Report on the Composition of Prevalent Salt Varieties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latest Press Release from Consensus Action on Salt and Health

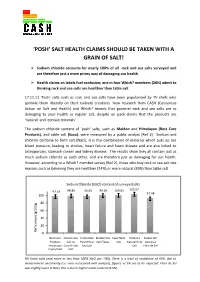

‘POSH’ SALT HEALTH CLAIMS SHOULD BE TAKEN WITH A GRAIN OF SALT! Sodium chloride accounts for nearly 100% of all rock and sea salts surveyed and are therefore just a more pricey way of damaging our health Health claims on labels fuel confusion; one in four Which? members (28%) admit to thinking rock and sea salts are healthier than table salt 17.11.11 ‘Posh’ salts such as rock and sea salts have been popularised by TV chefs who sprinkle them liberally on their culinary creations. New research from CASH (Consensus Action on Salt and Health) and Which? reveals that gourmet rock and sea salts are as damaging to your health as regular salt, despite on pack claims that the products are ‘natural’ and ‘contain minerals’. The sodium chloride content of ‘posh’ salts, such as Maldon and Himalayan (Best Care Products), and table salt (Saxa), were measured by a public analyst [Ref 1]. Sodium and chloride combine to form salt (NaCl), it is this combination of minerals which puts up our blood pressure, leading to strokes, heart failure and heart disease and are also linked to osteoporosis, stomach cancer and kidney disease. The results show they all contain just as much sodium chloride as each other, and are therefore just as damaging for our health. However, according to a Which? member survey [Ref 2], those who buy rock or sea salt cite reasons such as believing they are healthier (24%) or more natural (39%) than table salt. Sodium Chloride (NaCl) content of surveyed salts 98.86 96.65 99.50 100.65 103.57 97.19 91.48 100 80 60 40 20 NaCl contentNaCl (g/100g) 0 Best Care Cornish Sea Halen Mon Maldon Sea Saxa Table Tidman's Zauber der Products Salt Co Pure White Salt Flakes Salt Natural Rock Gewürze Himalayan Cornish Sea Sea Salt Salt Fleur de Sel Crystal Salt Salt NB Some salts total more or less than 100% NaCl per 100g. -

LAS VEGAS PRODUCT CATALOG INGREDIENTS Full Page Ad for FINE PASTRY 11”X 8.5”

PRODUCT CATALOG LAS VEGAS chefswarehouse.com BAKING AND PASTRY FROZEN/RTB BREAD ...................12 BEVERAGES, GOAT CHEESE ............................21 CONDIMENTS BAKING JAM ..............................4 PIZZA SHELLS ...............................12 COFFEE AND TEA GOUDA.......................................21 AND JAMS TORTILLAS/WRAPS ......................12 HAVARTI.......................................22 BAKING MIXES ............................4 BAR MIXERS ................................17 CHUTNEY ....................................25 WRAPPERS ..................................12 JACK CHEESE .............................22 BAKING SUPPLIES .......................4 BITTERS .........................................17 GLAZES AND DEMI-GLAZES .......25 BROWNIES ..................................12 MASCARPONE ...........................22 COLORANTS ...............................4 CORDIAL ....................................17 KETCHUP .....................................25 CAKES ASSORTED ......................12 MISCELLANEOUS ........................22 CROISSANTS ...............................4 JUICE ...........................................17 MAYO ..........................................25 TARTS ...........................................13 MOUNTAIN STYLE ........................22 DÉCOR ........................................4 MISCELLANEOUS ........................17 MUSTARD ....................................25 COULIS ........................................13 MOZZARELLA ..............................22 EXTRACTS ....................................6 -

Report on the Composition of Prevalent Salt Varieties

Federal Department of Home Affairs FDHA Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office FSVO Nutrition Esther Infanger, Max Haldimann, Mai 2016 Report on the composition of prevalent salt varieties 071.1/2013/16500 \ COO.2101.102.7.405668 \ 000.00.61 Contents Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Zusammenfassung .................................................................................................................................. 4 Synthèse .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Sintesi .................................................................................................................................................... 6 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 7 2 Starting point............................................................................................................................... 7 3 Methods ...................................................................................................................................... 8 4 Results ........................................................................................................................................ 9 5 Discussion ............................................................................................................................... -

