Distribution Agreement in Presenting This Thesis Or Dissertation As A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tayinat's Building XVI: the Religious Dimensions and Significance of A

Tayinat’s Building XVI: The Religious Dimensions and Significance of a Tripartite Temple at Neo-Assyrian Kunulua by Douglas Neal Petrovich A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto © Copyright by Douglas Neal Petrovich, 2016 Building XVI at Tell Tayinat: The Religious Dimensions and Significance of a Tripartite Temple at Neo-Assyrian Kunulua Douglas N. Petrovich Doctor of Philosophy Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto 2016 Abstract After the collapse of the Hittite Empire and most of the power structures in the Levant at the end of the Late Bronze Age, new kingdoms and powerful city-states arose to fill the vacuum over the course of the Iron Age. One new player that surfaced on the regional scene was the Kingdom of Palistin, which was centered at Kunulua, the ancient capital that has been identified positively with the site of Tell Tayinat in the Amuq Valley. The archaeological and epigraphical evidence that has surfaced in recent years has revealed that Palistin was a formidable kingdom, with numerous cities and territories having been enveloped within its orb. Kunulua and its kingdom eventually fell prey to the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which decimated the capital in 738 BC under Tiglath-pileser III. After Kunulua was rebuilt under Neo- Assyrian control, the city served as a provincial capital under Neo-Assyrian administration. Excavations of the 1930s uncovered a palatial district atop the tell, including a temple (Building II) that was adjacent to the main bit hilani palace of the king (Building I). -

Return to the Temple of Elemental Evil ERRATA and FAQ

Return to the Temple of Elemental Evil ERRATA AND FAQ A collaborative product of the members of Monte Cook's Return to the Temple of Elemental Evil web forum. Compiled, edited, and formatted by Siobharek. PDF version edited by ZansForCans. Modified: 11 February 2003 The definitive source for this errata and FAQ can be found in the ‘sticky’ threads at the top of the topic list on Monte Cook's Return to the Temple of Elemental Evil web forum. None of these errata or FAQ are official in any way (i.e. Monte or WotC have not said "That's right."), but most have been agreed to be accurate and true to the core rulebooks by many DMs running this adventure. NPC stats corrections are grouped in the appropriate chapter that the NPC appears in. In some cases, there is no ‘fix’ suggested—the errata is simply provided to alert you to a discrepancy. You didn’t think we’d do all the work for you, did you? It may seem like there are quite a lot of errata for this product. There are! Part of the explanation we have heard is that Monte was working on the adventure while D&D 3e was still being finalized. The rest we simply blame on his editors. ;) We welcome further corrections and additions to this list. However, when and if you find something that doesn't seem right, please check in every available rulebook. For instance, adding the right number of feats and stat increases to monsters with classes can be fiendishly hard but check it and double check it as much as you can. -

The-Odyssey-Greek-Translation.Pdf

05_273-611_Homer 2/Aesop 7/10/00 1:25 PM Page 273 HOMER / The Odyssey, Book One 273 THE ODYSSEY Translated by Robert Fitzgerald The ten-year war waged by the Greeks against Troy, culminating in the overthrow of the city, is now itself ten years in the past. Helen, whose flight to Troy with the Trojan prince Paris had prompted the Greek expedition to seek revenge and reclaim her, is now home in Sparta, living harmoniously once more with her husband Meneláos (Menelaus). His brother Agamémnon, commander in chief of the Greek forces, was murdered on his return from the war by his wife and her paramour. Of the Greek chieftains who have survived both the war and the perilous homeward voyage, all have returned except Odysseus, the crafty and astute ruler of Ithaka (Ithaca), an island in the Ionian Sea off western Greece. Since he is presumed dead, suitors from Ithaka and other regions have overrun his house, paying court to his attractive wife Penélopê, endangering the position of his son, Telémakhos (Telemachus), corrupting many of the servants, and literally eating up Odysseus’ estate. Penélopê has stalled for time but is finding it increasingly difficult to deny the suitors’ demands that she marry one of them; Telémakhos, who is just approaching young manhood, is becom- ing actively resentful of the indignities suffered by his household. Many persons and places in the Odyssey are best known to readers by their Latinized names, such as Telemachus. The present translator has used forms (Telémakhos) closer to the Greek spelling and pronunciation. -

