RHYTHM and REFRAIN.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

Index Abulfeda crater chain (Moon), 97 Aphrodite Terra (Venus), 142, 143, 144, 145, 146 Acheron Fossae (Mars), 165 Apohele asteroids, 353–354 Achilles asteroids, 351 Apollinaris Patera (Mars), 168 achondrite meteorites, 360 Apollo asteroids, 346, 353, 354, 361, 371 Acidalia Planitia (Mars), 164 Apollo program, 86, 96, 97, 101, 102, 108–109, 110, 361 Adams, John Couch, 298 Apollo 8, 96 Adonis, 371 Apollo 11, 94, 110 Adrastea, 238, 241 Apollo 12, 96, 110 Aegaeon, 263 Apollo 14, 93, 110 Africa, 63, 73, 143 Apollo 15, 100, 103, 104, 110 Akatsuki spacecraft (see Venus Climate Orbiter) Apollo 16, 59, 96, 102, 103, 110 Akna Montes (Venus), 142 Apollo 17, 95, 99, 100, 102, 103, 110 Alabama, 62 Apollodorus crater (Mercury), 127 Alba Patera (Mars), 167 Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), 110 Aldrin, Edwin (Buzz), 94 Apophis, 354, 355 Alexandria, 69 Appalachian mountains (Earth), 74, 270 Alfvén, Hannes, 35 Aqua, 56 Alfvén waves, 35–36, 43, 49 Arabia Terra (Mars), 177, 191, 200 Algeria, 358 arachnoids (see Venus) ALH 84001, 201, 204–205 Archimedes crater (Moon), 93, 106 Allan Hills, 109, 201 Arctic, 62, 67, 84, 186, 229 Allende meteorite, 359, 360 Arden Corona (Miranda), 291 Allen Telescope Array, 409 Arecibo Observatory, 114, 144, 341, 379, 380, 408, 409 Alpha Regio (Venus), 144, 148, 149 Ares Vallis (Mars), 179, 180, 199 Alphonsus crater (Moon), 99, 102 Argentina, 408 Alps (Moon), 93 Argyre Basin (Mars), 161, 162, 163, 166, 186 Amalthea, 236–237, 238, 239, 241 Ariadaeus Rille (Moon), 100, 102 Amazonis Planitia (Mars), 161 COPYRIGHTED -

Amplifying Factors Leading to the Collapse of Primary Producers

Amplifying factors leading to the collapse of primary producers during the Chicxulub impact and Deccan Traps eruptions Guillaume Le Hir, Frédéric Fluteau, Baptiste Suchéras-Marx, Yves Godderis To cite this version: Guillaume Le Hir, Frédéric Fluteau, Baptiste Suchéras-Marx, Yves Godderis. Amplifying factors leading to the collapse of primary producers during the Chicxulub impact and Deccan Traps erup- tions. Mass Extinctions, Volcanism, and Impacts: New Developments, 544, pp.223-245, 2020, 10.1130/2020.2544(09). hal-03164650 HAL Id: hal-03164650 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03164650 Submitted on 30 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License Amplifying Factors Leading to the Collapse of Primary Producers during the Chicxulub Impact and Deccan Traps 5 by Le Hir G., Fluteau F., Sucheras B. and Goddéris Y. Abstract 10 The latest Cretaceous (K; Maastrichtian) through earliest Paleogene (Pg; Danian) interval is a time marked by one of five major mass extinctions in the Earth’s history. The synthesis of published data permits the temporal correlation of the K-Pg boundary crisis with two major geological events: 1) the Chicxulub impact discovered in the Yucatán peninsula (Mexico) and 2) the Deccan Traps located on the west-central India plateau. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette

www.ssoar.info Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kester, B. (2002). Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933). (Film Culture in Transition). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-317059 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de * pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. -

