Development of a Bakery Snack for Export from New Zealand to Malaysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brentwood Social House Catering Menu Savory Items

BSH Catering Pricing (as of 11/18/20) Brentwood Social House Catering Menu As of November 18, 2020 (COVID Catering) Prices and item availabilty subject to change depending on ingredient availability during COVID-19 circumstances. We require at least 24 hours in advance notice for custom orders. Please email [email protected] to place your order. A 10% service charge is added to all catering orders. For pick up only. Savory Items Product Name Description Catering Price Notes Chicken Pie All-natural white meat chicken in a fennel-spiced cream $7.85 Baked or frozen (Indivual hand pie) sauce Vegan Curry Pie Vegan pie crust filled with roasted cauliflower and chickpeas Vegan $7.25 (Indivual hand pie) in an Indian-spiced curry [Vegan] Baked or frozen Pork and beef sausage from Slovacek Sausage in Snook, Texas Sausage Roll $5.50 Baked or frozen Texas wrapped in Belgian puff pastry Min order: 12 Mini Texas Sausage Roll Smaller version of our Texas sausage roll $2.75 Baked or frozen Fresh spinach, feta, and egg baked in a buttery crust, Spinach Feta Quiche $6.00 Vegetarian topped with tomatoes. Individual serving. [Vegetarian] Roasted potato, onion, tomato, and eggs baked in a buttery Roasted Potato Quiche $6.00 Vegetarian crust. Individual serving. [Vegetarian] Antonelli’s Cheddar cheese wrapped inBelgian puff pastry Vegetarian Cheddar Cheese Pasty $5.50 [Vegetarian] Baked or frozen Buttery Croissant Authentic croissant importedfrom France $3.00 Not available due to supply issue Sliced ham and cheddar cheese with a mustard-mayo Ham & Cheddar Croissant $6.50 Not available due to supply issue spread in a French croissant Three soft pretzel sticks served with a trio of dipping sauces: Soft Pretzel Sticks (3 sticks) house-made mustard, house-made raspberry honey $5.00 mustard, and spicy brown mustard. -

Bakery Price List

BAKERY GOODS ROLLS PRICE SLICED BREAD PRICE MORNING ROLL £0.31 HOMESTYLE WHITE 800G £2.00 WHEATEN ROLL £0.36 RICH FRUIT LOAF £2.45 BARM £0.35 MULTISEED 800G £2.38 BURGER ROLL £0.35 COUNTRY COARSE 400G £1.90 GRANARY ROLL £0.36 CRUSTY 400G £1.90 ROUGH W/MEAL ROLL £0.35 GLENCRUST 400G £2.00 CRACKED WHEAT ROLL £0.35 WHEATMEAL 400G £1.76 TRADITIONAL ROLL £0.32 BERRYMEAL 400G £2.00 CHEESY BAP £0.42 CRUSTY 800G £2.80 POPPYSEED FINGER £0.35 RUSTIC 800G £2.95 WHITE DINNER ROLL £0.26 RUSTIC 400G £2.00 BROWN DINNER ROLL £0.26 HERB & ONION 400G £2.05 FYNE HERB & ONION DINNER ROLL £0.28 BROWN SANDWICH LOAF 800G £2.00 WHITE SUB £0.45 SOFTIE £0.35 NEW YORK HOT DOG ROLL £0.40 TEABREAD BRIOCHE ROLL £0.62 OATIE SUB £0.45 PLAIN COOKIE £0.40 HERB & ONION SUB £0.45 FARM SCONE £0.78 LARGE POPPYSEED SUB £0.45 COTTAGE SCONE £0.50 SULTANA SCONE £0.50 BREAD POTATO SCONE £0.33 CRUMPET £0.50 CRUSTY 400G £1.90 HOT X BUN £0.42 GLENCRUST 400G £2.00 PANCAKE £0.48 BERRYMEAL 400G £2.00 CROISSANT £0.56 BAGUETTE £2.00 WHEATMEAL 400G £1.76 COUNTRY COARSE 400G £1.90 HERB & ONION 400G £2.05 RICH FRUIT LOAF £2.45 DO-NUTS RUSTIC 800G £2.95 CRUSTY 800G £2.80 SUGAR RING DO-NUT £0.54 BROICHE LOAF 400G £1.90 ICED DO-NUT £0.70 RUSTIC 400G £2.00 JAM BALL DO-NUT £0.70 PASTRIES PRICE CONFECTIONERY SMALL PRICE CAKES APPLE TART S/CRUST £2.65 CHOCOLATE & MARZIPAN £0.86 LOG RHUBARB TART S/CRUST £2.65 FRENCH CAKE £0.80 DANISH PASTRY £0.94 TOFFEE SLICE £0.82 APPLE TURNOVER £1.06 ICED GINGER SLICE £0.80 CHELSEA BUN £0.94 FERN CAKE £0.72 APPLE & CUSTARD DANISH £1.06 PINEAPPLE PEAK £0.78 RASPBERRY -

