The War on Drugs: Dream World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mary Lattimore & Jeff Zeigler

Mary Lattimore & Jeff Zeigler Music Inspired by Philippe Garrel’s Le Révélateur Thrill - 420 LP List $18.99 BOX LOT LP 25 *9037H-AECABg Vinyl is non-returnable GENRE : EXPERIMENTAL/SOUNDTRACK FILE UNDER: “L” Lattimore, Mary “Z” Zeigler, Jeff RELEASE DATE : July 22, 2016 Harpist Mary Lattimore and guitar/synthesizer player Jeff Zeigler NO EXPORT (JAPAN, S. AMERICA EXPORT OK) premiered their score for the 1968 French film Le Révélateur at the TRACK LISTING: 6. A Road renowned Ballroom Marfa’s annual silent film program in 2013. Although 1. The Glimmering Light 7. Hidden in a Cabinet created as an intentionally silent work, director Philippe Garrel endorsed 2. A Tunnel 8. Running Chased showing the film with every subsequent performance of the score. 3. A Forest 9. Stanislas 4. Laurent and Bernadette 10. The Revealer, Alone Lattimore and Zeigler’s score powerfully conveys isolation, despair and 5. Family Portrait 11. The Sparkling Sea awakening, amplifying sentiments portrayed in the film. Le révélateur, meaning the processor of images, in the film is the small boy who is given SALES POINTS voice through the rhythmic and inventive harp performance and through Lattimore and Zeigler present their score to French director emotive melodica lines, eerie synth and guitar. Together, the duo creates Philippe Garrel’s 1968 silent film Le Révélateur a soundscape that perfectly matches the film’s progression as it follows the boy’s journey from a family’s dysfunctional home life into a godless The duo of Mary Lattimore (harp) and Jeff Zeigler (guitar, post-apocalyptic landscape. Lattimore and Zeigler’s music becomes tense synthesizer, production) blend ancient classical traditions and rigid during scenes of desolation, switching only briefly to a soaring with modern improvisation and electronic performance major key during a moment of hope. -

The Independent / Suindependent.Com • February 2018 Alternative Rock Band from Salt Lake City Inspired by ‘90S Bands Like Nirvana, Soundgarden, and Foo Fighters

In print February 2018 - Vol. 22, #12 the 1st Friday FREE of each month Online at SUindependent.com PLEASE RECYCLE KANAB BALLOONS AND TUNES ROUNDUP SOARING TO GREATER HEIGHTS - See page 3 ALSO THIS ISSUE: RIRIE-WOODBURY DANCE COMPANY PREMIERS KAYENTA ART FOUNDAtion’s februarY ann carlson’s “elizabeth, the dance” in slc BEST EXPO EVER FEATURES SPRING BREAK STAYCATION, HELICOPTER RIDES, AND MORE SEASON: A MONTH OF VARIETY AND TALENT - See Page 4 - See Page 4 - See Page 5 ruffled some feathers in his short time at his publishing power in a way questionable the helm. Which brings me to the point of to some readers? Sure he does. But again, February 2018 Volume 22, Issue 12 this article here today. that’s the risk I as the publisher of The For many years, I’ve felt like the public Independent have always taken. and our readership has defined us. That’s It is often a difficult task for me to to say that we’ve been seen as a champion defend the musings of any writer or editor of many progressive causes to the point with the simple statement of “free speech,” where The Independent has been labeled but that truly is the defining characteristic “the liberal rag” by its detractors and “the of The Independent far more than anything only local publication I read” by many else. “But why?” many ask me. “How can progressives or those in the counterculture you publish and therefore promote ideas EDITORIAL ............................2 DOWNTOWN SECTION .......12 here in sunny southern Utah. In the last 22 that some find offensive, insensitive, biased, EVENTS ................................3 ALBUM REVIEWS ................14 years we’ve published content of virtually or angry?” Because ideas are simply that. -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Download Oxfordshire Music Scene 29 (3.7 Mb Pdf)

