PROCEEDINGS ס־ סכ Oo M M ס Z O (0 NOVEMBER 14-18, 1971

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Debate Over Mixed Seating in the American Synagogue

Jack Wertheimer (ed.) The American Synagogue: A Sanctuary Transformed. New York: Cambridge 13 University Press, 1987 The Debate over Mixed Seating in the American Synagogue JONATHAN D. SARNA "Pues have never yet found an historian," John M. Neale com plained, when he undertook to survey the subject of church seating for the Cambridge Camden Society in 1842. 1 To a large extent, the same situation prevails today in connection with "pues" in the American syn agogue. Although it is common knowledge that American synagogue seating patterns have changed greatly over time - sometimes following acrimonious, even violent disputes - the subject as a whole remains unstudied, seemingly too arcane for historians to bother with. 2 Seating patterns, however, actually reflect down-to-earth social realities, and are richly deserving of study. Behind wearisome debates over how sanctuary seats should be arranged and allocated lie fundamental disagreements over the kinds of social and religious values that the synagogue should project and the relationship between the synagogue and the larger society that surrounds it. As we shall see, where people sit reveals much about what they believe. The necessarily limited study of seating patterns that follows focuses only on the most important and controversial seating innovation in the American synagogue: mixed (family) seating. Other innovations - seats that no longer face east, 3 pulpits moved from center to front, 4 free (un assigned) seating, closed-off pew ends, and the like - require separate treatment. As we shall see, mixed seating is a ramified and multifaceted issue that clearly reflects the impact of American values on synagogue life, for it pits family unity, sexual equality, and modernity against the accepted Jewish legal (halachic) practice of sexual separatiop in prayer. -

A Synagogue for All Families: Interfaith Inclusion in Conservative Synagogues

A Synagogue for All Families Interfaith Inclusion in Conservative Synagogues Introduction Across North America, Conservative kehillot (synagogues) create programs, policies, and welcoming statements to be inclusive of interfaith families and to model what it means for 21st century synagogues to serve 21 century families. While much work remains, many professionals and lay leaders in Conservative synagogues are leading the charge to ensure that their community reflects the prophet Isaiah’s vision that God’s house “shall be a house of prayer for all people” (56:7). In order to share these congregational exemplars with other leaders who want to raise the bar for inclusion of interfaith families in Conservative Judaism, the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism (USCJ) and InterfaithFamily (IFF) collaborated to create this Interfaith Inclusion Resource for Conservative Synagogues. This is not an exhaustive list, but a starting point. This document highlights 10 examples where Conservative synagogues of varying sizes and locations model inclusivity in marketing, governance, pastoral counseling and other key areas of congregational life. Our hope is that all congregations will be inspired to think as creatively as possible to embrace congregants where they are, and encourage meaningful engagement in the synagogue and the Jewish community. We are optimistic that this may help some synagogues that have not yet begun the essential work of the inclusion of interfaith families to find a starting point that works for them. Different synagogues may be in different places along the spectrum of welcoming and inclusion. Likewise, the examples presented here reflect a spectrum, from beginning steps to deeper levels of commitment, and may evolve as synagogues continue to engage their congregants in interfaith families. -

Examining Nostra Aetate After 40 Years: Catholic-Jewish Relations in Our Time / Edited by Anthony J

EXAMINING NOSTRA AETATE AFTER 40 YEARS EXAMINING NOSTRA AETATE AFTER 40 YEARS Catholic-Jewish Relations in Our Time Edited by Anthony J. Cernera SACRED HEART UNIVERSITY PRESS FAIRFIELD, CONNECTICUT 2007 Copyright 2007 by the Sacred Heart University Press All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, contact the Sacred Heart University Press, 5151 Park Avenue, Fairfield, Connecticut 06825 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Examining Nostra Aetate after 40 Years: Catholic-Jewish Relations in our time / edited by Anthony J. Cernera. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-888112-15-3 1. Judaism–Relations–Catholic Church. 2. Catholic Church– Relations–Judaism. 3. Vatican Council (2nd: 1962-1965). Declaratio de ecclesiae habitudine ad religiones non-Christianas. I. Cernera, Anthony J., 1950- BM535. E936 2007 261.2’6–dc22 2007026523 Contents Preface vii Nostra Aetate Revisited Edward Idris Cardinal Cassidy 1 The Teaching of the Second Vatican Council on Jews and Judaism Lawrence E. Frizzell 35 A Bridge to New Christian-Jewish Understanding: Nostra Aetate at 40 John T. Pawlikowski 57 Progress in Jewish-Christian Dialogue Mordecai Waxman 78 Landmarks and Landmines in Jewish-Christian Relations Judith Hershcopf Banki 95 Catholics and Jews: Twenty Centuries and Counting Eugene Fisher 106 The Center for Christian-Jewish Understanding of Sacred Heart University: -

