Tayinat's Building XVI: the Religious Dimensions and Significance of A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Introduction to the Egypt-Mitanni Affairs in the Amarna Letters

estudos internacionais • Belo Horizonte, ISSN 2317-773X, v.6 n.2 (2018), p.65 - 78 The ancient Near East in contact: an introduction to the Egypt-Mitanni affairs in the Amarna Letters O Oriente Próximo em contato: uma introdução às relações Egito-Mitani nas Cartas de Amarna DOI: 10.5752/P.2317-773X.2017v6.n2.p65 1 Priscila Scoville 1. PhD candidate at Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. Representative of the Association for Students of Egyptology (ASE). Recebido em 30 de setembro de 2016 ORCID: 0000-0003-1193-1321 Aceito em 04 de maio de 2018 Abstract The aim of this paper is to provide an introduction to the study of diplomatic relations in the Ancient Near East, more specifically during the so-called Amarna Age. A field so commonly dismissed among scholars of International Relations, ancient diplomacy can be a fertile ground to understand the birth of pre-modern political contacts and extra-societal issues. In order to explore this topic, I will make use of the Amarna Letters, a collection of tablets, found in the modern city of Tell el-Amarna, that represents one of the first complex diplomatic systems in the world (a system that is subsequent to the Ages of Ebla and Mari). I will also discuss the context of the relationships established and the affairs between the kingdoms of Egypt and Mitanni, using as a case study to demonstrate how the rhetoric and the political arguments were present – and fundamental – to the understanding of diplomacy in Antiquity. Keywords: Amarna Letters, Mitanni, Egypt, Near East Resumo O objetivo deste trabalho é apresentar uma introdução ao estudo das relações diplomáticas no antigo Oriente Próximo, mais especificamente durante a chamada Era de Amarna. -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

Hanigalbat and the Land Hani

Arnhem (nl) 2015 – 3 Anatolia in the bronze age. © Joost Blasweiler student Leiden University - [email protected] Hanigal9bat and the land Hana. From the annals of Hattusili I we know that in his 3rd year the Hurrian enemy attacked his kingdom. Thanks to the text of Hattusili I (“ruler of Kussara and (who) reign the city of Hattusa”) we can be certain that c. 60 years after the abandonment of the city of Kanesh, Hurrian armies extensively entered the kingdom of Hatti. Remarkable is that Hattusili mentioned that it was not a king or a kingdom who had attacked, but had used an expression “the Hurrian enemy”. Which might point that formerly attacks, raids or wars with Hurrians armies were known by Hattusili king of Kussara. And therefore the threatening expression had arisen in Hittite: “the Hurrian enemy”. Translation of Gary Beckman 2008, The Ancient Near East, editor Mark W. Chavalas, 220. The cuneiform texts of the annal are bilingual: Babylonian and Nesili (Hittite). Note: 16. Babylonian text: ‘the enemy from Ḫanikalbat entered my land’. The Babylonian text of the bilingual is more specific: “the enemy of Ḫanigal9 bat”. Therefore the scholar N.B. Jankowska1 thought that apparently the Hurrian kingdom Hanigalbat had existed probably from an earlier date before the reign of Hattusili i.e. before c. 1650 BC. Normally with the term Mittani one is pointing to the mighty Hurrian kingdom of the 15th century BC 2. Ignace J. Gelb reported 3 on “the dragomans of the Habigalbatian soldiers/workers” in an Old Babylonian tablet of Amisaduqa, who was a contemporary with Hattusili I. -

