A Grain of Salt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latest Press Release from Consensus Action on Salt and Health

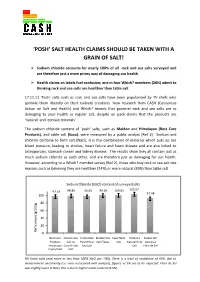

‘POSH’ SALT HEALTH CLAIMS SHOULD BE TAKEN WITH A GRAIN OF SALT! Sodium chloride accounts for nearly 100% of all rock and sea salts surveyed and are therefore just a more pricey way of damaging our health Health claims on labels fuel confusion; one in four Which? members (28%) admit to thinking rock and sea salts are healthier than table salt 17.11.11 ‘Posh’ salts such as rock and sea salts have been popularised by TV chefs who sprinkle them liberally on their culinary creations. New research from CASH (Consensus Action on Salt and Health) and Which? reveals that gourmet rock and sea salts are as damaging to your health as regular salt, despite on pack claims that the products are ‘natural’ and ‘contain minerals’. The sodium chloride content of ‘posh’ salts, such as Maldon and Himalayan (Best Care Products), and table salt (Saxa), were measured by a public analyst [Ref 1]. Sodium and chloride combine to form salt (NaCl), it is this combination of minerals which puts up our blood pressure, leading to strokes, heart failure and heart disease and are also linked to osteoporosis, stomach cancer and kidney disease. The results show they all contain just as much sodium chloride as each other, and are therefore just as damaging for our health. However, according to a Which? member survey [Ref 2], those who buy rock or sea salt cite reasons such as believing they are healthier (24%) or more natural (39%) than table salt. Sodium Chloride (NaCl) content of surveyed salts 98.86 96.65 99.50 100.65 103.57 97.19 91.48 100 80 60 40 20 NaCl contentNaCl (g/100g) 0 Best Care Cornish Sea Halen Mon Maldon Sea Saxa Table Tidman's Zauber der Products Salt Co Pure White Salt Flakes Salt Natural Rock Gewürze Himalayan Cornish Sea Sea Salt Salt Fleur de Sel Crystal Salt Salt NB Some salts total more or less than 100% NaCl per 100g. -

Sodium Chloride Or Rock Salt | Peters Chemical Company

MSDS Sheet – Sodium Chloride or Rock Salt | Peters Chemical Company Call Now - 1-973-427-8844 Home Contact Us Deicers Airport Runway Deicers Deicing Articles Lime & Limestone Misc. Print This Page MATERIAL SAFETY DATA SHEET Product Name: Sodium Chloride – Rock Salt – Halite EPA Reg. No: N/A 1. PRODUCT IDENTIFICATION Product Name: Sodium Chloride – Rock Salt UN/MA#: N/A DOT Hazard Class: N/A 2. INGREDIENTS & RECOMMENDED OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURE LIMITS TLV See Addendum 1 10 MG/M3 as nuisance dust. 3. PHYSICAL DATA Density: 40 – 70 lb/ft Boiling Point: N/A dry solid Melting Point: Partially decomposes at 12o F Vapor Pressure: N/A Vapor Density: N/A pH: 6-8 Solubility in Water: 100% Evaporation Rate: N/A Appearance and Odor: White Crystals and mild aromatic odor 4. FIRE AND EXPLOSION HAZARD DATA Flash Point: N/A Flammable Limits: N/A Fire Extinguishing Media: Considered non-combustible. Dry chemical. Foam, CO2, Water, Spray or Fog. Special Fire Fighting Procedures: Use self-contained breathing apparatus and full protective clothing. Fight fire from upwind side. Avoid run-off. Keep non-essential personnel away from immediate fire area, and out of any fall-out or run-off areas. Unusual Fire and Explosion Hazards: None 5. REACTIVITY DATA Stability: Stable Incompatibility: None Hazardous Decomposition or By-Products: None Conditions to Avoid: None Hazardous Polymerization: Will not occur http://www.peterschemical.com/sodium-chloride/msds-sheet-sodium-chloride-or-rock-salt/[1/8/2014 2:35:52 PM] MSDS Sheet – Sodium Chloride or Rock Salt | Peters Chemical Company 6. SPILL OR LEAK PROCEDURES Steps to be taken in case material is released: In case of release to the environment, report spills to the National Response Center 1-800-424-8802. -

1.5. Raman Spectroscopy

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Characteristic Raman Bands of Amino Acids and Halophiles as Biomarkers in Planetary Exploration Thesis How to cite: Rolfe, Samantha (2017). Characteristic Raman Bands of Amino Acids and Halophiles as Biomarkers in Planetary Exploration. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2016 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000c66a Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Characteristic Raman Bands of Amino Acids and Halophiles as Biomarkers in Planetary Exploration Samantha Melanie Rolfe MPhys (Hons), University of Leicester, 2010 September 2016 The Open University School of Physical Sciences A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE OPEN UNIVERSITY IN THE SUBJECT OF PLANETARY SCIENCES FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Acknowledgements To my parents, Mark and Melanie, and my brother, Alex, who have always supported and encouraged me to follow my dreams and overcome all and any obstacles to achieve them. To my grandparents, Anthony and Margery Wilson, Aubrey and Val Rolfe and Marjorie and Russell Whitmore, this work is dedicated to you. To Chris, my rock, without you I absolutely would not have been able to get through this process. -

Insights on Cadmium Removal by Bioremediation: the Case of Haloarchaea

Review Insights on Cadmium Removal by Bioremediation: The Case of Haloarchaea Mónica Vera-Bernal 1 and Rosa María Martínez-Espinosa 1,2,* 1 Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Division, Agrochemistry and Biochemistry Department, Faculty of Sciences, University of Alicante, Ap. 99, E-03080 Alicante, Spain; [email protected] 2 Multidisciplinary Institute for Environmental Studies “Ramón Margalef”, University of Alicante, Ap. 99, E-03080 Alicante, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-965903400 (ext. 1258; 8841) Abstract: Although heavy metals are naturally found in the environment as components of the earth’s crust, environmental pollution by these toxic elements has increased since the industrial revolution. Some of them can be considered essential, since they play regulatory roles in different biological processes; but the role of other heavy metals in living tissues is not clear, and once ingested they can accumulate in the organism for long periods of time causing adverse health effects. To mitigate this problem, different methods have been used to remove heavy metals from water and soil, such as chelation-based processes. However, techniques like bioremediation are leaving these conventional methodologies in the background for being more effective and eco-friendlier. Recently, different research lines have been promoted, in which several organisms have been used for bioremediation approaches. Within this context, the extremophilic microorganisms represent one of the best tools for the treatment of contaminated sites due to the biochemical and molecular properties they show. Furthermore, since it is estimated that 5% of industrial effluents are saline and hypersaline, halophilic microorganisms have been suggested as good candidates for bioremediation Citation: Vera-Bernal, M.; and treatment of this kind of samples. -

LAS VEGAS PRODUCT CATALOG INGREDIENTS Full Page Ad for FINE PASTRY 11”X 8.5”

PRODUCT CATALOG LAS VEGAS chefswarehouse.com BAKING AND PASTRY FROZEN/RTB BREAD ...................12 BEVERAGES, GOAT CHEESE ............................21 CONDIMENTS BAKING JAM ..............................4 PIZZA SHELLS ...............................12 COFFEE AND TEA GOUDA.......................................21 AND JAMS TORTILLAS/WRAPS ......................12 HAVARTI.......................................22 BAKING MIXES ............................4 BAR MIXERS ................................17 CHUTNEY ....................................25 WRAPPERS ..................................12 JACK CHEESE .............................22 BAKING SUPPLIES .......................4 BITTERS .........................................17 GLAZES AND DEMI-GLAZES .......25 BROWNIES ..................................12 MASCARPONE ...........................22 COLORANTS ...............................4 CORDIAL ....................................17 KETCHUP .....................................25 CAKES ASSORTED ......................12 MISCELLANEOUS ........................22 CROISSANTS ...............................4 JUICE ...........................................17 MAYO ..........................................25 TARTS ...........................................13 MOUNTAIN STYLE ........................22 DÉCOR ........................................4 MISCELLANEOUS ........................17 MUSTARD ....................................25 COULIS ........................................13 MOZZARELLA ..............................22 EXTRACTS ....................................6 -

Report on the Composition of Prevalent Salt Varieties

Federal Department of Home Affairs FDHA Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office FSVO Nutrition Esther Infanger, Max Haldimann, Mai 2016 Report on the composition of prevalent salt varieties 071.1/2013/16500 \ COO.2101.102.7.405668 \ 000.00.61 Contents Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Zusammenfassung .................................................................................................................................. 4 Synthèse .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Sintesi .................................................................................................................................................... 6 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 7 2 Starting point............................................................................................................................... 7 3 Methods ...................................................................................................................................... 8 4 Results ........................................................................................................................................ 9 5 Discussion ............................................................................................................................... -

