69-18397 NEMANIC, Gerald Carl, 1941

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Odyssey-Greek-Translation.Pdf

05_273-611_Homer 2/Aesop 7/10/00 1:25 PM Page 273 HOMER / The Odyssey, Book One 273 THE ODYSSEY Translated by Robert Fitzgerald The ten-year war waged by the Greeks against Troy, culminating in the overthrow of the city, is now itself ten years in the past. Helen, whose flight to Troy with the Trojan prince Paris had prompted the Greek expedition to seek revenge and reclaim her, is now home in Sparta, living harmoniously once more with her husband Meneláos (Menelaus). His brother Agamémnon, commander in chief of the Greek forces, was murdered on his return from the war by his wife and her paramour. Of the Greek chieftains who have survived both the war and the perilous homeward voyage, all have returned except Odysseus, the crafty and astute ruler of Ithaka (Ithaca), an island in the Ionian Sea off western Greece. Since he is presumed dead, suitors from Ithaka and other regions have overrun his house, paying court to his attractive wife Penélopê, endangering the position of his son, Telémakhos (Telemachus), corrupting many of the servants, and literally eating up Odysseus’ estate. Penélopê has stalled for time but is finding it increasingly difficult to deny the suitors’ demands that she marry one of them; Telémakhos, who is just approaching young manhood, is becom- ing actively resentful of the indignities suffered by his household. Many persons and places in the Odyssey are best known to readers by their Latinized names, such as Telemachus. The present translator has used forms (Telémakhos) closer to the Greek spelling and pronunciation. -

Download Oxfordshire Music Scene 29 (3.7 Mb Pdf)

ISSUE 29 / JULY 2014 / FREE @omsmagazine INSIDE LEWIS WATSON WOOD & THE PUNT REVIEWED 2014 FESTIVAL GUIDE AUDIOSCOPE ECHO & THE BUNNYMEN AND MORE! GAZ COOMBES helicopters at glastonbury, new album and south park return NEWS news y v l Oxford Oxford is a new three day event for the city, happening i g O over the weekend of 26 to 28 September. The entertainment varies w e r over the weekend, exploring the four corners of the music, arts d n A and culture world. Friday’s theme is film/shows ( Grease sing-along and Alice In Wonderland ), Saturday, a more rock - ’n’roll vibe, with former Supergrass, now solo, mainstay, Gaz Coombes, returning to his old stomping ground, as well as a selection of names from the local and national leftfield like Tunng, Pixel Fix and Dance a la Plage with much more to be announced. Sunday is a free community event involving, so far, Dancin’ Oxford and Museum of Oxford and many more. t Community groups, businesses and sports clubs wishing to t a r P get involved should get in touch via the event website n a i r oxfordoxford.co.uk. Tickets are on sale now via the website SIMPLESIMPLMPLLEE d A with a discounted weekend ticket available to Oxford residents. MINDSMMININDS Audioscope have released two WITH MELANIEMELANMELANIE C albums of exclusives and rarities AND MARCMARC ALMONDALMOND which are available to download right now. Music for a Good Home 3 consists of 31 tracks from internationally known acts including: Amon Tobin, John Parish, Future of the Left, The Original Rabbit Foot Spasm Band, Oli from Stornoway’s Esben & the Witch, Thought Forms, Count Drachma (both pictured) and Aidan Skylarkin’ are all on Chrome Hoof, Tall Firs and many music bill for this year’s Cowley Carnival , now in its 14th year, more. -

Deconstructing Los Angeles Or a Secret Fax from Magritte Regarding Postliterate Legal Reasoning: a Critique of Legal Education

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 26 1992 Deconstructing Los Angeles or a Secret Fax from Magritte Regarding Postliterate Legal Reasoning: A Critique of Legal Education C. Garrison Lepow Loyola University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Legal Education Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation C. G. Lepow, Deconstructing Los Angeles or a Secret Fax from Magritte Regarding Postliterate Legal Reasoning: A Critique of Legal Education, 26 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 69 (1992). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol26/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DECONSTRUCTING LOS ANGELES OR A SECRET FAX FROM MAGRITTE REGARDING POSTLITERATE LEGAL REASONING: A CRITIQUE OF LEGAL EDUCATION C. Garrison Lepow* Not only is it clear that most law students become impatient at some point during their three years of formal education, but it is clear also that how students learn the law is more the cause of their impatience than what they learn.' Moreover, others besides law students may be entitled to challenge the style of education that manufactures a lawyer-culture. If one assumes for the sake of argument that the intellectual processes of lawyers, and consequently their values, differ from those of their society, this fact does not explain the difference between legal thinking and regular thinking, or explain why there should not be harmony between the two. -

SPRING 2019 Horizons Table of Contents Spring 2019 Written and Photographed By: from the President

HORIZONS SPRING 2019 Horizons Table of Contents Spring 2019 Written and Photographed by: From the President ............................ 2 David Johnson The Wheel ....................................... 3 Designed by: Erich Asperschlager The simple joy of being a kid is universal Special Thanks to: Deb DeCicco, X-MAN ........................................... 7 Melissa White, Kathy Waters, and Sarah Menard He’s come a long way Thank you to R.C. Brayshaw Away He Goes ................................ 10 and Company for their generous Mason’s journey is just beginning contribution toward production costs. rcbrayshaw.com Faces of Philanthropy ....................... 12 Horizons is the quarterly Snapshots ....................................... 13 magazine of Crotched Mountain, one of New Hampshire’s most respected non-profit organizations, dedicated to serving people with disabilities. Learn more at cmf.org. To support Crotched Mountain through a gift, visit cmf.org/give or call 603-831-8224. 1 | HORIZONS SPRING 2019 OUR SHARED STEPS The journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. We’ve been exposed to this famous quotation, I’m sure, thousands of times over the course of our travels. Perhaps we saw it embroidered on a home keepsake somewhere or it was shared with us by a good friend or maybe we heard it in a Willie Nelson song (“There Is No Easy Way (But There Is a Way),” Island in the Sea, 1987). The quote is attributed to the ancient Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu, and it has certainly withstood the test of time and is just as applicable now as it was in 500 B.C. And when you talk about what happens here at Crotched Mountain School on a daily basis, it is difficult for me to conjure a more apt characterization. -

The Acoustic City

The Acoustic City The Acoustic City MATTHEW GANDY, BJ NILSEN [EDS.] PREFACE Dancing outside the city: factions of bodies in Goa 108 Acoustic terrains: an introduction 7 Arun Saldanha Matthew Gandy Encountering rokesheni masculinities: music and lyrics in informal urban public transport vehicles in Zimbabwe 114 1 URBAN SOUNDSCAPES Rekopantswe Mate Rustications: animals in the urban mix 16 Music as bricolage in post-socialist Dar es Salaam 124 Steven Connor Maria Suriano Soft coercion, the city, and the recorded female voice 23 Singing the praises of power 131 Nina Power Bob White A beautiful noise emerging from the apparatus of an obstacle: trains and the sounds of the Japanese city 27 4 ACOUSTIC ECOLOGIES David Novak Cinemas’ sonic residues 138 Strange accumulations: soundscapes of late modernity Stephen Barber in J. G. Ballard’s “The Sound-Sweep” 33 Matthew Gandy Acoustic ecology: Hans Scharoun and modernist experimentation in West Berlin 145 Sandra Jasper 2 ACOUSTIC FLÂNERIE Stereo city: mobile listening in the 1980s 156 Silent city: listening to birds in urban nature 42 Heike Weber Joeri Bruyninckx Acoustic mapping: notes from the interface 164 Sonic ecology: the undetectable sounds of the city 49 Gascia Ouzounian Kate Jones The space between: a cartographic experiment 174 Recording the city: Berlin, London, Naples 55 Merijn Royaards BJ Nilsen Eavesdropping 60 5 THE POLITIcs OF NOISE Anders Albrechtslund Machines over the garden: flight paths and the suburban pastoral 186 3 SOUND CULTURES Michael Flitner Of longitude, latitude, and -

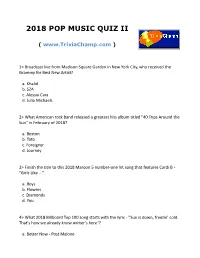

2018 Pop Music Quiz Ii

2018 POP MUSIC QUIZ II ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> Broadcast live from Madison Square Garden in New York City, who received the Grammy for Best New Artist? a. Khalid b. SZA c. Alessia Cara d. Julia Michaels 2> What American rock band released a greatest hits album titled "40 Trips Around the Sun" in February of 2018? a. Boston b. Toto c. Foreigner d. Journey 3> Finish the title to this 2018 Maroon 5 number-one hit song that features Cardi B - "Girls Like ...". a. Boys b. Flowers c. Diamonds d. You 4> What 2018 Billboard Top 100 song starts with the lyric - "Sun is down, freezin' cold. That's how we already know winter's here"? a. Better Now - Post Malone b. Nice For What - Drake c. Youngblood - 5 Seconds of Summer d. Sicko Mode - Travis Scott 5> Which American rapper had Billboard hits with the songs "Kamikaze", "The Ringer" and "Fall" in 2018? a. Lil Wayne b. Eminem c. Tupac Shakur d. 50 Cent 6> On the Billboard Hot Rock Songs chart in 2018, finish the title to this "Greta Van Fleet" hit song - "When the ...". a. Moneys Gone b. Sun Comes Down c. Levee Breaks d. Curtain Falls 7> Known as the "Queen of Soul", what artist died after a long battle with pancreatic cancer in August of 2018? a. Whitney Houston b. Aretha Franklin c. Patti LaBelle d. Tina Turner 8> Released on her debut studio album "Expectations", which American singer had a hit with the song "I'm a Mess"? a. Rita Ora b. Bebe Rexha c. -

The War on Drugs: Dream World

The War on Drugs: Dream World 4 The War on0 Drugs: Dream World By Michael Tedder Contributor on 03.10.14 in Features “One more round,” Adam Granduciel yells, hand in the air. He steps back into the batting cage and, just like the last few times, most of the balls he hits go straight up to the top of the net. I’m not entirely sure how one “wins” at a batting cage, but I’m fairly certain that’s not it. The cage in question, Philadelphia’s Everybody Hits, has been, at various times in its history, a silent-movie Lost In The Dream theater, a dirty-movie theater and a popular location for The War On Drugs wedding receptions. Looking at the wooden floors, I 2014 | Secretly Canadian / SC Distrib… doubt they’ve been cleaned since the silent-movie era. Buy Now There’s a distressed wall completely covered with baseball cards and two pinball machines in the back, though only the 1983 Sega Championship Pinball game has both flippers. A few neighborhood kids are running around, one of whom grabs my tape recorder mid-interview to ask me what it is. An iPod is pumping out a Pavement playlist, and a True Value sign hangs on the right wall. I’ve come to Everybody Hits to watch the War on Drugs hit a few balls, and to get some insight into the making of their third album Lost in the Dream, a monumental testament to the enduring power of American rock and roll, and the infinite possibilities for mutation contained therein. -

Law on Remote Islands: the Convergence of Fact and Fiction

Louisiana State University Law Center LSU Law Digital Commons Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2003 Law on Remote Islands: The Convergence of Fact and Fiction Joseph Bockrath Louisiana State University, Paul M. Hebert Law Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph Bockrath, Law on Remote Islands: The Convergence of Fact and Fiction, 27 Legal Studies Forum 21 (2003). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Wed Sep 11 10:31:28 2019 Citations: Bluebook 20th ed. Joseph Bockrath, Law on Remote Islands: The Convergence of Fact and Fiction, 27 Legal Stud. F. 21 (2003). APA 6th ed. Bockrath, J. (2003). Law on remote islands: The convergence of fact and fiction. Legal Studies Forum, 27(1), 21-82. ALWD Bockrath, J. (2003). Law on remote islands: The convergence of fact and fiction. Legal Stud. F., 27(1), 21-82. Chicago 7th ed. Joseph Bockrath, "Law on Remote Islands: The Convergence of Fact and Fiction," Legal Studies Forum 27, no. 1 (2003): 21-82 McGill Guide 9th ed. Joseph Bockrath, "Law on Remote Islands: The Convergence of Fact and Fiction" (2003) 27:1 Leg Studies Forum 21. MLA 8th ed. Bockrath, Joseph. "Law on Remote Islands: The Convergence of Fact and Fiction." Legal Studies Forum, vol. -

Download This Issue (PDF)

IS TODAY THE DAY YOU IGNITE YOUR FUTURE? If you have the spark, we have the programs to guide you toward a rewarding career. FORTIS offers programs in the following areas: Nursing • Medical/Dental • Business I.T. • Skilled Trades • Cosmetology CALL 1.800.555.7600 TEXT “IGNITE” TO 367847 FORTIS.EDU IGNITE YOUR FUTURE FORTIS INSTITUTE 5757 WEST 26TH STREET, ERIE, PA 16506 Financial Aid Available for those who qualify. Career Placement Assistance for All Graduates. For consumer information, visit Fortis.edu. 2 | Erie Reader | ErieReader.com December 24, 2014 CONTENT — DEC. 24, 2014 From the Editors ear’s end always seems to On State Street,” Rick Filippi rumi- be a time of reflection and nates of the City of Erie’s Christmas Yanalysis — a measuring of gift — or lump of coal depending on both the last twelve month’s high how you look at it: A tax increase and low points, an opportune time to the tune of 7.3 percent, bringing Features to evaluate the last 365 days to the total percentage increase since make sense of them as a collective 2012 to more than 21 percent. 8 — Tom Wolf Q&A whole. So as 2014 draws to a close To deal with an increasing budget, and we put the final touches on the raising taxes is the easy answer, An Interview with Pa.’s New Governor fourth volume of the Erie Reader, but as we continue to burden those you’ll find such contemplation and choosing to live within the City, is it consideration in the final issue of the right one? Shouldn’t our politi- Editors-in-Chief: 11 — 2014 Year In Review this volume. -

Both Slates Charged for Campaign Violations Referendum to Appear

VOLUME 47, ISSUE 44 THURSDAY, APRIL 10, 2014 WWW.UCSDGUARDIAN.ORG SUN GOD FESTIVAL 2014 A.S. COUNCIL LET’S FACE THE MUSIC Wristband Signups Will Occur Online Both Slates Charged for Campaign Violations BY gabriella fleischman NEWS EDITOR Multiple grievances were filed against the Let’s Act! slate, and one against Tritons Forward, for breaking campaigning rules on Tuesday, April 8 PHOTO BY ANDREW OH / GUARDIAN and Wednesday, April 9. Let’s Act! was found guilty of one of the accusations, Our most musically inclined two of the grievances were dropped Tritons will be performing and the rest have yet to be reviewed. The first two grievances were at the Battle of the Bands, filed by Triton’s Forward presidential taking place April 15 at The candidate Robby Boparai. One accused Loft. Read our guide on this the Let’s Act! slate of collaborating with Muir College Council slate year’s lineup. GLAD due to GLAD’s endorsement weekend, PAGE 6 of Let’s Act! However, according to Let’s Act! presidential candidate Kyle PHOTO BY DANIEL YUAN/GUARDIAN FILE Heiskala, Let’s Act! never asked for this A SILVER LINING endorsement. ELECTION SURPRISES UCSD is implementing an online registeration system for the Sun God Festival 2014 to shorten the long wait for wristbands. “The GLAD slate was in accordance council must inform voters Above, lines for wristbands extended from Thurgood Marhsall College to Earl Warren College prior to the festival in 2011. with their college council bylaws, and opinion, Page 4 they had the necessary approval,” Heiskala said. -

Gigs of My Steaming-Hot Member of Loving His Music, Mention in Your Letter

CATFISH & THE BOTTLEMEN Van McCann: “i’ve written 14 MARCH14 2015 20 new songs” “i’m just about BJORK BACK FROM clinging on to THE BRINK the wreckage” ENTER SHIKARI “ukiP are tAKING Pete US BACKWARDs” LAURA Doherty MARLING THE VERDICT ON HER NEW ALBUM OUT OF REHAB, INTO THE FUTURE ►THE ONLY INTERVIEW CLIVE BARKER CLIVE + Palma Violets Jungle Florence + The Machine Joe Strummer The Jesus And Mary Chain “It takes a man with real heart make to beauty out of the stuff that makes us weep” BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN 93NME15011142.pgs 09.03.2015 11:27 EmagineTablet Page HAMILTON POOL Home to spring-fed pools and lush green spaces, the Live Music Capital of the World® can give your next performance a truly spectacular setting. Book now at ba.com or through the British Airways app. The British Airways app is free to download for iPhone, Android and Windows phones. Live. Music. AustinTexas.org BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN 93NME15010146.pgs 27.02.2015 14:37 BAND LIST NEW MUSICAL EXPRESS | 14 MARCH 2015 Action Bronson 6 Kid Kapichi 25 Alabama Shakes 13 Laura Marling 42 The Amorphous Left & Right 23 REGULARS Androgynous 43 The Libertines 12 FEATURES Antony And The Lieutenant 44 Johnsons 12 Lightning Bolt 44 4 SOUNDING OFF Arcade Fire 13 Loaded 24 Bad Guys 23 Lonelady 45 6 ON REPEAT 26 Peter Doherty Bully 23 M83 6 Barli 23 The Maccabees 52 19 ANATOMY From his Thai rehab centre, Bilo talks Baxter Dury 15 Maid Of Ace 24 to Libs biographer Anthony Thornton Beach Baby 23 Major Lazer 6 OF AN ALBUM about Amy Winehouse, sobriety and Björk 36 Modest Mouse 45 Elastica -

A Guide to the Jody Fischer Collection of Willie Nelson

A Guide to the Jody Fischer Collection of Willie Nelson 1974-2003 [Bulk Dates 1974-1988] Collection 103 Descriptive Summary Creator: Fischer, Jody Title: Jody Fischer Collection of Willie Nelson Dates: 1974 – 2003 [Bulk Dates 1974-1988] Abstract: Jody Fischer’s collection of photographs, audio cassette tapes and VHS tapes relating to Willie Nelson are represented. The materials are arranged into the following series: Personal Papers, Ephemera, Posters, Photographs, Audio Cassette Tapes, Video Cassette Tapes, and Artifacts. Identification: Collection 103 Extent: 20 boxes plus oversize folders (13 linear feet) Language: English. Repository: Southwestern Writers Collection, Special Collections, Alkek Library, Texas State University-San Marcos Biographical Sketch Jody Fischer was born December 21, 1949. During the 1970’s she lived in New York City, and was active with the music scene. She was a bit of a musician and writer herself. According to a 1991 Texas Monthly article, she started following Willie Nelson in the early 1970’s helping wherever she could. When he purchased the Pedernales Country Club in 1979, she was hired on as his personal secretary. Her job was to schedule studio time for Willie and his musician friends, assist Lana Nelson with charitable work, and generally assist in managing the property. She also had a small part in his movie, Red-Headed Stranger, which was filmed on the property. When Willie Nelson began the Farm Aid movement, Jody took calls coming in from famers and their families, and is often quoted as being a compassionate listener. She was very close to the extended Nelson family, as well as involved in diverse causes such as Farm Aid and Native American civil rights.