The German Heritage of Kansas: an Introduction William D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pennsylvania Germans Move to Kansas

PENNSYLVANIA GERMANS MOVE TO KANSAS By GEORGE R. BEYER* rHE distinctive role wxhich the Pennsylvania Gertmans have TjIaved within the Keystone State since their arrival in thli late seve nteenith and eighteenth centuries is well known. As a group. of course, these people have never forsaken their original Amer- ican homeland, and vet individuals among them were longl conspic- llonlS in the movement of settlers to other parts of the countrys . This migration out of Pennsylvania began well before the Amer- ican Revolution, with Germans moving into Maryland as early as 1729 and into Virginia and the Carolinas in succeeding decades. Before the end of the eighteenth century, scattered settlements were planted in other parts of the East. As the years passed, Pennsylvania Germans also contrihuted notably to the peopling of the Middle and Far W\est. Considerable numbers of themil made their way into northern Ohio following the Revolutionary WVar, w ith some continuing on into Indiana. These states as well as Illinois received particularly large numbers of Pennsyl vania Ge"- uanl immigrants Luring the early part of the nineteenth century as did Iowa and Kansas in the several decades prior to 1890. Two other states, Oklahoma and California, attracted later settlers.' Although the immigration of Pennsylvania Germans did not occur as early in Kansas as it did in some states to the east, the story of the Kansas immigration is all extremely interesting one. MAIr. Beyer is an Assistant Archivist at the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission's Division of Public Records. This article is based on a master's thesis completed by the author at Cornell University in 1961, as well as on additional research conducted subsequently. -

Scottish Naming Customs Craig L

Scottish Naming Customs Craig L. Foster AG® [email protected] Origins of Scottish Surnames Surnames are said to have begun to be used by Scottish nobility at the direction of King Malcolm Ceannmor in about 1061. William L. Kirk, Jr. “Introduction to the Derivation of Scottish Surnames,” Clan Macrae (1992), http://www.clanmacrae.ca/documents/names.htm “In some Highland areas, though, fixed surnames did not become the norm until the 18th century, and in parts of the Northern Isles until the 19th century.” “Surnames,” ScotlandsPeople, https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/guides/surnames Types of Scottish Surnames Location-Based Surnames Some people were named for localities. For example, the surname “Murray from the lands of Moray, and Ogilvie, which, according to Black, derives from the barony of Ogilvie in the parish of Glamis, Angus. Tenants might in turn assume, or be given, the name of their landlord, despite having no kinship with him.” Sometimes surnames referred to a specific topographical feature of the landscape such as a river, a loch, a hill, etc. Some examples might include: Names that contain 'kirk' (as in Kirkland, or Selkirk) which means 'church' in Gaelic; 'Muir' or names that contain it (means 'moor' in Gaelic); A name which has 'Barr' in it (this means 'hilltop' in Gaelic). “Surnames,” ScotlandsPeople, https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/guides/surnames Occupational Surnames A significant amount of surnames come from occupations. So a smith became known as Smith or Gow (Gaelic for smith), a tailor became Tailor/Taylor, a baker was Baxter, a weaver was Webster, etc. “Surnames,”ScotlandsPeople, https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/guides/surnames Descriptive Surnames “Nicknames were 'descriptional' ie. -

Texas Alsatian

2017 Texas Alsatian Karen A. Roesch, Ph.D. Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis Indianapolis, Indiana, USA IUPUI ScholarWorks This is the author’s manuscript: This is a draft of a chapter that has been accepted for publication by Oxford University Press in the forthcoming book Varieties of German Worldwide edited by Hans Boas, Anna Deumert, Mark L. Louden, & Péter Maitz (with Hyoun-A Joo, B. Richard Page, Lara Schwarz, & Nora Hellmold Vosburg) due for publication in 2016. https://scholarworks.iupui.edu Texas Alsatian, Medina County, Texas 1 Introduction: Historical background The Alsatian dialect was transported to Texas in the early 1800s, when entrepreneur Henri Castro recruited colonists from the French Alsace to comply with the Republic of Texas’ stipulations for populating one of his land grants located just west of San Antonio. Castro’s colonization efforts succeeded in bringing 2,134 German-speaking colonists from 1843 – 1847 (Jordan 2004: 45-7; Weaver 1985:109) to his land grants in Texas, which resulted in the establishment of four colonies: Castroville (1844); Quihi (1845); Vandenburg (1846); D’Hanis (1847). Castroville was the first and most successful settlement and serves as the focus of this chapter, as it constitutes the largest concentration of Alsatian speakers. This chapter provides both a descriptive account of the ancestral language, Alsatian, and more specifically as spoken today, as well as a discussion of sociolinguistic and linguistic processes (e.g., use, shift, variation, regularization, etc.) observed and documented since 2007. The casual observer might conclude that the colonists Castro brought to Texas were not German-speaking at all, but French. -

