Volga German Dialects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landeszentrale Für Politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, Director: Lothar Frick 6Th Fully Revised Edition, Stuttgart 2008

BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG A Portrait of the German Southwest 6th fully revised edition 2008 Publishing details Reinhold Weber and Iris Häuser (editors): Baden-Württemberg – A Portrait of the German Southwest, published by the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, Director: Lothar Frick 6th fully revised edition, Stuttgart 2008. Stafflenbergstraße 38 Co-authors: 70184 Stuttgart Hans-Georg Wehling www.lpb-bw.de Dorothea Urban Please send orders to: Konrad Pflug Fax: +49 (0)711 / 164099-77 Oliver Turecek [email protected] Editorial deadline: 1 July, 2008 Design: Studio für Mediendesign, Rottenburg am Neckar, Many thanks to: www.8421medien.de Printed by: PFITZER Druck und Medien e. K., Renningen, www.pfitzer.de Landesvermessungsamt Title photo: Manfred Grohe, Kirchentellinsfurt Baden-Württemberg Translation: proverb oHG, Stuttgart, www.proverb.de EDITORIAL Baden-Württemberg is an international state – The publication is intended for a broad pub- in many respects: it has mutual political, lic: schoolchildren, trainees and students, em- economic and cultural ties to various regions ployed persons, people involved in society and around the world. Millions of guests visit our politics, visitors and guests to our state – in state every year – schoolchildren, students, short, for anyone interested in Baden-Würt- businessmen, scientists, journalists and numer- temberg looking for concise, reliable informa- ous tourists. A key job of the State Agency for tion on the southwest of Germany. Civic Education (Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, LpB) is to inform Our thanks go out to everyone who has made people about the history of as well as the poli- a special contribution to ensuring that this tics and society in Baden-Württemberg. -

Developing a Broadband Automatic Speech Recognition System for Afrikaans

INTERSPEECH 2011 Developing a broadband automatic speech recognition system for Afrikaans Febe de Wet1,2, Alta de Waal1 & Gerhard B van Huyssteen3 1Human Language Technology Competency Area, CSIR Meraka Institute, Pretoria, South Africa 2Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Stellenbosch University, South Africa 3Centre for Text Technology (CTexT), North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract the South African languages, followed by the local vernacular Afrikaans is one of the eleven official languages of South of South African English [3]. This position can be ascribed Africa. It is classified as an under-resourced language. No an- to various factors, including the fact that more linguistic ex- notated broadband speech corpora currently exist for Afrikaans. pertise and foundational work are available for Afrikaans and This article reports on the development of speech resources for South African English than for the other languages, the avail- Afrikaans, specifically a broadband speech corpus and an ex- ability of text (e.g. newspapers) and speech sources, the fact tended pronunciation dictionary. Baseline results for an ASR that Afrikaans is still somewhat used in the business domain and system that was built using these resources are also presented. in commercial environments (thereby increasing supply-and- In addition, the article suggests different strategies to exploit demand for Afrikaans-based technologies), and also the fact the close relationship between Afrikaans and Dutch for the pur- that Afrikaans could leverage on HLT developments for Dutch poses of technology development. (as a closely related language). Index Terms: Afrikaans, under-resourced languages, auto- Notwithstanding its profile as the most technologically de- matic speech recognition, speech resources veloped language in South Africa, Afrikaans can still be consid- ered an under-resourced language when compared to languages such as English, Spanish, Dutch or Japanese. -