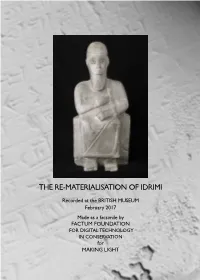

The Re-Materialisation of Idrimi

THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI Recorded at the BRITISH MUSEUM February 2017 Made as a facsimile by FACTUM FOUNDATION FOR DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY IN CONSERVATION for MAKING LIGHT THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI SEPTEMBER 2017 The Statue of Idrimi photographed during the recording session at the British Museum in February 2017 2 THE STATUE OF IDRIMI The statue of Idrimi, carved in magnesite with inlaid glass eyes, too delicate and rare to ever travel, has been kept in a glass case at the British Museum since its discovery by the British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley in 1939. It was ex- cavated in what is now part of Turkey at Tell Atchana, the remains of the ancient Syrian city-state of Alalakh. From the autobiographical cuneiform inscription on the statue, we know that Idrimi was King of Alalakh in the 15th century BC. A son of the royal house of Aleppo, Idrimi fled his home as a youth with his family and after spending some years in Emar and then amongst the tribes in Canaan, became King of Alalakh. At the time of inscribing the statue, Idrimi had ruled Alalakh for thirty years. The inscription is considered one of the most interesting cuneiform texts ever found, both because of its autobiographical nature and because of the rarity of the script. It describes Idrimi’s early life and escape from Aleppo into the steppes, his accession to power, as well as the military and social achievements of his reign. It places a curse on any person who moves the statue, erases or in any way alters the words, but the inscription ends by commending the scribe to the gods and with a blessing to those who would look at the statue and read the words: “I was king for 30 years. -

Feasting in Homeric Epic 303

HESPERIA 73 (2004) FEASTING IN Pages 301-337 HOMERIC EPIC ABSTRACT Feasting plays a centralrole in the Homeric epics.The elements of Homeric feasting-values, practices, vocabulary,and equipment-offer interesting comparisonsto the archaeologicalrecord. These comparisonsallow us to de- tect the possible contribution of different chronologicalperiods to what ap- pearsto be a cumulative,composite picture of around700 B.c.Homeric drink- ing practicesare of particularinterest in relation to the history of drinkingin the Aegean. By analyzing social and ideological attitudes to drinking in the epics in light of the archaeologicalrecord, we gain insight into both the pre- history of the epics and the prehistoryof drinkingitself. THE HOMERIC FEAST There is an impressive amount of what may generally be understood as feasting in the Homeric epics.' Feasting appears as arguably the single most frequent activity in the Odysseyand, apart from fighting, also in the Iliad. It is clearly not only an activity of Homeric heroes, but also one that helps demonstrate that they are indeed heroes. Thus, it seems, they are shown doing it at every opportunity,to the extent that much sense of real- ism is sometimes lost-just as a small child will invariablypicture a king wearing a crown, no matter how unsuitable the circumstances. In Iliad 9, for instance, Odysseus participates in two full-scale feasts in quick suc- cession in the course of a single night: first in Agamemnon's shelter (II. 1. thanks to John Bennet, My 9.89-92), and almost immediately afterward in the shelter of Achilles Peter Haarer,and Andrew Sherrattfor Later in the same on their return from their coming to my rescueon variouspoints (9.199-222). -

Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign

oi.uchicago.edu STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION * NO.42 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Thomas A. Holland * Editor with the assistance of Thomas G. Urban oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber THE ROAD TO KADESH A HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION OF THE BATTLE RELIEFS OF KING SETY I AT KARNAK SECOND EDITION REVISED WILLIAM J. MURNANE THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION . NO.42 CHICAGO * ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 90-63725 ISBN: 0-918986-67-2 ISSN: 0081-7554 The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 1985, 1990 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1990. Printed in the United States of America. oi.uchicago.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS List of M aps ................................ ................................. ................................. vi Preface to the Second Edition ................................................................................................. vii Preface to the First Edition ................................................................................................. ix List of Bibliographic Abbreviations ..................................... ....................... xi Chapter 1. Egypt's Relations with Hatti From the Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign ...................................................................... ......................... 1 The Clash of Empires -

Sales 2015 Políticas E Culturas No Antigo Egipto.Pdf

COLECÇÃO COMPENDIUM Chiado Editora chiadoeditora.com Um livro vai para além de um objecto. É um encontro entre duas pessoas através da pa- lavra escrita. É esse encontro entre autores e leitores que a Chiado Editora procura todos os dias, trabalhando cada livro com a dedicação de uma obra única e derradeira, seguindo a máxima pessoana “põe quanto és no mínimo que fazes”. Queremos que este livro seja um desafio para si. O nosso desafio é merecer que este livro faça parte da sua vida. www.chiadoeditora.com Portugal | Brasil | Angola | Cabo Verde Avenida da Liberdade, N.º 166, 1.º Andar 1250-166 Lisboa, Portugal Conjunto Nacional, cj. 903, Avenida Paulista 2073, Edifício Horsa 1, CEP 01311-300 São Paulo, Brasil © 2015, José das Candeias Sales e Chiado Editora E-mail: [email protected] Título: Política(s) e Cultura(s) no Antigo Egipto Editor: Rita Costa Composição gráfica: Ricardo Heleno – Departamento Gráfico Capa: Ana Curro Foto da capa: O templo funerário de Hatchepsut, em Deir el-Bahari, Tebas ocidental. Foto do Autor Revisão: José das Candeias Sales Impressão e acabamento: Chiado Print 1.ª edição: Setembro, 2015 ISBN: 978-989-51-3835-7 Depósito Legal n.º 389152/15 JOSÉ DAS CANDEIAS SALES POLÍTICA(S) E CULTURA(S) NO ANTIGO EGIPTO Chiado Editora Portugal | Brasil | Angola | Cabo Verde ÍNDICE GERAL APRESENTAÇÃO 7 I PARTE Legitimação política e ideológica no Egipto antigo – discurso e práticas 11 1. Concepção e percepção de tempo e de temporalidade no Egipto antigo 17 2. As fórmulas protocolares egípcias ou formas e possibilidades do discurso de legitimação no antigo Egipto 49 3. -

Ugaritic Seal Metamorphoses As a Reflection of the Hittite Administration and the Egyptian Influence in the Late Bronze Age in Western Syria

UGARITIC SEAL METAMORPHOSES AS A REFLECTION OF THE HITTITE ADMINISTRATION AND THE EGYPTIAN INFLUENCE IN THE LATE BRONZE AGE IN WESTERN SYRIA The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by B. R. KABATIAROVA In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY OF ART BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA June 2006 To my family and Őzge I certify that I have read this thesis and that it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Archaeology and History of Art. -------------------------------------------- Dr. Marie-Henriette Gates Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and that it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Archaeology and History of Art. -------------------------------------------- Dr. Jacques Morin Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and that it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Archaeology and History of Art. -------------------------------------------- Dr. Geoffrey Summers Examining Committee Member Approval of the Institute of Economics and Social Sciences ------------------------------------------- Dr. Erdal Erel Director ABSTRACT UGARITIC SEAL METAMORPHOSES AS A REFLECTION OF THE HITTITE ADMINISTRATION AND THE EGYPTIAN INFLUENCE IN THE LATE BRONZE AGE IN WESTERN SYRIA Kabatiarova, B.R. M.A., Department of Archaeology and History of Art Supervisor: Doc. Dr. Marie-Henriette Gates June 2006 This study explores the ways in which Hittite political control of Northern Syria in the LBA influenced and modified Ugaritic glyptic and methods of sealing documents. -

2008: 137-8, Pl. 32), Who Assigned Gateway XII to the First Building

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 29 November 2019 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Osborne, J. and Harrison, T. and Batiuk, S. and Welton, L. and Dessel, J.P. and Denel, E. and Demirci, O.¤ (2019) 'Urban built environments of the early 1st millennium BCE : results of the Tayinat Archaeological Project, 2004-2012.', Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research., 382 . pp. 261-312. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1086/705728 Publisher's copyright statement: c 2019 by the American Schools of Oriental Research. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Manuscript Click here to access/download;Manuscript;BASOR_Master_revised.docx URBAN BUILT ENVIRONMENTS OF THE EARLY FIRST MILLENNIUM BCE: RESULTS OF THE TAYINAT ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT, 2004-2012 ABSTRACT The archaeological site of Tell Tayinat in the province of Hatay in southern Turkey was the principal regional center in the Amuq Plain and North Orontes Valley during the Early Bronze and Iron Ages. -

New Horizons in the Study of Ancient Syria

OFFPRINT FROM Volume Twenty-five NEW HORIZONS IN THE STUDY OF ANCIENT SYRIA Mark W. Chavalas John L. Hayes editors ml"ITfE ADMINISTRATION IN SYRIA IN THE LIGHT OF THE TEXTS FROM UATTUSA, UGARIT AND EMAR Gary M. Beckman Although the Hittite state of the Late Bronze Age always had its roots in central Anatolia,1 it continually sought to expand its hegemony toward the southeast into Syria, where military campaigns would bring it booty in precious metals and other goods available at home only in limited quantities, and where domination would assure the constant flow of such wealth in the fonn of tribute and imposts on the active trade of this crossroads between Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Aegean. Already in the 'seventeenth century, the Hittite kings ~attu§ili I and his adopted son and successor Mur§ili I conquered much of this area, breaking the power of the "Great Kingdom" of ~alab and even reaching distant Babylon, where the dynasty of ~ammurapi was brought to an end by Hittite attack. However, the Hittites were unable to consolidate their dominion over northern Syria and were soon forced back to the north by Hurrian princes, who were active even in eastern Anatolia.2 Practically nothing can be said concerning Hittite administration of Syria in this period, known to Hittitologists as the Old Kingdom. During the following Middle Kingdom (late sixteenth-early fourteenth centuries), Hittite power was largely confined to Anatolia, while northern Syria came under the sway 1 During the past quarter century research in Hittite studies bas proceeded at such a pace that there currently exists no adequate monographic account ofAnatolian history and culture of the second millennium. -

Shifting Networks and Community Identity at Tell Tayinat in the Iron I (Ca

Shifting Networks and Community Identity at Tell Tayinat in the Iron I (ca. 12th to Mid 10th Century B.C.E.) , , , , , , , , Open Access on AJA Online Includes Supplementary Content on AJA Online The end of the 13th and beginning of the 12th centuries B.C.E. witnessed the demise of the great territorial states of the Bronze Age and, with them, the collapse of the ex- tensive interregional trade networks that fueled their wealth and power. The period that follows has historically been characterized as an era of cultural devolution marked by profound social and political disruption. This report presents the preliminary results of the Tayinat Archaeological Project (TAP) investigations of Iron I (ca. 12th to mid 10th century B.C.E.) contexts at Tell Tayinat, which would emerge from this putative Dark Age as Kunulua, royal capital of the Neo-Hittite kingdom of Palastin/Patina/Unqi. In contrast to the prevailing view, the results of the TAP investigations at Early Iron Age Tayinat reveal an affluent community actively interacting with a wide spectrum of re- gions throughout the eastern Mediterranean. The evidence from Tayinat also highlights the distinctively local, regional character of its cultural development and the need for a more nuanced treatment of the considerable regional variability evident in the eastern Mediterranean during this formative period, a treatment that recognizes the diversity of relational networks, communities, and cultural identities being forged in the generation of a new social and economic order.1 -

Generation Count in Hittite Chronology 73

071_080.qxd 13.02.2004 11:54 Seite 71 G E N E R A T I O N C O U N T I N H I T T I T E C H R O N O L O G Y Gernot Wilhelm* In studies on Ancient Near Eastern chronology of three participants who voted for the high Hittite history has often been considered a corner- chronology without hesitation (ÅSTRÖM 1989: 76). stone of a long chronology. In his grandiose but – At a colloquium organized by advocates of an as we now see – futile attempt to denounce the ultra-low chronology at Ghent, another hittitolo- Assyrian Kinglist as a historically unreliable source gist, B ECKMAN 2000: 25, deviated from the main- for the Assyrian history of the first half of the 2nd stream by declaring that from his viewpoint, “the millennium B.C., L ANDSBERGER 1954: 50 only Middle Chronology best fits the evidence, although briefly commented on Hittite history. 1 A. Goetze, the High Chronology would also be possible”. however, who at that time had already repeatedly Those hittitologists who adhered to the low defended a long chronology against the claims of chronology (which means, sack of Babylon by the followers of the short chronology (GOETZE Mursili I: 1531) had to solve the problem of 1951, 1952), filled the gap and supported Lands- squeezing all the kings attested between Mursili I berger’s plea for a long chronology, though not as and Suppiluliuma I into appr. 150 years, provided excessively long as Landsberger considered to be that there was agreement on Suppiluliuma’s likely.