Beyond Informed Consent Zulfiqar A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jus Cogens As a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr

Penn State International Law Review Volume 29 Article 2 Number 2 Penn State International Law Review 9-1-2010 Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Petsche, Dr. Markus (2010) "Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 29: No. 2, Article 2. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol29/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Articles I Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche* Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .............................................. 235 I. THE INAPPROPRIATENESS OF CHARACTERIZING JUS COGENS AS A RULE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE LIMITED RELEVANCE OF JUS COGENS FOR THE PRACTICE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW...................................238 A. FundamentalConceptual and Theoretical Flaws ofJus Cogens .................................... 238 1. Origins of Jus Cogens. .................. ..... 238 2. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking Substance........ 242 3. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Procedure for Its Determination. ............ ......... .......... 243 4. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Proper Theoretical Basis.......................... 245 B. The Limited Relevance of Jus Cogens for the Law of Treaties: Rare and Unsuccessful Reliance on Jus * DEA (Paris 1); LL.M. (NYU); Ph.D. -

Indigenous and Tribal People's Rights Over Their Ancestral Lands

INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 56/09 30 December 2009 Original: Spanish INDIGENOUS AND TRIBAL PEOPLES’ RIGHTS OVER THEIR ANCESTRAL LANDS AND NATURAL RESOURCES Norms and Jurisprudence of the Inter‐American Human Rights System 2010 Internet: http://www.cidh.org E‐mail: [email protected] OAS Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data Derechos de los pueblos indígenas y tribales sobre sus tierras ancestrales y recursos naturales: Normas y jurisprudencia del sistema interamericano de derechos humanos = Indigenous and tribal people’s rights over their ancestral lands and natural resources: Norms and jurisprudence of the Inter‐American human rights system / [Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights.] p. ; cm. (OEA documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L)(OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978‐0‐8270‐5580‐3 1. Human rights‐‐America. 2. Indigenous peoples‐‐Civil rights‐‐America. 3. Indigenous peoples‐‐Land tenure‐‐America. 4. Indigenous peoples‐‐Legal status, laws, etc.‐‐America. 5. Natural resources‐‐Law and legislation‐‐America. I. Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. II Series. III. Series. OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.56/09 Document published thanks to the financial support of Denmark and Spain Positions herein expressed are those of the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights and do not reflect the views of Denmark or Spain Approved by the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights on December 30, 2009 INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS MEMBERS Luz Patricia Mejía Guerrero Víctor E. Abramovich Felipe González Sir Clare Kamau Roberts Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro Florentín Meléndez Paolo G. Carozza ****** Executive Secretary: Santiago A. -

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don't Have Sex Without Them

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don’t Have Sex Without Them A Lesson Plan from Rights, Respect, Responsibility: A K-12 Curriculum Fostering responsibility by respecting young people’s rights to honest sexuality education. ADVANCE PREPARATION FOR LESSON: NSES ALIGNMENT: • Download the YouTube video on consent, “2 Minutes Will By the end of 12th grade, Change the Way You Think About Consent,” at https://www. students will be able to: youtube.com/watch?v=laMtr-rUEmY. HR.12.CC.3 – Define sexual consent and explain its • Also download the trailer for Pitch Perfect 2 - The Ellen Show implications for sexual decision- version (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBwOYQd21TY), making. queuing it up to play a brief clip between 2:10 and 2:27. PS.12.CC.3 – Explain why using tricks, threats or coercion in • If you cannot download and save these to your desktop in relationships is wrong. advance, talk with your school’s IT person to ensure you have HR.12.INF.2 – Analyze factors, internet access to that link during class. including alcohol and other substances, that can affect the • Print out the skit scenarios and cut out each pair, making sure ability to give or perceive the the correct person 1 goes with the correct person 2. Determine provision of consent to sexual how many pairs there will be in your class and make several activity. copies of each scenario, enough for each pair to get one. TARGET GRADE: Grade 10 LEARNING OBJECTIVES: Lesson 1 By the end of this lesson, students will be able to: 1. -

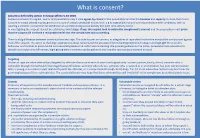

What Is Consent?

