Discovering the Lost Race Story: Writing Science Fiction, Writing Temporality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wallace Berman Aleph

“Art is Love is God”: Wallace Berman and the Transmission of Aleph, 1956-66 by Chelsea Ryanne Behle B.A. Art History, Emphasis in Public Art and Architecture University of San Diego, 2006 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2012 ©2012 Chelsea Ryanne Behle. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: __________________________________________________ Department of Architecture May 24, 2012 Certified by: __________________________________________________________ Caroline Jones, PhD Professor of the History of Art Thesis Supervisor Accepted by:__________________________________________________________ Takehiko Nagakura Associate Professor of Design and Computation Chair of the Department Committee on Graduate Students Thesis Supervisor: Caroline Jones, PhD Title: Professor of the History of Art Thesis Reader 1: Kristel Smentek, PhD Title: Class of 1958 Career Development Assistant Professor of the History of Art Thesis Reader 2: Rebecca Sheehan, PhD Title: College Fellow in Visual and Environmental Studies, Harvard University 2 “Art is Love is God”: Wallace Berman and the Transmission of Aleph, 1956-66 by Chelsea Ryanne Behle Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 24, 2012 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies ABSTRACT In 1956 in Los Angeles, California, Wallace Berman, a Beat assemblage artist, poet and founder of Semina magazine, began to make a film. -

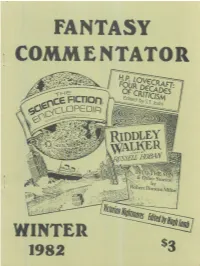

Fantasy Commentator EDITOR and PUBLISHER: CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: A

Fantasy Commentator EDITOR and PUBLISHER: CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: A. Langley Searles Lee Becker, T. G. Cockcroft, 7 East 235th St. Sam Moskowitz, Lincoln Bronx, N. Y. 10470 Van Rose, George T. Wetzel Vol. IV, No. 4 -- oOo--- Winter 1982 Articles Needle in a Haystack Joseph Wrzos 195 Voyagers Through Infinity - II Sam Moskowitz 207 Lucky Me Stephen Fabian 218 Edward Lucas White - III George T. Wetzel 229 'Plus Ultra' - III A. Langley Searles 240 Nicholls: Comments and Errata T. G. Cockcroft and 246 Graham Stone Verse It's the Same Everywhere! Lee Becker 205 (illustrated by Melissa Snowind) Ten Sonnets Stanton A. Coblentz 214 Standing in the Shadows B. Leilah Wendell 228 Alien Lee Becker 239 Driftwood B. Leilah Wendell 252 Regular Features Book Reviews: Dahl's "My Uncle Oswald” Joseph Wrzos 221 Joshi's "H. P. L. : 4 Decades of Criticism" Lincoln Van Rose 223 Wetzel's "Lovecraft Collectors Library" A. Langley Searles 227 Moskowitz's "S F in Old San Francisco" A. Langley Searles 242 Nicholls' "Science Fiction Encyclopedia" Edward Wood 245 Hoban's "Riddley Walker" A. Langley Searles 250 A Few Thorns Lincoln Van Rose 200 Tips on Tales staff 253 Open House Our Readers 255 Indexes to volume IV 266 This is the thirty-second number of Fantasy Commentator^ a non-profit periodical of limited circulation devoted to articles, book reviews and verse in the area of sci ence - fiction and fantasy, published annually. Subscription rate: $3 a copy, three issues for $8. All opinions expressed herein are the contributors' own, and do not necessarily reflect those of the editor or the staff. -

