Fugitive Anne a Romance of the Unexplored Bush

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waiting for God by Simone Weil

WAITING FOR GOD Simone '111eil WAITING FOR GOD TRANSLATED BY EMMA CRAUFURD rwith an 1ntroduction by Leslie .A. 1iedler PERENNIAL LIBilAilY LIJ Harper & Row, Publishers, New York Grand Rapids, Philadelphia, St. Louis, San Francisco London, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto This book was originally published by G. P. Putnam's Sons and is here reprinted by arrangement. WAITING FOR GOD Copyright © 1951 by G. P. Putnam's Sons. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written per mission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address G. P. Putnam's Sons, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y.10016. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published in 1973 INTERNATIONAL STANDARD BOOK NUMBER: 0-06-{)90295-7 96 RRD H 40 39 38 37 36 35 34 33 32 31 Contents BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Vll INTRODUCTION BY LESLIE A. FIEDLER 3 LETTERS LETTER I HESITATIONS CONCERNING BAPTISM 43 LETTER II SAME SUBJECT 52 LETTER III ABOUT HER DEPARTURE s8 LETTER IV SPIRITUAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY 61 LETTER v HER INTELLECTUAL VOCATION 84 LETTER VI LAST THOUGHTS 88 ESSAYS REFLECTIONS ON THE RIGHT USE OF SCHOOL STUDIES WITII A VIEW TO THE LOVE OF GOD 105 THE LOVE OF GOD AND AFFLICTION 117 FORMS OF THE IMPLICIT LOVE OF GOD 1 37 THE LOVE OF OUR NEIGHBOR 1 39 LOVE OF THE ORDER OF THE WORLD 158 THE LOVE OF RELIGIOUS PRACTICES 181 FRIENDSHIP 200 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT LOVE 208 CONCERNING THE OUR FATHER 216 v Biographical 7\lote• SIMONE WEIL was born in Paris on February 3, 1909. -

Bestand Neuware(34563).Xlsx

Best.‐Nr. Künstler Album Preis release 0001 123 minut Les 19,00 € 0002 123 minut Les 19,00 € 0003 17 Hippies Anatomy 23,00 € 0004 A day to remember You're welcome (ltd.) 31,50 € Mrz. 21 0005 A day to remember You're welcome 23,00 € Mrz. 21 0006 Abba The studio albums 138,00 € 0007 Aborted Retrogore 20,00 € 0008 Abwärts V8 21,00 € Mrz. 21 0009 AC/DC Black Ice 20,00 € 0010 AC/DC Live At River Plate 28,50 € 0011 AC/DC Who made who 18,50 € 0012 AC/DC High voltage 19,00 € 0013 AC/DC Back in black 17,50 € 0014 AC/DC Who made who 15,00 € 0015 AC/DC Black ice 20,00 € 0016 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 CD Box 0017 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 CD Box 0018 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 CD Box 0019 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0020 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0021 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0022 AC/DC Power Up 27,50 € Nov. 20 0023 AC/DC Power Up 27,50 € Nov. 20 0024 AC/DC Power Up 27,50 € Nov. 20 0025 AC/DC Power Up 27,50 € Nov. 20 0026 AC/DC Power Up 27,50 € Nov. 20 0027 AC/DC High voltage 19,00 € Dez. 20 0028 AC/DC Highway to hell 20,00 € Dez. 20 0029 AC/DC Highway to hell 20,00 € Dez. -

Measurement System Evaluation for Upwind/Downwind Sampling of Fugitive Dust Emissions

Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 11: 331–350, 2011 Copyright © Taiwan Association for Aerosol Research ISSN: 1680-8584 print / 2071-1409 online doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2011.03.0028 Measurement System Evaluation for Upwind/Downwind Sampling of Fugitive Dust Emissions John G. Watson1,2*, Judith C. Chow1,2, Li Chen1, Xiaoliang Wang1, Thomas M. Merrifield3, Philip M. Fine4, Ken Barker5 1 Desert Research Institute, 2215 Raggio Parkway, Reno, NV, USA 89512 2 Institute of Earth Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 10 Fenghui South Road, Xi’an High-Tech Zone, Xi’an, China 710075 3 BGI Incorporated, 58 Guinan Street, Waltham, MA, USA, 02451 4 South Coast Air Quality Management District, 21865 Copley Drive, Diamond Bar, CA, USA 91765 5 Sully-Miller Contracting Co., 135 S. State College Boulevard, Brea, CA, USA 92821 ABSTRACT Eight different PM10 samplers with various size-selective inlets and sample flow rates were evaluated for upwind/ downwind assessment of fugitive dust emissions from two sand and gravel operations in southern California during September through October 2008. Continuous data were acquired at one-minute intervals for 24 hours each day. Integrated filters were acquired at five-hour intervals between 1100 and 1600 PDT on each day because winds were most consistent during this period. High-volume (hivol) size-selective inlet (SSI) PM10 Federal Reference Method (FRM) filter samplers were comparable to each other during side-by-side sampling, even under high dust loading conditions. Based on linear regression slope, the BGI low-volume (lovol) PQ200 FRM measured ~18% lower PM10 levels than a nearby hivol SSI in the source-dominated environment, even though tests in ambient environments show they are equivalent. -

Return to the Temple of Elemental Evil ERRATA and FAQ

Return to the Temple of Elemental Evil ERRATA AND FAQ A collaborative product of the members of Monte Cook's Return to the Temple of Elemental Evil web forum. Compiled, edited, and formatted by Siobharek. PDF version edited by ZansForCans. Modified: 11 February 2003 The definitive source for this errata and FAQ can be found in the ‘sticky’ threads at the top of the topic list on Monte Cook's Return to the Temple of Elemental Evil web forum. None of these errata or FAQ are official in any way (i.e. Monte or WotC have not said "That's right."), but most have been agreed to be accurate and true to the core rulebooks by many DMs running this adventure. NPC stats corrections are grouped in the appropriate chapter that the NPC appears in. In some cases, there is no ‘fix’ suggested—the errata is simply provided to alert you to a discrepancy. You didn’t think we’d do all the work for you, did you? It may seem like there are quite a lot of errata for this product. There are! Part of the explanation we have heard is that Monte was working on the adventure while D&D 3e was still being finalized. The rest we simply blame on his editors. ;) We welcome further corrections and additions to this list. However, when and if you find something that doesn't seem right, please check in every available rulebook. For instance, adding the right number of feats and stat increases to monsters with classes can be fiendishly hard but check it and double check it as much as you can. -

Egyptian Literature

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Egyptian Literature This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Egyptian Literature Release Date: March 8, 2009 [Ebook 28282] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK EGYPTIAN LITERATURE*** Egyptian Literature Comprising Egyptian Tales, Hymns, Litanies, Invocations, The Book Of The Dead, And Cuneiform Writings Edited And With A Special Introduction By Epiphanius Wilson, A.M. New York And London The Co-Operative Publication Society Copyright, 1901 The Colonial Press Contents Special Introduction. 2 The Book Of The Dead . 7 A Hymn To The Setting Sun . 7 Hymn And Litany To Osiris . 8 Litany . 9 Hymn To R ....................... 11 Hymn To The Setting Sun . 15 Hymn To The Setting Sun . 19 The Chapter Of The Chaplet Of Victory . 20 The Chapter Of The Victory Over Enemies. 22 The Chapter Of Giving A Mouth To The Overseer . 24 The Chapter Of Giving A Mouth To Osiris Ani . 24 Opening The Mouth Of Osiris . 25 The Chapter Of Bringing Charms To Osiris . 26 The Chapter Of Memory . 26 The Chapter Of Giving A Heart To Osiris . 27 The Chapter Of Preserving The Heart . 28 The Chapter Of Preserving The Heart . 29 The Chapter Of Preserving The Heart . 30 The Chapter Of Preserving The Heart . 30 The Heart Of Carnelian . 31 Preserving The Heart . 31 Preserving The Heart . -

Best-Nr. Künstler Album Preis Release 0001 100 Kilo Herz Weit Weg Von Zu Hause 17,50 € Mai

