CONSERVATIVE JUDAISM: Volume XVIII, Number 1, Fall 1963 Published by the Rabbinical Assembly. EDITOR: Samuel H. Dresner. DEPARTM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examining Nostra Aetate After 40 Years: Catholic-Jewish Relations in Our Time / Edited by Anthony J

EXAMINING NOSTRA AETATE AFTER 40 YEARS EXAMINING NOSTRA AETATE AFTER 40 YEARS Catholic-Jewish Relations in Our Time Edited by Anthony J. Cernera SACRED HEART UNIVERSITY PRESS FAIRFIELD, CONNECTICUT 2007 Copyright 2007 by the Sacred Heart University Press All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, contact the Sacred Heart University Press, 5151 Park Avenue, Fairfield, Connecticut 06825 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Examining Nostra Aetate after 40 Years: Catholic-Jewish Relations in our time / edited by Anthony J. Cernera. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-888112-15-3 1. Judaism–Relations–Catholic Church. 2. Catholic Church– Relations–Judaism. 3. Vatican Council (2nd: 1962-1965). Declaratio de ecclesiae habitudine ad religiones non-Christianas. I. Cernera, Anthony J., 1950- BM535. E936 2007 261.2’6–dc22 2007026523 Contents Preface vii Nostra Aetate Revisited Edward Idris Cardinal Cassidy 1 The Teaching of the Second Vatican Council on Jews and Judaism Lawrence E. Frizzell 35 A Bridge to New Christian-Jewish Understanding: Nostra Aetate at 40 John T. Pawlikowski 57 Progress in Jewish-Christian Dialogue Mordecai Waxman 78 Landmarks and Landmines in Jewish-Christian Relations Judith Hershcopf Banki 95 Catholics and Jews: Twenty Centuries and Counting Eugene Fisher 106 The Center for Christian-Jewish Understanding of Sacred Heart University: -

The Question of Yom Tov Sheini for Visitors to Israel RABBI MAYER RABINOWITZ

The Question of Yom Tov Sheini for Visitors to Israel RABBI MAYER RABINOWITZ This paper was adopted on May 28, 1981 by a vote of 12-2-1. Members voting in favor: Rabbis Kassel Abelson, Ephraim L. Bennett, Ben Zion Bokser, David M. Feldman, Wolfe Kelman, David H. Lincoln, Mayer E. Rabinowitz, Alexander M. Shapiro, Morris M. Shapiro, Israel N. Silverman, Harry Z. Sky and Henry A. Sosland. Members voting in opposition: Rabbis Joel Roth and Phillip Sigal. Abstaining: Rabbi Edward M. Gershfield. SHE'ELAH Should a visitor to Israel observe Yom Tov Sheini or should he follow the custom of Eretz Yisrael to only observe one day of a Yom Tov? TESHUVAH The prevailing practice has been that a visitor to Israel observes Yom Tov Sheini. This is based on Mishnah Pesahim 4:1: Notnin alav humrei makom sheyatza misham ve/Jumrei makom shehalakh lesham (We impose on him the restrictions of the place from where he came and the restrictions of the place where he has gone). Based upon the discussion in the Gemara Pesahim 5la, and following the opinion of Rav Ashi that the Mishnah refers to a person who intends to return to his place of abode (da'ato lahzor), many posekim have stated that visitors to Israel must obseiVe Yom Tov Sheini if they intend to return to the Diaspora (Arukh H ashulhan, Orah Hayyim 496:5; Mishnah Berurah, ibid., par. 13). InMa'aseh Geonim (no. 47, pp. 31-32), we find the opinion that a visitor to Israel must observe Yom Tov Sheini. Only after dwelling in Israel for twelve months would the "visitor" be considered a resident and a part of the community. -