Epicurean Product Guide 2016 V6.Xlsx

Epicurean Product Listing 2016 800.934.6495 173 Thorn Hill Rd Warrendale, PA 15086 ** For the most up to date listing, please visit our website ** version 6, 9/27/16 EPICUREAN PRODUCT LISTING Condiments.........................................3 Miscellaneous......................................8 Oils & Vinegars................................1210 Syrups.............................................1513 Spices.............................................1715 Dried Mushrooms............................2321 Dried Fruits & Nuts..........................2422 Breads and Crackers.......................2724 Meats & Seafood.............................3027 Pasta Sauces and Noodles.............3330 Desserts..........................................3633 Chocolate........................................4037 Grains & Legumes...........................4340 Cheese, Dairy, & Eggs....................4542 Bar & Bakery.......................................47 Baking & Pastry...................................50 Appetizers...........................................61 CONDIMENTS Prod # Description Packaging UoM Special Order 06206 BASE BEEF NO MSG 4/5 LB CS 06207 BASE BEEF NO MSG 5 LB EA 06176 BASE BEEF NO MSG MINORS 12/1 LB CS X 06179 BASE CHICKEN NO MSG 1 LB EA 06201 BASE CHICKEN NO MSG 5 LB EA 06178 BASE CHICKEN NO MSG MINORS 12/1 LB CS 06200 BASE CHICKEN NO MSG MINORS 4/5 LB CS 06180 BASE CLAM NO MSG MINORS 6/1 LB CS 06181 BASE CLAM NO MSG MINORS 1# EA 06198 BASE CRAB NO MSG MINORS 6/1 LB CS 06199 BASE CRAB NO MSG MINORS 1# EA 06187 BASE ESPAGNOLE SAUCE -

PHOENIX Chefswarehouse.Com BAKING and PASTRY TORTILLAS/WRAPS

PRODUCT CATALOG PHOENIX chefswarehouse.com BAKING AND PASTRY TORTILLAS/WRAPS......................8 BEVERAGES, HAVARTI.......................................19 CONDIMENTS BAKING MIXES ............................4 WRAPPERS..................................8 COFFEE AND TEA JACK CHEESE .............................19 AND JAMS BROWNIES ..................................10 MASCARPONE ...........................19 BAKING SUPPLIES .......................4 BAR MIXERS ................................15 CHUTNEY ....................................24 CAKES ASSORTED ......................10 MISCELLANEOUS........................19 COLORANTS ...............................4 CORDIAL ....................................15 GLAZES AND DEMI-GLAZES .......24 TARTS ...........................................10 MOUNTAIN STYLE........................19 CROISSANTS ...............................4 JUICE ...........................................15 KETCHUP .....................................24 COULIS........................................10 MOZZARELLA..............................20 DÉCOR ........................................4 MISCELLANEOUS BEVERAGE ....15 MAYO ..........................................24 PUREE..........................................10 MUENSTER...................................20 EXTRACTS ....................................4 NECTAR .......................................15 MUSTARD ....................................24 ZEST..............................................10 PARMESAN .................................20 FILLING ........................................4 -

Cdcigpseldeguerandefleurde

APROSELA « Sel de Guérande » / « Fleur de sel de Guérande » 06/10/2010 – V5 Page 1/28 Indication G éographique Protégée - SEL DE GUERANDE – / - FLEUR DE SEL DE GUERANDE - Groupement demandeur Le Président du Conseil d’Administration A P R O S E L A Grégory PITART «Association pour la PRO motion du SEL Artisanal» 65, rue du Maréchal Juin 44420 LA TURBALLE Téléphone : 02 40 60 64 38 APROSELA « Sel de Guérande » / « Fleur de sel de Guérande » 06/10/2010 – V5 Page 2/28 S O M M A I R E I – LE GROUPEMENT DEMANDEUR 03 II – LE NOM DU PRODUIT 03 III – LE TYPE DE PRODUIT 03 IV – LA DESCRIPTION DU PRODUIT 03 IV.1 - Sel de Guérande 04 IV.2 - Fleur de sel de Guérande 04 IV.3 - Principales caractéristiques 04 V – LA DELIMITATION DE L’AIRE GEOGRAPHIQUE 05 V.1 - Délimitation de l’aire géographique de l’IGP 05 V.2 - Raisons du choix de l’aire géographique définie 07 VI – LES ELEMENTS PROUVANT QUE LE PRODUIT EST ORIGINAIRE DE L’AIRE DELIMITEE 08 VI.1 - Tableau de synthèse de la traçabilité 08 VI.2 - Schéma de traçabilité 09 VI.3 - Commentaires 10 VII - LA DESCRIPTION DE LA METHODE D’OBTENTION 12 VII.1 - Schéma de vie 12 VII.2 - Description du marais et fonctionnement d’une saline 14 VII.3 - La récolte du sel 16 VII.4 - Du stockage au conditionnement du sel et de la fleur de sel de Guérande 17 VIII – LES ELEMENTS JUSTIFIANT LE LIEN AVEC L’ORIGINE 18 VIII.1 – Spécificité de l’aire 18 VIII.2 – Spécificité des produits 20 VIII.3 – Lien causal 22 IX – REFERENCES CONCERNANT L’ORGANISME DE CONTRÔLE 24 X – REGLES DE L’ETIQUETAGE DU PRODUIT 24 XI - LES EXIGENCES -