The Satanic Rituals Anton Szandor Lavey

The Rites of Lucifer On the altar of the Devil up is down, pleasure is pain, darkness is light, slavery is freedom, and madness is sanity. The Satanic ritual cham- ber is die ideal setting for the entertainment of unspoken thoughts or a veritable palace of perversity. Now one of the Devil's most devoted disciples gives a detailed account of all the traditional Satanic rituals. Here are the actual texts of such forbidden rites as the Black Mass and Satanic Baptisms for both adults and children. The Satanic Rituals Anton Szandor LaVey The ultimate effect of shielding men from the effects of folly is to fill the world with fools. -Herbert Spencer - CONTENTS - INTRODUCTION 11 CONCERNING THE RITUALS 15 THE ORIGINAL PSYCHODRAMA-Le Messe Noir 31 L'AIR EPAIS-The Ceremony of the Stifling Air 54 THE SEVENTH SATANIC STATEMENT- Das Tierdrama 76 THE LAW OF THE TRAPEZOID-Die elektrischen Vorspiele 106 NIGHT ON BALD MOUNTAIN-Homage to Tchort 131 PILGRIMS OF THE AGE OF FIRE- The Statement of Shaitan 151 THE METAPHYSICS OF LOVECRAFT- The Ceremony of the Nine Angles and The Call to Cthulhu 173 THE SATANIC BAPTISMS-Adult Rite and Children's Ceremony 203 THE UNKNOWN KNOWN 219 The Satanic Rituals INTRODUCTION The rituals contained herein represent a degree of candor not usually found in a magical curriculum. They all have one thing in common-homage to the elements truly representative of the other side. The Devil and his works have long assumed many forms. Until recently, to Catholics, Protestants were devils. To Protes- tants, Catholics were devils. -

2021 Transpacific Yacht Race Event Program

TRANSPACTHE FIFTY-FIRST RACE FROM LOS ANGELES 2021 TO HONOLULU 2 0 21 JULY 13-30, 2021 Comanche: © Sharon Green / Ultimate Sailing COMANCHE Taxi Dancer: © Ronnie Simpson / Ultimate Sailing • Hamachi: © Team Hamachi HAMACHI 2019 FIRST TO FINISH Official race guide - $5.00 2019 OVERALL CORRECTED TIME WINNER P: 808.845.6465 [email protected] F: 808.841.6610 OFFICIAL HANDBOOK OF THE 51ST TRANSPACIFIC YACHT RACE The Transpac 2021 Official Race Handbook is published for the Honolulu Committee of the Transpacific Yacht Club by Roth Communications, 2040 Alewa Drive, Honolulu, HI 96817 USA (808) 595-4124 [email protected] Publisher .............................................Michael J. Roth Roth Communications Editor .............................................. Ray Pendleton, Kim Ickler Contributing Writers .................... Dobbs Davis, Stan Honey, Ray Pendleton Contributing Photographers ...... Sharon Green/ultimatesailingcom, Ronnie Simpson/ultimatesailing.com, Todd Rasmussen, Betsy Crowfoot Senescu/ultimatesailing.com, Walter Cooper/ ultimatesailing.com, Lauren Easley - Leialoha Creative, Joyce Riley, Geri Conser, Emma Deardorff, Rachel Rosales, Phil Uhl, David Livingston, Pam Davis, Brian Farr Designer ........................................ Leslie Johnson Design On the Cover: CONTENTS Taxi Dancer R/P 70 Yabsley/Compton 2019 1st Div. 2 Sleds ET: 8:06:43:22 CT: 08:23:09:26 Schedule of Events . 3 Photo: Ronnie Simpson / ultimatesailing.com Welcome from the Governor of Hawaii . 8 Inset left: Welcome from the Mayor of Honolulu . 9 Comanche Verdier/VPLP 100 Jim Cooney & Samantha Grant Welcome from the Mayor of Long Beach . 9 2019 Barndoor Winner - First to Finish Overall: ET: 5:11:14:05 Welcome from the Transpacific Yacht Club Commodore . 10 Photo: Sharon Green / ultimatesailingcom Welcome from the Honolulu Committee Chair . 10 Inset right: Welcome from the Sponsoring Yacht Clubs . -

Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone Land Use in Northern Nevada: a Class I Ethnographic/Ethnohistoric Overview