To Bible Study the Septuagint - Its History

Concoll()ia Theological Monthly APRIL • 1959 Aids to Bible Study The Septuagint - Its History By FREDERICK W. DANKER "GENTLEMEN, have you a Septuagint?" Ferdinand Hitzig, eminent Biblical critic and Hebraist, used to say to his class. "If not, sell all you have, and buy a Septuagint." Current Biblical studies reflect the accuracy of his judgment. This and the next installment are therefore dedicated to the task of helping the Septuagint come alive for Biblical students who may be neglecting its contributions to the total theological picture, for clergymen who have forgotten its interpretive possibilities, and for all who have just begun to see how new things can be brought out of old. THE LETTER OF ARISTEAS The Letter of Aristeas, written to one Philocrates, presents the oldest, as well as most romantic, account of the origin of the Septuagint.1 According to the letter, Aristeas is a person of con siderable station in the court of Ptolemy Philadelphus (285-247 B. C.). Ptolemy was sympathetic to the Jews. One day he asked his librarian Demetrius (in the presence of Aristeas, of course) about the progress of the royal library. Demetrius assured the king that more than 200,000 volumes had been catalogued and that he soon hoped to have a half million. He pointed out that there was a gap ing lacuna in the legal section and that a copy of the Jewish law would be a welcome addition. But since Hebrew letters were as difficult to read as hieroglyphics, a translation was a desideratum. 1 The letter is printed, together with a detailed introduction, in the Appendix to H. -

Eberron Jumpchain

Eberron Jumpchain By Jim the Hate Fish Welcome to the wonderful world of Eberron! Twelve moons hang in the sky, with a belt of shattered rocks suffusing it. The twelve Dragonmarked houses rule over all aspects of life, each sponsoring a member of the Twelve, wizards dedicated to keeping the peace. Swashbuckling rogues work alongside ingenious craftsmen, wielding swords and shield and automatic crossbows. Robotic soldiers, remnants of the last great war, tread the streets, living the closest they can to normal lives, albeit typically normal lives as mercenaries. Spellslingers craft works of true arcana, ships that travel the sky, trains fuelled by lightning, and stone tablets that can communicate over great distances. You have 1000CP to spend. In addition, you get an Origin, Race, Class and Starting Location for free, as well as being able to set your age and gender as you please. Starting Location You may either roll an eight-sided die, starting at the relevant location, or pay 50CP to choose. The location you start at within each given area is at your discretion. 1: Breland. Breland is one of the five nations of central Khorvaire, lying in the southwest of the continent enjoying one of the largest areas of the nations and territories. Breland is a mix of open farmland, woodland and sprawling metropolis, the most famous of which is Sharn. 2: The Mournland. Once, Cyre shone more brightly than any of its sibling nations in the kingdom of Galifar. The Last War took a toll on the nation and its citizens, until disaster struck. -

French-Egyptian Centre for the Study of the Temples of Karnak

FRENCH-EGYPTIAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF THE TEMPLES OF KARNAK Luxor, 2017 Ministry of Antiquities of Egypt Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique Ministère des Affaires Étrangères et du Développement International FRENCH-EGYPTIAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF THE TEMPLES OF KARNAK ACTIVITY REPORT 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ............................................................................................................................................ 4 1. SCIENTIFIC PROGRAMMES ................................................................................................................ 7 1.1. Power and marks of Power at Karnak ........................................................................................ 7 1.1.1. The Sphinx of Pinudjem ............................................................................................................. 7 1.1.2. The 8th Pylon ............................................................................................................................. 7 1.2. Peripheral areas ............................................................................................................................. 9 1.2.1. The Temple of Ptah ................................................................................................................... 9 1.3. Cults and places of worship .......................................................................................................... 28 1.3.1. The Monuments of Amenhotep I .............................................................................................. -

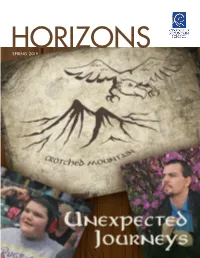

SPRING 2019 Horizons Table of Contents Spring 2019 Written and Photographed By: from the President