Texas Alsatian

2017 Texas Alsatian Karen A. Roesch, Ph.D. Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis Indianapolis, Indiana, USA IUPUI ScholarWorks This is the author’s manuscript: This is a draft of a chapter that has been accepted for publication by Oxford University Press in the forthcoming book Varieties of German Worldwide edited by Hans Boas, Anna Deumert, Mark L. Louden, & Péter Maitz (with Hyoun-A Joo, B. Richard Page, Lara Schwarz, & Nora Hellmold Vosburg) due for publication in 2016. https://scholarworks.iupui.edu Texas Alsatian, Medina County, Texas 1 Introduction: Historical background The Alsatian dialect was transported to Texas in the early 1800s, when entrepreneur Henri Castro recruited colonists from the French Alsace to comply with the Republic of Texas’ stipulations for populating one of his land grants located just west of San Antonio. Castro’s colonization efforts succeeded in bringing 2,134 German-speaking colonists from 1843 – 1847 (Jordan 2004: 45-7; Weaver 1985:109) to his land grants in Texas, which resulted in the establishment of four colonies: Castroville (1844); Quihi (1845); Vandenburg (1846); D’Hanis (1847). Castroville was the first and most successful settlement and serves as the focus of this chapter, as it constitutes the largest concentration of Alsatian speakers. This chapter provides both a descriptive account of the ancestral language, Alsatian, and more specifically as spoken today, as well as a discussion of sociolinguistic and linguistic processes (e.g., use, shift, variation, regularization, etc.) observed and documented since 2007. The casual observer might conclude that the colonists Castro brought to Texas were not German-speaking at all, but French. -

German Dialects in Kansas and Missouri Scholarworks User Guide August, 2020

German Dialects in Kansas and Missouri ScholarWorks User Guide August, 2020 Table of Contents INTERVIEW METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................. 1 THE RECORDINGS ................................................................................................................................................. 2 THE SPEAKERS ...................................................................................................................................................... 2 KANSAS ....................................................................................................................................................................... 3 MISSOURI .................................................................................................................................................................... 4 THE QUESTIONNAIRES ......................................................................................................................................... 5 WENKER SENTENCES ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 KU QUESTIONNAIRE ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 REFERENCE MAPS FOR LOCATING POTENTIAL SPEAKERS ..................................................................................... -

Annual Report

2008 Annual Report Center for Language and Cognition Groningen Faculty of Arts, University of Groningen 2 Contents Foreword 5 Part One 1 Introduction 9 1.1 Institutional Embedding 9 1.2 Profile 9 2 CLCG in 2008 10 2.1 Structure 10 2.2 Director, Advisory Board, Coordinators 10 2.3 Assessment 11 2.4 Staffing 11 2.5 Finances: Travel and Material costs 12 2.6 Internationalization 12 2.7 Contract Research 13 3 Research Activities 14 3.1 Conferences, Cooperation, and Colloquia 14 3.1.1 TABU-day 2008 14 3.1.2 Groningen conferences 14 3.1.3 Conferences elsewhere 15 3.1.4 Visiting scholars 16 3.1.5 Linguistics Colloquium 17 3.1.6 Other lectures 18 3.2 CLCG-Publications 18 3.3 PhD Training Program 18 3.3.1 Graduate students 21 3.4 Postdocs 21 Part Two 4 Research Groups 25 4.1 Computational Linguistics 25 4.2 Discourse and Communication 39 4.3. Language and Literacy Development Across the Life Span 49 4.4. Language Variation and Language Change 61 4.5. Neurolinguistics 71 4.6. Syntax and Semantics 79 Part Three 5. Research Staff 2008 93 3 4 Foreword The Center for Language and Cognition, Groningen (CLCG) continued its research into 2008, making it an exciting place to work. On behalf of CLCG I am pleased to present the 2008 annual report. Highlights of this year s activities were the following. Five PhD theses were defended: • Starting a Sentence in Dutch: A corpus study of subject- and object-fronting (Gerlof Bouma). -

Of Trees and Birds : a Festschrift for Gisbert Fanselow

J. M. M. Brown | Andreas Schmidt | Marta Wierzba (Eds.) OF TREES AND BIRDS A Festschrift for Gisbert Fanselow Universitätsverlag Potsdam OF TREES AND BIRDS J. M. M. Brown | Andreas Schmidt | Marta Wierzba (Eds.) OF TREES AND BIRDS A Festschrift for Gisbert Fanselow Universitätsverlag Potsdam Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de/ abrufbar. Universitätsverlag Potsdam 2019 http://verlag.ub.uni-potsdam.de/ Am Neuen Palais 10, 14469 Potsdam Tel.: +49 (0)331 977 2533 / Fax: 2292 E-Mail: [email protected] Soweit nicht anders gekennzeichnet ist dieses Werk unter einem Creative Commons Lizenzvertrag lizenziert: Namensnennung 4.0 International Um die Bedingungen der Lizenz einzusehen, folgen Sie bitte dem Hyperlink: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de Umschlaggestaltung: Sarah Pertermann Druck: docupoint GmbH Magdeburg ISBN 978-3-86956-457-9 Zugleich online veröffentlicht auf dem Publikationsserver der Universität Potsdam: https://doi.org/10.25932/publishup-42654 https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-426542 Contents Preface ................................. xiii J.M. M. Brown, Andreas Schmidt, Marta Wierzba I Morphological branch 1 The instrumental -er suffix ..................... 3 Susan Olsen Bienenfresserortungsversuch: compounding with clause-embedding heads .................... 15 Barbara Stiebels Leben mit Paradoxien ........................ 27 Manfred Bierwisch Zur Analysierbarkeit adverbieller Konnektive ......... 37 Ilse Zimmermann Measuring lexical semantic variation using word embeddings ........................ 61 Damir Cavar II Syntactic branch 75 Intermediate reflexes of movement: A problem for TAG? .. 77 Doreen Georgi Towards a Fanselownian analysis of degree expressions ... 95 Julia Bacskai-Atkari v A form-function mismatch? The case of Greek deponents . -

Hunsrik-Xraywe.!A!New!Way!In!Lexicography!Of!The!German! Language!Island!In!Southern!Brazil!

Dialectologia.!Special-issue,-IV-(2013),!147+180.!! ISSN:!2013+2247! Received!4!June!2013.! Accepted!30!August!2013.! ! ! ! ! HUNSRIK-XRAYWE.!A!NEW!WAY!IN!LEXICOGRAPHY!OF!THE!GERMAN! LANGUAGE!ISLAND!IN!SOUTHERN!BRAZIL! Mateusz$MASELKO$ Austrian$Academy$of$Sciences,$Institute$of$Corpus$Linguistics$and$Text$Technology$ (ICLTT),$Research$Group$DINAMLEX$(Vienna,$Austria)$ [email protected]$ $ $ Abstract$$ Written$approaches$for$orally$traded$dialects$can$always$be$seen$controversial.$One$could$say$ that$there$are$as$many$forms$of$writing$a$dialect$as$there$are$speakers$of$that$dialect.$This$is$not$only$ true$ for$ the$ different$ dialectal$ varieties$ of$ German$ that$ exist$ in$ Europe,$ but$ also$ in$ dialect$ language$ islands$ on$ other$ continents$ such$ as$ the$ Riograndese$ Hunsrik$ in$ Brazil.$ For$ the$ standardization$ of$ a$ language$ variety$ there$ must$ be$ some$ determined,$ general$ norms$ regarding$ orthography$ and$ graphemics.!Equipe!Hunsrik$works$on$the$standardization,$expansion,$and$dissemination$of$the$German$ dialect$ variety$ spoken$ in$ Rio$ Grande$ do$ Sul$ (South$ Brazil).$ The$ main$ concerns$ of$ the$ project$ are$ the$ insertion$of$Riograndese$Hunsrik$as$official$community$language$of$Rio$Grande$do$Sul$that$is$also$taught$ at$school.$Therefore,$the$project$team$from$Santa$Maria$do$Herval$developed$a$writing$approach$that$is$ based$on$the$Portuguese$grapheme$inventory.$It$is$used$in$the$picture$dictionary! Meine!ëyerste!100! Hunsrik! wërter$ (2010).$ This$ article$ discusses$ the$ picture$ dictionary$ -