Data Maturity for Synagogues: Incorporating Data Into the Decision-Making Culture Prepared by Idealware © 2014 UJA-Federation of New York

VOLUME 9 | 2015 | 5775 UJA-Federation of New York SYNERGY Innovations and Strategies for Synagogues of Tomorrow DATA MATURITY FOR SYNAGOGUES: INCORPORATING DATA INTO THE DECISION-MAKING CULTURE Prepared by Idealware © 2014 UJA-Federation of New York 1 INTRODUCTION For years, UJA-Federation of New York has been exploring how data-informed decision making can MAKINGhelp synagogues DATA PART thrive. OFThrough THE the DECISION-MAKING Sustainable Synagogues CULTUREBusiness Models project, facilitated by Measuring Success from 2009 to 2012, UJA-Federation learned that thriving synagogues regularly assess and make decisions based on the extent to which their communal vision, mission, and values are aligned with all aspects of synagogue life. We also learned that it matters which systems synagogues SELF-ASSESSMENTuse to collect data. In order TOOL to help synagogues assess which system might meet their particular needs, UJA-Federation funded the development of “A Guide to Synagogue Management Systems: Research and Recommendations,” and more recently a 2014 update, in collaboration with the Orthodox Union (OU), THEUnion DATA for ReformMATURITY Judaism PROGRESSION (URJ), and United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism (USCJ). Furthermore, we have also learned through observations in the field that synagogues are not simply “data-driven or not data-driven.” Rather, there is a broad spectrum of data maturity, beginning with simple data collection and moving along the spectrum in complexity to reflect more sophisticated SUPPORTINGuses of data. THE JEWISH IDENTITY OF INDIVIDUALS AND THE COMMUNITY This paper reflects UJA-Federation's commitment to identifying and sharing innovations and strategies METHODOLOGYthat can support synagogues on their journeys to become thriving congregations. -

Donald Kalish Papers LSC.0578

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8x06bbs No online items Finding Aid for the Donald Kalish Papers LSC.0578 UCLA Library Special Collections staff, 2004-2006; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. Additions processed by Krystell Jimenez in the Center for Primary Research and Training (CFPRT) in 2018, under the supervision of Angel Diaz. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated 27 July 2018. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the Donald Kalish LSC.0578 1 Papers LSC.0578 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Donald Kalish papers Creator: Kalish, Donald Identifier/Call Number: LSC.0578 Physical Description: 91.2 Linear Feet(228 boxes) Date (bulk): 1927-2000 Abstract: Donald Kalish, born December 4, 1919, was a logician, UCLA professor, and anti-war activist. His areas of expertise included logic and set theory. Kalish was known for his activism and opposition to the Vietnam War, as well as US military involvement in Central America and for hiring Angela Davis in 1969. This collection consists of materials related to Kalish's writings, teaching career, research, political activities, and personal life. The papers include course materials, lecture notes, correspondence, scrapbooks, political ephemera, newspaper clippings, photographs, and audio tapes. Language of Material: Materials are in English. Stored off-site at SRLF. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. -

124900176.Pdf

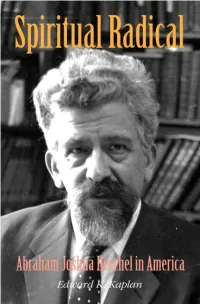

Spiritual Radical EDWARD K. KAPLAN Yale University Press / New Haven & London [To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Spiritual Radical Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund. Copyright © 2007 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Bodoni type by Binghamton Valley Composition. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kaplan, Edward K., 1942– Spiritual radical : Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 / Edward K. Kaplan.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-11540-6 (alk. paper) 1. Heschel, Abraham Joshua, 1907–1972. 2. Rabbis—United States—Biography. 3. Jewish scholars—United States—Biography. I. Title. BM755.H34K375 2007 296.3'092—dc22 [B] 2007002775 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10987654321 To my wife, Janna Contents Introduction ix Part One • Cincinnati: The War Years 1 1 First Year in America (1940–1941) 4 2 Hebrew Union College -

SENCO Special Educational Needs Co-Ordinator

Special Needs 1 A guide for parents and carers of Jewish children with special educational needs Compiled under the auspices of the Board of Deputies, 6 Bloomsbury Square London WC1A 2LP Special Needs 2 Acknowledgements Many people contributed to the development of this booklet in what was truly a combined effort. The production team included Sharon Bourla of Norwood Ravenswood, Ella Marks of the League of Jewish Women and the Board of Deputies, Amanda Moss from Kisharon, Sandy Patashnik from the Agency for Jewish Education, Philippa Travis from the Board of Deputies, and Marlena Schmool and Samantha Blendis of the Board. The original inspiration came from Susan Pascoe, a member of the Community Issues Divisional Board of the Board of Deputies, without her the task would never have been undertaken and she is especially to be thanked for her guidance. We are also indebted to The Ashdown Trust, The Kessler Foundation and The J E Joseph Charitable Trust for making the production possible. We thank them for their generosity and support. Special Needs 3 Preface This guide has been developed in response to a need. It aims to draw together in a ‘one-stop booklet’, information which will help parents of Jewish children with special needs. Specifically, it seeks to advise them where to go to obtain support and assistance at different stages in their children’s lives, covering both general and Jewish aspects. It has been a co- operative initiative in which the Board of Deputies, Norwood Ravenswood, Kisharon and the Agency for Jewish Education have all been involved. -

Bombing for Justice: Urban Terrorism in New York City from the 1960S Through the 1980S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2014 Bombing for Justice: Urban Terrorism in New York City from the 1960s through the 1980s Jeffrey A. Kroessler John Jay College of Criminal Justice How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/38 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Bombing for Justice: Urban Terrorism in New York City from the 1960s through to the 1980s Jeffrey A. Kroessler John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York ew York is no stranger to explosives. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Black Hand, forerunners of the Mafia, planted bombs at stores and residences belonging to successful NItalians as a tactic in extortion schemes. To combat this evil, the New York Police Department (NYPD) founded the Italian Squad under Lieutenant Joseph Petrosino, who enthusiastically pursued those gangsters. Petrosino was assassinated in Palermo, Sicily, while investigating the criminal back- ground of mobsters active in New York. The Italian Squad was the gen- esis of today’s Bomb Squad. In the early decades of the twentieth century, anarchists and labor radicals planted bombs, the most devastating the 63 64 Criminal Justice and Law Enforcement noontime explosion on Wall Street in 1920. That crime was never solved.1 The city has also had its share of lunatics. -

Personal Material

1 MS 377 A3059 Papers of William Frankel Personal material Papers, correspondence and memorabilia 1/1/1 A photocopy of a handwritten copy of the Sinaist, 1929; 1929-2004 Some correspondence between Terence Prittie and Isaiah Berlin; JPR newsletters and papers regarding a celebration dinner in honour of Frankel; Correspondence; Frankel’s ID card from a conference; A printed article by Frankel 1/1/2 A letter from Frankel’s mother; 1936-64 Frankel’s initial correspondence with the American Jewish Committee; Correspondence from Neville Laski; Some papers in Hebrew; Papers concerning B’nai B’rith and Professor Sir Percy Winfield; Frankel’s BA Law degree certificate 1/1/3 Photographs; 1937-2002 Postcards from Vienna to I.Frankel, 1937; A newspaper cutting about Frankel’s meeting with Einstein, 2000; A booklet about resettlement in California; Notes of conversations between Frankel and Golda Meir, Abba Eban and Dr. Adenauer; Correspondence about Frankel’s letter to The Times on Shylock; An article on Petticoat lane and about London’s East End; Notes from a speech on the Jewish Chronicle’s 120th anniversary dinner; Notes for speech on Israel’s prime ministers; Papers concerning post-WW2 Jewish education 1/1/4 JPR newsletters; 1938-2006 Notes on Harold Wilson and 1974 General Election; Notes on and correspondence with Oswald Mosley, 1966 Correspondence including with Isaiah Berlin, Joseph Leftwich, Dr Louis Rabinowitz, Raphael Lowe, Wolfe Kelman, A.Krausz, Norman Cohen and Dr. E.Golombok 1/1/5 Printed and published articles by Frankel; 1939, 1959-92 Typescripts, some annotated, for talks and regarding travels; Correspondence including with Lord Boothby; MS 377 2 A3059 Records of conversations with Dr. -

Directories Lists Necrology National Jewish Organizations1

Directories Lists Necrology National Jewish Organizations1 UNITED STATES Organizations are listed according to functions as follows: Religious, Educational 305 Cultural 299 Community Relations 295 Overseas Aid 302 Social Welfare 323 Social, Mutual Benefit 321 Zionist and Pro-Israel 326 Note also cross-references under these headings: Professional Associations 334 Women's Organizations 334 Youth and Student Organizations 335 COMMUNITY RELATIONS Gutman. Applies Jewish values of justice and humanity to the Arab-Israel conflict in AMERICAN COUNCIL FOR JUDAISM (1943). the Middle East; rejects nationality attach- 307 Fifth Ave., Suite 1006, N.Y.C., 10016. ment of Jews, particularly American Jews, (212)889-1313. Pres. Clarence L. Cole- to the State of Israel as self-segregating, man, Jr.; Sec. Alan V. Stone. Seeks to ad- inconsistent with American constitutional vance the universal principles of a Judaism concepts of individual citizenship and sep- free of nationalism, and the national, civic, aration of church and state, and as being a cultural, and social integration into Ameri- principal obstacle to Middle East peace, can institutions of Americans of Jewish Report. faith. Issues of the American Council for Judaism; Special Interest Report AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE (1906). In- stitute of Human Relations, 165 E. 56 St., AMERICAN JEWISH ALTERNATIVES TO N.Y.C., 10022. (212)751-4000. Pres. May- ZIONISM, INC. (1968). 133 E. 73 St., nard I. Wishner; Exec. V. Pres. Bertram H. N.Y.C., 10021. (212)628-2727. Pres. Gold. Seeks to prevent infraction of civil Elmer Berger; V. Pres. Mrs. Arthur and religious rights of Jews in any part of 'The information in this directory is based on replies to questionnaires circulated by the editors. -

Ethnicity and Faith in American Judaism: Reconstructionism As Ideology and Institution, 1935-1959

ETHNICITY AND FAITH IN AMERICAN JUDAISM: RECONSTRUCTIONISM AS IDEOLOGY AND INSTITUTION, 1935-1959 A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Deborah Waxman May, 2010 Examining Committee Members: Lila Corwin Berman, Advisory Chair, History David Harrington Watt, History Rebecca Trachtenberg Alpert, Religion Deborah Dash Moore, External Member, University of Michigan ii ABSTRACT Title: Ethnicity and Faith in American Judaism: Reconstructionism as Ideology and Institution, 1935-1959 Candidate's Name: Deborah Waxman Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2010 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Lila Corwin Berman This dissertation addresses the development of the movement of Reconstructionist Judaism in the period between 1935 and 1959 through an examination of ideological writings and institution-building efforts. It focuses on Reconstructionist rhetorical strategies, their efforts to establish a liberal basis of religious authority, and theories of cultural production. It argues that Reconstructionist ideologues helped to create a concept of ethnicity for Jews and non-Jews alike that was distinct both from earlier ―racial‖ constructions or strictly religious understandings of modern Jewish identity. iii DEDICATION To Christina, who loves being Jewish, With gratitude and abundant love iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation is the product of ten years of doctoral studies, so I type these words of grateful acknowledgment with a combination of astonishment and excitement that I have reached this point. I have been inspired by extraordinary teachers throughout my studies. As an undergraduate at Columbia, Randall Balmer introduced me to the study of American religious history and Holland Hendrix encouraged me to take seriously the prospect of graduate studies. -

(I) the Five Jewish Influences on Ramah

THE JACOB RADER MARCUS CENTER OF THE AMERICAN JEWISH ARCHIVES MS-831: Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Foundation Records, 1980–2008. Series C: Council for Initiatives in Jewish Education (CIJE). 1988–2003. Subseries 5: Communication, Publications, and Research Papers, 1991–2003. Box Folder 42 2 Fox, Seymour, and William Novak. Vision at the Heart. Planning and drafts, February 1996-May 1996. For more information on this collection, please see the finding aid on the American Jewish Archives website. 3101 Clifton Ave, Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 513.487.3000 AmericanJewishArchives.org FROM: "Dan Pekarsky", INTERNET:[email protected] TO: Nessa Rapoport, 74671,3370 Nessa Rapoport, 74671,3370 DATE: 2/5/96 10:19 AM Re: Ramah and my paper Sender: [email protected] Received: from audumla.students.wisc.edu (students.wisc.edu [144.92.104.66]) by dub-img-4.compuserve.com (8.6.10/5.950515) id JAA22229; Mon, 5 Feb 1996 09:56:41 -0500 Received: from mail.soemadison.wisc.edu by audumla.students.wisc.edu; id IAA111626 ; 8.6.9W/42; Mon, 5 Feb 1996 08:56:40 -0600 From: "Dan Pekarsky" <[email protected]> Reply-To: [email protected] To: [email protected], [email protected] Date: Sun, 04 Feb 1996 21 :12:00 -600 Subject: Ramah and my paper X-Gateway: iGate, (WP Office) vers 4.04m - 1032 MIME-Version: 1.0 Message-Id: <[email protected]> Content-Type: TEXT/PLAIN; Charset=US-ASCII Content-Transfer-Encoding: ?BIT Nessa, I am finding the in-progress Ramah piece very interesting, and I'm struck by the number of times my own intuitive reactions are mirrored a few lines down by your own comments in the brackets.