Official Great Aussie Pie Competition - Sydney 9Th to 12Th September 2019 2019 TOP 3 Results (Gold, Silver & Bronze Medallists Pages 3-29)

Official Great Aussie Pie Competition - Sydney 9th to 12th September 2019 2019 TOP 3 Results (Gold, Silver & Bronze Medallists pages 3-29) Plain Meat Pie - Top 5! 1st - Pinjarra Bakery, Pinjarra, WA (Mince) 2nd - Rolling Pin Pies & Cakes, Ocean Grove, VIC (Chunky/Combo) 3rd - Mount Barker Country Bakery, Mount Barker, WA (Mince/Chunky Combo) 4th - Oven Crisp Bakery, Riverton, WA (Mince) 5th - Baked Provisions, Wangara, WA (Mince) Overall Gourmet Pie 1st - Old Fernvale Bakery, Fernvale QLD (Creamy Seafood) 2nd - Mountain High Pies, Wentworth Falls, NSW (Peri Peri Chicken & Mango Salsa) 3rd - Parker Pies, Rutherglen, VIC (Smoked Beef & Truffle Pie) Plain Sausage Roll 1st - Tatura Hot Bread, Tatura, VIC 2nd - Mayfield Patisseries and Chocolates, Montville, QLD 3rd - Red Poppy Bakery, Hughesdale, VIC Gourmet Sausage Roll 1st - Molly Dene Bakehouse, Bentleigh, VIC (Lasagne Roll) 2nd - Mayfield Patisseries and Chocolates, Montville, QLD (Mediterranean Lamb Roll) 3rd - Mayfield Patisseries and Chocolates, Montville, QLD (Turkey) Poultry Pie 1st - Mountain High Pies, Wentworth Falls, NSW (Peri Peri Chicken and Mango Salsa) 2nd - Uppercrust Pies, Collaroy, NSW (Butter Chicken) 3rd - Orange Sport Bakery, Glenelg, SA (French Honey Chicken) Red Meat Pie 1st - Parker Pies, Rutherglen, VIC (Smoked Beef & Truffle Pie) 2nd - Mount Barker Country Bakery, Mount Barker, WA (Lamb Braised in Redwine) 3rd - Country Cobb Bakery, Kynenton, VIC (Lamb Ragu) Brekkie Pie 1st - Mountain High Pies NSW (Big Brekkie) 2nd - Bels Gordon Street bakery, Port Macquarie, NSW -

Catering Menu

EXPLORE OUR FLAVORS COURTYARD BY MARRIOTT CALGARY SOUTH RESIDENCE INN BY MARRIOTT CALGARY SOUTH ® COURTYARD3750 MarketBALTIMORE Street SE, 3710 Market Street SE, DOWNTOWN/INNER HARBOR 1000Calgary, Aliceanna AB,Street T3M 1M4| Baltimore, MD 21202 Calgary, AB, T3M 1M4 443.923.4000587.349.7599| Marriott.com/MARSHA 587.349.8633 BREAKFAST 17 CONTINENTAL ONE 25 CLASSIC CANADIAN BREAKFAST Selection of fresh baked pastries | Butter Croissants, Freshly Baked Butter Croissant, Assorted Miniature Mini Muffins, Danishes with fruit preserves & butter Danishes & Muffins, fruit preserves & butter Individual Non-Fat Fruit Yogurts Fresh Cut Fruit & Berries Hardboiled Eggs Individual 0% Fruit Yogurts Fresh Cut Fruit & Berries Farm-Fresh Hash Brown Potatoes Chilled Orange, Apple & Cranberry Juice Free Range Scrambled Eggs Fresh Brewed Starbucks Regular & Decaffeinated Chilled Orange, Apple & Cranberry Juice Coffee & Assorted Tazo Teas Freshly Brewed Starbucks Regular & Decaffeinated Coffee & Assorted Tazo Tea 22 CONTINENTAL TWO Choice of Two Options: Fresh Baked Saskatoon Berry Scones with fruit • Spolumbo Pork Maple Sausage preserves & butter • Spolumbo Cranberry Turkey Sausage Hot Steel Cut Oatmeal • Spolumbo Chicken Chorizo Sausage Build Your Own Breakfast Parfait | Low Fat Plain Greek Yogurt, low-fat granola cereal, dried cranberries, • Crisp Applewood Smoked Bacon raisins, walnuts, toasted almonds, honey, chocolate • Honey Maple Smoked Ham chips, mango puree, caramel & chocolate syrup Seasonal Fresh Fruit & Berries 2% & Skim Milk, Orange, Apple & Cranberry -