What is consent? Consent is defined by section 74 Sexual Offences Act 2003. Someone consents to vaginal, anal or oral penetration only if s/he agrees by choice to that penetration and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice. Consent to sexual activity may be given to one sort of sexual activity but not another, e.g.to vaginal but not anal sex or penetration with conditions, such as wearing a condom. Consent can be withdrawn at any time during sexual activity and each time activity occurs. In investigating the suspect, it must be established what steps, if any, the suspect took to obtain the complainant’s consent and the prosecution must prove that the suspect did not have a reasonable belief that the complainant was consenting. There is a big difference between consensual sex and rape. This aide focuses on consent, as allegations of rape often involve the word of the complainant against that of the suspect. The aim is to challenge assumptions about consent and the associated victim-blaming myths/stereotypes and highlight the suspect’s behaviour and motives to prove he did not reasonably believe the victim was consenting. We provide guidance to the police, prosecutors and advocates to identify and explain the differences, highlighting where evidence can be gathered and how the case can be presented in court. Targeting Victims of rape are often selected and targeted by offenders because of ease of access and opportunity - current partner, family, friend, someone who is vulnerable through mental health/ learning/physical difficulties, someone who sells sex, someone who is isolated or in an institution, has poor communication skills, is young, in a current or past relationship with the offender, or is compromised through drink/drugs. -

Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies

future internet Review Trust, but Verify: Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies Brian Pickering IT Innovation, Electronics and Computing, University of Southampton, University Road, Southampton SO17 1BJ, UK; [email protected] Abstract: To use technology or engage with research or medical treatment typically requires user consent: agreeing to terms of use with technology or services, or providing informed consent for research participation, for clinical trials and medical intervention, or as one legal basis for processing personal data. Introducing AI technologies, where explainability and trustworthiness are focus items for both government guidelines and responsible technologists, imposes additional challenges. Understanding enough of the technology to be able to make an informed decision, or consent, is essential but involves an acceptance of uncertain outcomes. Further, the contribution of AI- enabled technologies not least during the COVID-19 pandemic raises ethical concerns about the governance associated with their development and deployment. Using three typical scenarios— contact tracing, big data analytics and research during public emergencies—this paper explores a trust- based alternative to consent. Unlike existing consent-based mechanisms, this approach sees consent as a typical behavioural response to perceived contextual characteristics. Decisions to engage derive from the assumption that all relevant stakeholders including research participants will negotiate on an ongoing basis. Accepting dynamic negotiation between the main stakeholders as proposed here introduces a specifically socio–psychological perspective into the debate about human responses Citation: Pickering, B. Trust, but to artificial intelligence. This trust-based consent process leads to a set of recommendations for the Verify: Informed Consent, AI ethical use of advanced technologies as well as for the ethical review of applied research projects. -

Citizen Science: Framing the Public, Information Exchange, and Communication in Crowdsourced Science

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2014 Citizen Science: Framing the Public, Information Exchange, and Communication in Crowdsourced Science Todd Ernest Suomela University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Communication Commons, and the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Suomela, Todd Ernest, "Citizen Science: Framing the Public, Information Exchange, and Communication in Crowdsourced Science. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2014. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/2864 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Todd Ernest Suomela entitled "Citizen Science: Framing the Public, Information Exchange, and Communication in Crowdsourced Science." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Communication and Information. Suzie Allard, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Carol Tenopir, Mark Littmann, Harry Dahms Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Citizen Science: Framing the Public, Information Exchange, and Communication in Crowdsourced Science ADissertationPresentedforthe Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Todd Ernest Suomela August 2014 c by Todd Ernest Suomela, 2014 All Rights Reserved. -