Best-Nr. Künstler Album Preis release 0001 100 Kilo Herz Weit weg von zu Hause 17,50 € Mai. 21 0002 100 Kilo Herz Stadt Land Flucht 19,00 € Jun. 21 0003 100 Kilo Herz Stadt Land Flucht 19,00 € Jun. 21 0004 100 Kilo Herz Weit weg von Zuhause 17,50 € Jun. 21 0005 100 Kilo Herz Weit weg von Zuhause 17,50 € Jun. 21 0006 123 minut Les 19,00 € 0007 123 minut Les 19,00 € 0008 17 Hippies Anatomy 23,00 € 0009 187 Straßenbande Sampler 5 26,00 € Mai. 21 0010 187 Straßenbande Sampler 5 26,00 € Mai. 21 0011 A day to remember You're welcome (ltd.) 31,50 € Mrz. 21 0012 A day to remember You're welcome 23,00 € Mrz. 21 0013 Abba The studio albums 138,00 € 0014 Aborted Retrogore 20,00 € 0015 Abwärts V8 21,00 € Mrz. 21 0016 AC/DC Black Ice 20,00 € 0017 AC/DC Live At River Plate 28,50 € 0018 AC/DC Who made who 18,50 € 0019 AC/DC High voltage 19,00 € 0020 AC/DC Back in black 17,50 € 0021 AC/DC Who made who 15,00 € 0022 AC/DC Black ice 20,00 € 0023 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 0024 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 0025 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 0026 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0027 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0028 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0029 AC/DC Power Up 27,50 € Nov. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessingiiUM-I the World's Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8812304 Comrades, friends and companions: Utopian projections and social action in German literature for young people, 1926-1934 Springman, Luke, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by Springman, Luke. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 COMRADES, FRIENDS AND COMPANIONS: UTOPIAN PROJECTIONS AND SOCIAL ACTION IN GERMAN LITERATURE FOR YOUNG PEOPLE 1926-1934 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Luke Springman, B.A., M.A. -

Virginian Writers Fugitive Verse

VIRGIN IAN WRITERS OF FUGITIVE VERSE VIRGINIAN WRITERS FUGITIVE VERSE we with ARMISTEAD C. GORDON, JR., M. A., PH. D, Assistant Proiesso-r of English Literature. University of Virginia I“ .‘ '. , - IV ' . \ ,- w \ . e. < ~\ ,' ’/I , . xx \ ‘1 ‘ 5:" /« .t {my | ; NC“ ‘.- ‘ '\ ’ 1 I Nor, \‘ /" . -. \\ ' ~. I -. Gil-T 'J 1’: II. D' VI. Doctor: .. _ ‘i 8 » $9793 Copyrighted 1923 by JAMES '1‘. WHITE & C0. :To MY FATHER ARMISTEAD CHURCHILL GORDON, A VIRGINIAN WRITER OF FUGITIVE VERSE. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. The thanks of the author are due to the following publishers, editors, and individuals for their kind permission to reprint the following selections for which they hold copyright: To Dodd, Mead and Company for “Hold Me Not False” by Katherine Pearson Woods. To The Neale Publishing Company for “1861-1865” by W. Cabell Bruce. To The Times-Dispatch Publishing Company for “The Land of Heart‘s Desire” by Thomas Lomax Hunter. To The Curtis Publishing Company for “The Lane” by Thomas Lomax Hunter (published in The Saturday Eve- ning Post, and copyrighted, 1923, by the Curtis Publishing 00.). To the Johnson Publishing Company for “Desolate” by Fanny Murdaugh Downing (cited from F. V. N. Painter’s Poets of Virginia). To Harper & Brothers for “A Mood” and “A Reed Call” by Charles Washington Coleman. To The Independent for “Life’s Silent Third”: by Charles Washington Coleman. To the Boston Evening Transcript for “Sister Mary Veronica” by Nancy Byrd Turner. To The Century for “Leaves from the Anthology” by Lewis Parke Chamberlayne and “Over the Sea Lies Spain” by Charles Washington Coleman. To Henry Holt and Company for “Mary‘s Dream” by John Lowe and “To Pocahontas” by John Rolfe. -