Life at Low Water Activity

Published online 12 July 2004 Life at low water activity W. D. Grant Department of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, University of Leicester, Maurice Shock Building, University Road, Leicester LE1 9HN, UK ([email protected]) Two major types of environment provide habitats for the most xerophilic organisms known: foods pre- served by some form of dehydration or enhanced sugar levels, and hypersaline sites where water availability is limited by a high concentration of salts (usually NaCl). These environments are essentially microbial habitats, with high-sugar foods being dominated by xerophilic (sometimes called osmophilic) filamentous fungi and yeasts, some of which are capable of growth at a water activity (aw) of 0.61, the lowest aw value for growth recorded to date. By contrast, high-salt environments are almost exclusively populated by prokaryotes, notably the haloarchaea, capable of growing in saturated NaCl (aw 0.75). Different strategies are employed for combating the osmotic stress imposed by high levels of solutes in the environment. Eukaryotes and most prokaryotes synthesize or accumulate organic so-called ‘compatible solutes’ (osmolytes) that have counterbalancing osmotic potential. A restricted range of bacteria and the haloar- chaea counterbalance osmotic stress imposed by NaCl by accumulating equivalent amounts of KCl. Haloarchaea become entrapped and survive for long periods inside halite (NaCl) crystals. They are also found in ancient subterranean halite (NaCl) deposits, leading to speculation about survival over geological time periods. Keywords: xerophiles; halophiles; haloarchaea; hypersaline lakes; osmoadaptation; microbial longevity 1. INTRODUCTION aw = P/P0 = n1/n1 ϩ n2, There are two major types of environment in which water where n is moles of solvent (water); n is moles of solute; availability can become limiting for an organism. -

Epicurean Product Guide 2016 V6.Xlsx

Epicurean Product Listing 2016 800.934.6495 173 Thorn Hill Rd Warrendale, PA 15086 ** For the most up to date listing, please visit our website ** version 6, 9/27/16 EPICUREAN PRODUCT LISTING Condiments.........................................3 Miscellaneous......................................8 Oils & Vinegars................................1210 Syrups.............................................1513 Spices.............................................1715 Dried Mushrooms............................2321 Dried Fruits & Nuts..........................2422 Breads and Crackers.......................2724 Meats & Seafood.............................3027 Pasta Sauces and Noodles.............3330 Desserts..........................................3633 Chocolate........................................4037 Grains & Legumes...........................4340 Cheese, Dairy, & Eggs....................4542 Bar & Bakery.......................................47 Baking & Pastry...................................50 Appetizers...........................................61 CONDIMENTS Prod # Description Packaging UoM Special Order 06206 BASE BEEF NO MSG 4/5 LB CS 06207 BASE BEEF NO MSG 5 LB EA 06176 BASE BEEF NO MSG MINORS 12/1 LB CS X 06179 BASE CHICKEN NO MSG 1 LB EA 06201 BASE CHICKEN NO MSG 5 LB EA 06178 BASE CHICKEN NO MSG MINORS 12/1 LB CS 06200 BASE CHICKEN NO MSG MINORS 4/5 LB CS 06180 BASE CLAM NO MSG MINORS 6/1 LB CS 06181 BASE CLAM NO MSG MINORS 1# EA 06198 BASE CRAB NO MSG MINORS 6/1 LB CS 06199 BASE CRAB NO MSG MINORS 1# EA 06187 BASE ESPAGNOLE SAUCE -

PHOENIX Chefswarehouse.Com BAKING and PASTRY TORTILLAS/WRAPS

PRODUCT CATALOG PHOENIX chefswarehouse.com BAKING AND PASTRY TORTILLAS/WRAPS......................8 BEVERAGES, HAVARTI.......................................19 CONDIMENTS BAKING MIXES ............................4 WRAPPERS..................................8 COFFEE AND TEA JACK CHEESE .............................19 AND JAMS BROWNIES ..................................10 MASCARPONE ...........................19 BAKING SUPPLIES .......................4 BAR MIXERS ................................15 CHUTNEY ....................................24 CAKES ASSORTED ......................10 MISCELLANEOUS........................19 COLORANTS ...............................4 CORDIAL ....................................15 GLAZES AND DEMI-GLAZES .......24 TARTS ...........................................10 MOUNTAIN STYLE........................19 CROISSANTS ...............................4 JUICE ...........................................15 KETCHUP .....................................24 COULIS........................................10 MOZZARELLA..............................20 DÉCOR ........................................4 MISCELLANEOUS BEVERAGE ....15 MAYO ..........................................24 PUREE..........................................10 MUENSTER...................................20 EXTRACTS ....................................4 NECTAR .......................................15 MUSTARD ....................................24 ZEST..............................................10 PARMESAN .................................20 FILLING ........................................4 -