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Bureau of Land Management NEVADA NORTHERN PAIUTE AND WESTERN SHOSHONE LAND USE IN NORTHERN NEVADA: A CLASS I ETHNOGRAPHIC/ETHNOHISTORIC OVERVIEW Ginny Bengston CULTURAL RESOURCE SERIES NO. 12 2003 SWCA ENVIROHMENTAL CON..·S:.. .U LTt;NTS . iitew.a,e.El t:ti.r B'i!lt e.a:b ~f l-amd :Nf'arat:1.iern'.~nt N~:¥G~GI Sl$i~-'®'ffl'c~. P,rceP,GJ r.ei l l§y. SWGA.,,En:v,ir.e.m"me'Y-tfol I €on's.wlf.arats NORTHERN PAIUTE AND WESTERN SHOSHONE LAND USE IN NORTHERN NEVADA: A CLASS I ETHNOGRAPHIC/ETHNOHISTORIC OVERVIEW Submitted to BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Nevada State Office 1340 Financial Boulevard Reno, Nevada 89520-0008 Submitted by SWCA, INC. Environmental Consultants 5370 Kietzke Lane, Suite 205 Reno, Nevada 89511 (775) 826-1700 Prepared by Ginny Bengston SWCA Cultural Resources Report No. 02-551 December 16, 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................v List of Tables .................................................................v List of Appendixes ............................................................ vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................1 CHAPTER 2. ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW .....................................4 Northern Paiute ............................................................4 Habitation Patterns .......................................................8 Subsistence .............................................................9 Burial Practices ........................................................11 -

Craters of the Pluto-Charon System

Icarus 287 (2017) 187–206 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus Craters of the Pluto-Charon system ∗ Stuart J. Robbins a, , Kelsi N. Singer a, Veronica J. Bray b, Paul Schenk c, Tod R. Lauer d, Harold A. Weaver e, Kirby Runyon e, William B. McKinnon f, Ross A. Beyer g,h, Simon Porter a, Oliver L. White h, Jason D. Hofgartner i, Amanda M. Zangari a, Jeffrey M. Moore h, Leslie A. Young a, John R. Spencer a, Richard P. Binzel j, Marc W. Buie a, Bonnie J. Buratti i, Andrew F. Cheng e, William M. Grundy k, Ivan R. Linscott l, Harold J. Reitsema m, Dennis C. Reuter n, Mark R. Showalter g,h, G. Len Tyler l, Catherine B. Olkin a, Kimberly S. Ennico h, S. Alan Stern a, the New Horizons LORRI, MVIC Instrument Teams a Southwest Research Institute, 1050 Walnut St., Suite 300, Boulder, CO 80302, United States b Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States c Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston, TX, United States d National Optical Astronomy Observatory, Tucson, AZ 85726, United States e The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States f Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, United States g SETI Institute, 189 Bernardo Avenue, Suite 100, Mountain View CA 94043, United States h NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 84043, United States i NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, United States j Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States k Lowell Observatory, Flagstaff, AZ, United States l Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States m Ball Aerospace, Boulder, CO, United States n NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD, United States a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: NASA’s New Horizons flyby mission of the Pluto-Charon binary system and its four moons provided hu- Received 3 March 2016 manity with its first spacecraft-based look at a large Kuiper Belt Object beyond Triton. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 113 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 113 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 160 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, JANUARY 30, 2014 No. 18 House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Friday, January 31, 2014, at 3 p.m. Senate THURSDAY, JANUARY 30, 2014 The Senate met at 10 a.m. and was to the Senate from the President pro ahead, and I think it is safe to say that called to order by the Honorable CHRIS- tempore (Mr. LEAHY). despite the hype, there was not a whole TOPHER MURPHY, a Senator from the The legislative clerk read the fol- lot in this year’s State of the Union State of Connecticut. lowing letter: that would do much to alleviate the U.S. SENATE, concerns and anxieties of most Ameri- PRAYER PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, cans. There was not anything in there The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- Washington, DC, January 30, 2014. that would really address the kind of fered the following prayer: To the Senate: dramatic wage stagnation we have seen Let us pray. Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, over the past several years among the Eternal Spirit, we don’t know all of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby middle class or the increasingly dif- appoint the Honorable CHRISTOPHER MURPHY, that this day holds, but we know that a Senator from the State of Connecticut, to ficult situation people find themselves You hold this day in Your sovereign perform the duties of the Chair. -