“Official Position” of the CJLS Nor of the Rabbinical Assembly

N.B. This paper represents solely the opinion of the author and is not an “official position” of the CJLS nor of the Rabbinical Assembly. Emergency Ruling in Regard to Livestreaming Services Rabbi David J Fine, PhD President, New Jersey Rabbinical Assembly March 14, 2020 Psak Din: In the current state of emergency, where most of our congregations have closed their doors in the midst of the containment efforts of the COVID-19 crisis, live streamed services of even a single individual (the shaliah tzibbur) may be deemed a minyan when at least nine others eligible to count in a minyan are connected to the site at the time of the live streaming. In 2001, the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative movement (CJLS) approved a responsum by Rabbi Avram Israel Reisner by a vote of 18-2, that permitted one to perform one’s obligation to participate in prayer, hear the Torah, shofar, megillah and say kaddish when connected to a minyan through the internet. However, Rabbi Reisner required a minyan of ten eligible Jews to constitute a live minyan at the source of the “broadcast.” That decision was reasoned through a careful reading of the relevant precedents regarding when one can fulfill an obligation when in “ear-shot” but not in the same room as the minyan, and gave important consideration as well to the importance of live face-to-face gatherings. In the nineteen years that have passed since Rabbi Reisner’s paper was approved by the CJLS, we have seen an extraordinary increase in the development and use of technology towards virtual meeting space. -

Conservative Judaism Journal Volume 26 No. 3, Spring 1972

The Ethical Dl THE ETWCAL DIMENSION IN THE BALAKBAB Rabbi Si of ethical va Ionian. Accm to the Templ year, Rabban only one offE Robert Gordis came from a card their or• after the ho In memory of Dr. Michael Higger, on his twentieth yahrzeit. demand and and proclain THE CHARACIER AND EX1ENT of the ideological "pluralism" prevalent in Conser broken befm vative Judaism today-which unsympathetic critics might describe as chaos and These~ lack of direction-are highlighted by two papers that appeared in the Spring sitivity of tb 1971 issue of CONSERVATIVE JUDAISM, Rabbi Seymour Siegel's article "Ethics and in each case the Halakhah," and Rabbi Abraham Goldberg's article "Jewish Law and Religious space, affect Values in the Secular State." tions did no Basic to Dr. Siegel's paper is the principle he enunciates: "If any law in Fleecing the our tradition does not fulfill our ethical values, then the law should be abolished tions of this or revised. This point of view can be supported historically and theologically." Even m He buttresses his standpoint with the biblical doctrine of man having been lullaklulh in created in the image of God and therefore being commanded to imitate the earlier positi Divine virtues. establish ne' This position may be supported by a theology of Torah as well. It is clear and perman1 that all the greatest teachers of Judaism during the most creative periods of our testimony of history would have found it unconscionable to admit that the Torah, the eternal of their ethic Revelation of an eternal God interpreted by the masters of tradition, could prove ness. -

124900176.Pdf

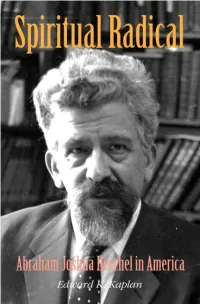

Spiritual Radical EDWARD K. KAPLAN Yale University Press / New Haven & London [To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Spiritual Radical Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund. Copyright © 2007 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Bodoni type by Binghamton Valley Composition. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kaplan, Edward K., 1942– Spiritual radical : Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 / Edward K. Kaplan.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-11540-6 (alk. paper) 1. Heschel, Abraham Joshua, 1907–1972. 2. Rabbis—United States—Biography. 3. Jewish scholars—United States—Biography. I. Title. BM755.H34K375 2007 296.3'092—dc22 [B] 2007002775 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10987654321 To my wife, Janna Contents Introduction ix Part One • Cincinnati: The War Years 1 1 First Year in America (1940–1941) 4 2 Hebrew Union College -