ISSUE 29 / JULY 2014 / FREE @omsmagazine INSIDE LEWIS WATSON WOOD & THE PUNT REVIEWED 2014 FESTIVAL GUIDE AUDIOSCOPE ECHO & THE BUNNYMEN AND MORE! GAZ COOMBES helicopters at glastonbury, new album and south park return NEWS news y v l Oxford Oxford is a new three day event for the city, happening i g O over the weekend of 26 to 28 September. The entertainment varies w e r over the weekend, exploring the four corners of the music, arts d n A and culture world. Friday’s theme is film/shows ( Grease sing-along and Alice In Wonderland ), Saturday, a more rock - ’n’roll vibe, with former Supergrass, now solo, mainstay, Gaz Coombes, returning to his old stomping ground, as well as a selection of names from the local and national leftfield like Tunng, Pixel Fix and Dance a la Plage with much more to be announced. Sunday is a free community event involving, so far, Dancin’ Oxford and Museum of Oxford and many more. t Community groups, businesses and sports clubs wishing to t a r P get involved should get in touch via the event website n a i r oxfordoxford.co.uk. Tickets are on sale now via the website SIMPLESIMPLMPLLEE d A with a discounted weekend ticket available to Oxford residents. MINDSMMININDS Audioscope have released two WITH MELANIEMELANMELANIE C albums of exclusives and rarities AND MARCMARC ALMONDALMOND which are available to download right now. Music for a Good Home 3 consists of 31 tracks from internationally known acts including: Amon Tobin, John Parish, Future of the Left, The Original Rabbit Foot Spasm Band, Oli from Stornoway’s Esben & the Witch, Thought Forms, Count Drachma (both pictured) and Aidan Skylarkin’ are all on Chrome Hoof, Tall Firs and many music bill for this year’s Cowley Carnival , now in its 14th year, more. -

Water on Mars Mary Bumblebee

DC533 Lolita Mercury Retrograde Rat Race Dead Again She Calms Me Down Face Down The Harrowing Wind Water On Mars LP/CD/CS Mary Bumblebee Release Date: March 19, 2013 PURLING HISS Water on Mars It takes balls to let Purling Hiss get in your face. Their records are a half-corroded, screaming roar of high-end gui- tars crushed together, obliterating vocals and even drums with their singular assault. Well, if you’ve got balls, get ready to swing ‘em. With Water On Mars, Purling Hiss have broken out of the basement, run through the bedroom and are out in the streets, blasting one of the great guitar albums in the past couple minutes. It’s a tumble of hits and ragers, sewing together nine new Purling Hiss celebration laments out of their usual patches of distortion, singing melodies and unexpected production hoohah — but this time the unexpected part is how the guitars gleam so precisely as they pile upon each other, how they work alongside of the rhythm section rather than avalanching it. And how the songs embody a variety of Hiss-teric moods, from the gutbusting bellow of “Lolita” and “Face Down” through the acoustic flatline of “Dead Again,” the aromatic slide guitars and piano within “She Calms Me Down,” the anthemish surge of “Rat Race” and the wailing march-jam, “Water On Mars.” Water On Mars is Purling Hiss’s first recording outside the fuzzy confines of Mike Polizze’s inner rock utopia, where the first three albums and EP were constructed in solitude with a home-recording setup. -

Feb. 13-19, 2014

FEB. 13-19, 2014 ------------------------------------------- Cover Story • Down the Line ------------------------------------------ Embassy Series Pairs Local Talent Iconic Rockin’:with Rock n’ Roll’s Greatest Acts By Steve Penhollow belts. Hell, I was 18 when I first joined the band. I’m 36 Heaven’s Gateway Drugs didn’t intend to pay tribute to now.” a deceased rock icon. Jason Bair says the mu- Things just turned out that way. sical chemistry he shares When the band was approached last year to take part in with his brother is uncanny. the eighth edition of Down the Line at the Embassy Theatre, “My brother and I don’t the almost instant consensus among its members was that even need to look at each they should perform the music of Velvet Underground at the other,” he says. “We know event. what each other is going to Before the band could get the go-ahead from the Em- do.” bassy’s front office, a period of “radio silence” ensued. “He’s really like an- Then Lou Reed, Velvet Underground’s guitarist and other appendage,” Eric principal songwriter, died last October. Bair concurs. “He knows “When Lou passed, we felt even more of an obligation what I’m thinking before [to play his music],” Derek Mauger, one of the band’s guitar- I’m even saying it when ists, says. it comes to music. So I’m Down the Line is a venerable event at a venerable venue crazy looking forward to that honors venerable musicians, but the local acts that par- practicing and rocking the ticipate are not cover bands per se and they always put their stage with him again. -