Cookbook Committee Special Thanks to Jenn Springer for the Wonderful Idea and Countless Hours Collecting and Typing Recipes ~ As Well As Her Committee

2009 | www.frogtummy.com . Cookbook Committee Special thanks to Jenn Springer for the wonderful idea and countless hours collecting and typing recipes ~ as well as her committee. Jenn Springer Gennessa Robbins Relief Society Presidency 2009- PRESENT Robin Rudd Melanie Butler Kathy Robbins Staci Potter Relief Society Presidency 2006- 2009 Vicki Christensen Helen Schenck DeAnn Hoggan Krista Hansen Appetizers ..................................................... 16 Texas Caviar ................................................................................................... 17 Sun-dried Tomatoes (well, sort of) ............................................................... 17 Open-Face Crab Ciabatta .......................................................................... 18 Cheese Spread .............................................................................................. 18 Cheese Fondue ............................................................................................. 18 Stuffed Mushrooms ........................................................................................ 19 Stuffed Mushrooms ........................................................................................ 19 Fantastic Ranch Cheese Balls ..................................................................... 20 Tomato & Cream Cheese Appetizer .......................................................... 20 Ham Cheese Ball ........................................................................................... 20 Lettuce Wraps ............................................................................................... -

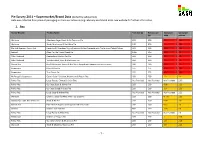

Full Supermarket Data

Pie Survey 2011 – Supermarket/Brand Data (Sorted by salt/portion) Data was collected from product packaging in store and online during February and March 2011. See website for further information. 1. Pies Brand/ Retailer Product Name Pack Size (g) Portion size Salt (g) per Salt (g) per (g) 100g portion Waitrose Aberdeen Angus Steak & Ale Top crust Pie 600 300 0.9 2.69 Waitrose Steak, Mushroom & Red Wine Pie 540 270 1 2.69 Marks & Spencer Gastro Pub (main for 1) Aberdeen Angus Steak and Stilton Pie made with Tuxford and Tebutt Stilton 260 260 1.03 2.68 Iceland (Meal for the Family) Steak Pie 1400 350 0.8 2.6 Alfie Chadwick Cumberland Chicken Pot Pie 260 260 1.0 2.5 Alfie Chadwick Yorkshire Beef, Beer & Mushroom Pie 260 260 1.0 2.5 Dorset Pies Beef, Mushroom, Bacon & Red Wine topped with caramelised onion scone 280 280 0.9 2.5 Pieminister Moo & Blue Pie 275 275 0.9 2.43 Pieminister Thai Chook Pie 275 275 0.9 2.43 McDougall's Uppercrust Gastro Style 2 Chicken, Mushroom & Bacon Pies 400 200 1.2 2.4 Pukka Pies Large Potato, Cheese & Onion Pies Not Provided Not Provided Not Provided 2.35 Pukka Pies Our Best Steak & Kidney Pie 200 200 0.98 2.33 Pukka Pies Our Best Baked All Steak Pie 200 200 1.0 2.33 Pukka Pies Large Steak & Kidney Pies Not Provided Not Provided Not Provided 2.33 Waitrose Chicken, Bacon & White Wine Top crust Pie 600 300 0.775 2.33 Sainsbury's Taste The Difference Steak & Ale Pie 250 250 0.93 2.31 Dorset Pies Ham Hock & Apple Cider topped with herb scone 280 280 0.8 2.3 Glenfell Chicken and Ham Pie 680 170 1.25 2.3 Pukka Pies -

