SB KK IRZYK 16May2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette

www.ssoar.info Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kester, B. (2002). Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933). (Film Culture in Transition). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-317059 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de * pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Abram, David. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than- Human World. New York: Vintage Books, 1996. Print. Adelt, Leonhard. “Lesabéndio. Ein Asteroiden-Roman.” Rev. of Lesabéndio. Ein Asteroiden-Roman by Paul Scheerbart. Das litterarische Echo. 2 Jan. 1914. 650–52. Über Paul Scheerbart: Ed. Paul Kaltefleiter. Oldenburg 1998. 221–23. Print. Adorno, Theodor and Max Horkheimer. Dialektik der Aufklärung: Philosophische Fragmente. Frankfurt a.M.: Fischer, 2008. Print. Alcock, John. An Enthusiasm for Orchids: Sex and Deception in Plant Evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. Print. Alraune. Dir. Henrik Galeen. Perf. Brigitte Helm and Paul Wegener. Ama-Film, 1928. Film. “Alraune.” Rev. of Alraune. Lichtbild-Bühne. Feb. 1928. Filmportal. Web. 12 Aug. 2013. Andriopoulos, Stefan. “Occult Conspiracies: Spirits and Secret Societies in Schiller’s Ghost Seer.” New German Critique; Ngc. (2008): 65. ArticleFirst. Web. 10 Dec. 2014. Arnheim, Rudolf. “Das Blumenwunder (1926)” from Film als Kunst. Presse über den Film “Das Blumenwunder”. Archiv der Deutschen Kinemathek. Print. The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments. Chicago: Rand McNally and Co., 1914. Project Gutenberg. Web. 24 Apr. 2012. Asendorf, Christoph. Batteries of Life: The History of Things and Their Perception in Modernity. Trans. Don Reneau. Weimar and Now: German Cultural Criticism. Ed. Martin Jay and Anton Kaes. Berkeley: U of California P, 1993. Google Books. Web. 22 Jul. 2012. Bakke, Monika. “Art for Plant’s Sake? Questioning Human Imperialism in the Age of Biotech.” Parallax. 18.4 (2012): 9–25. Balázs, Béla. “Tanzdichtungen” Musikblätter der Anbruch. March 1926: 109–112. Internet Archive. Web. 2 Dec. 2013. Balázs, Béla. Der Sichtbare Mensch oder die Kultur des Films. -

Der Kinematograph (August 1932)

Kino vor 20 Jahren U.T. Unter den Linden. Kapellmeister: Richard Seiler. -n. Im Jahre 1922 ii er Buchhalter in dir seldorf eingetretei .otn 27. Juli bis einschließlich 2. August 1912. Musik-Piece Zentrale als Chefbuchhalter be¬ dem Transformator nur entnom¬ 1. De- Hafen von Marseille. rufen. Im Jahre 1926 siedelte men werden, wenn alle Regel¬ £in Städtebild. er mit der Südfilm-Zentrale schlitten von der Hellstellung 2. Matkenscherz. nach München und Anfang 1928 soeben auf die ersten Stufen Drama in zwei Akten. nach Berlin über. gelangt sind, also die Verdunke¬ 3. Die ewig lächelnde Dame. In der Aufsichtsratssitzung lung des Kinos bereits begon¬ Humoristische Szenen. vom 27. September 1928 wurde nen hat. Die Kinopraxis ergibt 4. Union-Woche. ihm Prokura erteilt und in der aber, daß die Regelschlilten Übersicht über die interessantesten aktueller Aufsichtsratssitzung vom 14. No¬ niemals alle gleichzeitig auf der¬ eignisse der Woche. vember 1930 wurde er zum selben Regelstufe stehen, son¬ Direktor-Stellvertreter ernannt. dern je nach dem Stück ein¬ 5. Kirdliche Vaterlandsliebe. Ein patriotisches Gedicht. Calm hat sich in diesen zehn gestellt und während der Spiel¬ Jahren nicht nur innerhalb der dauer zur Lichtveränderung hin- 6. Zigolo und das geheimnisvolle Schloß. Abenteuerliche Komödie. Südfilm eine geachtete und und herbewegt werden. Man wichtige Position erworoen. kann für die Einstellung der Re¬ 7. In Valcamonica. gelschlitten nach erfolgtem Be¬ Bilder aus Oberitalien. ginn der Verdunkelung die Er¬ 8. Moritz als Modernist. tung, Freundschaft und Wer fahrungen zugrunde legen, die Posse. Schätzung gefunden «ich in der Praxis bei Verwen¬ dung von Widerständen ergeben haben. Nicht nur für neue der Anschaffung nicht billiger struktion wurden störende Ge¬ Lichtspieltheater sind die Re¬ als bisherige Widerstände stel¬ räusche in den erwähnten italie¬ Südfilm ihm im Laufe der zehn geltransformatoren bedeutungs¬ len. -