Yiddish and Relation to the German Dialects Bryan Witmore University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 6-30-2016 Yiddish and Relation To The German Dialects Bryan Witmore University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the German Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Witmore, B.(2016). Yiddish and Relation To The German Dialects. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ etd/3522 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. YIDDISH AND ITS RELATION TO THE GERMAN DIALECTS by Bryan Witmore Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina, 2006 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in German College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2016 Accepted by: Kurt Goblirsch, Director of Thesis Lara Ducate, Reader Lacy Ford, Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Bryan Witmore, 2016 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis project was made possible in large part by the German program at the University of South Carolina. The technical assistance that propelled this project was contributed by the staff at the Ted Mimms Foreign Language Learning Center. My family was decisive in keeping me physically functional and emotionally buoyant through the writing process. Many thanks to you all. iii ABSTRACT In an attempt to balance the complex, multi-component nature of Yiddish with its more homogenous speech community – Ashekenazic Jews –Yiddishists have proposed definitions for the Yiddish language that cannot be considered linguistic in nature. -

Hochdeutsch / High German

AVE GERMAN WILL TRAVEL sPRA DEUTSCH / GERMAN language: die Sprache, die Sprachen dialect: die Mundart, die Mundarten der Dialekt, die Dialekte slang: die Umgangssprache, die Umgangssprachen die Sondersprache, die Sondersprachen HOCHDEUTSCH / HIGH GERMAN High German or Hochdeutsch - The official language of Germany as promulgated in the schools. the press, the broadcast media. and specifically in the dictionary series called the Duden. gradation goes the broaaWest-East High German (Oberdeutsch):To the High Oberdeutsch Bavarian dialectal boundary through Upper German dialects belong Swabian Austria, Salzburg, the Styrian Enns valley, Alemannic (Schwabisch-Alemannisch), Alemannisth and Upper Carinthia. This boundary goes Bavarian (Bairisch), East Franconian - Allgauerisch back to the time of the first Bavarian land (Ostfrankisch) and South (Rhine) acquisition and follows approximately the Franconian (SGd(rhein)frankische). - Badisch outer boundary of East Carolingia and the - Elsassisch former Duchy of Austria. Swabian-Alemannic (Schwabisch Alemannisch): Includes Wuerttemberg - Schweizerdeutsch South Bavarian (Sudbairisch) South (W0rttemberg), Baden, German-speaking - Baseldeutsch Bavarian is spoken mostly in Styria. Alsace (Eisai!), Bavaria (Bayem) west ofthe Carinthia, and Tyrolia. Lech, and the German-speaking parts of - Berndeutsch Switzerland (Schweiz) and Vorarlberg. - Walliserdeutsch Salzburgish (Salzburgisch) Salzburgish is & Walserdeutsch an intermediate form between South and Swabian (Schwabisch) - Zurichdeutsch Middle Bavarian. Low Alemannic (Niederalemannisch) - Schwabisch Middle Bavarian (Mittelbairisch or - Vorarlbergerisch Donaubairisch): This dialect, also called High Alemannic (Hochalemannisch): High Bairisch Danube Bavarian, occupies most of the Alemannic is used in Switzerland. Bavarian region including the Danube and - Nordbairisch )he middle and lower Inn valleys and already Highest Alemannic (Hochstalemannisch, • Mittelbairisch m the early Middle Ages extended from the or Walserdeutsch): A form of High Lech to Bratislava (Pressburg). -

INTELLIGIBILITY of STANDARD GERMAN and LOW GERMAN to SPEAKERS of DUTCH Charlotte Gooskens1, Sebastian Kürschner2, Renée Van Be

INTELLIGIBILITY OF STANDARD GERMAN AND LOW GERMAN TO SPEAKERS OF DUTCH Charlotte Gooskens 1, Sebastian Kürschner 2, Renée van Bezooijen 1 1University of Groningen, The Netherlands 2 University of Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This paper reports on the intelligibility of spoken Low German and Standard German for speakers of Dutch. Two aspects are considered. First, the relative potential for intelligibility of the Low German variety of Bremen and the High German variety of Modern Standard German for speakers of Dutch is tested. Second, the question is raised whether Low German is understood more easily by subjects from the Dutch-German border area than subjects from other areas of the Netherlands. This is investigated empirically. The results show that in general Dutch people are better at understanding Standard German than the Low German variety, but that subjects from the border area are better at understanding Low German than subjects from other parts of the country. A larger amount of previous experience with the German standard variety than with Low German dialects could explain the first result, while proximity on the sound level could explain the second result. Key words Intelligibility, German, Low German, Dutch, Levenshtein distance, language contact 1. Introduction Dutch and German originate from the same branch of West Germanic. In the Middle Ages these neighbouring languages constituted a common dialect continuum. Only when linguistic standardisation came about in connection with nation building did the two languages evolve into separate social units. A High German variety spread out over the German language area and constitutes what is regarded as Modern Standard German today. -