2017 Fall Event Brochure

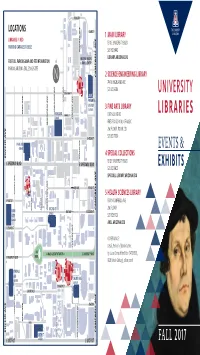

RING RD LOCATIONS ELM ST 1 MAIN LIBRARY LIBRARIES IN RED 1510 E UNIVERSITY BLVD PARKING GARAGES IN BLUE WARREN AVE WARREN 520.621.6442 ARIZONA HEALTH LIBRARY.ARIZONA.EDU FOR FULL PARKING MAP AND FEE INFORMATION SCIENCES CENTER PARKING.ARIZONA.EDU, 520.626.7275 CAMPBELL AVE CAMPBELL 2 SCIENCE-ENGINEERING LIBRARY 744 N HIGHLAND AVE 520.621.6384 E DRACHMAN ST UAMC VINE AVE PATIENT & VISITOR GARAGE 3 FINE ARTS LIBRARY HIGHLAND AVE PARK AVE PARK HIGHLAND E MABEL ST 1017 N OLIVE RD GARAGE AVE CHERRY FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC MOUNTAIN AVE MOUNTAIN 2nd FLOOR, ROOM 233 E HELEN ST 520.621.7009 PARK AVE GARAGE 4 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS EUCLID AVE WARREN AVE WARREN 1510 E UNIVERSITY BLVD E SPEEDWAY BLVD E SPEEDWAY BLVD 520.621.6423 SPECCOLL.LIBRARY.ARIZONA.EDU ONE WAY E FIRST ST MUSIC TYNDALL AVE TYNDALL BLDG 5 HEALTH SCIENCES LIBRARY E FIRST ST 1501 N CAMPBELL AVE MOUNTAIN AVE MOUNTAIN CAMPBELL AVE CAMPBELL PALM DR PALM OLIVE RD SECOND ST 2nd FLOOR MAIN ONE WAY E SECOND ST GATE GARAGE 520.626.6125 GARAGE AHSL.ARIZONA.EDU E SECOND ST COVER IMAGE: CHERRY AVE CHERRY Detail, Portrait of Martin Luther, OLD MALL CLOSED TO TRAFFIC E UNIVERSITY BLVD by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553), MAIN E UNIVERSITY BLVD 1528 (Veste Coburg), oil on panel TYNDALL AVE GARAGE CHERRY AVE GARAGE E FOURTH ST E FOURTH ST CHERRY AVE CHERRY ENKE DR TYNDALL AVE TYNDALL PARK AVE PARK LOWELL CAMPBELL AVE CAMPBELL EUCLID AVE NAT’L CHAMPIONS DR CHAMPIONS NAT’L SIXTH ST HIGHLAND AVE E SIXTH ST GARAGE E SIXTH ST FALL 2017 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS SPECIAL EVENTS speccoll.library.arizona.edu Library Cats Tech Breakfast Contact: Kathy McCarthy | 520.626.8332 Saturday, October 28, 9–11 a.m., Science-Engineering Library [email protected] All alumni and friends are welcome at our Homecoming EXHIBIT | Opens August 7 celebration. -

ELEMENTARY ART Integrated Within the Regular Classroom Linda Fleetwood NEISD Visual Art Director WAYS ART TAUGHT WITHIN NEISD

ELEMENTARY ART Integrated Within the Regular Classroom Linda Fleetwood NEISD Visual Art Director WAYS ART TAUGHT WITHIN NEISD • Woven into regular elementary classes – integration • Instructional Assistants specializing in art – taught within rotation • Parents/Volunteers – usually after school • Art Clubs sponsored by elementary teachers – usually after school • Certified Art Teachers (2) – Castle Hills Elementary & Montgomery Elementary ELEMENTARY LESSON DESIGNS • NEISD Visual Art Webpage (must be logged in) https://www.neisd.net/Page/687 to find it open NEISD website > Departments > Fine Arts > Visual Art on left • Curriculum Available K-5 • Elementary Art TEKS • Lesson Designs (listed by topic and grade level) SOURCES FOR LESSON DESIGNS • Pinterest https://www.pinterest.com/ • YouTube • Art to Remember https://arttoremember.com/lesson-plans/ • SAX/School Specialty (an art supply source) https://www.schoolspecialty.com/ideas- resources/lesson-plans#pageView:list • Blick Lesson Plans (an art supply source) https://www.dickblick.com/lesson-plans/ LESSON TODAY, GRADES K-1 • Gr K-1, “Kitty Cat with Her Bird” • Integrate with Math Shapes • Based on Paul Klee • Discussion: Book The Cat and the Bird by Geraldine Elschner & Peggy Nile and watch the “How To” video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tW6MmY4xPe8 • Artwork: Cat and Bird, 1928 LESSON TODAY, GRADES 2-3 • Gr 2-3, “Me, On Top of Colors” • Integrate with Social Studies with Personal Identity, Math Shapes • Based on Paul Klee • Discussion: Poem Be Glad Your Nose Is On Your Face by Jack -

