocos de la sociología 1 marxista” extracto del capítulo 3). Tom Bottomore y Maximilien Rubel, “La sociología y la filosofía social de Marx”. -

Wittgenstein, Marx, and Language Criticism the Philosophies of Self-Conciousness

Wittgenstein, Marx, and Language Criticism The Philosophies of Self-Conciousness NORBERTO ABREU E SILVA NETO Preliminarily I must say this paper results from researches belonging to a larger project of study on Karl Marx’s philosophy I am carrying out, and that the bringing of Wittgenstein and Marx together here presented does not have the aim of trying to prove or to suggest Marx exerted upon Wittgenstein’s philosophy some kind of indirect or second hand influence. My idea is that since they developed their work in dialogue with the same philosophical traditions this fact would make it possible to find out ways of establishing continuity between their philosophies. So, in this work I will bring out some connections I am working on with the aim of trying to read Wittgenstein as a materialist philosopher. 1. The uses of philosophy During twenty years (1839-1859) Marx dedicated himself to systematic philosophical research and to meditation. In the Preface to his Criticism of Political Economy,1 he exposes an assessment he made of his intellectual development during this period. He declares that through his studies and the essays and other works written during these years he did not have the aim of outlining a new system of thought or a new philosophy, but that he simply was only searching for the conducting thread of his studies; and that the works he wrote were not for printing, but for his personal edification. And, particularly, about the writing of The German Ideology, he reports that, when he and Engels decided to write this book, they aimed at developing their common conception in opposition to the ideological views of German 1 Marx 1963, 271, 274. -

The Actuality of Critical Theory in the Netherlands, 1931-1994 By

The Actuality of Critical Theory in the Netherlands, 1931-1994 by Nicolaas Peter Barr Clingan A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Martin E. Jay, Chair Professor John F. Connelly Professor Jeroen Dewulf Professor David W. Bates Spring 2012 Abstract The Actuality of Critical Theory in the Netherlands, 1931-1994 by Nicolaas Peter Barr Clingan Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Martin E. Jay, Chair This dissertation reconstructs the intellectual and political reception of Critical Theory, as first developed in Germany by the “Frankfurt School” at the Institute of Social Research and subsequently reformulated by Jürgen Habermas, in the Netherlands from the mid to late twentieth century. Although some studies have acknowledged the role played by Critical Theory in reshaping particular academic disciplines in the Netherlands, while others have mentioned the popularity of figures such as Herbert Marcuse during the upheavals of the 1960s, this study shows how Critical Theory was appropriated more widely to challenge the technocratic directions taken by the project of vernieuwing (renewal or modernization) after World War II. During the sweeping transformations of Dutch society in the postwar period, the demands for greater democratization—of the universities, of the political parties under the system of “pillarization,” and of -

The Revolution of 1848 in the History of French Republicanism Samuel Hayat

The Revolution of 1848 in the History of French Republicanism Samuel Hayat To cite this version: Samuel Hayat. The Revolution of 1848 in the History of French Republicanism. History of Political Thought, Imprint Academic, 2015, 36 (2), pp.331-353. halshs-02068260 HAL Id: halshs-02068260 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02068260 Submitted on 14 Mar 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. History of Political Thought, vol. 36, n° 2, p. 331-353 PREPRINT. FINAL VERSION AVAILABLE ONLINE https://www.ingentaconnect.com/contentone/imp/hpt/2015/00000036/00000002/art00006 The Revolution of 1848 in the History of French Republicanism Samuel Hayat Abstract: The revolution of February 1848 was a major landmark in the history of republicanism in France. During the July monarchy, republicans were in favour of both universal suffrage and direct popular participation. But during the first months of the new republican regime, these principles collided, putting republicans to the test, bringing forth two conceptions of republicanism – moderate and democratic-social. After the failure of the June insurrection, the former prevailed. During the drafting of the Constitution, moderate republicanism was defined in opposition to socialism and unchecked popular participation. -

Salgado Munoz, Manuel (2019) Origins of Permanent Revolution Theory: the Formation of Marxism As a Tradition (1865-1895) and 'The First Trotsky'

Salgado Munoz, Manuel (2019) Origins of permanent revolution theory: the formation of Marxism as a tradition (1865-1895) and 'the first Trotsky'. Introductory dimensions. MRes thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/74328/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Origins of permanent revolution theory: the formation of Marxism as a tradition (1865-1895) and 'the first Trotsky'. Introductory dimensions Full name of Author: Manuel Salgado Munoz Any qualifications: Sociologist Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Master of Research School of Social & Political Sciences, Sociology Supervisor: Neil Davidson University of Glasgow March-April 2019 Abstract Investigating the period of emergence of Marxism as a tradition between 1865 and 1895, this work examines some key questions elucidating Trotsky's theoretical developments during the first decade of the XXth century. Emphasizing the role of such authors like Plekhanov, Johann Baptists von Schweitzer, Lenin and Zetkin in the developing of a 'Classical Marxism' that served as the foundation of the first formulation of Trotsky's theory of permanent revolution, it treats three introductory dimensions of this larger problematic: primitive communism and its feminist implications, the debate on the relations between the productive forces and the relations of production, and the first apprehensions of Marx's economic mature works. -

Dr. Marie Zakrzewska

DR. MARIE ZAKRZEWSKA. FUNERAL ORATION BY WILLIAM LLOYD GARRISON, AND HER OWN FAREWELL ADDRESS.' A large number of the friends of Dr. Marie Zakrzewska, the founder of the New England Hospital for Women and Children, gathered on May 15th in the chapel of the Massachusetts Crematory Society, off Walkhill street, Forest Hills, to pay a last tribute of respect to her memory. The service was as simple as possible, and was made most impressive by the reading of a farewell address to her friends, written by Dr. Zakrzewska in Feb- ruary, with the request that it be read at her funeral. The body reposed in a black broadcloth-covered casket, on which were laid a few green wreaths. The request that flowers be omitted was observed. The services opened as follows with an ORATION BY WILLIAM LLOYD GARRISON. "We are gathered this lovely spring afternoon to testify our respect and love for a dear friend. She has anticipated this occa- sion by preparing her own address, presently to be read by an- other. Being dead she yet speaketh. For this remarkable woman's strong individuality could not be veiled, and, regardless of conven- tional forms, she has elected to have this simple service without clerical aid. "She had no politic methods, no skill in concealing opinions that traversed those in vogue, but her manifest sincerity of soul attracted helpers whom policy would have repelled. Although not literally the first regular woman physician in Boston she was, par excellence, the head of the long line of educated women who adorn and dignify the ranks of the profession in this vicinity. -

Biographical Appendix

BIOGRAPHICAL APPENDIX Aberdeen George Hamilton-Gordon, earl of (1784–1860), was the Foreign Secretary under Robert Peel 1841–46 and a close friend of Guizot and of Princess Lieven. He acted as go- between for Louis-Philippe and the comte de Chambord in 1849–50. He was the Prime Minister of Great Britain in 1852–55. Affre Denis-Auguste (1793–1848) was the archbishop of Paris from 1840. He rallied to the Republic quickly in 1848 but was mortally wounded when he tried to parlay with insur- gents during the June Days. d’Agoult Marie (1805–76) published her Histoire de la Révolution de 1848 under the name of Daniel Stern. Arago François (1786–1853) was an astronomer and member of the Provisional Government and Executive Commission. Barante Prosper de (1782–1866) was a member of the Doctrinaires in the Restoration and prefect during the July Monarchy as well as ambassador in Turin and Saint Petersburg. Baroche Jules (1802–70) was the Minister of the Interior from March 1850, actively supported the electoral reform law of 31 May 1850. He resigned when Changarnier was dis- missed but was made Minister of Foreign Affairs in April 1851, only to resign in October in protest against the President’s attempt to revoke the law of 31 May. After the coup he became President of the Council of State. Barrot Odilon (1791–1873) was prefect of the Seine after the 1830 Revolution. He was leader of the Dynastic Opposition © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 299 C. Guyver, The Second French Republic 1848–1852, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-59740-3 300 BIOGRAPHICAL APPENDIX during the July Monarchy, and his banquet campaign for reform of the electoral system helped trigger the February Revolution of 1848.