German Dialects in Kansas and Missouri Scholarworks User Guide August, 2020

German Dialects in Kansas and Missouri ScholarWorks User Guide August, 2020 Table of Contents INTERVIEW METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................. 1 THE RECORDINGS ................................................................................................................................................. 2 THE SPEAKERS ...................................................................................................................................................... 2 KANSAS ....................................................................................................................................................................... 3 MISSOURI .................................................................................................................................................................... 4 THE QUESTIONNAIRES ......................................................................................................................................... 5 WENKER SENTENCES ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 KU QUESTIONNAIRE ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 REFERENCE MAPS FOR LOCATING POTENTIAL SPEAKERS ..................................................................................... -

British Family Names

cs 25o/ £22, Cornrll IBniwwitg |fta*g BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Hcnrti W~ Sage 1891 A.+.xas.Q7- B^llll^_ DATE DUE ,•-? AUG 1 5 1944 !Hak 1 3 1^46 Dec? '47T Jan 5' 48 ft e Univeral, CS2501 .B23 " v Llb«"y Brit mii!Sm?nS,£& ori8'" and m 3 1924 olin 029 805 771 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029805771 BRITISH FAMILY NAMES. : BRITISH FAMILY NAMES ftbetr ©riain ano fIDeaning, Lists of Scandinavian, Frisian, Anglo-Saxon, and Norman Names. HENRY BARBER, M.D. (Clerk), "*• AUTHOR OF : ' FURNESS AND CARTMEL NOTES,' THE CISTERCIAN ABBEY OF MAULBRONN,' ( SOME QUEER NAMES,' ' THE SHRINE OF ST. BONIFACE AT FULDA,' 'POPULAR AMUSEMENTS IN GERMANY,' ETC. ' "What's in a name ? —Romeo and yuliet. ' I believe now, there is some secret power and virtue in a name.' Burton's Anatomy ofMelancholy. LONDON ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. 1894. 4136 CONTENTS. Preface - vii Books Consulted - ix Introduction i British Surnames - 3 nicknames 7 clan or tribal names 8 place-names - ii official names 12 trade names 12 christian names 1 foreign names 1 foundling names 1 Lists of Ancient Patronymics : old norse personal names 1 frisian personal and family names 3 names of persons entered in domesday book as HOLDING LANDS temp. KING ED. CONFR. 37 names of tenants in chief in domesday book 5 names of under-tenants of lands at the time of the domesday survey 56 Norman Names 66 Alphabetical List of British Surnames 78 Appendix 233 PREFACE. -

Hunsrik-Xraywe.!A!New!Way!In!Lexicography!Of!The!German! Language!Island!In!Southern!Brazil!

Dialectologia.!Special-issue,-IV-(2013),!147+180.!! ISSN:!2013+2247! Received!4!June!2013.! Accepted!30!August!2013.! ! ! ! ! HUNSRIK-XRAYWE.!A!NEW!WAY!IN!LEXICOGRAPHY!OF!THE!GERMAN! LANGUAGE!ISLAND!IN!SOUTHERN!BRAZIL! Mateusz$MASELKO$ Austrian$Academy$of$Sciences,$Institute$of$Corpus$Linguistics$and$Text$Technology$ (ICLTT),$Research$Group$DINAMLEX$(Vienna,$Austria)$ [email protected]$ $ $ Abstract$$ Written$approaches$for$orally$traded$dialects$can$always$be$seen$controversial.$One$could$say$ that$there$are$as$many$forms$of$writing$a$dialect$as$there$are$speakers$of$that$dialect.$This$is$not$only$ true$ for$ the$ different$ dialectal$ varieties$ of$ German$ that$ exist$ in$ Europe,$ but$ also$ in$ dialect$ language$ islands$ on$ other$ continents$ such$ as$ the$ Riograndese$ Hunsrik$ in$ Brazil.$ For$ the$ standardization$ of$ a$ language$ variety$ there$ must$ be$ some$ determined,$ general$ norms$ regarding$ orthography$ and$ graphemics.!Equipe!Hunsrik$works$on$the$standardization,$expansion,$and$dissemination$of$the$German$ dialect$ variety$ spoken$ in$ Rio$ Grande$ do$ Sul$ (South$ Brazil).$ The$ main$ concerns$ of$ the$ project$ are$ the$ insertion$of$Riograndese$Hunsrik$as$official$community$language$of$Rio$Grande$do$Sul$that$is$also$taught$ at$school.$Therefore,$the$project$team$from$Santa$Maria$do$Herval$developed$a$writing$approach$that$is$ based$on$the$Portuguese$grapheme$inventory.$It$is$used$in$the$picture$dictionary! Meine!ëyerste!100! Hunsrik! wërter$ (2010).$ This$ article$ discusses$ the$ picture$ dictionary$ -