Der Kinematograph (August 1931)

DAS AITESIE IILM FACH BUTT lii VERLAG SCHERL* BERLIN SW68 5. Jahrgang Berlin, den 1. August 1931 Nummer 175 Heros Huyras Ein offener Brief Wir haben vorgestern, ob man Vorauszchlungen 'chon damit man uns nicht durch umfangreiche Neu¬ orwirft, daß wir es an der engagements 'itigen Objektivität fehlen retten will. äßen, die oifiziöse Nachricht Drittens: Interessant er die Übernahme des erosfilm-Verleih in Leipzig zu welchem Prozentsatz durch den zweiten Vorsitzen¬ cie einzelnen Leihverträge den des Reichsverbandes durchschnittlich! getätigt wer¬ Deutscher Lichtspieltheater. den. insbesondere, ob Herrn Huyras, in der Form gebracht, wie sie unser Leip¬ unter fünfunddreißig ziger Korrespondent dem Prozent „Kinemalograph“ übermit¬ vermietet wird und ob in telte. diesem billigen Leihpreis das Wir gehen sicher nicht so sehnsüchtig herbeige¬ fehl, wenn wir annehmen, wünschte Beiprogramm nun daß diese Mitteilungen sozu¬ in so vorbildlichem Maß sagen offiziös ge wesen sind, eingeschlossen so daß wir uns zweifellos er¬ ist, daß hier einmal ein lauben dürfen, im Anschluß Theaterbesitzerverleih vor¬ an diese Bekanntmachangen bildlich wirken könnte. ein paar ganz konkrete Fragen Unsere Neugierde erstreckt an die Heros oder Herrn sich dann viertens wei¬ Huyras zu richten, deren Be¬ ter auf die Tatsache, oh die antwortung zweifellos zur Zusammenarbeit mit der Ge¬ Klärung der Situation ganz nossenschaft der mitteldeut¬ ■ heblich beitragen wird. schen Lichlspieitheaterbesit- * zer außerdem in Theaterbesitzern gemacht Wir fragen das nicht, weil einer zwangsweisen Ver¬ Erstens: Die Firma worden sind? uns diese Abmachungen von pflichtung Huyras — um eine Wendung Zweitens: Erfolgt diese seiten der Heros nicht ge¬ >m offiziösen Kommunique zur Abnahme aller Heros¬ Erfüllung der bereits bezahl¬ fallen, sondern wir wünschen zu übernehmen — über- filme besteht. -