HORIZONS SPRING 2019 Horizons Table of Contents Spring 2019 Written and Photographed by: From the President ............................ 2 David Johnson The Wheel ....................................... 3 Designed by: Erich Asperschlager The simple joy of being a kid is universal Special Thanks to: Deb DeCicco, X-MAN ........................................... 7 Melissa White, Kathy Waters, and Sarah Menard He’s come a long way Thank you to R.C. Brayshaw Away He Goes ................................ 10 and Company for their generous Mason’s journey is just beginning contribution toward production costs. rcbrayshaw.com Faces of Philanthropy ....................... 12 Horizons is the quarterly Snapshots ....................................... 13 magazine of Crotched Mountain, one of New Hampshire’s most respected non-profit organizations, dedicated to serving people with disabilities. Learn more at cmf.org. To support Crotched Mountain through a gift, visit cmf.org/give or call 603-831-8224. 1 | HORIZONS SPRING 2019 OUR SHARED STEPS The journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. We’ve been exposed to this famous quotation, I’m sure, thousands of times over the course of our travels. Perhaps we saw it embroidered on a home keepsake somewhere or it was shared with us by a good friend or maybe we heard it in a Willie Nelson song (“There Is No Easy Way (But There Is a Way),” Island in the Sea, 1987). The quote is attributed to the ancient Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu, and it has certainly withstood the test of time and is just as applicable now as it was in 500 B.C. And when you talk about what happens here at Crotched Mountain School on a daily basis, it is difficult for me to conjure a more apt characterization. -

The Acoustic City

The Acoustic City The Acoustic City MATTHEW GANDY, BJ NILSEN [EDS.] PREFACE Dancing outside the city: factions of bodies in Goa 108 Acoustic terrains: an introduction 7 Arun Saldanha Matthew Gandy Encountering rokesheni masculinities: music and lyrics in informal urban public transport vehicles in Zimbabwe 114 1 URBAN SOUNDSCAPES Rekopantswe Mate Rustications: animals in the urban mix 16 Music as bricolage in post-socialist Dar es Salaam 124 Steven Connor Maria Suriano Soft coercion, the city, and the recorded female voice 23 Singing the praises of power 131 Nina Power Bob White A beautiful noise emerging from the apparatus of an obstacle: trains and the sounds of the Japanese city 27 4 ACOUSTIC ECOLOGIES David Novak Cinemas’ sonic residues 138 Strange accumulations: soundscapes of late modernity Stephen Barber in J. G. Ballard’s “The Sound-Sweep” 33 Matthew Gandy Acoustic ecology: Hans Scharoun and modernist experimentation in West Berlin 145 Sandra Jasper 2 ACOUSTIC FLÂNERIE Stereo city: mobile listening in the 1980s 156 Silent city: listening to birds in urban nature 42 Heike Weber Joeri Bruyninckx Acoustic mapping: notes from the interface 164 Sonic ecology: the undetectable sounds of the city 49 Gascia Ouzounian Kate Jones The space between: a cartographic experiment 174 Recording the city: Berlin, London, Naples 55 Merijn Royaards BJ Nilsen Eavesdropping 60 5 THE POLITIcs OF NOISE Anders Albrechtslund Machines over the garden: flight paths and the suburban pastoral 186 3 SOUND CULTURES Michael Flitner Of longitude, latitude, and -

Law on Remote Islands: the Convergence of Fact and Fiction

Louisiana State University Law Center LSU Law Digital Commons Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2003 Law on Remote Islands: The Convergence of Fact and Fiction Joseph Bockrath Louisiana State University, Paul M. Hebert Law Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph Bockrath, Law on Remote Islands: The Convergence of Fact and Fiction, 27 Legal Studies Forum 21 (2003). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Wed Sep 11 10:31:28 2019 Citations: Bluebook 20th ed. Joseph Bockrath, Law on Remote Islands: The Convergence of Fact and Fiction, 27 Legal Stud. F. 21 (2003). APA 6th ed. Bockrath, J. (2003). Law on remote islands: The convergence of fact and fiction. Legal Studies Forum, 27(1), 21-82. ALWD Bockrath, J. (2003). Law on remote islands: The convergence of fact and fiction. Legal Stud. F., 27(1), 21-82. Chicago 7th ed. Joseph Bockrath, "Law on Remote Islands: The Convergence of Fact and Fiction," Legal Studies Forum 27, no. 1 (2003): 21-82 McGill Guide 9th ed. Joseph Bockrath, "Law on Remote Islands: The Convergence of Fact and Fiction" (2003) 27:1 Leg Studies Forum 21. MLA 8th ed. Bockrath, Joseph. "Law on Remote Islands: The Convergence of Fact and Fiction." Legal Studies Forum, vol. -