Afrikaans FAMILY HISTORY LIBRARY" SALTLAKECITY, UTAH TMECHURCHOF JESUS CHRISTOF Latl'er-Qt.Y SAINTS

GENEALOGICAL WORD LIST ~ Afrikaans FAMILY HISTORY LIBRARY" SALTLAKECITY, UTAH TMECHURCHOF JESUS CHRISTOF LATl'ER-Qt.y SAINTS This list contains Afrikaans words with their English these compound words are included in this list. You translations. The words included here are those that will need to look up each part of the word separately. you are likely to find in genealogical sources. If the For example, Geboortedag is a combination of two word you are looking for is not on this list, please words, Geboorte (birth) and Dag (day). consult a Afrikaans-English dictionary. (See the "Additional Resources" section below.) Alphabetical Order Afrikaans is a Germanic language derived from Written Afrikaans uses a basic English alphabet several European languages, primarily Dutch. Many order. Most Afrikaans dictionaries and indexes as of the words resemble Dutch, Flemish, and German well as the Family History Library Catalog..... use the words. Consequently, the German Genealogical following alphabetical order: Word List (34067) and Dutch Genealogical Word List (31030) may also be useful to you. Some a b c* d e f g h i j k l m n Afrikaans records contain Latin words. See the opqrstuvwxyz Latin Genealogical Word List (34077). *The letter c was used in place-names and personal Afrikaans is spoken in South Africa and Namibia and names but not in general Afrikaans words until 1985. by many families who live in other countries in eastern and southern Africa, especially in Zimbabwe. Most The letters e, e, and 0 are also used in some early South African records are written in Dutch, while Afrikaans words. -

Yiddish and Relation to the German Dialects Bryan Witmore University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 6-30-2016 Yiddish and Relation To The German Dialects Bryan Witmore University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the German Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Witmore, B.(2016). Yiddish and Relation To The German Dialects. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ etd/3522 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. YIDDISH AND ITS RELATION TO THE GERMAN DIALECTS by Bryan Witmore Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina, 2006 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in German College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2016 Accepted by: Kurt Goblirsch, Director of Thesis Lara Ducate, Reader Lacy Ford, Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Bryan Witmore, 2016 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis project was made possible in large part by the German program at the University of South Carolina. The technical assistance that propelled this project was contributed by the staff at the Ted Mimms Foreign Language Learning Center. My family was decisive in keeping me physically functional and emotionally buoyant through the writing process. Many thanks to you all. iii ABSTRACT In an attempt to balance the complex, multi-component nature of Yiddish with its more homogenous speech community – Ashekenazic Jews –Yiddishists have proposed definitions for the Yiddish language that cannot be considered linguistic in nature. -

INTELLIGIBILITY of STANDARD GERMAN and LOW GERMAN to SPEAKERS of DUTCH Charlotte Gooskens1, Sebastian Kürschner2, Renée Van Be

INTELLIGIBILITY OF STANDARD GERMAN AND LOW GERMAN TO SPEAKERS OF DUTCH Charlotte Gooskens 1, Sebastian Kürschner 2, Renée van Bezooijen 1 1University of Groningen, The Netherlands 2 University of Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This paper reports on the intelligibility of spoken Low German and Standard German for speakers of Dutch. Two aspects are considered. First, the relative potential for intelligibility of the Low German variety of Bremen and the High German variety of Modern Standard German for speakers of Dutch is tested. Second, the question is raised whether Low German is understood more easily by subjects from the Dutch-German border area than subjects from other areas of the Netherlands. This is investigated empirically. The results show that in general Dutch people are better at understanding Standard German than the Low German variety, but that subjects from the border area are better at understanding Low German than subjects from other parts of the country. A larger amount of previous experience with the German standard variety than with Low German dialects could explain the first result, while proximity on the sound level could explain the second result. Key words Intelligibility, German, Low German, Dutch, Levenshtein distance, language contact 1. Introduction Dutch and German originate from the same branch of West Germanic. In the Middle Ages these neighbouring languages constituted a common dialect continuum. Only when linguistic standardisation came about in connection with nation building did the two languages evolve into separate social units. A High German variety spread out over the German language area and constitutes what is regarded as Modern Standard German today. -