Download File

Lotte Reiniger Lived: June 2, 1899 - June 19, 1981 Worked as: animator, assistant director, co-director, director, film actress, illustrator, screenwriter, special effects Worked In: Canada, Germany, Italy, United Kingdom: England by Frances Guerin, Anke Mebold Lotte Reiniger made over sixty films, of which eleven are considered lost and fifty to have survived. Of the surviving films for which she had full artistic responsibility, eleven were created in the silent period if the three-part Doktor Dolittle (1927-1928) is considered a single film. Reiniger is known to have worked on—or contributed silhouette sequences to—at least another seven films in the silent era, and a further nine in the sound era. Additionally, there is evidence of her involvement in a number of film projects that remained at conceptual or pre-production stages. Reiniger is best known for her pioneering silhouette films, in which paper and cardboard cut-out figures, weighted with lead, and hinged at the joints—the more complex the characters’ narrative role, the larger their range of movements, and therefore, the more hinges for the body—were hand-manipulated from frame to frame and shot via stop motion photography. The figures were placed on an animation table and usually lit from below. In some of her later sound films the figures were lit both from above and below, depending on the desired visual effect. Framed with elaborate backgrounds made from varying layers of translucent paper or colorful acetate foils for color films, Reiniger’s characters were created and animated with exceptional skill and precision. Reiniger’s early films ranged in length from brief shorts of less than 300 feet to Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed/The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1923-1926), a film that is arguably the first full-length animated feature and is thus considered to be among the milestones of cinema history. -

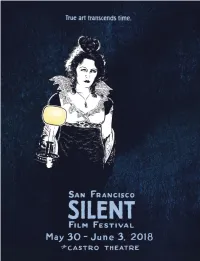

SFSFF 2018 Program Book

elcome to the San Francisco Silent Film Festival for five days and nights of live cinema! This is SFSFFʼs twenty-third year of sharing revered silent-era Wmasterpieces and newly revived discoveries as they were meant to be experienced—with live musical accompaniment. We’ve even added a day, so there’s more to enjoy of the silent-era’s treasures, including features from nine countries and inventive experiments from cinema’s early days and the height of the avant-garde. A nonprofit organization, SFSFF is committed to educating the public about silent-era cinema as a valuable historical and cultural record as well as an art form with enduring relevance. In a remarkably short time after the birth of moving pictures, filmmakers developed all the techniques that make cinema the powerful medium it is today— everything except for the ability to marry sound to the film print. Yet these films can be breathtakingly modern. They have influenced every subsequent generation of filmmakers and they continue to astonish and delight audiences a century after they were made. SFSFF also carries on silent cinemaʼs live music tradition, screening these films with accompaniment by the worldʼs foremost practitioners of putting live sound to the picture. Showcasing silent-era titles, often in restored or preserved prints, SFSFF has long supported film preservation through the Silent Film Festival Preservation Fund. In addition, over time, we have expanded our participation in major film restoration projects, premiering four features and some newly discovered documentary footage at this event alone. This year coincides with a milestone birthday of film scholar extraordinaire Kevin Brownlow, whom we celebrate with an onstage appearance on June 2. -

The Holy Gaze of Dr Caligari

The Holy Gaze of Dr Caligari Arash Chehelnabi Religious themes and motifs are an inherent aspect of Expressionist films from the 1920s and 1930s. Christian and Germanic metaphors of fate and destiny were among the most frequently used religious motifs in German expressionist cinema. Furthermore, sacrifice, suffering, redemption, and allusions to messianic heroism were central to the cinematic narratives. After the tragedy of the Great War, with its millions dead, wounded, or psychologically scarred, practices such as psychoanalysis, dream therapy, the Occult, and alternative spiritualities became fashionable concerns and interests in European society. Expressionism, which began as a visual arts movement before the Great War, rose in popularity as a cinematic genre after the four-year global conflict. The emphasis on religious symbolism, spirituality, and fable, meant that expressionistic films were appropriately suited to religious themes. German paganism coupled with Roman Catholic and Protestant Christianity, made for a rich syncretistic mix of religious symbols and themes that were indicative of post-war Europe. Religious themes were foremost in the minds of writers and directors during this time, with the production of classic expressionistic films such as Metropolis,1 Nosferatu,2 and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.3 The genre of European expressionism began prior to the commencement of the First World War. Originating as a visual arts movement, expressionism progressively influenced the disciplines of music, architecture, theatre, and -

La Réception Du Cinéma Allemand Par La Presse Cinématographique Française Entre 1921 Et 1933 Marc Lavastrou