Personal Autonomy and Informed Consent: Conceptual and Normative Analyses

Personal Autonomy and Informed Consent: Conceptual and Normative Analyses Jesper Ahlin Licentiate thesis in philosophy KTH Royal Institute of Technology Stockholm, «Ï; © «Ï; Ahlin All rights reserved. Ahlin, J. Personal Autonomy and Informed Consent:Conceptual and Normative Analyses Licentiate thesis KTH Royal Institute of Technology TOC ;Ê-Ï-;;-- TOO ÏE«-ÊÊtÏ Typeset by the author, with help from Jesper Jerkert, using LATEX and BTCTEX.Printed by Universitetsservice US-AB, Drottning Kristinas väg tB, ÏÏ Ê Stockholm. I know what I know Acknowledgments I am grateful to Barbro Fröding, Sven Ove Hansson, and Niklas Juth for their su- pervision of this thesis, and to Gert Helgesson for his many useful comments on an earlier dra. Also, I thank William Bülow, Jesper Jerkert,Björn Lundgren, Payam Moula, and Maria Nordström, among others, for support and stimulating discussions. My thanks are extended to the Higher seminar at the Division of Philosophy, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, the Higher seminar at the Centre for Healthcare Ethics, Karolinska Institutet, and the VR/FORTE research program for providing opportu- nities to discuss and develop these ideas. All errors and mistakes are of course my own. his research was supported by the Swedish Research Council (VR) and the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (FORTE), contract no. «Ï– «, for the project Addressing Ethical Obstacles to Person Centred Care. Stockholm,August «Ï; Jesper Ahlin Abstract his licentiate thesis is comprised of a “kappa” and two articles. he kappa includes an account of personal autonomy and informed consent, an explanation of how the concepts and articles relate to each other, and a summary in Swedish. -

Manufacturing Consent Thirty Years Later

ANOTHER THIRTY YEARS1 Michael Burawoy It is now exactly 30 years since I began working at Allied Corporation, which in turn was 30 years after the great Chicago ethnographer, Donald Roy, began working there in 1944. I recently returned to my old stomping ground to see what had become of the engine division of Allis Chalmers – I can now reveal the company’s real name. The physical plant is still there in the town of Harvey, south of Chicago. Its grounds are overgrown with weeds, its buildings are dilapidated. It has a new owner. Allis Chalmers, then the third biggest corporation in the production of agricultural equipment after Caterpillar and John Deere, entered dire financial straights and was bought out by K-H-Deutz AG of Germany in 1985. The engine division in Harvey also shut down in 1985. Soon, thereafter, it became the warehouse of a local manufacturer of steel tubes – Allied Tubes. Thus, in yet another quirk of sociological serendipity the alias that I gave Allis Chalmers turned out to be the actual name of the company that bought it up! Even more interesting, in 1987, Allied Tubes was taken over by Tyco -- the scandal-fraught international conglomerate. In the last year Tyco’s two top executives have made headline news, charged with securities fraud, tax evasion and looting hundreds of millions of dollars from the conglomerate. Warehousing, conglomeration and corporate looting well capture the fall out of the Reagan era that began in 1980, five years after I left Allis. South Chicago had been 1 To appear as a special preface to the Chinese edition of Manufacturing Consent. -

What Is Consent?

What is consent? Consent is defined by section 74 Sexual Offences Act 2003. Someone consents to vaginal, anal or oral penetration only if s/he agrees by choice to that penetration and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice. Consent to sexual activity may be given to one sort of sexual activity but not another, e.g.to vaginal but not anal sex or penetration with conditions, such as wearing a condom. Consent can be withdrawn at any time during sexual activity and each time activity occurs. In investigating the suspect, it must be established what steps, if any, the suspect took to obtain the complainant’s consent and the prosecution must prove that the suspect did not have a reasonable belief that the complainant was consenting. There is a big difference between consensual sex and rape. This aide focuses on consent, as allegations of rape often involve the word of the complainant against that of the suspect. The aim is to challenge assumptions about consent and the associated victim-blaming myths/stereotypes and highlight the suspect’s behaviour and motives to prove he/she did not reasonably believe the victim was consenting. We provide guidance to the police, prosecutors and advocates to identify and explain the differences, highlighting where evidence can be gathered and how the case can be presented in court. Targeting Victims of rape are often selected and targeted by offenders because of ease of access and opportunity - current partner, family, friend, someone who is vulnerable through mental health/ learning/physical disabilities, someone who sells sex, someone who is isolated or in an institution, has poor communication skills, is young, in a current or past relationship with the offender, or is compromised through drink/drugs. -

First Nations Conceptual Frameworks and Applied Models on Ethics, Privacy, and Consent in Health Research and Information

FIRST NATIONS CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORKS AND APPLIED MODELS ON ETHICS, PRIVACY, AND CONSENT IN HEALTH RESEARCH AND INFORMATION SUMMARY REPORT FIRST NATIONS CENTRE NOVEMBER 2006 FIRST NATIONS CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORKS AND APPLIED MODELS ON ETHICS, PRIVACY, AND CONSENT IN HEALTH RESEARCH AND INFORMATION SUMMARY REPORT Introduction This report contains findings from a collaborative project between Research Director Youngblood Henderson of the Native Law Centre of Canada and the First Nations Centre (FNC) at the National Aboriginal Health Organization (NAHO), presented to the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). The project supports the fulfillment of CIHR Objective #4, Developing New Conceptual Paradigms for Addressing Privacy Challenges of the strategic initiative, Compelling Values: Privacy, Access to Data and Health Research. The objectives of the project were to identify and articulate First Nations (FN) conceptual frameworks and models on ethics, privacy and consent related to health research and information, based on FN perspectives, values and norms. The research study was iterative and conducted in three phases: Phase 1 involved a comprehensive literature review and analysis, and the development of a list of key FN participants; Phase 2 involved data collection with discussions, focus groups, and vowed Dialogue Circles with selected FN participants; and Phase 3 involved the analysis and synthesis of research findings of the literature review, focus groups and dialogues, and the preparation of a final report. The center pole of the research lodge was the vowed Dialogue Circles (8 to 10 participants each). The structural framework of the vowed Dialogue Circles conformed to Blackfoot ceremonialist and Elder Crowshoe and Manneschmidt’s book, Akak'stiman. -

Informed Consent and Social Media

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Birkbeck Institutional Research Online Informed, uninformed and participative consent in social media research Dr. Daniel Nunan Henley Business School, University of Reading Dr. Baskin Yenicioglu Henley Business School, University of Reading Accepted for publication in the International Journal of Market Research Abstract The use of online data is becoming increasingly essential for the generation of insight in today’s research environment. This reflects the much wide range of data available online and the key role that social media now plays in interpersonal communication. However, the process of gaining permission to use social media data for research purposes creates a number of significant issues when considering compatibility with professional ethics guidelines. This paper critically explores the application of existing informed consent policies to social media research and compares with the form of consent gained by the social networks themselves, which we label 'uninformed consent'. We argue that, as currently constructed, informed consent carries assumptions about the nature of privacy that are not consistent with the way that consumers behave in an the online environment. On the other hand uninformed consent relies on asymmetric relationships that are unlikely to succeed in an environment based on co- creation of value. The paper highlights the ethical ambiguity created by current approaches for gaining customer consent, and proposes a new conceptual framework based on participative consent that allows for greater alignment between consumer privacy and ethical concerns. Introduction Driven by the rise of online social networks, mobile computing and other data-centric technologies, online data gathering has become a significant feature of contemporary market research. -

Political Obligation and Lockean Contract Theory

Acta Cogitata: An Undergraduate Journal in Philosophy Volume 7 Article 6 Political Obligation and Lockean Contract Theory Samantha Fritz Youngstown State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.emich.edu/ac Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Fritz, Samantha () "Political Obligation and Lockean Contract Theory," Acta Cogitata: An Undergraduate Journal in Philosophy: Vol. 7 , Article 6. Available at: https://commons.emich.edu/ac/vol7/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History and Philosophy at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Acta Cogitata: An Undergraduate Journal in Philosophy by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. Samantha Fritz Political Obligation and Lockean Contract Theory POLITICAL OBLIGATION AND LOCKEAN CONTRACT THEORY Samantha Fritz Youngstown State University Abstract In John Locke’s Second Treatise of Government, he presents his notion of social contract theory: individuals come together, leave the state of perfect freedom, and consent to give up certain rights to the State so the State can protect its members. He grounds duties and obligations to the government on the basis of consent. Because one consents to the State, either tacitly or expressly, one has consented to taking on political obligations owed to the State. Locke also notes that individuals can withdraw consent and leave the State. This paper challenges the view that political obligation can exist under Locke’s social contract theory. This paper first provides background for the argument by explaining Locke’s position.