Translator's Preface

Translator’s Preface It is over sixty years since Isaac Heinemann wrote his monumental work Ta’amei Ha-Mitzvot, based on his lectures at the Jewish Theological Seminary of Breslau in the 1930s. Yet barriers of language and cultural frame-of- reference have denied this work the influence it rightly should have had in Jewish thought. There are echoes of his approach in the method and writings of Abraham J. Heschel and Seymour Siegel, but the contemporary discussion of halakhic authority still has much to learn from his analytical approach and his scholarship on this topic. Isaac Heinemann (1876–1957) was a leading humanistic and Judaic scholar who enriched his generation’s understanding of Hellenistic and rabbinic Jewish thought in his important studies on Philo and the Aggadah of the rabbis, and his many years of teaching in Europe and in Israel. His Darkhei Ha-Aggadah (“The Ways of the Aggadah”) still stands as a leading appreciation of the relation of form and message in rabbinic non-legal litera- ture. The current volume turns to the legal thought of the rabbis as understood by many generations of pre-modern Jewish thinkers. It addresses a central topic that is vital to the substance of Jewish religious life in all its forms, under whatever denominational label (or lack thereof) it may be practiced. Heinemann represented a traditionalism that did not align itself strictly with the modern party lines of Jewry. He taught at one of the institutions of European Conservative Judaism final and had his work published in Israel by the youth movement of Mizrahi, representing modern Ortho- doxy. -

Conservatism Is Not Reconstructionism Seymour Siegel

Movement did in the cases of mamzerut (illegitimacy) in the Conservative Movement, I am aware that and kohen (priest) and th egerushah (divorced woman)? we might have done better. But it serves no Let's call a spade a spade. purpose to denigrate what was done. New Philosophy of Halacha Needed Finally, I think it's time to state a few facts force- The Commission's report states that it is not fully and to draw from them the conclusion to "charged with developing an halachic stance for which I have been heading - we ought now to the Conservative Movement." The Commission acknowledge that we need a new philosophy for was responsible to advise the Faculty of the the legislation of law in Jewish life and for the Jewish Theological Seminary — the most tradi- creative continuity of a ritual tradition without tionalist arm of the Conservative Movement — which Judaism lacks inspiration and emotional on the question of the ordination of women. It power. came up with an overwhelming majority for ordination. This is a noteworthy achievement. I regret that there is little likelihood that most of the Orthodox will be open to real dialogue on The Conservative Movement, as a whole, has the subject, but they should be viewed by us as developed a substantial literature exploiting its the modern Karaites, incapable of going beyond halachic approach. It has, especially in the past the confines of an Oral Law which has taken on several years, made noteworthy progress in the all the trappings of a Written Law whose premises field of Jewish law. -

Personal Material

1 MS 377 A3059 Papers of William Frankel Personal material Papers, correspondence and memorabilia 1/1/1 A photocopy of a handwritten copy of the Sinaist, 1929; 1929-2004 Some correspondence between Terence Prittie and Isaiah Berlin; JPR newsletters and papers regarding a celebration dinner in honour of Frankel; Correspondence; Frankel’s ID card from a conference; A printed article by Frankel 1/1/2 A letter from Frankel’s mother; 1936-64 Frankel’s initial correspondence with the American Jewish Committee; Correspondence from Neville Laski; Some papers in Hebrew; Papers concerning B’nai B’rith and Professor Sir Percy Winfield; Frankel’s BA Law degree certificate 1/1/3 Photographs; 1937-2002 Postcards from Vienna to I.Frankel, 1937; A newspaper cutting about Frankel’s meeting with Einstein, 2000; A booklet about resettlement in California; Notes of conversations between Frankel and Golda Meir, Abba Eban and Dr. Adenauer; Correspondence about Frankel’s letter to The Times on Shylock; An article on Petticoat lane and about London’s East End; Notes from a speech on the Jewish Chronicle’s 120th anniversary dinner; Notes for speech on Israel’s prime ministers; Papers concerning post-WW2 Jewish education 1/1/4 JPR newsletters; 1938-2006 Notes on Harold Wilson and 1974 General Election; Notes on and correspondence with Oswald Mosley, 1966 Correspondence including with Isaiah Berlin, Joseph Leftwich, Dr Louis Rabinowitz, Raphael Lowe, Wolfe Kelman, A.Krausz, Norman Cohen and Dr. E.Golombok 1/1/5 Printed and published articles by Frankel; 1939, 1959-92 Typescripts, some annotated, for talks and regarding travels; Correspondence including with Lord Boothby; MS 377 2 A3059 Records of conversations with Dr. -