La réception du cinéma allemand par la presse cinématographique française entre 1921 et 1933 Marc Lavastrou To cite this version: Marc Lavastrou. La réception du cinéma allemand par la presse cinématographique française entre 1921 et 1933. Linguistique. Université Toulouse le Mirail - Toulouse II, 2012. Français. NNT : 2012TOU20136. tel-00793003 HAL Id: tel-00793003 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00793003 Submitted on 21 Feb 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. § THESE Université de Toulouse En vue de l'obtention du DOCTORAT DE L'UNIVERSITÉ DE TOULOUSE Délivré par: UniversitéToulouse 2 Le Mirail(UT2 Le Mirail) Cotutelle internataonale avec : Présentée et soutenue par: Marc LAVASTROU Le '12 Décembre 2012 Titre: La réception du cinéma allemand par la presse cinématographique française entre 1921 et 1933 ED ALLPH@: Allemand Unité de recherche: CREG Directeur(s) de Thèse: M. André COMBES (Pr. - UniversitéToulouse 2 - Le Mirail) Rapporteurs: Mme Elizabeth GUILHAMON (Pr. - Université Michelde Montaigne - Bordeaux 3) Mme Anne LAGNY (Pr - ENS Lyon) Autre(s) membre(s) du jury: Mme Françoise KNOPPER (Pr. - UniversitéToulouse 2 - Le Mirail) Mme Valérie CARRÉ (MCF - Université de Strasbourg) La réception du cinéma allemand par la presse cinématographique française entre 1921 et 1933 1 INTRODUCTION 2 De part et d'autre du Rhin, les conséquences directes de la Première Guerre mondiale sont difficiles à surmonter. -

An Accident of Resistance in Nazi Germany: Oskar Kalbus's Three-Volume History of German Film (1935–37) Joel Westerdale Smith College, [email protected]

Masthead Logo Smith ScholarWorks German Studies: Faculty Publications German Studies Summer 2017 An Accident of Resistance in Nazi Germany: Oskar Kalbus's Three-Volume History of German Film (1935–37) Joel Westerdale Smith College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/ger_facpubs Part of the German Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Westerdale, Joel, "An Accident of Resistance in Nazi Germany: Oskar Kalbus's Three-Volume History of German Film (1935–37)" (2017). German Studies: Faculty Publications, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/ger_facpubs/1 This Article has been accepted for inclusion in German Studies: Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] RE-READINGS JOEL WESTERDALE An Accident of Resistance in Nazi Germany: Oskar Kalbus’s Three-Volume History of German Film (1935–37) ABSTRACT: This article reconsiders the first comprehensive history of German film, Oskar Kalbus’s two-volume Vom Werden deutscher Filmkunst (On the Rise of German Film Art, 1935) in terms of its contemporary reception in Nazi Germany and in light of a newly surfaced third volume. This is the first article dedicated to a work that scholars have long cited, though rarely without suspicion. The newly surfaced typescript for Der Film im Dritten Reich (Film in the Third Reich, 1937) confirms the author’s National Socialist sympathies, but at the same time it highlights by contrast the virtues of the two published volumes. KEYWORDS: film historiography, German film, Third Reich, cigarette albums, antisemitism Siegfried Kracauer’s From Caligari to Hitler (1947) continues to exert extraordinary influence on the discourse of German cinema before 1933. -

The Astrological Imaginary in Early Twentieth–Century German Culture

The Astrological Imaginary in Early Twentieth–Century German Culture by Jennifer Lynn Zahrt A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in German and the Designated Emphasis in Film in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Niklaus Largier, Co-Chair Professor Anton Kaes, Co-Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Spring 2012 ©2012 Jennifer Lynn Zahrt, All Rights Reserved. Abstract The Astrological Imaginary in Early Twentieth–Century German Culture by Jennifer Lynn Zahrt Doctor of Philosophy in German and the Designated Emphasis in Film University of California, Berkeley Professor Niklaus Largier, Co-Chair Professor Anton Kaes, Co-Chair My dissertation focuses on astrological discourses in early twentieth–century Germany. In four chapters, I examine films, literary texts, and selected academic and intellectual prose that engage astrology and its symbolism as a response to the experience of modernity in Germany. Often this response is couched within the context of a return to early modern German culture, the historical period when astrology last had popular validity. Proceeding from the understanding of astrology as a multiplicity of practices with their own histories, my dissertation analyzes the specific forms of astrological discourse that are taken up in early twentieth–century German culture. In my first chapter I examine the revival of astrology in Germany from the perspective of Oscar A. H. Schmitz (1873–1931), who galvanized a community of astrologers to use the term Erfahrungswissenschaft to promote astrology diagnostically, as an art of discursive subject formation. In my second chapter, I discuss how Paul Wegener’s Golem film cycle both responds to and intensifies the astrological and the occult revivals. -