Deconstructing Los Angeles Or a Secret Fax from Magritte Regarding Postliterate Legal Reasoning: a Critique of Legal Education

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 26 1992 Deconstructing Los Angeles or a Secret Fax from Magritte Regarding Postliterate Legal Reasoning: A Critique of Legal Education C. Garrison Lepow Loyola University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Legal Education Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation C. G. Lepow, Deconstructing Los Angeles or a Secret Fax from Magritte Regarding Postliterate Legal Reasoning: A Critique of Legal Education, 26 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 69 (1992). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol26/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DECONSTRUCTING LOS ANGELES OR A SECRET FAX FROM MAGRITTE REGARDING POSTLITERATE LEGAL REASONING: A CRITIQUE OF LEGAL EDUCATION C. Garrison Lepow* Not only is it clear that most law students become impatient at some point during their three years of formal education, but it is clear also that how students learn the law is more the cause of their impatience than what they learn.' Moreover, others besides law students may be entitled to challenge the style of education that manufactures a lawyer-culture. If one assumes for the sake of argument that the intellectual processes of lawyers, and consequently their values, differ from those of their society, this fact does not explain the difference between legal thinking and regular thinking, or explain why there should not be harmony between the two. -

“All Politicians Are Crooks and Liars”

Blur EXCLUSIVE Alex James on Cameron, Damon & the next album 2 MAY 2015 2 MAY Is protest music dead? Noel Gallagher Enter Shikari Savages “All politicians are Matt Bellamy crooks and liars” The Horrors HAVE THEIR SAY The GEORGE W BUSH W GEORGE Prodigy + Speedy Ortiz STILL STARTING FIRES A$AP Rocky Django Django “They misunderestimated me” David Byrne THE PAST, PRESENT & FUTURE OF MUSIC Palma Violets 2 MAY 2015 | £2.50 US$8.50 | ES€3.90 | CN$6.99 # "% # %$ % & "" " "$ % %"&# " # " %% " "& ### " "& "$# " " % & " " &# ! " % & "% % BAND LIST NEW MUSICAL EXPRESS | 2 MAY 2015 Anna B Savage 23 Matthew E White 51 A$AP Rocky 10 Mogwai 35 Best Coast 43 Muse 33 REGULARS The Big Moon 22 Naked 23 FEATURES Black Rebel Motorcycle Nicky Blitz 24 Club 17 Noel Gallagher 33 4 Blanck Mass 44 Oasis 13 SOUNDING OFF Blur 36 Paddy Hanna 25 6 26 Breeze 25 Palma Violets 34, 42 ON REPEAT The Prodigy Brian Wilson 43 Patrick Watson 43 Braintree’s baddest give us both The Britanys 24 Passion Pit 43 16 IN THE STUDIO Broadbay 23 Pink Teens 24 Radkey barrels on politics, heritage acts and Caribou 33 The Prodigy 26 the terrible state of modern dance Carl Barât & The Jackals 48 Radkey 16 17 ANATOMY music. Oh, and eco light bulbs… Chastity Belt 45 Refused 6, 13 Coneheads 23 Remi Kabaka 15 David Byrne 12 Ride 21 OF AN ALBUM De La Soul 7 Rihanna 6 Black Rebel Motorcycle Club 32 Protest music Django Django 15, 44 Rolo Tomassi 6 – ‘BRMC’ Drenge 33 Rozi Plain 24 On the eve of the general election, we Du Blonde 35 Run The Jewels 6 -

Dave Hartley on How to Balance Your Personal Project with the One That Pays the Bills