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time and Text Ashley D. Polasek Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY awarded by De Montfort University December 2014 Faculty of Art, Design, and Humanities De Montfort University Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 Theorising Character and Modern Mythology ............................................................ 1 ‘The Scarlet Thread’: Unraveling a Tangled Character ...........................................................1 ‘You Know My Methods’: Focus and Justification ..................................................................24 ‘Good Old Index’: A Review of Relevant Scholarship .............................................................29 ‘Such Individuals Exist Outside of Stories’: Constructing Modern Mythology .......................45 CHAPTER ONE: MECHANISMS OF EVOLUTION ............................................. 62 Performing Inheritance, Environment, and Mutation .............................................. 62 Introduction..............................................................................................................................62 -

100M Dash (5A Girls) All Times Are FAT, Except

100m Dash (5A Girls) All times are FAT, except 2 0 2 1 R A N K I N G S A L L - T I M E T O P - 1 0 P E R F O R M A N C E S 1 12 Nerissa Thompson 12.35 North Salem 1 Margaret Johnson-Bailes 11.30a Churchill 1968 2 12 Emily Stefan 12.37 West Albany 2 Kellie Schueler 11.74a Summit 2009 3 9 Kensey Gault 12.45 Ridgeview 3 Jestena Mattson 11.86a Hood River Valley 2015 4 12 Cyan Kelso-Reynolds 12.45 Springfield 4 LeReina Woods 11.90a Corvallis 1989 5 10 Madelynn Fuentes 12.78 Crook County 5 Nyema Sims 11.95a Jefferson 2006 6 10 Jordan Koskondy 12.82 North Salem 6 Freda Walker 12.04c Jefferson 1978 7 11 Sydney Soskis 12.85 Corvallis 7 Maya Hopwood 12.05a Bend 2018 8 12 Savannah Moore 12.89 St Helens 8 Lanette Byrd 12.14c Jefferson 1984 9 11 Makenna Maldonado 13.03 Eagle Point Julie Hardin 12.14c Churchill 1983 10 10 Breanna Raven 13.04 Thurston Denise Carter 12.14c Corvallis 1979 11 9 Alice Davidson 13.05 Scappoose Nancy Sim 12.14c Corvallis 1979 12 12 Jada Foster 13.05 Crescent Valley Lorin Barnes 12.14c Marshall 1978 13 11 Tori Houg 13.06 Willamette Wind-Aided 14 9 Jasmine McIntosh 13.08 La Salle Prep Kellie Schueler 11.68aw Summit 2009 15 12 Emily Adams 13.09 The Dalles Maya Hopwood 12.03aw Bend 2016 16 9 Alyse Fountain 13.12 Lebanon 17 11 Monica Kloess 13.14 West Albany C L A S S R E C O R D S 18 12 Molly Jenne 13.14 La Salle Prep 9th Kellie Schueler 12.12a Summit 2007 19 9 Ava Marshall 13.16 South Albany 10th Kellie Schueler 12.01a Summit 2008 20 11 Mariana Lomonaco 13.19 Crescent Valley 11th Margaret Johnson-Bailes 11.30a Churchill 1968 -