Alsace and Its Language

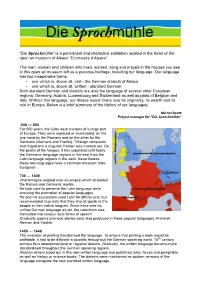

“Die Sproch mühle” is a permanent and interactive exhibition located in the heart of the open air museum of Alsace “Ecomusée d’Alsace”. The men, women and children who lived, worked, sang and prayed in the houses you see in this open air museum left us a precious heritage, including our language. Our language has two inseparable forms: • one which is, above all, oral - the German dialects of Alsace • one which is, above all, written - standard German Both standard German and dialects are also the language of several other European regions: Germany, Austria, Luxembourg and Switzerland as well as parts of Belgium and Italy. Without this language, our Alsace would finally lose its originality, its wealth and its role in Europe. Below is a brief summary of the history of our languages. Michel Bentz Project manager for “Die Sproch mühle“ -500 — 800 For 500 years, the Celts were masters of a large part of Europe. They were replaced or assimilated, on the one hand by the Romans and on the other by the Germans (Alemans and Franks). Through conquests and migrations a linguistic frontier was marked out. On the peaks of the Vosges, it has separated until today the Germanic language regions in the east from the Latin language regions in the west. Nevertheless, these two languages have a common ancestor: Indo- European. 700 — 1400 Charlemagne reigned over an empire which straddled the Roman and Germanic worlds. He took care to preserve the Latin language while ensuring the promotion of popular languages. He and his successors used Latin for official acts, but recommended to priests that they should speak to the people in their native tongues. -

Adverbial Reinforcement of Demonstratives in Dialectal German

Glossa a journal of general linguistics Adverbial reinforcement of COLLECTION: NEW PERSPECTIVES demonstratives in dialectal ON THE NP/DP DEBATE German RESEARCH PHILIPP RAUTH AUGUSTIN SPEYER *Author affiliations can be found in the back matter of this article ABSTRACT CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Philipp Rauth In the German dialects of Rhine and Moselle Franconian, demonstratives are Universität des Saarlandes, reinforced by locative adverbs do/lo ‘here/there’ in order to emphasize their deictic Germany strength. Interestingly, these adverbs can also appear in the intermediate position, i.e., [email protected] between the demonstrative and the noun (e.g. das do Bier ‘that there beer’), which is not possible in most other varieties of European German. Our questionnaire study and several written and oral sources suggest that reinforcement has become mandatory in KEYWORDS: demonstrative contexts. We analyze this grammaticalization process as reanalysis of demonstrative; reinforcer; do/lo from a lexical head to the head of a functional Index Phrase. We also show that a German; Rhine Franconian; functional DP-shell can better cope with this kind of syntactic change and with certain Moselle Franconian; Germanic; serialization facts concerning adjoined adjectives. Romance; dialectal German; grammaticalization; reanalysis; NP; DP; questionnaire TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Rauth, Philipp and Augustin Speyer. 2021. Adverbial reinforcement of demonstratives in dialectal German. Glossa: a journal of general linguistics 6(1): 4. 1–24. DOI: https://doi. org/10.5334/gjgl.1166 1 INTRODUCTION Rauth and Speyer 2 Glossa: a journal of In colloquial Standard German, the only difference between definite determiners (1a) and general linguistics DOI: 10.5334/gjgl.1166 demonstratives is emphatic stress in demonstrative contexts (1b).