Discovering the Lost Race Story: Writing Science Fiction, Writing Temporality

Discovering the Lost Race Story: Writing Science Fiction, Writing Temporality This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia 2008 Karen Peta Hall Bachelor of Arts (Honours) Discipline of English and Cultural Studies School of Social and Cultural Studies ii Abstract Genres are constituted, implicitly and explicitly, through their construction of the past. Genres continually reconstitute themselves, as authors, producers and, most importantly, readers situate texts in relation to one another; each text implies a reader who will locate the text on a spectrum of previously developed generic characteristics. Though science fiction appears to be a genre concerned with the future, I argue that the persistent presence of lost race stories – where the contemporary world and groups of people thought to exist only in the past intersect – in science fiction demonstrates that the past is crucial in the operation of the genre. By tracing the origins and evolution of the lost race story from late nineteenth-century novels through the early twentieth-century American pulp science fiction magazines to novel-length narratives, and narrative series, at the end of the twentieth century, this thesis shows how the consistent presence, and varied uses, of lost race stories in science fiction complicates previous critical narratives of the history and definitions of science fiction. In examining the implicit and explicit aspects of temporality and genre, this thesis works through close readings of exemplar texts as well as historicist, structural and theoretically informed readings. It focuses particularly on women writers, thus extending previous accounts of women’s participation in science fiction and demonstrating that gender inflects constructions of authority, genre and temporality. -

Fall 2016 Spotlight Newsletter

Newsletter Issue 3 - Fall 2016 Spotlight on a Shared Sense of Purpose By Dr. James Bell, Dean of Faculty erated by the close connection that we picture on page 35. And those are While the phrase “a rising tide share. only a few of the pictures. lift s all boats” is most commonly as- Of course, some of this interac- Many of the stories in this semes- sociated with JFK and economics, this tion is a consequence of our small ter’s newsletter describe eff orts and aphorism—which Kennedy speech- size and limited faculty and student events that brought us all together writer Ted Sorensen confi rms did not population, but those factors don’t to celebrate and labor and play. Th ey originate with him or the president— account for the genuine camaraderie also highlight the role of alumni and has applications far beyond econom- that characterizes life at Northwest- community members who use their ics. In fact, the phrase came to mind ern. Look at student Charlie Wylie talents and resources to support our as I read through this fall’s Spotlight and instructor Dawn Allen playing students’ eff orts. And—as always— and noted how many stories center on whatever that is they are playing on they showcase the skills and knowl- collaboration and interaction among page 7, check out Northwestern stu- edge that our faculty members bring faculty (within and among depart- dent teachers posing with high school to their classes each day. ments), students, administrators, students as part of a grant-funded We have many things to celebrate, alumni, and our community. -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