October 30, 2017 - Philadelphia’s Dave Hartley is best known for his supporting role as the bassist in The War on Drugs, the popular heartland rock band that just released its fourth album, A Deeper Understanding. Aside from the band’s founder, Adam Granduciel, Hartley is the only member to appear on every album. But in his spare time, Hartley makes symphonic pop as Nightlands, a group he concedes may sell more tickets and records if it sounded more like The War on Drugs. But for Hartley, who released his fourth Nightlands album, I Can Feel the Night Around Me, in May, compensation is the least important reason for pursuing his own project. As told to Grayson Haver Currin, 2256 words. Tags: Music, Inspiration, Beginnings, Process, First attempts, Multi-tasking, Success. Dave Hartley on how to balance your personal project with the one that pays the bills You released the first album from your own project, Nightlands, two years after the first album by The War on Drugs. Did playing bass with that band inspire you to try something on your own? The story of my involvement in The War on Drugs is the story of musical maturation. I met Adam Granduciel when I was 25 or so. We both worked a shit job together at this property management company. We’d moved to Philadelphia around the same time for the same reasons. A lot of people leave home, go to college, and want to go somewhere new. You don’t realize at the time that you’re setting your life on a path, when you think you’re just drifting. -

San Miguel Primavera Sound

SAN MIGUEL PRIMAVERA SOUND CARTELL 2012 PARC DEL FÒRUM PROGRAMACIÓ COMPLEMENTÀRIA san MIGUEL PRIMAVERA A LA CIUTAT PRIMAVERAPRO ORGANITZACIÓ I PARTNERS TIQUETS I PUNTS DE VENDA CRONOGRAMA D’activitats PLÀNOL parc DEL fòrum adreces recintes CAMPANYA GRÀFICA CITES DE PREMSA HISTÒRIA ANNEX: Biografies D’artistes CONTACTE SAN MIGUEL PRIMAVERA SOUND Des dels seus inicis el festival ha centrat els seus esforços en oferir noves propostes musicals de l’àmbit independent juntament amb artistes de contrastada trajectòria i de qualsevol estil o gènere, buscant primordialment la qualitat i apostant essencialment pel pop, el rock i les tendències més underground de la música electrònica i de ball. El festival ha comptat al llarg de la seva trajectòria amb propostes dels més diversos colors i estils. Així ho demostren els artistes que durant aquests deu anys han desfilat pels seus escenaris: de Pixies a Aphex Twin, passant per Neil Young,Sonic Youth, Portishead, Pet Shop Boys, Pavement, Yo la tengo, Lou Reed, My Bloody Valentine, El-P, Pulp, Patti Smith, James Blake, Arcade Fire, Public Enemy, Grinderman, Television, Devo, Enrique Morente, The White Stripes, Wil- co, Tindersticks, PJ Harvey, Shellac, Dinosaur Jr., New Order, Surfin’ Bichos, Fuck Buttons, Melvins, The National, Psychic TV o Spiritualized, entre molts d’altres. REPERCUSSIÓ D’EDICIONS ANTERIORS Any rere any, el festival San Miguel Primavera Sound ha anat incrementant tant l’assistència de públic com la re- percussió als principals mitjans de premsa, ràdio i televisió. Si la primera edició va tancar amb una assistència de 8.000 persones, la del 2002 va arribar a 18.000 i la de 2003 va reunir entre els seus espais a més de 24.000 persones, l’assistència de 40.000 persones a l’any 2004 va significar un punt i apart i el festival va abandonar el Poble Espanyol. -

Recording Artist Recording Title Price 2Pac Thug Life

Recording Artist Recording Title Price 2pac Thug Life - Vol 1 12" 25th Anniverary 20.99 2pac Me Against The World 12" - 2020 Reissue 24.99 3108 3108 12" 9.99 65daysofstatic Replicr 2019 12" 20.99 A Tribe Called Quest We Got It From Here Thank You 4 Your Service 12" 20.99 A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Travels And The Paths Of Rhythm 12" Reissue 26.99 Abba Live At Wembley Arena 12" - Half Speed Master 3 Lp 32.99 Abba Gold 12" 22.99 Abba Abba - The Album 12" 12.99 AC/DC Highway To Hell 12" 20.99 Ace Frehley Spaceman - 12" 29.99 Acid Mothers Temple Minstrel In The Galaxy 12" 21.99 Adele 25 12" 16.99 Adele 21 12" 16.99 Adele 19- 12" 16.99 Agnes Obel Myopia 12" 21.99 Ags Connolly How About Now 12" 9.99 Air Moon Safari 12" 15.99 Alan Marks Erik Satie - Vexations 12" 19.99 Aldous Harding Party 12" 16.99 Alec Cheer Night Kaleidoscope Ost 12" 14.99 Alex Banks Beneath The Surface 12" 19.99 Alex Lahey The Best Of Luck Club 12" White Vinyl 19.99 Algiers There Is No Year 12" Dinked Edition 26.99 Ali Farka Toure With Ry Cooder Talking Timbuktu 12" 24.99 Alice Coltrane The Ecstatic Music Of... 12" 28.99 Alice Cooper Greatest Hits 12" 16.99 Allah Las Lahs 12" Dinked Edition 19.99 Allah Las Lahs 12" 18.99 Alloy Orchestra Man With A Movie Camera- Live At Third Man Records 12" 12.99 Alt-j An Awesome Wave 12" 16.99 Amazones D'afrique Amazones Power 12" 24.99 American Aquarium Lamentations 12" Colour Vinyl 16.99 Amy Winehouse Frank 12" 19.99 Amy Winehouse Back To Black - 12" 12.99 Anchorsong Cohesion 12" 12.99 Anderson Paak Malibu 12" 21.99 Andrew Bird My Finest Work 12" 22.99 Andrew Combs Worried Man 12" White Vinyl 16.99 Andrew Combs Ideal Man 12" Colour Vinyl 16.99 Andrew W.k I Get Wet 12" 38.99 Angel Olsen All Mirrors 12" Clear Vinyl 22.99 Angelo Badalamenti Twin Peaks - Ost 12" - Ltd Green 20.99 Ann Peebles Greatest Hits 12" 15.99 Anna Calvi Hunted 12" - Ltd Red 24.99 Anna St. -

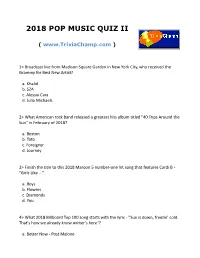

2018 Pop Music Quiz Ii

2018 POP MUSIC QUIZ II ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> Broadcast live from Madison Square Garden in New York City, who received the Grammy for Best New Artist? a. Khalid b. SZA c. Alessia Cara d. Julia Michaels 2> What American rock band released a greatest hits album titled "40 Trips Around the Sun" in February of 2018? a. Boston b. Toto c. Foreigner d. Journey 3> Finish the title to this 2018 Maroon 5 number-one hit song that features Cardi B - "Girls Like ...". a. Boys b. Flowers c. Diamonds d. You 4> What 2018 Billboard Top 100 song starts with the lyric - "Sun is down, freezin' cold. That's how we already know winter's here"? a. Better Now - Post Malone b. Nice For What - Drake c. Youngblood - 5 Seconds of Summer d. Sicko Mode - Travis Scott 5> Which American rapper had Billboard hits with the songs "Kamikaze", "The Ringer" and "Fall" in 2018? a. Lil Wayne b. Eminem c. Tupac Shakur d. 50 Cent 6> On the Billboard Hot Rock Songs chart in 2018, finish the title to this "Greta Van Fleet" hit song - "When the ...". a. Moneys Gone b. Sun Comes Down c. Levee Breaks d. Curtain Falls 7> Known as the "Queen of Soul", what artist died after a long battle with pancreatic cancer in August of 2018? a. Whitney Houston b. Aretha Franklin c. Patti LaBelle d. Tina Turner 8> Released on her debut studio album "Expectations", which American singer had a hit with the song "I'm a Mess"? a. Rita Ora b. Bebe Rexha c.