Exotic Salts

Guide #1 - Exotic Salts Exotic Salts typically refer to naturally occurring mineral salts or Himalayan Pink Mineral Salt salts collected from bodies of water through evaporation. The Himalayan It’s one of the purest salts available on earth. Mined from deep in the Pink Salt is an example of mineral salt, while Fleur de Sel is an example Himalayan Mountains, this salt crystallized more than 200 million years of evaporated salt. Mineral salts are actually a type of sedimentary rock, ago and remains protected from modern-day pollution. It contains more than 84 trace minerals with none of the additives or aluminum com- and are mined. They often have high mineral content, and a unique set pounds found in refined salts. Uses: Grilling or roasting meat, fish or of flavors. Salts collected from bodies of water are done so through the chicken, and the coarse grain size can be used with a salt grinder. evaporation of rivers, oceans, ponds, etc. The flavor, texture, color, etc. of these salts will differ depending on the water type, the region where the Hawaiian Black Sea Salt water is collected, the time of year, and the evaporation process used. Characterized by a stunning black color and silky texture. Solar evapo- rated Pacific sea salt is combined with activated charcoal. The charcoal Alaea Hawaiian Sea Salt compliments the natural salt flavor and adds numerous health benefits. Harvested reddish Hawaiian clay enriches the salt with Iron Oxide. Savor Uses: Finishing, salads, meats, and seafood. a unique and pleasant flavor while roasting or grilling meats. It is the traditional and authentic seasoning for native Hawaiian dishes such as Kala Namak Indian Black Mineral Salt Kailua Pig, Hawaiian Jerky and Poke. -

Microbial Diversity of Culinary Salts by Galen Muske and Bonnie Baxter, Ph.D

Microbial Diversity of Culinary Salts By Galen Muske and Bonnie Baxter, Ph.D. Abstract Methods Results and Conclusion Extremophiles are exceptional microorganisms that live on this planet in extraordinarily harsh environments. One such extremophiles are Halophiles, salt-loving microorganisms that can survive in extreme salinity levels, and have been to found to survive inside salt crystals. We were curious is about the potential diversity of halophiles surviving in salts harvested from around the Figure 3: A mixed culture plate from primary cultures. A world. For this experiment various culinary salts were suspended in a 23 % NaCl growth media typical petri dish of the various species of halophilic microorganisms that grew from the original growth media. broth and allowed to grow for 4 weeks. Afterwards, the individual strains were isolated on 23 % These colonies were isolated and were grown separately in NaCl growth media agar plates. The colonies observed were visually diverse in color and margins. media broth before DNA isolation. Individual colonies were grown in broth and DNA was extracted. PCR and sequencing were http://www.stylepinner.com/quadrant-technique-streak- plate/cXVhZHJhbnQtdGVjaG5pcXVlLXN0cmVhay1wbGF0Z utilized to compare the 16S rRNA gene in each species of bacteria or archaea. We will present Q/ Isolation: Individual Colonies (isolated species) were chosen from Cultures were then plated onto data on the microbial diversity of the salts that did have media cultures. These salts come from 1) the plates and inoculated in 23% 23 % MGM agar plates. They MGM broth. They were incubated at salt pearls from Lake Assal Djibouti, Africa; 2 Fleur De Sel Gris Sea Salt from France, Europe; 3) were incubated at 37degrees C 37degrees C for 2 weeks sea salt from Bali, Indonesia; and 4) salt collected from the lake bed of Great Salt Lake, Utah. -

A Grain of Salt

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU The Kemp Foundation's Teaching Honorees for Teaching Excellence Excellence Award Ceremony 7-27-2020 A Grain of Salt Timothy Rettich Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/teaching_excellence Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Rettich, Timothy, "A Grain of Salt" (2020). Honorees for Teaching Excellence. 53. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/teaching_excellence/53 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Kemp Award Address 2020 Timothy Rettich “A Grain of Salt” April 8! The theme of this talk was written with this date for Honors Convocation in mind. It was intended to be not only timely, but also somewhat light-hearted. The times have changed, but I decided to keep the same talk, thinking that light-heartedness, like toilet paper, is now in short supply. But by keeping the same talk you will note some anachronisms. Those of you playing along at home can keep track of how many temporal mistakes I make. -

Fleur De Sel with a Grain of Salt?

Fleur de Sel with a Grain of Salt? Jennifer Contreras Welcome to Dining Room Operations. All semester long you will be asked to exemplify professionalism. You will be expected to raise the bar, your standards, and push aside any “me-first” attitude that, so often, wrongly appears in many service-oriented businesses. Your classroom will consist of napkins and wine glasses, entrée forks and knives. Of course you will think “good” service can be explained through the tired cliché: the guest is always right, but you will soon learn this is more than just a convenient line to mutter whenever a McDonald’s cashier sasses you, or the Domino’s pizza delivery man takes more than thirty minutes to deliver. After all, what does “good” even mean? You are guaranteed to be tested and tried, forced out of any comfort zone you have. In order to become a successful hospitality professional, you will be introduced to new tastes and experiences, and for those who want it, the chance at honing your service skills. Personally, a fine dining experience was something I had never had prior to the Dining Room Operations class, let alone something I cared to provide for others. Undoubtedly, I understood the connection between service and the hospitality industry, but I thought fine dining was only for those that could afford it. The characteristics of fine dining seemed to go beyond excellent service and focus on excluding underprivileged members of society. This notion seemed to go against my definition of service. I struggled to accept that fine dining was something more than pampering the self-important and self-indulged. -

L'or Blanc Ou Le Sel Sous Toutes Ses Formes

Les Cahiers de l’Académie ─ OPUS XIV 25 — François BRISSE L’OR BLANC OU LE SEL SOUS TOUTES SES FORMES INTRODUCTION LE SEL, IL Y EN A PARTOUT Savez-vous ce qu’est l’or blanc ? L’eau de mer. Plus de 60% de la surface de la terre est recouverte L’or blanc, c’est ainsi que depuis longtemps déjà on de mers ou d’océans. L’eau de mer contient un mé- appelait le sel. En effet, pour les gouvernements de lange de sels (sel de cuisine ou halite ou chlorure de tous les régimes, le sel qui a été pendant longtemps sodium, ainsi que du chlorure de potassium ou sylvi- fortement taxé, était tout comme une mine d’or, une te, du chlorure de magnésium, du sulfate de sodium importante source de revenu. et bien d’autres en moindres quantités). Mais c’est le SEL qui y est présent avec le plus grand pourcenta- Pour le commun des mortels, c’est le sel ou le sel de ge. Grâce à la mer, l’humanité a à sa disposition une cuisine. source de sel inépuisable (illustrations #1 et #2). Pour les minéralogistes, c’est le sel gemme ou la halite. Pour les chimistes, c’est le chlorure de sodium. On associe au sel toutes sortes de qualificatifs : le gros sel, le sel fin, le sel de mer, le sel gemme, le sel gris, le sel de Guérande, la fleur de sel, etc. Illustration #1 : La mer à la Pointe du Raz en Bretagne, France (1946). Le sel est sûrement le plus commun des produits naturels. -

Biological Properties of Carotenoids Extracted from Halobacterium

Abbes et al. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2013, 13:255 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6882/13/255 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Biological properties of carotenoids extracted from Halobacterium halobium isolated from a Tunisian solar saltern Molka Abbes1,4,5, Houda Baati1, Sonda Guermazi2, Concetta Messina3, Andrea Santulli4, Neji Gharsallah5 and Emna Ammar1* Abstract Background: Bioactive molecules have received increasing attention due to their nutraceutical attributes and anticancer, antioxidant, antiproliferative and apoptosis-inducing properties. This study aimed to investigate the biological properties of carotenoids extracted from Archaea. Methods: Halophilic Archaea strains were isolated from the brine of a local crystallizer pond (TS7) of a solar saltern at Sfax, Tunisia. The most carotenoid-producing strain (M8) was investigated on heptoma cell line (HepG2), and its viability was assessed by the MTT-test. The cells were incubated with different sub-lethal extract rates, with carotenoid concentrations ranging from 0.2 to 1.5 μM. Antioxidant activity was evaluated through exposing the cells to sub-lethal extract concentrations for 24 hours and then to oxidative stress induced by 60 μM arachidonic acid and 50 μMH2O2. Results: Compared to non-treated cells, bacterial carotenoid extracts inhibited HepG2 cell viability (50%). A time and dose effect was observed, with cell viability undergoing a significant (P < 0.05) decrease with extract concentration. After exposure to oxidative stress, control cells underwent a significant (P < 0.05) decrease in viability as compared to the non-treated cells. Conclusions: The bacterial extracts under investigation were noted to exhibit the strongest free radical scavenging activity with high carotenoid concentrations.