Book-59415.Pdf

Ward_fm 1/8/01 2:41 PM Page i Weimar Surfaces Ward_fm 1/8/01 2:41 PM Page ii Ward_fm 1/8/01 2:41 PM Page iii Weimar and Now: German Cultural Criticism Edward Dimendberg, Martin Jay, and Anton Kaes, General Editors 1. Heritage of Our Times, by Ernst Bloch 2. The Nietzsche Legacy in Germany, 1890–1990, by Steven E. Aschheim 3. The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, edited by Anton Kaes, Martin Jay, and Edward Dimendberg 4. Batteries of Life: On the History of Things and Their Perception in Modernity, by Christoph Asendorf 5. Profane Illumination: Walter Benjamin and the Paris of Surrealist Revolution, by Margaret Cohen 6. Hollywood in Berlin: American Cinema and Weimar Germany,by Thomas J. Saunders 7. Walter Benjamin: An Aesthetic of Redemption, by Richard Wolin 8. The New Typography, by Jan Tschichold, translated by Ruari McLean 9. The Rule of Law under Siege: Selected Essays of Franz L. Neumann and Otto Kirchheimer, edited by William E. Scheuerman 10. The Dialectical Imagination: A History of the Frankfurt School and the Institute of Social Research, 1923–1950, by Martin Jay 11. Women in the Metropolis: Gender and Modernity in Weimar Cul- ture, edited by Katharina von Ankum 12. Letters of Heinrich and Thomas Mann, 1900–1949, edited by Hans Wysling, translated by Don Reneau 13. Empire of Ecstasy: Nudity and Movement in German Body Culture, 1910–1935, by Karl Toepfer 14. In the Shadow of Catastrophe: German Intellectuals between Apoca- lypse and Enlightenment, by Anson Rabinbach 15. Walter Benjamin’s Other History: Of Stones, Animals, Human Beings, and Angels, by Beatrice Hanssen 16. -

0317.1.00.Pdf

siting futurity Before you start to read this book, take this moment to think about making a donation to punctum books, an independent non-profit press, @ https://punctumbooks.com/support/ If you’re reading the e-book, you can click on the image below to go directly to our donations site. Any amount, no matter the size, is appreciated and will help us to keep our ship of fools afloat. Contri- butions from dedicated readers will also help us to keep our commons open and to cultivate new work that can’t find a welcoming port elsewhere. Our ad- venture is not possible without your support. Vive la Open Access. Fig. 1. Hieronymus Bosch, Ship of Fools (1490–1500) Siting Futurity: The “Feel Good” Tactical Radicalism of Contemporary Culture in and around Vienna. Copyright © 2021 by Susan Ingram. This work carries a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license, which means that you are free to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and you may also remix, transform and build upon the material, as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors (but not in a way that suggests the authors or punctum books endorses you and your work), you do not use this work for commercial gain in any form whatsoever, and that for any remixing and transformation, you distribute your rebuild under the same license. http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ First published in 2021 by punctum books, Earth, Milky Way. https://punctumbooks.com ISBN-13: 978-1-953035-47-9 (print) ISBN-13: 978-1-953035-48-6 (ePDF) doi: 10.21983/P3.0317.1.00 lccn: 2021935512 Library of Congress Cataloging Data is available from the Library of Congress Book Design: Vincent W.J.