Eberron Jumpchain

Eberron Jumpchain By Jim the Hate Fish Welcome to the wonderful world of Eberron! Twelve moons hang in the sky, with a belt of shattered rocks suffusing it. The twelve Dragonmarked houses rule over all aspects of life, each sponsoring a member of the Twelve, wizards dedicated to keeping the peace. Swashbuckling rogues work alongside ingenious craftsmen, wielding swords and shield and automatic crossbows. Robotic soldiers, remnants of the last great war, tread the streets, living the closest they can to normal lives, albeit typically normal lives as mercenaries. Spellslingers craft works of true arcana, ships that travel the sky, trains fuelled by lightning, and stone tablets that can communicate over great distances. You have 1000CP to spend. In addition, you get an Origin, Race, Class and Starting Location for free, as well as being able to set your age and gender as you please. Starting Location You may either roll an eight-sided die, starting at the relevant location, or pay 50CP to choose. The location you start at within each given area is at your discretion. 1: Breland. Breland is one of the five nations of central Khorvaire, lying in the southwest of the continent enjoying one of the largest areas of the nations and territories. Breland is a mix of open farmland, woodland and sprawling metropolis, the most famous of which is Sharn. 2: The Mournland. Once, Cyre shone more brightly than any of its sibling nations in the kingdom of Galifar. The Last War took a toll on the nation and its citizens, until disaster struck. -

ARMED FORCES CIP: Taking a Sabbatical from Your Navy Career

Navy • Marine Corps • Coast Guard • Army • Air Force AT AT EASE ARMED FORCES San Diego Navy/Marine Corps Dispatch • www.armedforcesdispatch.com • 619.280.2985 FIFTY SIXTH YEAR NO. 30 Serving active duty and retired military personnel, veterans and civil service employees THURSDAY, JANUARY 26, 2017 by Jim Garamone fense secretary. Mattis retired from the Marine Corps in 2013. WASHINGTON - By a 98-1 vote, the Senate confirmed Marine Mattis is a veteran of the Gulf War and the wars in Iraq and Corps Gen. (Ret.) James Mattis to be secretary of defense Jan. Afghanistan. His military career culminated with service as com- 20, and Vice President Michael Pence administered his oath of mander of U.S. Central Command. office shortly afterward. The secretary was born in Richland, Wash., graduating from Mattis is the first retired general officer to hold the position high school there in 1968 and enlisting in the Marine Corps the since General of the Army George C. Marshall in the early 1950s. following year. He was commissioned in the Marine Corps in 1972 Congress passed a waiver for the retired four-star general to serve after graduating from Central Washington University. in the position, because law requires former service members to have been out of uniform for at least seven years to serve as de- Mattis said his priority as defense sec- retary will be to strengthen military readiness, strengthen U.S. alliances and bring business reforms to the Defense Department. He served as a rifle and weapons platoon commander, and as a lieutenant colonel, he commanded the 1st Battalion, 7th Ma- rines in Operation Desert Storm. -

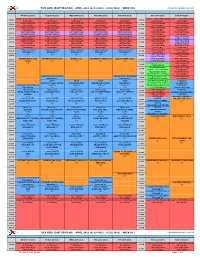

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM MON (4/12/2021) TUE (4/13/2021) WED (4/14/2021) THU (4/15/2021) FRI (4/16/2021) SAT (4/17/2021) SUN (4/18/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO -

Sympathy for the Devil: Volatile Masculinities in Recent German and American Literatures

Sympathy for the Devil: Volatile Masculinities in Recent German and American Literatures by Mary L. Knight Department of German Duke University Date:_____March 1, 2011______ Approved: ___________________________ William Collins Donahue, Supervisor ___________________________ Matthew Cohen ___________________________ Jochen Vogt ___________________________ Jakob Norberg Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of German in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 ABSTRACT Sympathy for the Devil: Volatile Masculinities in Recent German and American Literatures by Mary L. Knight Department of German Duke University Date:_____March 1, 2011_______ Approved: ___________________________ William Collins Donahue, Supervisor ___________________________ Matthew Cohen ___________________________ Jochen Vogt ___________________________ Jakob Norberg An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of German in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 Copyright by Mary L. Knight 2011 Abstract This study investigates how an ambivalence surrounding men and masculinity has been expressed and exploited in Pop literature since the late 1980s, focusing on works by German-speaking authors Christian Kracht and Benjamin Lebert and American author Bret Easton Ellis. I compare works from the United States with German and Swiss novels in an attempt to reveal the scope – as well as the national particularities – of these troubled gender identities and what it means in the context of recent debates about a “crisis” in masculinity in Western societies. My comparative work will also highlight the ways in which these particular literatures and cultures intersect, invade, and influence each other. In this examination, I demonstrate the complexity and success of the critical projects subsumed in the works of three authors too often underestimated by intellectual communities.