Sympathy for the Devil: Volatile Masculinities in Recent German and American Literatures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

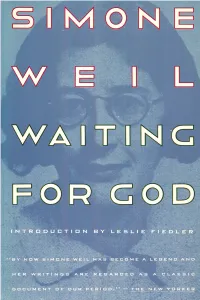

Waiting for God by Simone Weil

WAITING FOR GOD Simone '111eil WAITING FOR GOD TRANSLATED BY EMMA CRAUFURD rwith an 1ntroduction by Leslie .A. 1iedler PERENNIAL LIBilAilY LIJ Harper & Row, Publishers, New York Grand Rapids, Philadelphia, St. Louis, San Francisco London, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto This book was originally published by G. P. Putnam's Sons and is here reprinted by arrangement. WAITING FOR GOD Copyright © 1951 by G. P. Putnam's Sons. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written per mission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address G. P. Putnam's Sons, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y.10016. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published in 1973 INTERNATIONAL STANDARD BOOK NUMBER: 0-06-{)90295-7 96 RRD H 40 39 38 37 36 35 34 33 32 31 Contents BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Vll INTRODUCTION BY LESLIE A. FIEDLER 3 LETTERS LETTER I HESITATIONS CONCERNING BAPTISM 43 LETTER II SAME SUBJECT 52 LETTER III ABOUT HER DEPARTURE s8 LETTER IV SPIRITUAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY 61 LETTER v HER INTELLECTUAL VOCATION 84 LETTER VI LAST THOUGHTS 88 ESSAYS REFLECTIONS ON THE RIGHT USE OF SCHOOL STUDIES WITII A VIEW TO THE LOVE OF GOD 105 THE LOVE OF GOD AND AFFLICTION 117 FORMS OF THE IMPLICIT LOVE OF GOD 1 37 THE LOVE OF OUR NEIGHBOR 1 39 LOVE OF THE ORDER OF THE WORLD 158 THE LOVE OF RELIGIOUS PRACTICES 181 FRIENDSHIP 200 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT LOVE 208 CONCERNING THE OUR FATHER 216 v Biographical 7\lote• SIMONE WEIL was born in Paris on February 3, 1909. -

Mothers Grimm Kindle

MOTHERS GRIMM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Danielle Wood | 224 pages | 01 Oct 2016 | Allen & Unwin | 9781741756746 | English | St Leonards, Australia Mothers Grimm PDF Book Showing An aquatic reptilian-like creature that is an exceptional swimmer. They have a temper that they control and release to become effective killers, particularly when a matter involves a family member or loved one. She took Nick to Weston's car and told Nick that he knew Adalind was upstairs with Renard, and the two guys Weston sent around back knew too. When Wu asks how she got over thinking it was real, she tells him that it didn't matter whether it was real, what mattered was losing her fear of it. Dick Award Nominee I found the characters appealing, and the plot intriguing. This wesen is portrayed as the mythological basis for the Three Little Pigs. The tales are very dark, and while the central theme is motherhood, the stories are truly about womanhood, and society's unrealistic and unfair expectations of all of us. Paperback , pages. The series presents them as the mythological basis for The Story of the Three Bears. In a phone call, his parents called him Monroe, seeming to indicate that it is his first name. The first edition contained 86 stories, and by the seventh edition in , had unique fairy tales. Danielle is currently teaching creative writing at the University of Tasmania. The kiss of a musai secretes a psychotropic substance that causes obsessive infatuation. View all 3 comments. He asks Sean Renard, a police captain, to endorse him so he would be elected for the mayor position. -

3. IRAN Christian Kracht, 1979 (2001) Popkultur Und Fundamentalismus I

3. IRAN Christian Kracht, 1979 (2001) Popkultur und Fundamentalismus I Den Titel seines Romans hat Christian Kracht gut gewählt. Das Jahr 1979 mar- kiert einen Umschwung in der Wahrnehmung des Orients durch den Westen. Zafer Şenocak, ein Grenzgänger zwischen den Kulturen, schreibt dazu: Bis 1979 – dem Jahr der islamischen Revolution im Iran – spielte der Islam auf der Weltbühne keine politisch herausragende Rolle. Er war bestenfalls tiefenpsycholo- gisch wirksam, als hemmender Faktor bei Modernisierungsbestrebungen in den muslimischen Ländern, im Zuge der Säkularisierung der Gesellschaft, beiseite ge- schoben von der westlich orientierten Elite dieser Länder. In Europa wurden die Gesichter des Islam zu Ornamenten einer sich nach Abwechslung und Fremde seh- nenden Zivilisation. Das Fremde im Islam war Identitätsspender, Kulminations- punkt von Distanzierung und Anziehung zugleich.1 Im Iran kündigten sich 1975 die ersten Unruhen an, als Schah Pahlavi das beste- hende Zweiparteiensystem auflöste und nur noch seine sogenannte Erneuerungs- partei zuließ.2 Oppositionsgruppen gab es aber nach wie vor, und die andauernde 01Zafer Şenocak, War Hitler Araber? IrreFührungen an den Rand Europas (Berlin: Babel, 1994). Die fiktionale Literatur, die sich aus iranischer Sicht mit der Revolution von 1979 und ihren Folgen beschäftigt, ist umfangreich. Zwei Titel seien genannt, weil sie von iranischen Autorinnen stam- men, die für ein westliches Publikum schreiben. Beide lehren inzwischen in den USA als Hoch- schulprofessorinnen: Azar Nafisi, Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books (New York: Ran- dom House, 2003) und Fatemeh Keshavarz, Jasmine and Stars: Reading More than Lolita in Tehran (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007). Letzteres Buch versteht sich als Kritik an ersterem: Keshavarz wirft Nafisi eine Simplifizierung im Sinne des Opfer-Täter- Schemas und Reduktionismus vor. -

Posting Selfies and Body Image in Young Adult Women: the Selfie Paradox

Posting selfies and body image in young adult women: The selfie paradox. Item Type Article Authors Grogan, Sarah; Rothery, Leonie; Cole, Jenny; Hall, Matthew Citation Grogan, S., Rothery, L., Cole, J. & Hall, M. (2018). Posting selfies and body image in young adult women: The selfie paradox. Journal of Social Media in Society, 7(1), 15-36. Publisher Tarleton State University Journal The Journal of Social Media in Society Download date 28/09/2021 07:51:29 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10545/622743 The Journal of Social Media in Society Spring 2018, Vol. 7, No. 1, Pages 15-36 thejsms.org Posting Selfies and Body Image in Young Adult Women: The Selfie Paradox Sarah Grogan1*, Leonie Rothery1, Jennifer Cole1, and Matthew Hall2 1Department of Psychology, Manchester Metropolitan University, 53 Bonsall Street, Manchester, UK, M15 6GX. 2Faculty of Life & Health Sciences, Ulster University, Cromore Road, Coleraine, BT52 1SA; College of Business, Law & Social Sciences, University of Derby, Kedleston Rd, Derby DE22 1GB. *Corresponding Author: [email protected], (044)1612472504. This exploratory study was designed to investigate Women differentiated between their “unreal,” how young women make sense of their decision to digitally manipulated online selfie identity and their post selfies, and perceived links between selfie “real” identity outside of Facebook and Instagram. posting and body image. Eighteen 19-22 year old Bodies were expected to be covered, and sexualised British women were interviewed about their selfies were to be avoided. Results challenge experiences of taking and posting selfies, and conceptualisations of women as empowered and self- interviews were analysed using inductive thematic determined selfie posters; although women sought to analysis. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Measurement System Evaluation for Upwind/Downwind Sampling of Fugitive Dust Emissions

Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 11: 331–350, 2011 Copyright © Taiwan Association for Aerosol Research ISSN: 1680-8584 print / 2071-1409 online doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2011.03.0028 Measurement System Evaluation for Upwind/Downwind Sampling of Fugitive Dust Emissions John G. Watson1,2*, Judith C. Chow1,2, Li Chen1, Xiaoliang Wang1, Thomas M. Merrifield3, Philip M. Fine4, Ken Barker5 1 Desert Research Institute, 2215 Raggio Parkway, Reno, NV, USA 89512 2 Institute of Earth Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 10 Fenghui South Road, Xi’an High-Tech Zone, Xi’an, China 710075 3 BGI Incorporated, 58 Guinan Street, Waltham, MA, USA, 02451 4 South Coast Air Quality Management District, 21865 Copley Drive, Diamond Bar, CA, USA 91765 5 Sully-Miller Contracting Co., 135 S. State College Boulevard, Brea, CA, USA 92821 ABSTRACT Eight different PM10 samplers with various size-selective inlets and sample flow rates were evaluated for upwind/ downwind assessment of fugitive dust emissions from two sand and gravel operations in southern California during September through October 2008. Continuous data were acquired at one-minute intervals for 24 hours each day. Integrated filters were acquired at five-hour intervals between 1100 and 1600 PDT on each day because winds were most consistent during this period. High-volume (hivol) size-selective inlet (SSI) PM10 Federal Reference Method (FRM) filter samplers were comparable to each other during side-by-side sampling, even under high dust loading conditions. Based on linear regression slope, the BGI low-volume (lovol) PQ200 FRM measured ~18% lower PM10 levels than a nearby hivol SSI in the source-dominated environment, even though tests in ambient environments show they are equivalent. -

Arizona 500 2021 Final List of Songs

ARIZONA 500 2021 FINAL LIST OF SONGS # SONG ARTIST Run Time 1 SWEET EMOTION AEROSMITH 4:20 2 YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG AC/DC 3:28 3 BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY QUEEN 5:49 4 KASHMIR LED ZEPPELIN 8:23 5 I LOVE ROCK N' ROLL JOAN JETT AND THE BLACKHEARTS 2:52 6 HAVE YOU EVER SEEN THE RAIN? CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL 2:34 7 THE HAPPIEST DAYS OF OUR LIVES/ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL PART TWO ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL PART TWO 5:35 8 WELCOME TO THE JUNGLE GUNS N' ROSES 4:23 9 ERUPTION/YOU REALLY GOT ME VAN HALEN 4:15 10 DREAMS FLEETWOOD MAC 4:10 11 CRAZY TRAIN OZZY OSBOURNE 4:42 12 MORE THAN A FEELING BOSTON 4:40 13 CARRY ON WAYWARD SON KANSAS 5:17 14 TAKE IT EASY EAGLES 3:25 15 PARANOID BLACK SABBATH 2:44 16 DON'T STOP BELIEVIN' JOURNEY 4:08 17 SWEET HOME ALABAMA LYNYRD SKYNYRD 4:38 18 STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN LED ZEPPELIN 7:58 19 ROCK YOU LIKE A HURRICANE SCORPIONS 4:09 20 WE WILL ROCK YOU/WE ARE THE CHAMPIONS QUEEN 4:58 21 IN THE AIR TONIGHT PHIL COLLINS 5:21 22 LIVE AND LET DIE PAUL MCCARTNEY AND WINGS 2:58 23 HIGHWAY TO HELL AC/DC 3:26 24 DREAM ON AEROSMITH 4:21 25 EDGE OF SEVENTEEN STEVIE NICKS 5:16 26 BLACK DOG LED ZEPPELIN 4:49 27 THE JOKER STEVE MILLER BAND 4:22 28 WHITE WEDDING BILLY IDOL 4:03 29 SYMPATHY FOR THE DEVIL ROLLING STONES 6:21 30 WALK THIS WAY AEROSMITH 3:34 31 HEARTBREAKER PAT BENATAR 3:25 32 COME TOGETHER BEATLES 4:06 33 BAD COMPANY BAD COMPANY 4:32 34 SWEET CHILD O' MINE GUNS N' ROSES 5:50 35 I WANT YOU TO WANT ME CHEAP TRICK 3:33 36 BARRACUDA HEART 4:20 37 COMFORTABLY NUMB PINK FLOYD 6:14 38 IMMIGRANT SONG LED ZEPPELIN 2:20 39 THE -

Impact of a Psychology of Masculinities Course on Women's Attitudes Toward Male Gender Roles

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Winter 3-25-2015 Impact of a Psychology of Masculinities Course on Women's Attitudes toward Male Gender Roles Sylvia Marie Ferguson Kidder Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Gender and Sexuality Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Kidder, Sylvia Marie Ferguson, "Impact of a Psychology of Masculinities Course on Women's Attitudes toward Male Gender Roles" (2015). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2210. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2207 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Impact of a Psychology of Masculinities Course on Women’s Attitudes toward Male Gender Roles by Sylvia Marie Ferguson Kidder A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Psychology Thesis Committee: Eric Mankowski, Chair Kerth O’Brien Kimberly Kahn Portland State University 2015 © 2015 Sylvia Marie Ferguson Kidder i Abstract Individuals are involved in an ongoing construction of gender ideology from two opposite but intertwined directions: they experience pressure to follow gender role norms, and they also participate in the social construction of these norms. An individual’s appraisal, positive or negative, of gender roles is called a “gender role attitude.” These lie on a continuum from traditional to progressive. -

'2009 MTV Movie Awards' Honors Ben Stiller with 'MTV Generation Award'

'2009 MTV Movie Awards' Honors Ben Stiller With 'MTV Generation Award' Premiering LIVE Sunday, May 31, 2009 at 9pm ET/8pm CT From The Gibson Amphitheatre in Universal City, CA SANTA MONICA, Calif., May 22 -- The 2009 MTV Movie Awards pays tribute to Ben Stiller with the coveted "MTV Generation Award" for his amazing contribution to Hollywood and for entertaining the MTV audience for years. From generation to generation, Ben Stiller has kept fans rolling with laughter since bursting onto the scene in Reality Bites and his early film roles and cult classics such as There's Something About Mary, Meet the Parents, Dodgeball: A True Underdog Story, Tropic Thunder and now this summer's eagerly anticipated Night at the Museum: Battle at the Smithsonian in theaters May 22, 2009. The "MTV Generation Award" is the MTV Movie Awards' highest honor, acknowledging an actor who has captured the attention of the MTV audience throughout his or her career. Past recipients include Adam Sandler, Mike Myers, Tom Cruise and Jim Carrey. Hosted by Andy Samberg, the 2009 MTV Movie Awards will be broadcast LIVE from the Gibson Amphitheatre in Universal City, CA on Sunday, May 31st at 9p.m. ET/8p.m. CT. "From The Royal Tenenbaums to Zoolander, Ben is a comedic chameleon, able to make the leap between drama and full-out comedy while maintaining his own unique brand of subversive humor," said Van Toffler, President of MTV Networks Music/Logo/Film Group. "That versatility and talent has earned him legions of devoted fans over the years which makes him a perfect recipient for the 'MTV Generation Award.' Whether it's fighting a monkey in a museum or licking a decapitated head, nothing is ever off-limits for him and that's the type of warped creative vision and commitment MTV loves to reward." "I am honored to be getting the 'Generation Award,'" said Ben Stiller. -

KNIGHT Wake Forest University

Forbidden Fruit Civil Savagery in Christian Kracht’s Imperium “Ich war ein guter Gefangener. Ich habe nie Menschenfleisch gegessen.” I was a good prisoner. I never ate human flesh. These final words of Christian Kracht’s second novel, 1979, represent the last shred of dignity retained by the German protagonist, who is starving to death in a Chinese prison camp in the title year. Over and over, Kracht shows us a snapshot of what happens to the over-civilized individual when civilization breaks down. Faserland’s nameless narrator stands at the water’s edge, preparing to drown rather than live with his guilt and frustration; even the portrait of Kracht on the cover of his edited volume Mesopotamia depicts Kracht himself in a darkened wilderness, wearing a polo shirt and carrying an AK-47. In each of these moments, raw nature inspires the human capacity for violence and self-destruction as a sort of ironic antidote to the decadence and vacuity of a society in decline. Kracht’s latest novel, Imperium, further explicates this moment of annihilation. The story follows the fin-de-siècle adventures of real-life eccentric August Engelhardt, a Nuremberger who wears his hair long, promotes nudism, and sets off for the German colony of New Guinea in hopes of founding a cult of sun-worshippers and cocovores (i.e., people who subsist primarily on coconuts). Engelhardt establishes a coconut plantation near the small town of Herbertshöhe, where he attempts to practice his beliefs in the company of a series of companions of varying worth and, finally, in complete solitude. -

German Studies Association Newsletter ______

______________________________________________________________________________ German Studies Association Newsletter __________________________________________________________________ Volume XLIV Number 1 Spring 2019 German Studies Association Newsletter Volume XLIV Number 1 Spring 2019 __________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents Letter from the President ............................................................................................................... 2 Letter from the Executive Director ................................................................................................. 5 Conference Details .......................................................................................................................... 8 Conference Highlights ..................................................................................................................... 9 Election Results Announced ......................................................................................................... 14 A List of Dissertations in German Studies, 2017-19 ..................................................................... 16 Letter from the President Dear members and friends of the GSA, To many of us, “the GSA” refers principally to a conference that convenes annually in late September or early October in one city or another, and which provides opportunities to share ongoing work, to network with old and new friends and colleagues. And it is all of that, for sure: a forum for -

The Open Notebook’S Pitch Database Includes Dozens of Successful Pitch Letters for Science Stories

Selected Readings Prepared for the AAAS Mass Media Science & Engineering Fellows, May 2012 All contents are copyrighted and may not be used without permission. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION PART ONE: FINDING IDEAS 1. Lost and found: How great non-fiction writers discover great ideas—In this topical feature, TON guest contributor Brendan Borrell interviews numerous science writers about how they find ideas. (The short answer: In the darndest places.) 2. Ask TON: Saving string—Writers and editors provide advice on gathering ideas for feature stories. 3. Ask TON: From idea to story—Four experienced science writers share the questions they ask themselves when weighing whether a story idea is viable. 4. Ask TON: Finding international stories—Six well-traveled science writers share their methods for sussing out international stories. PART TWO: PITCHING 5. Ask TON: How to pitch—In this interview, writers and editors dispense advice on elements of a good pitch letter. 6. Douglas Fox recounts an Antarctic adventure—Doug Fox pitched his Antarctica story to numerous magazines, unsuccessfully, before finding a taker just before leaving on the expedition he had committed to months before. After returning home, that assignment fell through, and Fox pitched it one more time—to Discover, who bought the story. In this interview, Fox describes the lessons he learned in the pitching process; he also shares his pitch letters, both unsuccessful and successful (see links). 7. Pitching errors: How not to pitch—In this topical feature, Smithsonian editor Laura Helmuth conducts a roundtable conversation with six other editors in which they discuss how NOT to pitch.