Final Feasibility and Cost Analysis Findings and Recommendations Report

Final FEASIBILITY AND COST ANALYSIS FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATION REPORT PARADOX VALLEY UNIT BYPRODUCTS DISPOSAL STUDY Submitted to: Wastren Advantage, Inc. 1571 Shyville Road Piketon, Ohio 45661 Submitted by: Amec Foster Wheeler Environment & Infrastructure, Inc. San Diego, California January 2017 Amec Foster Wheeler Project No. 1655500023 ©2016 Amec Foster Wheeler. All Rights Reserved. January 2017 Dave Sablosky Wastren Advantage, Inc. 1571 Shyville Road Piketon, Ohio 45661 Re: Final Feasibility, Cost Analysis, Findings, and Recommendation Report for Paradox Valley Unit Byproducts Disposal Study Dear Dave: The report included here satisfies the deliverable for the Paradox Valley Unit Evaporation Ponds Study 3: Final Feasibility, Cost Analysis, Findings, and Recommendations for Byproducts Disposal Report. As agreed with you and with Reclamation, this is a single combined report for the Byproducts Disposal Study that includes all elements anticipated from the Feasibility and Cost Analysis study, and the Findings and Recommendations report. This is a final version including all the information collected for Study 3 combined into a single report. It also includes the responses to the final comment matrix submitted by Reclamation. If you have any questions or concerns regarding this report, please contact Carla Scheidlinger at 858-300-4311 or by email at [email protected]. Respectfully submitted, Amec Foster Wheeler Environment & Infrastructure, Inc. Carla Scheidlinger Project Manager Amec Foster Wheeler Environment & Infrastructure, Inc. 9210 Sky Park Court, Suite 200 San Diego, California Tel: (858) 300-4300 Fax: (858) 300-4301 www.amecfw.com Wastren Advantage, Inc. Final Combined Findings and Recommendation Report Paradox Valley Unit Byproducts Disposal Study Amec Foster Wheeler Project No. -

SPR-691: Development of ADOT Application Rate Guidelines For

e SPR 691 OCTOBER 2015 Development of ADOT Application Rate Guidelines for Winter Storm Management of Chemical Additives through an Ambient Monitoring System Arizona Department of Transportation Research Center Development of ADOT Application Rate Guidelines for Winter Storm Management of Chemical Additives through an Ambient Monitoring System SPR‐691 October 2015 Prepared by: Ed Latimer, Richard Bansberg, Scott Hershberger, Theresa Price, Don Thorstenson, and Phil Ryder AMEC Environmental & Infrastructure 4600 E. Washington St., Suite 600 Phoenix, AZ 85034 Published by: Arizona Department of Transportation 206 S. 17th Ave. Phoenix, AZ 85007 In cooperation with U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration Disclaimer This report was funded in part through grants from the Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data, and for the use or adaptation of previously published material, presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Arizona Department of Transportation or the Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. Trade or manufacturers’ names that may appear herein are cited only because they are considered essential to the objectives of the report. The U.S. government and the State of Arizona do not endorse products or manufacturers. Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FHWA‐AZ‐15‐691 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Development of ADOT Application Rate Guidelines for Winter Storm October 2015 Management of Chemical Additives through an Ambient Monitoring 6. -

The Salt Smugglers Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE SALT SMUGGLERS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gerard De Nerval | 147 pages | 04 Mar 2010 | ARCHIPELAGO BOOKS | 9780980033069 | English | New York, United States The Salt Smugglers PDF Book There is not a day when they fight Community Reviews. To add more to the tongue-in-cheek pity, he can't write historical novels too, which would seem a shame, because Angelique's love life and the Abbe de Bucquoy's escapes from prison read very much like adventurous stories. There were a lot of complaints on the way warehouses had been located: people had to go through long and difficult trips, since they had to purchase at specific warehouse that they were assigned to. Learn More in these related Britannica articles:. Browse Index Authors Keywords Places. Feb 19, Maazah rated it it was amazing. More Details Refresh and try again. The salt tax was finally abolished in October by the Interim Government of India, just ten months before India gained independence. There were also complaints about the bad will of gabelle officers, especially that they were slow in their work, letting the poor tax payers waiting in the open air whatever the weather might be. Made by Hubert Proal. Ryan rated it it was amazing Jul 28, However, impatient to cross, it does not await the answer and embarks on its ship in In , they received from them eighty-five and all were of good service. During the first years of this experiment, the Canadian authorities overflow of enthusiasm. In the facts the war of succession of Austria put an end at the deportation of the salt-smugglers in Canada.