Picturing France

Picturing France Classroom Guide VISUAL ARTS PHOTOGRAPHY ORIENTATION ART APPRECIATION STUDIO Traveling around France SOCIAL STUDIES Seeing Time and Pl ace Introduction to Color CULTURE / HISTORY PARIS GEOGRAPHY PaintingStyles GOVERNMENT / CIVICS Paris by Night Private Inve stigation LITERATURELANGUAGE / CRITICISM ARTS Casual and Formal Composition Modernizing Paris SPEAKING / WRITING Department Stores FRENCH LANGUAGE Haute Couture FONTAINEBLEAU Focus and Mo vement Painters, Politics, an d Parks MUSIC / DANCENATURAL / DRAMA SCIENCE I y Fontainebleau MATH Into the Forest ATreebyAnyOther Nam e Photograph or Painting, M. Pa scal? ÎLE-DE-FRANCE A Fore st Outing Think L ike a Salon Juror Form Your Own Ava nt-Garde The Flo ating Studio AUVERGNE/ On the River FRANCHE-COMTÉ Stream of Con sciousness Cheese! Mountains of Fra nce Volcanoes in France? NORMANDY “I Cannot Pain tan Angel” Writing en Plein Air Culture Clash Do-It-Yourself Pointillist Painting BRITTANY Comparing Two Studie s Wish You W ere Here Synthétisme Creating a Moo d Celtic Culture PROVENCE Dressing the Part Regional Still Life Color and Emo tion Expressive Marks Color Collectio n Japanese Prin ts Legend o f the Château Noir The Mistral REVIEW Winds Worldwide Poster Puzzle Travelby Clue Picturing France Classroom Guide NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON page ii This Classroom Guide is a component of the Picturing France teaching packet. © 2008 Board of Trustees of the National Gallery of Art, Washington Prepared by the Division of Education, with contributions by Robyn Asleson, Elsa Bénard, Carla Brenner, Sarah Diallo, Rachel Goldberg, Leo Kasun, Amy Lewis, Donna Mann, Marjorie McMahon, Lisa Meyerowitz, Barbara Moore, Rachel Richards, Jennifer Riddell, and Paige Simpson. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Abram, David. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than- Human World. New York: Vintage Books, 1996. Print. Adelt, Leonhard. “Lesabéndio. Ein Asteroiden-Roman.” Rev. of Lesabéndio. Ein Asteroiden-Roman by Paul Scheerbart. Das litterarische Echo. 2 Jan. 1914. 650–52. Über Paul Scheerbart: Ed. Paul Kaltefleiter. Oldenburg 1998. 221–23. Print. Adorno, Theodor and Max Horkheimer. Dialektik der Aufklärung: Philosophische Fragmente. Frankfurt a.M.: Fischer, 2008. Print. Alcock, John. An Enthusiasm for Orchids: Sex and Deception in Plant Evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. Print. Alraune. Dir. Henrik Galeen. Perf. Brigitte Helm and Paul Wegener. Ama-Film, 1928. Film. “Alraune.” Rev. of Alraune. Lichtbild-Bühne. Feb. 1928. Filmportal. Web. 12 Aug. 2013. Andriopoulos, Stefan. “Occult Conspiracies: Spirits and Secret Societies in Schiller’s Ghost Seer.” New German Critique; Ngc. (2008): 65. ArticleFirst. Web. 10 Dec. 2014. Arnheim, Rudolf. “Das Blumenwunder (1926)” from Film als Kunst. Presse über den Film “Das Blumenwunder”. Archiv der Deutschen Kinemathek. Print. The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments. Chicago: Rand McNally and Co., 1914. Project Gutenberg. Web. 24 Apr. 2012. Asendorf, Christoph. Batteries of Life: The History of Things and Their Perception in Modernity. Trans. Don Reneau. Weimar and Now: German Cultural Criticism. Ed. Martin Jay and Anton Kaes. Berkeley: U of California P, 1993. Google Books. Web. 22 Jul. 2012. Bakke, Monika. “Art for Plant’s Sake? Questioning Human Imperialism in the Age of Biotech.” Parallax. 18.4 (2012): 9–25. Balázs, Béla. “Tanzdichtungen” Musikblätter der Anbruch. March 1926: 109–112. Internet Archive. Web. 2 Dec. 2013. Balázs, Béla. Der Sichtbare Mensch oder die Kultur des Films. -

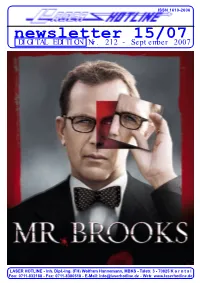

Newsletter 15/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 15/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 212 - September 2007 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 15/07 (Nr. 212) September 2007 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, schen und japanischen DVDs Aus- Nach den in diesem Jahr bereits liebe Filmfreunde! schau halten, dann dürfen Sie sich absolvierten Filmfestivals Es gibt Tage, da wünscht man sich, schon auf die Ausgaben 213 und ”Widescreen Weekend” (Bradford), mit mindestens fünf Armen und 214 freuen. Diese werden wir so ”Bollywood and Beyond” (Stutt- mehr als nur zwei Hirnhälften ge- bald wie möglich publizieren. Lei- gart) und ”Fantasy Filmfest” (Stutt- boren zu sein. Denn das würde die der erfordert das Einpflegen neuer gart) steht am ersten Oktober- tägliche Arbeit sicherlich wesent- Titel in unsere Datenbank gerade wochenende das vierte Highlight lich einfacher machen. Als enthu- bei deutschen DVDs sehr viel mehr am Festivalhimmel an. Nunmehr siastischer Filmfanatiker vermutet Zeit als bei Übersee-Releases. Und bereits zum dritten Mal lädt die man natürlich schon lange, dass Sie können sich kaum vorstellen, Schauburg in Karlsruhe zum irgendwo auf der Welt in einem was sich seit Beginn unserer Som- ”Todd-AO Filmfestival” in die ba- kleinen, total unauffälligen Labor merpause alles angesammelt hat! dische Hauptstadt ein. Das diesjäh- inmitten einer Wüstenlandschaft Man merkt deutlich, dass wir uns rige Programm wurde gerade eben bereits mit genmanipulierten Men- bereits auf das Herbst- und Winter- offiziell verkündet und das wollen schen experimentiert wird, die ge- geschäft zubewegen.