Kol Shofar Kashrut Policy and Guide Table of Contents

Kol Shofar Kashrut Policy and Guide Table of Contents Policy Introduction 2 Food Preparation in the Kol Shofar Kitchen 2 Community Member Use of the Kitchen 3 Shared Foods / Potlucks 3 Home-Cooked Food / Community Potlucks 3 Field Trips, Off-site Events and Overnights 3 Personal / Individual Consumption 4 Local Kosher Establishments 5 Pre-Approved Caterers and Bakeries Kashrut Glossary 6 Essential Laws 7 Top Ten Kosher Symbols 8 Further Reading 9 1 A Caring Kol Shofar Community Kashrut Guidelines for Synagogue and Youth Education It is possible sometimes to come closer to God when you are involved in material activities like eating and drinking than when you are involved with “religious” activities like Torah study and prayer. - Rabbi Abraham of Slonim, Torat Avot Kol Shofar is a vibrant community comprised of a synagogue and a school. Informed by the standards of the Conservative Movement, we revere the mitzvot (ritual and ethical commandments) both as the stepping-stones along the path toward holiness and as points of interpersonal connection. In this light, mitzvot are manners of spiritual expression that allow each of us to individually relate to God and to one another. Indeed, it is through the mitzvot that we encounter a sacred partnership, linked by a sacred brit (covenant), in which we embrace the gift of life together and strive to make the world more holy and compassionate. Mitzvot, like Judaism itself, are evolving and dynamic and not every one of us will agree with what constitutes each and every mitzvah at each moment; indeed, we embrace and celebrate the diversity of the Jewish people. -

Toward Jewish Religious Unity: a Symposium

Toward Jewish Religious Unity: A Symposium IRVING GREENBERG MORDECAI M. KAPLAN JAKOB J. PETUCHOWSKI SEYMOUR SIEGEL Last winter, JUDAISM, in conjunction with its anmrnl meeting of the Board of Editors, invited IRVING GREENBERG, MORDECAI M. KAl'LAN, JAKOB J· PETU CHOWSKI, • and SEYMOUR SIEGEL to present papers and participate in a symposium on the theme: "Jewish Religious Unity: Is It Possible1" The discussion, held before an invited audience, was chaired by STEiVEN s. SCUWARZSCHILD, editor of JUDAISM ancl associate professor of philosophy at Washington University in St. Louis. What follows is a transcript of the proceedings. IRVING C!lEENllERG is associate professor of history at Yeshiva Univer~ s~ty and rabbi of the Riverdale Jewish Center in New York 'City. MORDECAI M. KAl'l.AN, one of the most respected religious ·teachers in American Jewry, is the founder of the Rcconstructionist movement and the author of Judaism as a Civilization, The Future. of the American Jew, and many other works. He i~ ·currently teaching at the UniVersity of ,,;: Judaism in Los Angeles, , the West ·Coast branch of the Jewish Theologi· cal Seminary of America. JAKOB J· PETUcnowsKt, professor of rabbinics at Hebrew Union Col lege-Jewish Institute of Religion in Cincinnati, has written widely in the field of Jewish theology. His most recent book is Ever Since Sinai A Modern View of Torah. SEYMOUR SIEGEL, an officer of the Rabbinical Assembly of America, is assistant professor of Talmud , at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. STEVEN S. SCHW ARZSCHILD THE THEME OF OUR SYMPOSIUM IS SOMEWHAT DIFFICULT TO DEFINE. MY own-:-awkward-working Litle, arrived at after much deliberation, was finally formuJated as: "What Are the Foundatioi1s for the · Future Re ligious Unity of the People of Israel?" Let me explain what I mean. -

Directories Lists Necrology National Jewish Organizations1

Directories Lists Necrology National Jewish Organizations1 UNITED STATES Organizations are listed according to functions as follows: Religious, Educational 305 Cultural 299 Community Relations 295 Overseas Aid 302 Social Welfare 323 Social, Mutual Benefit 321 Zionist and Pro-Israel 326 Note also cross-references under these headings: Professional Associations 334 Women's Organizations 334 Youth and Student Organizations 335 COMMUNITY RELATIONS Gutman. Applies Jewish values of justice and humanity to the Arab-Israel conflict in AMERICAN COUNCIL FOR JUDAISM (1943). the Middle East; rejects nationality attach- 307 Fifth Ave., Suite 1006, N.Y.C., 10016. ment of Jews, particularly American Jews, (212)889-1313. Pres. Clarence L. Cole- to the State of Israel as self-segregating, man, Jr.; Sec. Alan V. Stone. Seeks to ad- inconsistent with American constitutional vance the universal principles of a Judaism concepts of individual citizenship and sep- free of nationalism, and the national, civic, aration of church and state, and as being a cultural, and social integration into Ameri- principal obstacle to Middle East peace, can institutions of Americans of Jewish Report. faith. Issues of the American Council for Judaism; Special Interest Report AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE (1906). In- stitute of Human Relations, 165 E. 56 St., AMERICAN JEWISH ALTERNATIVES TO N.Y.C., 10022. (212)751-4000. Pres. May- ZIONISM, INC. (1968). 133 E. 73 St., nard I. Wishner; Exec. V. Pres. Bertram H. N.Y.C., 10021. (212)628-2727. Pres. Gold. Seeks to prevent infraction of civil Elmer Berger; V. Pres. Mrs. Arthur and religious rights of Jews in any part of 'The information in this directory is based on replies to questionnaires circulated by the editors. -

Ethnicity and Faith in American Judaism: Reconstructionism As Ideology and Institution, 1935-1959

ETHNICITY AND FAITH IN AMERICAN JUDAISM: RECONSTRUCTIONISM AS IDEOLOGY AND INSTITUTION, 1935-1959 A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Deborah Waxman May, 2010 Examining Committee Members: Lila Corwin Berman, Advisory Chair, History David Harrington Watt, History Rebecca Trachtenberg Alpert, Religion Deborah Dash Moore, External Member, University of Michigan ii ABSTRACT Title: Ethnicity and Faith in American Judaism: Reconstructionism as Ideology and Institution, 1935-1959 Candidate's Name: Deborah Waxman Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2010 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Lila Corwin Berman This dissertation addresses the development of the movement of Reconstructionist Judaism in the period between 1935 and 1959 through an examination of ideological writings and institution-building efforts. It focuses on Reconstructionist rhetorical strategies, their efforts to establish a liberal basis of religious authority, and theories of cultural production. It argues that Reconstructionist ideologues helped to create a concept of ethnicity for Jews and non-Jews alike that was distinct both from earlier ―racial‖ constructions or strictly religious understandings of modern Jewish identity. iii DEDICATION To Christina, who loves being Jewish, With gratitude and abundant love iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation is the product of ten years of doctoral studies, so I type these words of grateful acknowledgment with a combination of astonishment and excitement that I have reached this point. I have been inspired by extraordinary teachers throughout my studies. As an undergraduate at Columbia, Randall Balmer introduced me to the study of American religious history and Holland Hendrix encouraged me to take seriously the prospect of graduate studies.