March 21–25, 2016

FORTY-SEVENTH LUNAR AND PLANETARY SCIENCE CONFERENCE PROGRAM OF TECHNICAL SESSIONS MARCH 21–25, 2016 The Woodlands Waterway Marriott Hotel and Convention Center The Woodlands, Texas INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT Universities Space Research Association Lunar and Planetary Institute National Aeronautics and Space Administration CONFERENCE CO-CHAIRS Stephen Mackwell, Lunar and Planetary Institute Eileen Stansbery, NASA Johnson Space Center PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS David Draper, NASA Johnson Space Center Walter Kiefer, Lunar and Planetary Institute PROGRAM COMMITTEE P. Doug Archer, NASA Johnson Space Center Nicolas LeCorvec, Lunar and Planetary Institute Katherine Bermingham, University of Maryland Yo Matsubara, Smithsonian Institute Janice Bishop, SETI and NASA Ames Research Center Francis McCubbin, NASA Johnson Space Center Jeremy Boyce, University of California, Los Angeles Andrew Needham, Carnegie Institution of Washington Lisa Danielson, NASA Johnson Space Center Lan-Anh Nguyen, NASA Johnson Space Center Deepak Dhingra, University of Idaho Paul Niles, NASA Johnson Space Center Stephen Elardo, Carnegie Institution of Washington Dorothy Oehler, NASA Johnson Space Center Marc Fries, NASA Johnson Space Center D. Alex Patthoff, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Cyrena Goodrich, Lunar and Planetary Institute Elizabeth Rampe, Aerodyne Industries, Jacobs JETS at John Gruener, NASA Johnson Space Center NASA Johnson Space Center Justin Hagerty, U.S. Geological Survey Carol Raymond, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Lindsay Hays, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Paul Schenk, -

Picturing France

Picturing France Classroom Guide VISUAL ARTS PHOTOGRAPHY ORIENTATION ART APPRECIATION STUDIO Traveling around France SOCIAL STUDIES Seeing Time and Pl ace Introduction to Color CULTURE / HISTORY PARIS GEOGRAPHY PaintingStyles GOVERNMENT / CIVICS Paris by Night Private Inve stigation LITERATURELANGUAGE / CRITICISM ARTS Casual and Formal Composition Modernizing Paris SPEAKING / WRITING Department Stores FRENCH LANGUAGE Haute Couture FONTAINEBLEAU Focus and Mo vement Painters, Politics, an d Parks MUSIC / DANCENATURAL / DRAMA SCIENCE I y Fontainebleau MATH Into the Forest ATreebyAnyOther Nam e Photograph or Painting, M. Pa scal? ÎLE-DE-FRANCE A Fore st Outing Think L ike a Salon Juror Form Your Own Ava nt-Garde The Flo ating Studio AUVERGNE/ On the River FRANCHE-COMTÉ Stream of Con sciousness Cheese! Mountains of Fra nce Volcanoes in France? NORMANDY “I Cannot Pain tan Angel” Writing en Plein Air Culture Clash Do-It-Yourself Pointillist Painting BRITTANY Comparing Two Studie s Wish You W ere Here Synthétisme Creating a Moo d Celtic Culture PROVENCE Dressing the Part Regional Still Life Color and Emo tion Expressive Marks Color Collectio n Japanese Prin ts Legend o f the Château Noir The Mistral REVIEW Winds Worldwide Poster Puzzle Travelby Clue Picturing France Classroom Guide NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON page ii This Classroom Guide is a component of the Picturing France teaching packet. © 2008 Board of Trustees of the National Gallery of Art, Washington Prepared by the Division of Education, with contributions by Robyn Asleson, Elsa Bénard, Carla Brenner, Sarah Diallo, Rachel Goldberg, Leo Kasun, Amy Lewis, Donna Mann, Marjorie McMahon, Lisa Meyerowitz, Barbara Moore, Rachel Richards, Jennifer Riddell, and Paige Simpson. -

Ernest Guiraud: a Biography and Catalogue of Works

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1990 Ernest Guiraud: A Biography and Catalogue of Works. Daniel O. Weilbaecher Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Weilbaecher, Daniel O., "Ernest Guiraud: A Biography and Catalogue of Works." (1990). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4959. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4959 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps.