Hanigalbat and the Land Hani

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Orontids of Armenia by Cyril Toumanoff

The Orontids of Armenia by Cyril Toumanoff This study appears as part III of Toumanoff's Studies in Christian Caucasian History (Georgetown, 1963), pp. 277-354. An earlier version appeared in the journal Le Muséon 72(1959), pp. 1-36 and 73(1960), pp. 73-106. The Orontids of Armenia Bibliography, pp. 501-523 Maps appear as an attachment to the present document. This material is presented solely for non-commercial educational/research purposes. I 1. The genesis of the Armenian nation has been examined in an earlier Study.1 Its nucleus, succeeding to the role of the Yannic nucleus ot Urartu, was the 'proto-Armenian,T Hayasa-Phrygian, people-state,2 which at first oc- cupied only a small section of the former Urartian, or subsequent Armenian, territory. And it was, precisely, of the expansion of this people-state over that territory, and of its blending with the remaining Urartians and other proto- Caucasians that the Armenian nation was born. That expansion proceeded from the earliest proto-Armenian settlement in the basin of the Arsanias (East- ern Euphrates) up the Euphrates, to the valley of the upper Tigris, and espe- cially to that of the Araxes, which is the central Armenian plain.3 This expand- ing proto-Armenian nucleus formed a separate satrapy in the Iranian empire, while the rest of the inhabitants of the Armenian Plateau, both the remaining Urartians and other proto-Caucasians, were included in several other satrapies.* Between Herodotus's day and the year 401, when the Ten Thousand passed through it, the land of the proto-Armenians had become so enlarged as to form, in addition to the Satrapy of Armenia, also the trans-Euphratensian vice-Sa- trapy of West Armenia.5 This division subsisted in the Hellenistic phase, as that between Greater Armenia and Lesser Armenia. -

<Article-Title> <Xref Ref-Type="Transliteration" Rid="Trans6

Nairi e Ir(u)aṭri. Contributo alla storia della Formazione del regno di Urartu by Mirjo Salvini Review by: Giorgio Buccellati Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 92, No. 2 (Apr. - Jun., 1972), pp. 297-298 Published by: American Oriental Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/600663 . Accessed: 03/02/2012 16:42 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Oriental Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the American Oriental Society. http://www.jstor.org Reviews of Books 297 The main thesis, outlined at the beginning of this disbelief that one realizes that Tuspa, the capital of review, is contained in chapter II (pp. 55-70). Urartu on the shores of Lake Van, is only about 130 The following three chapters develop certain corol- miles as the crow flies from Nineveh, i.e. about half the laries implicit in the main thesis, the most important distance between Nineveh and Babylon. Urartu was, in being in chapter III (pp. 71-93). Here the author analyzes other words, by far the closest to Assyria of all the the relationship between the prepositive article and the powerful foreign countries. -

Nochmals Zur Geschichte Und Lage Der Hethitischen Stadt Ankuwa

STUDI MICENEI ED EGEO-ANATOLICI FASCICOLO XXIV IN MEMORIA DI PIERO MERIGGI (1899-1982) ff ROMA, EDIZIONI DELL'ATENEO 1984 INDICE DEL FASCICOLO XXIV Ricordo di Piero Meriggi Pdg> 3 Ncar Eastern Trade and the Emergencc of Interaction with Grete in the Third Millennium B.C., by HORST KLENGEL » 7 Nilabsinu und der altorientalische Name des Teil Brak, von KARLHEINZ KESSLER » 21 Zu den hurritischen Personennamen aus Kär-Tukulti-Ninurta, von HELMUT FREYDANK und MIRJO SALVINI » 33 Nasalization im Anatolischen, von ONOFRIO CARRUBA » 57 Studien über das hethitische Kriegswesen II: Verba delendi har- ninkr/harganu- «vernichten, zugrunde richten», von AHMET UNAL » 71 Nochmals zur Geschichte und Lage der hethitischen Stadt Ankuwa, von AHMET ÜNAL » 87 II ruolo delle «truppe» UKU.U§ nell'organizzazione militare ittita, di SUSANNA Rosi » 109 II LUALAN.ZÜ come «mimo» e come «attore» nei testi ittiti, di STEFANO DE MARTINO » 131 Ittito:L^PFIN^^SAR)=§U.KI§SAR((ortica (?))>, di MIRELLA VITO ... » 149 Scribi hurriti a Bogazköy: una verifica prosopografica, di LORENZA M. MASCHERONI » 151 Die hethitisch-hurritischen Rituale des (h)isuwa-F estes, von MIRJO SALVINI und ILSE WEGNER » 175 Eine Anrufung an den Gott Tessup von Halab in hurritischer Sprache, von H.-J. THIEL! und ILSE WEGNER » 187 Die Inschrift auf der Statue der Tatu-Hepa und die hurritischen deikti• schen Pronomina, von GERNOT WILHELM » 215 Hurritisch nari(ya) «fünf», von GERNOT WILHELM » 223 The Outline of Anatolian Onomastics, by ARAM V. KHOSSIAN » 225 Le pays Istikuniu d'une inscription cuneiforme -

INITIATIVE for CUNEIFORM ENCODING PROPOSAL November 1, 2003

INITIATIVE FOR CUNEIFORM ENCODING PROPOSAL November 1, 2003 [IMPORTANT NOTE: Due to the pressures of time and other considerations this is one of two proposals submitted to the Unicode Technical Committee by the Initiative for Cuneiform Encoding prior to the UTC meeting at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Nov. 4-7, 2003. This is NOT, however, intended as two competing proposals; it is merely insurance to make sure all exigencies are covered before the ICE proposal presentation at UTC. We intend to present a single proposal.] We find ourselves at an historic crux in the history of writing. From our vantage point we can look backwards 5600 years to the beginnings of the world's first writing, cuneiform, and we can look forward into a future where that heritage will be preserved. International computer standards make it possible. Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform is the world's oldest and longest used writing system. The earliest texts appear in Mesopotamia around 3600 BC and the last native cuneiform texts were written around 75 AD. The ancient scribes pressed the ends of their styluses into damp clay in order to write the approximately 800 different syllabic, logographic, or taxographic signs of this complex, poly-valent script. The clay tablets were sun-dried or baked by fire and were thus preserved in the sands of the Near East for millennia. Since the decipherment of Babylonian cuneiform some 150 years ago museums have accumulated perhaps 300,000 tablets written in most of the major languages of the Ancient Near East - Sumerian, Akkadian (Babylonian and Assyrian), Eblaite, Hittite, Hurrian, and Elamite. -

For the Hittite “Royal Guard” During the Old Kingdom: Observations on Elite Military Units and Their Possible Warfare Applications

Athens Journal of Mediterranean Studies - Volume 7, Issue 3, July 2021 – Pages 171-186 The “Protocols” for the Hittite “Royal Guard” during the Old Kingdom: Observations on Elite Military Units and their Possible Warfare Applications By Eduardo Ferreira* In this article, we intend to analyse the importance and modus operandi of a military unit (generally known as “Royal Guard”) whose function was, among other things, the protection of the Hattuša-based Hittite kings. For this essay, we will be mainly using two Hittite textual sources known as “instructions” or “protocols”. We aim to find a connection between these guards and their function regarding the protection of the royal palace as well as their military enlistment in that elite unit. The period to be covered in this analysis comes directly from the choice of sources: the Hittite Old Kingdom, confined between the chronological beacons of the 17th, 16th and 15th centuries BC. With this analysis, we intend to provide some relevant data that may contribute to a better understanding of these elite military units, particularly in regards to their probable warfare functions. Were they used in battle? How were they armed? What was their tactical importance in combat? How was the recruitment done? How were the units formed? These will be some questions that we will try to answer throughout this article. Keywords: guard, palace, command, warfare, infantry Introduction The Hittites were an Indo-European people that arrived in Anatolia through the Caucasus from Eurasia between 2000 and 1900 BC (Haywood 2005, Bryce 2005). On their Indo-European journey to the west, they also brought horses (Raulwing 2000, Renfrew 1990, Joseph and Fritz 2017/2018). -

Sumerian Lexicon, Version 3.0 1 A

Sumerian Lexicon Version 3.0 by John A. Halloran The following lexicon contains 1,255 Sumerian logogram words and 2,511 Sumerian compound words. A logogram is a reading of a cuneiform sign which represents a word in the spoken language. Sumerian scribes invented the practice of writing in cuneiform on clay tablets sometime around 3400 B.C. in the Uruk/Warka region of southern Iraq. The language that they spoke, Sumerian, is known to us through a large body of texts and through bilingual cuneiform dictionaries of Sumerian and Akkadian, the language of their Semitic successors, to which Sumerian is not related. These bilingual dictionaries date from the Old Babylonian period (1800-1600 B.C.), by which time Sumerian had ceased to be spoken, except by the scribes. The earliest and most important words in Sumerian had their own cuneiform signs, whose origins were pictographic, making an initial repertoire of about a thousand signs or logograms. Beyond these words, two-thirds of this lexicon now consists of words that are transparent compounds of separate logogram words. I have greatly expanded the section containing compounds in this version, but I know that many more compound words could be added. Many cuneiform signs can be pronounced in more than one way and often two or more signs share the same pronunciation, in which case it is necessary to indicate in the transliteration which cuneiform sign is meant; Assyriologists have developed a system whereby the second homophone is marked by an acute accent (´), the third homophone by a grave accent (`), and the remainder by subscript numerals. -

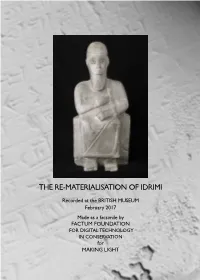

The Re-Materialisation of Idrimi

THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI Recorded at the BRITISH MUSEUM February 2017 Made as a facsimile by FACTUM FOUNDATION FOR DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY IN CONSERVATION for MAKING LIGHT THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI SEPTEMBER 2017 The Statue of Idrimi photographed during the recording session at the British Museum in February 2017 2 THE STATUE OF IDRIMI The statue of Idrimi, carved in magnesite with inlaid glass eyes, too delicate and rare to ever travel, has been kept in a glass case at the British Museum since its discovery by the British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley in 1939. It was ex- cavated in what is now part of Turkey at Tell Atchana, the remains of the ancient Syrian city-state of Alalakh. From the autobiographical cuneiform inscription on the statue, we know that Idrimi was King of Alalakh in the 15th century BC. A son of the royal house of Aleppo, Idrimi fled his home as a youth with his family and after spending some years in Emar and then amongst the tribes in Canaan, became King of Alalakh. At the time of inscribing the statue, Idrimi had ruled Alalakh for thirty years. The inscription is considered one of the most interesting cuneiform texts ever found, both because of its autobiographical nature and because of the rarity of the script. It describes Idrimi’s early life and escape from Aleppo into the steppes, his accession to power, as well as the military and social achievements of his reign. It places a curse on any person who moves the statue, erases or in any way alters the words, but the inscription ends by commending the scribe to the gods and with a blessing to those who would look at the statue and read the words: “I was king for 30 years. -

Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign

oi.uchicago.edu STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION * NO.42 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Thomas A. Holland * Editor with the assistance of Thomas G. Urban oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber THE ROAD TO KADESH A HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION OF THE BATTLE RELIEFS OF KING SETY I AT KARNAK SECOND EDITION REVISED WILLIAM J. MURNANE THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION . NO.42 CHICAGO * ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 90-63725 ISBN: 0-918986-67-2 ISSN: 0081-7554 The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 1985, 1990 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1990. Printed in the United States of America. oi.uchicago.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS List of M aps ................................ ................................. ................................. vi Preface to the Second Edition ................................................................................................. vii Preface to the First Edition ................................................................................................. ix List of Bibliographic Abbreviations ..................................... ....................... xi Chapter 1. Egypt's Relations with Hatti From the Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign ...................................................................... ......................... 1 The Clash of Empires -

The Calendars of Ebla. Part III. Conclusion

Andrews Unir~ersitySeminary Studies, Summer 1981, Vol. 19, No. 2, 115-126 Copyright 1981 by Andrews University Press. THE CALENDARS OF EBLA PART 111: CONCLUSION WILLIAM H. SHEA Andrews University In my two preceding studies of the Old and New Calendars of Ebla (see AUSS 18 [1980]: 127-137, and 19 [1981]: 59-69), interpreta- tions for the meanings of 22 out of 24 of their month names have been suggested. From these studies, it is evident that the month names of the two calendars can be analyzed quite readily from the standpoint of comparative Semitic linguistics. In other words, the calendars are truly Semitic, not Sumerian. Sumerian logograms were used for the names of two months of the Old Calendar and three months of the New Calendar, but it is most likely that the scribes at Ebla read these logograms with a Semitic equivalent. In the cases of the three logograms in the New Calendar these equiva- lents are reasonably clear, but the meanings of the names of the seventh and eighth months in the Old Calendar remain obscure. Not only do these month names lend themselves to a ready analysis on the basis of comparative Semitic linguistics, but, as we have also seen, almost all of them can be analyzed satisfactorily just by comparing them with the vocabulary of biblical Hebrew. Given some simple and well-known phonetic shifts, Hebrew cognates can be suggested for some 20 out of 24 of the month names in these two calendars. Some of the etymologies I have suggested may, of course, be wrong; but even so, the rather full spectrum of Hebrew cognates available for comparison probably would not be diminished greatly. -

John David Hawkins

STUDIA ASIANA – 9 – STUDIA ASIANA Collana fondata da Alfonso Archi, Onofrio Carruba e Franca Pecchioli Daddi Comitato Scientifico Alfonso Archi, Fondazione OrMe – Oriente Mediterraneo Amalia Catagnoti, Università degli Studi di Firenze Anacleto D’Agostino, Università di Pisa Rita Francia, Sapienza – Università di Roma Gianni Marchesi, Alma Mater Studiorum – Università di Bologna Stefania Mazzoni, Università degli Studi di Firenze Valentina Orsi, Università degli Studi di Firenze Marina Pucci, Università degli Studi di Firenze Elena Rova, Università Ca’ Foscari – Venezia Giulia Torri, Università degli Studi di Firenze Sacred Landscapes of Hittites and Luwians Proceedings of the International Conference in Honour of Franca Pecchioli Daddi Florence, February 6th-8th 2014 Edited by Anacleto D’Agostino, Valentina Orsi, Giulia Torri firenze university press 2015 Sacred Landscapes of Hittites and Luwians : proceedings of the International Conference in Honour of Franca Pecchioli Daddi : Florence, February 6th-8th 2014 / edited by Anacleto D'Agostino, Valentina Orsi, Giulia Torri. – Firenze : Firenze University Press, 2015. (Studia Asiana ; 9) http://digital.casalini.it/9788866559047 ISBN 978-88-6655-903-0 (print) ISBN 978-88-6655-904-7 (online) Graphic design: Alberto Pizarro Fernández, Pagina Maestra Front cover photo: Drawing of the rock reliefs at Yazılıkaya (Charles Texier, Description de l'Asie Mineure faite par ordre du Governement français de 1833 à 1837. Typ. de Firmin Didot frères, Paris 1839, planche 72). The volume was published with the contribution of Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze. Peer Review Process All publications are submitted to an external refereeing process under the responsibility of the FUP Editorial Board and the Scientific Committees of the individual series. -

Marten Stol WOMEN in the ANCIENT NEAR EAST

Marten Stol WOMEN IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST Marten Stol Women in the Ancient Near East Marten Stol Women in the Ancient Near East Translated by Helen and Mervyn Richardson ISBN 978-1-61451-323-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-1-61451-263-9 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-1-5015-0021-3 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. Original edition: Vrouwen van Babylon. Prinsessen, priesteressen, prostituees in de bakermat van de cultuur. Uitgeverij Kok, Utrecht (2012). Translated by Helen and Mervyn Richardson © 2016 Walter de Gruyter Inc., Boston/Berlin Cover Image: Marten Stol Typesetting: Dörlemann Satz GmbH & Co. KG, Lemförde Printing and binding: cpi books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Table of Contents Introduction 1 Map 5 1 Her outward appearance 7 1.1 Phases of life 7 1.2 The girl 10 1.3 The virgin 13 1.4 Women’s clothing 17 1.5 Cosmetics and beauty 47 1.6 The language of women 56 1.7 Women’s names 58 2 Marriage 60 2.1 Preparations 62 2.2 Age for marrying 66 2.3 Regulations 67 2.4 The betrothal 72 2.5 The wedding 93 2.6 -

The Story of a Forgotten Kingdom? Survey Archaeology and the Historical Geography of Central Western Anatolia in the Second Millennium BC

European Journal of Archaeology 20 (1) 2017, 120–147 This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The Story of a Forgotten Kingdom? Survey Archaeology and the Historical Geography of Central Western Anatolia in the Second Millennium BC 1,2,3 1,3 CHRISTOPHER H. ROOSEVELT AND CHRISTINA LUKE 1Department of Archaeology and History of Art, Koç University, I˙stanbul, Turkey 2Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations, Koç University, I˙stanbul, Turkey 3Department of Archaeology, Boston University, USA This article presents previously unknown archaeological evidence of a mid-second-millennium BC kingdom located in central western Anatolia. Discovered during the work of the Central Lydia Archaeological Survey in the Marmara Lake basin of the Gediz Valley in western Turkey, the material evidence appears to correlate well with text-based reconstructions of Late Bronze Age historical geog- raphy drawn from Hittite archives. One site in particular—Kaymakçı—stands out as a regional capital and the results of the systematic archaeological survey allow for an understanding of local settlement patterns, moving beyond traditional correlations between historical geography and capital sites alone. Comparison with contemporary sites in central western Anatolia, furthermore, identifies material com- monalities in site forms that may indicate a regional architectural tradition if not just influence from Hittite hegemony. Keywords: survey archaeology, Anatolia, Bronze Age, historical geography, Hittites, Seha River Land INTRODUCTION correlates of historical territories and king- doms have remained elusive.