Summer 2020 Newsletter Merry Christmas a Message from the CEO

Volume 28 Issue 06 Emergency on call ph. 0448 472 007 Summer 2020 Newsletter Merry Christmas A message from the CEO It is hard to believe it is Christmas time Headway has recently completed a new already. It has certainly been a year of firsts strategic plan for 2020 to 2023 and you can for all at Headway. find this on our website on our ‘About Us’ This year has been very challenging for page. all and I would like to pass on my thanks I am also proud to say that due to continued to everyone involved in Headway for growth and demand for our services, our continuing to deliver high-quality services Newborough office is on the move. You can during some very difficult times. find them at 219 Princess Drive, Morwell As we approach Christmas, I wanted to after December 21. wrap up the year with a big thanks to those I wish everyone a very special Christmas. I who continue to provide us with inspirational hope you get time to relax, spend time with stories on our Facebook page. Keep them family and friends and reflect on the year coming, they are fantastic. that was. This year we welcomed many new faces to our team and made many changes and Jenelle Henry continued to build on our strengths. Chief Executive Officer The hard work of Headway personnel came to the ultimate test on 7 and 8 December as we undertook our first audit under the NDIS. Inside this newsletter I am proud to say Headway came away with no major or minor non-conformances. -

Morgans Menu

MORGANS MENU ALL DAY BREAKFAST RANGE SANDWICHES MEALS Regular Bacon or Sausage Bun Buy a Sandwich or a Salad Box Mince & Onion Pie & Peas £2.65 with a Hot Drink (before 11am) £2.25 and a 500ml Bottle of Pop Steak Pie & Peas £2.85 Deep Filled Mince Pie & Peas £2.85 Regular Bacon Bun £1.89 and get a FREE Sausage Roll or Cookie Chicken & Gravy Pie & Peas £2.85 Regular Sausage Bun £1.89 or Packet of Crisps (Offer Excludes Quavers) Chicken Curry Pie & Peas £2.85 Sausage Roll & Beans £1.70 Mix ‘‘n’’ Match 2 for £2..99 (regular size) Freshly Made Sandwich £2.65 each Quiche, Salad & Coleslaw £2.55 2 Regular Bacon or Sausage Buns Choose from:- Quiche & Beans £2.55 With Any 2 Hot Drinks £4.70 Pasty & Beans £2.35 Chicken Cheese Savoury Large Bacon Bun £2.45 Coronation Chicken Ham Add a Hot Drink for 80p Large Sausage Bun £2.45 Garlic Chicken Cheese Large Bacon & Sausage Bun £2.85 SAVOURIES Chicken Tikka Mayo Egg Mayo Breakfast Bun £3.25 Chicken Mayo Tuna Mayo (Bacon, Sausage, Egg, Beans & Mushrooms) Corned Beef Pasty £1.35 BBQ Chicken Seafood Mayo Cheese & Onion Pasty £1.35 Add a Hot Drink for 80p Chicken & Bacon Mayo Mince & Potato Pasty £1.35 Served on a Large White or Brown Bomb Chicken Curry Pasty £1.35 Kid’s Bacon Bun 85p Chicken & Stuffing Pasty £1.35 with Salad of your choice JACKET POTATOES Get a FREE Drink and a FREE Sandwich when Mix ‘‘n’’ Match Any 2 Pasties for £2..00 Plain £1.70 you collect stamps with a Loyalty Card. -

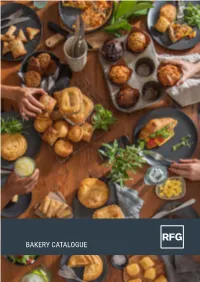

Bakery Catalogue Product Icon Key

BAKERY CATALOGUE PRODUCT ICON KEY WEIGHT THAW OVEN BAKE FROZEN FRIDGE SHELF AMBIENT TIME TEMPERATURE oC TIME SHELF LIFE LIFE UNOPENED SHELF LIFE CONTENTS MAPGIE BAKERY Pastry 02 Topped & Filled Muffins 03 Muffin Tubesets ™ 04 | 05 Croissants & Scrolls 07 Pizza 09 Dry Mixes 09 MAGPIE PIES Classic Oval Foils 11 Pasties 11 Puff Pies 12 Slices 13 Burger Pies 13 Sausage Rolls 15 Mini Pies 15 Puffs & Speciality 15 MAGPIE RETAIL CABINET Individually wrapped Jumbo Muffins 17 Individually wrapped Small Muffins 17 6 pack Muffins 19 Frozen Retail Cabinet 21 MA BAKER PIES Premier Pies 23 Regular Pies 24 Sausage Rolls 25 Individually wrapped Pre-baked Pies 26 MA BAKER SNACKING Samoosas 29 All our products are Halaal certified and produced in Halaal certified facilities. PASTRY 1 KG PUFF PASTRY ROLL 2 KG PUFF PASTRY ROLL 6 KG PUFF PASTRY SHEETS (20 x 300 g) BARCODE: 6005118000625 BARCODE: 6005118001950 BARCODE: 6005118000632 PRODUCT CODE: 70110944 PRODUCT CODE: PUFF PRODUCT CODE: 70110951 1 kg 120-180 mins 200oC 20-25 mins 12 mnths 2 kg 120-180 mins 200oC 20-25 mins 12 mnths 6 kg 120-180 mins 200oC 20-25 mins 12 mnths 02 TOPPED & FILLED MUFFINS CARAMEL FUDGE MUFFIN FILLED CHOC CHOC CHIP MUFFIN FILLED WITH WITH CARAMEL & TOPPED WITH CHOCOLATE GANACHE & TOPPED WITH CARROT MUFFIN FILLED WITH CREAM CHOCOLATE CHUNKS CHOCOLATE CHUNKS CHEESE ICING & TOPPED WITH WALNUTS BARCODE: 6004642004062 BARCODE: 6004642004079 BARCODE: 6005118001660 PRODUCT CODE: 70110851 PRODUCT CODE: 70110852 PRODUCT CODE: 70110853 145 g 90 mins 6 mnths 4 days 140 g 90 mins 6 mnths 4 days 140 g 90 mins 6 mnths 4 days Muffins, croissants, cinnamon scrolls and more, RFG has a range of tried and tested formats and flavours to help you satisfy your consumer’s sweet tooth with very little effort from your baking team. -

Vegetarian Meat Substitutes Products Available in Supermarkets on the Island of Ireland and Consumer Behaviours and Perceptions

Vegetarian meat substitutes Products available in supermarkets on the island of Ireland and consumer behaviours and perceptions Vegetarian meat substitutes Vegetarian meat substitutes ISBN: 978-1-905767-99-1 Publication date: March 2021 1 Vegetarian meat substitutes Foreword Foods such as meat, poultry, fish, eggs, beans, peas, lentils and nuts play a very important role in the diet by providing protein. There has been a growth in the market of vegetarian, plant-based meat substitutes in recent years. safefood undertook a survey of these products currently available in retail outlets on the island of Ireland. This snapshot survey provides detail on the nutritional profile of the products surveyed and compares them with their meat equivalents. The report also provides data on consumer perceptions of these products. i Vegetarian meat substitutes Executive summary Aims To provide an overview of the different types and the nutritional content of vegetarian, plant- based meat substitutes available online from a range of supermarkets on the island of Ireland Investigate consumer perceptions of the nutritional content of vegetarian, plant-based meat substitutes, their reported purchase, motivations and consumption of these products Methods The report presents findings from an online audit of ready-to-eat/cook vegetarian main meal vegetarian, plant-based meat substitutes available in supermarkets on the island of Ireland between 28 April and 26 May 2020. Consumers’ behaviours and motivations for purchasing vegetarian, plant- based meat substitutes were determined via the safefood safetrak survey of 802 consumers (500 ROI and 302 NI) between mid-November 2020 and mid-December 2020. Key findings What type of vegetarian, plant-based meat substitutes are available? The audit identified 354 products in : o Meat-style meat-substitute burgers (n=28) o Bean/vegetable-style meat-substitute burgers (n=36) o Meat-substitute steaks, mince, meatballs and Bolognese (n=31) o Chicken substitutes e.g. -

Whitsunday Foodservice - Wholesale Price List

WHITSUNDAY FOODSERVICE - WHOLESALE PRICE LIST TABLE OF CONTENTS ****M CreatedCONTENTS by SA update 5 ****O OTHER CHARGES 5 ANTI Antipasto 5 ASIAN Asian Ingredients 6 ASIAS Asian Sauces 8 BAIT Bait 9 BAKER Bakery 9 BAKRD Bakery Dry 10 BEV Beverage 12 BEVCA Beverage Carbonated 12 BISC Biscuits 13 BISCS Biscuits Savoury 14 BISFR Biscuits RTB Frozen 14 BRFRE Bread 15 BRFRO Breads Frozen 16 BRFRS Breads Frz Specialty 17 BRFRT Bread Frzn Tortillas 17 BUTTE Butter Margarine 17 CAKES Cakes 17 CAKFI Cakes Fresh - Indv 17 CAKFW Cakes Fresh - Whole 18 CAKMU Cakes - Muffins Frz 18 CAKPC Cakes - Portions Frz 18 CAKSC Cakes - Cookies Frz 19 CAKTR Cakes - Trays Frz 19 CAKWH Cakes - Whole Frz 19 CANFR Canned Fruit 20 CANTO Canned Tomatoes 21 CER Cereal - Foodservice 21 CERPC Cereal - Portions 21 CHBLU Cheese Blue 22 CHCRE Cream Cheese 22 CHEWR Cheese Washed Rind 22 CHFOO Cheddar Foodservice 22 CHFRE Cheese 22 CHMOZ Mozzarella/Pizza Ch 23 CHPAR Cheese Parmesan 23 CHPOR Cheese Portion 23 CHSPE Cheddar Specialty 23 CHSWI Swiss Cheese 23 CHWMO Cheese White Mould 24 CHZIP Chips 24 CINGR Canned Ingredients 24 CIVEG Canned Ingred Vege 25 CKRTC Chickn Heat & Serve 25 CLEAN Cleaning Products 26 COFCO Coffee/Cocktail Syrp 26 COFFE Coffee Miscellaneous 27 COFFL Coffee Lavazza 28 COFFV Coffee Vittoria 28 CONDI Condiments 28 CONF Confectionary Bars 29 CONFM Confectionary Misc 29 CONV Potato Chips & Nuts 30 COOKC Cooking Chocolate 30 CRCHE Cream Cheese 31 CREAM Cream 31 CUSTD Custard 31 DIPS Dips 31 EGGS Eggs 31 FF/FR Finger Food Frozen 32 FFCHI Frozen Chicken 33 -

Company Name Award Entry Pie Class* A. F. Huddleston's Butchers Ltd Gold 4458 Pork Pie 2 A

Company Name Award Entry Pie Class* A. F. Huddleston's Butchers Ltd Gold 4458 Pork Pie 2 A. F. Huddleston's Butchers Ltd Silver 4459 Lamb Hot Pot Pie 11 A. F. Huddleston's Butchers Ltd Silver 4456 Steak Pie 7 A.E Ross & son T/A Lawns Farm Shop Silver 4831 Lamb and Mint Pie 11 A.E Ross & son T/A Lawns Farm Shop Bronze 4832 Pheasant & Tarragon Pie 15 A.E Ross & son T/A Lawns Farm Shop Bronze 4830 Chicken And Leek Pie 13 Addington Pies Gold 4898 In the Net Pie 17 Addington Pies Silver 4436 Addington Steak and Kidney Pie 6 Addington Pies Silver 4439 Moroccan Goat Tangine Pie 16 Addington Pies Silver 4438 BBQ Chicken and Ham Pie 21 Addington Pies Bronze 4437 Angus The Bishop and The Old Speckled Hen Pie 20 Addington Pies Bronze 4435 Addington Chicken and Haggis Pie 14 AE.Chambers Ltd Gold 4424 Steak and Gravy Pie 7 AE.Chambers Ltd Silver 4421 Pork Pie 2 AE.Chambers Ltd Bronze 4425 Chamber's Turkey Ham and Cranberry Pie 3 AE.Chambers Ltd Bronze 4422 Charcoal Ploughmans 3 AE.Chambers Ltd Bronze 4423 Bury Pork Pie 3 AE.Chambers Ltd Bronze 4427 Chamber's Steak and Ale Pie 8 Aldi Silver 4652 Aldi Specially Selected Chicken Ham Hock and Leek 14 Aldi Silver 4650 Aldi Plant Menu - Vegan Pasty 19 Andy Saunders Catering Gold 4702 Andy Saunders Catering Steak and Stilton Pie 9 Andy Saunders Catering Silver 4703 The Plough Pie 20 Bakeshack Gold 4582 Bakeshack Pheasant with Goji Berries and Chestnuts in Port Pie 15 Bakeshack Bronze 4155 Bakeshack Chinese Black Peppered Beef with Water Chestnuts Pie 16 Bakeshack Bronze 4584 Bakeshack Chinese Wheat Gluten