Alsace and Its Language

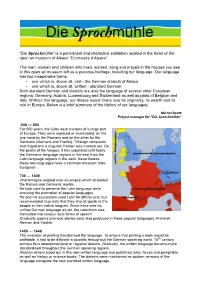

“Die Sproch mühle” is a permanent and interactive exhibition located in the heart of the open air museum of Alsace “Ecomusée d’Alsace”. The men, women and children who lived, worked, sang and prayed in the houses you see in this open air museum left us a precious heritage, including our language. Our language has two inseparable forms: • one which is, above all, oral - the German dialects of Alsace • one which is, above all, written - standard German Both standard German and dialects are also the language of several other European regions: Germany, Austria, Luxembourg and Switzerland as well as parts of Belgium and Italy. Without this language, our Alsace would finally lose its originality, its wealth and its role in Europe. Below is a brief summary of the history of our languages. Michel Bentz Project manager for “Die Sproch mühle“ -500 — 800 For 500 years, the Celts were masters of a large part of Europe. They were replaced or assimilated, on the one hand by the Romans and on the other by the Germans (Alemans and Franks). Through conquests and migrations a linguistic frontier was marked out. On the peaks of the Vosges, it has separated until today the Germanic language regions in the east from the Latin language regions in the west. Nevertheless, these two languages have a common ancestor: Indo- European. 700 — 1400 Charlemagne reigned over an empire which straddled the Roman and Germanic worlds. He took care to preserve the Latin language while ensuring the promotion of popular languages. He and his successors used Latin for official acts, but recommended to priests that they should speak to the people in their native tongues. -

Vowel Change in English and German: a Comparative Analysis

Vowel change in English and German: a comparative analysis Miriam Calvo Fernández Degree in English Studies Academic Year: 2017/2018 Supervisor: Reinhard Bruno Stempel Department of English and German Philology and Translation Abstract English and German descend from the same parent language: West-Germanic, from which other languages, such as Dutch, Afrikaans, Flemish, or Frisian come as well. These would, therefore, be called “sister” languages, since they share a number of features in syntax, morphology or phonology, among others. The history of English and German as sister languages dates back to the Late antiquity, when they were dialects of a Proto-West-Germanic language. After their split, more than 1,400 years ago, they developed their own language systems, which were almost identical at their earlier stages. However, this is not the case anymore, as can be seen in their current vowel systems: the German vowel system is composed of 23 monophthongs and 8 diphthongs, while that of English has only 12 monophthongs and 8 diphthongs. The present paper analyses how the English and German vowels have gradually changed over time in an attempt to understand the differences and similarities found in their current vowel systems. In order to do so, I explain in detail the previous stages through which both English and German went, giving special attention to the vowel changes from a phonological perspective. Not only do I describe such processes, but I also contrast the paths both languages took, which is key to understand all the differences and similarities present in modern English and German. The analysis shows that one of the main reasons for the differences between modern German and English is to be found in all the languages English has come into contact with in the course of its history, which have exerted a significant influence on its vowel system, making it simpler than that of German. -

Pennsylvania Germans Simon J

Pennsylvania Germans Simon J. Bronner, Joshua R. Brown Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Bronner, Simon J. and Joshua R. Brown. Pennsylvania Germans: An Interpretive Encyclopedia. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017. Project MUSE., <a href=" https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/49568 Access provided at 3 Jan 2020 23:09 GMT from University of Wisconsin @ Madison UPart 2 Culture and Society This page intentionally left blank U4 The Pennsylvania German Language mark l. louden The story of the Pennsylvania German language is an unusual one across the sociolinguistic landscape of North America. Worldwide, languages spo- ken today by minority populations are in a critical situation, with most in serious danger of becoming extinct. Indeed, of the approximately 7,000 lan- guages spoken across the globe, at least half are predicted to lose their native speakers by the turn of the century. Yet Pennsylvania German, spoken by a minuscule 0.08 percent of the U.S. population, is exceptional. Despite the fact that it is an oral vernacular language lacking in any offi cial recognition or support, it thrives today in the United States of America, the heartland of the world’s dominant engine of economic and cultural globalization, whose majority language, English, has become the international lingua franca. And although the linguistic roots of Pennsylvania German lie in central Europe, its speakers have always viewed themselves every bit as American as their English- monolingual neighbors. Pennsylvania Dutch or Pennsylvania German? Language or Dialect? Pennsylvania German (PG) is a North American language that developed during the eighteenth century in colonial Pennsylvania as the result of the immigration of several thousand speakers from mainly southwestern German- speaking Europe, especially the linguistic and cultural area known as the Palatinate (German Pfalz).