Fugitive Anne a Romance of the Unexplored Bush

Fugitive Anne A Romance of the Unexplored Bush Praed, Rosa Campbell (1851-1935) A digital text sponsored by Australian Literature Electronic Gateway University of Sydney Library Sydney, Australia 2002 http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/ozlit © University of Sydney Library. The texts and images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Source Text: Prepared from the print edition published by John Long, London 1902 All quotation marks are retained as data. First Published: 1902 Australian Etext Collections at women writers novels 1890-1909 Fugitive Anne A Romance of the Unexplored Bush London John Long 1902 Fugitive Anne - Part I Chapter I - The Closed Cabin IT was between nine and ten in the morning on board the Eastern and Australasian passenger boat Leichardt, which was steaming in a southerly direction over a calm, tropical sea between the Great Barrier Reef and the north-eastern shores of Australia. The boat was expected to arrive at Cooktown during the night, having last stopped at the newly-established station on Thursday Island. This puts time back a little over twenty years. The passengers' cabins on board the Leichardt opened for the most part off the saloon. Here, several people were assembled, for excitement had been aroused by the fact that the door of Mrs Bedo's cabin was locked, and that she had not been seen since the previous day. Mrs Bedo was the only first-class lady passenger on the Leichardt. Three men stood close to her cabin door. These were Captain Cass, the captain of the Leichardt; the ship's doctor, and Mr Elias Bedo, the lady's husband. -

1 a Critical Edition of the Hexaplaric Fragments Of

A CRITICAL EDITION OF THE HEXAPLARIC FRAGMENTS OF JOB 22-42 Introduction As a result of the Rich Seminar on the Hexapla in the summer of 1994 at Oxford, a decision was made to create a new collection and edition of all Hexaplaric fragments.1 Frederick Field was the last scholar to compile all known fragments in the mid to late 19th century,2 but by 1902, Henry Barclay Swete had announced that more hexaplaric materials were ―accumulating.‖3 These new materials need to be included in a new collection of hexaplaric fragments, a collection which is called ―a Field for the 21st century.‖4 With the publication of two-thirds of the critical editions of the Septuagint (LXX) by the Septuaginta-Unternehmen in Göttingen, the fulfillment of a new collection of all known hexaplaric fragments is becoming more feasible. Project 1 Alison Salvesen ed., Origen’s Hexapla and Fragments: Papers presented at the Rich Seminar on the Hexapla Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies, 25th-3rd August 1994 (Texte und Studien zum Antiken Judentum 58 Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1998), vi. 2 Frederick Field, Origenis Hexaplorum quae supersunt sive veterum interpretum graecorum in totum Vetus Testamentum fragmenta, 2 vols (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1875). 3 Henry Barclay Swete, An Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1902. Reprint, Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2003), 76. 4 See http://www.hexapla.org/. Accessed on 3/20/2010. The Hexapla Institute is a reality despite Sydney Jellicoe‘s pessimism concerning a revised and enlarged edition of the hexaplaric fragments, which he did not think was in the ―foreseeable future.‖ Sidney Jellicoe, The Septuagint and Modern Study (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968), 129. -

Correlations Between Old Aramaic Inscriptions and the Aramaic Section of Daniel

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 1987 Correlations Between Old Aramaic Inscriptions and the Aramaic Section of Daniel Zdravko Stefanovic Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Stefanovic, Zdravko, "Correlations Between Old Aramaic Inscriptions and the Aramaic Section of Daniel" (1987). Dissertations. 146. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/146 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps.