Political Obligation and Lockean Contract Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jus Cogens As a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr

Penn State International Law Review Volume 29 Article 2 Number 2 Penn State International Law Review 9-1-2010 Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Petsche, Dr. Markus (2010) "Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 29: No. 2, Article 2. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol29/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Articles I Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche* Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .............................................. 235 I. THE INAPPROPRIATENESS OF CHARACTERIZING JUS COGENS AS A RULE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE LIMITED RELEVANCE OF JUS COGENS FOR THE PRACTICE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW...................................238 A. FundamentalConceptual and Theoretical Flaws ofJus Cogens .................................... 238 1. Origins of Jus Cogens. .................. ..... 238 2. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking Substance........ 242 3. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Procedure for Its Determination. ............ ......... .......... 243 4. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Proper Theoretical Basis.......................... 245 B. The Limited Relevance of Jus Cogens for the Law of Treaties: Rare and Unsuccessful Reliance on Jus * DEA (Paris 1); LL.M. (NYU); Ph.D. -

Indigenous and Tribal People's Rights Over Their Ancestral Lands

INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 56/09 30 December 2009 Original: Spanish INDIGENOUS AND TRIBAL PEOPLES’ RIGHTS OVER THEIR ANCESTRAL LANDS AND NATURAL RESOURCES Norms and Jurisprudence of the Inter‐American Human Rights System 2010 Internet: http://www.cidh.org E‐mail: [email protected] OAS Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data Derechos de los pueblos indígenas y tribales sobre sus tierras ancestrales y recursos naturales: Normas y jurisprudencia del sistema interamericano de derechos humanos = Indigenous and tribal people’s rights over their ancestral lands and natural resources: Norms and jurisprudence of the Inter‐American human rights system / [Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights.] p. ; cm. (OEA documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L)(OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978‐0‐8270‐5580‐3 1. Human rights‐‐America. 2. Indigenous peoples‐‐Civil rights‐‐America. 3. Indigenous peoples‐‐Land tenure‐‐America. 4. Indigenous peoples‐‐Legal status, laws, etc.‐‐America. 5. Natural resources‐‐Law and legislation‐‐America. I. Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. II Series. III. Series. OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.56/09 Document published thanks to the financial support of Denmark and Spain Positions herein expressed are those of the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights and do not reflect the views of Denmark or Spain Approved by the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights on December 30, 2009 INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS MEMBERS Luz Patricia Mejía Guerrero Víctor E. Abramovich Felipe González Sir Clare Kamau Roberts Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro Florentín Meléndez Paolo G. Carozza ****** Executive Secretary: Santiago A. -

Do Diffusion Protocols Govern Cascade Growth?

Proceedings of the Twelfth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM 2018) Do Diffusion Protocols Govern Cascade Growth? Justin Cheng,1 Jon Kleinberg,2 Jure Leskovec,3 David Liben-Nowell,4 Bogdan State,1 Karthik Subbian,1 Lada Adamic1 [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 1Facebook, 2Cornell University, 3Stanford University, 4Carleton College Abstract Large cascades can develop in online social networks as peo- ple share information with one another. Though simple re- share cascades have been studied extensively, the full range of cascading behaviors on social media is much more di- verse. Here we study how diffusion protocols, or the social ex- changes that enable information transmission, affect cascade growth, analogous to the way communication protocols de- fine how information is transmitted from one point to another. Studying 98 of the largest information cascades on Facebook, we find a wide range of diffusion protocols – from cascading reshares of images, which use a simple protocol of tapping a single button for propagation, to the ALS Ice Bucket Chal- lenge, whose diffusion protocol involved individuals creating and posting a video, and then nominating specific others to do the same. We find recurring classes of diffusion protocols, and identify two key counterbalancing factors in the con- struction of these protocols, with implications for a cascade’s growth: the effort required to participate in the cascade, and Figure 1: The diffusion tree of a cascade with a volunteer the social cost of staying on the sidelines. -

Reflections on Social Norms and Human Rights

The Psychology of Social Norms and the Promotion of Human Rights Deborah A. Prentice Princeton University Chapter to appear in R. Goodman, D. Jinks, & A. K. Woods (Eds.), Understanding social action, promoting human rights. New York: Oxford University Press. This chapter was written while I was Visiting Faculty in the School of Social Sciences at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, NJ. I would like to thank Jeremy Adelman, JoAnne Gowa, Bob Keohane, Eric Maskin, Dale Miller, Catherine Ross, Teemu Ruskola, Rick Shweder, and Eric Weitz for helpful discussions and comments on earlier drafts of the chapter. Please direct correspondence to: Deborah Prentice Department of Psychology Princeton University Green Hall Princeton, NJ 08540 [email protected] 1 Promoting human rights means changing behavior: Changing the behavior of governments that mistreat suspected criminals, opponents of their policies, supporters of their political rivals, and members of particular gender, ethnic, or religious groups; changing the behavior of corporations that mistreat their workers, damage the environment, and produce unsafe products; and changing the behavior of citizens who mistreat their spouses, children, and neighbors. In this chapter, I consider what an understanding of how social norms function psychologically has to contribute to this very worthy project. Social norms have proven to be an effective mechanism for changing health-related and environmental behaviors, so there is good reason to think that they might be helpful in the human-rights domain as well. In the social sciences, social norms are defined as socially shared and enforced attitudes specifying what to do and what not to do in a given situation (see Elster, 1990; Sunstein, 1997). -

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don't Have Sex Without Them

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don’t Have Sex Without Them A Lesson Plan from Rights, Respect, Responsibility: A K-12 Curriculum Fostering responsibility by respecting young people’s rights to honest sexuality education. ADVANCE PREPARATION FOR LESSON: NSES ALIGNMENT: • Download the YouTube video on consent, “2 Minutes Will By the end of 12th grade, Change the Way You Think About Consent,” at https://www. students will be able to: youtube.com/watch?v=laMtr-rUEmY. HR.12.CC.3 – Define sexual consent and explain its • Also download the trailer for Pitch Perfect 2 - The Ellen Show implications for sexual decision- version (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBwOYQd21TY), making. queuing it up to play a brief clip between 2:10 and 2:27. PS.12.CC.3 – Explain why using tricks, threats or coercion in • If you cannot download and save these to your desktop in relationships is wrong. advance, talk with your school’s IT person to ensure you have HR.12.INF.2 – Analyze factors, internet access to that link during class. including alcohol and other substances, that can affect the • Print out the skit scenarios and cut out each pair, making sure ability to give or perceive the the correct person 1 goes with the correct person 2. Determine provision of consent to sexual how many pairs there will be in your class and make several activity. copies of each scenario, enough for each pair to get one. TARGET GRADE: Grade 10 LEARNING OBJECTIVES: Lesson 1 By the end of this lesson, students will be able to: 1. -

A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, North America English Language and Literature 6-11-2009 A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau Jack Turner University of Washington Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Turner, Jack, "A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau" (2009). Literature in English, North America. 70. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_north_america/70 A Political Companion to Henr y David Thoreau POLITIcaL COMpaNIONS TO GREat AMERIcaN AUthORS Series Editor: Patrick J. Deneen, Georgetown University The Political Companions to Great American Authors series illuminates the complex political thought of the nation’s most celebrated writers from the founding era to the present. The goals of the series are to demonstrate how American political thought is understood and represented by great Ameri- can writers and to describe how our polity’s understanding of fundamental principles such as democracy, equality, freedom, toleration, and fraternity has been influenced by these canonical authors. The series features a broad spectrum of political theorists, philoso- phers, and literary critics and scholars whose work examines classic authors and seeks to explain their continuing influence on American political, social, intellectual, and cultural life. This series reappraises esteemed American authors and evaluates their writings as lasting works of art that continue to inform and guide the American democratic experiment. -

Cascading Leadership

FACULTY OF PSYCHOLOGY AND EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES Cascading Leadership Emile Jeuken Doctoral thesis offered to obtain the degree of Doctor of Psychology (PhD) Supervisor: Prof. dr. Martin Euwema Co-supervisor: Prof. dr. Wilmar Schaufeli 2016 Funding Dissertation funded by “de Belastingdienst” (the Netherlands Tax and Customs Administration). I Summary Cascading leadership is defined as the co-occurrence of leaders’ values, attitudes and behaviors, at different hierarchal levels within an organization. The aim of this doctoral thesis is to get a better understanding of cascading leadership as well as the mechanisms underlying the phenomenon, with special focus on perceived power. We conducted three studies, using three different research methods: a systematic literature review, a field survey study, and an experimental study. Chapter 1 introduces cascading leadership research, exploring both societal and academic relevance, as well as the aims of our study and overview of the PhD. Chapter 2 presents our first study. As there has not been published a systematic review on the subject before, we conducted such a literature review, resulting in a selection of 18 papers, with 19 empirical studies. These studies cover a wide array of cascading constructs and theoretical perspectives. However, all studies are cross sectional, typically survey studies. Positional power and sense of power appear to play an important role, however have hardly been studied. Chapter 3 describes our second study, in which we investigate whether trust in leadership cascades across three hierarchical levels of leadership and whether it is directly and indirectly related to work engagement of the front-line employee. Only one other cascading leadership study to date included four hierarchical levels. -

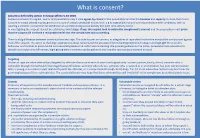

What Is Consent?

What is consent? Consent is defined by section 74 Sexual Offences Act 2003. Someone consents to vaginal, anal or oral penetration only if s/he agrees by choice to that penetration and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice. Consent to sexual activity may be given to one sort of sexual activity but not another, e.g.to vaginal but not anal sex or penetration with conditions, such as wearing a condom. Consent can be withdrawn at any time during sexual activity and each time activity occurs. In investigating the suspect, it must be established what steps, if any, the suspect took to obtain the complainant’s consent and the prosecution must prove that the suspect did not have a reasonable belief that the complainant was consenting. There is a big difference between consensual sex and rape. This aide focuses on consent, as allegations of rape often involve the word of the complainant against that of the suspect. The aim is to challenge assumptions about consent and the associated victim-blaming myths/stereotypes and highlight the suspect’s behaviour and motives to prove he did not reasonably believe the victim was consenting. We provide guidance to the police, prosecutors and advocates to identify and explain the differences, highlighting where evidence can be gathered and how the case can be presented in court. Targeting Victims of rape are often selected and targeted by offenders because of ease of access and opportunity - current partner, family, friend, someone who is vulnerable through mental health/ learning/physical difficulties, someone who sells sex, someone who is isolated or in an institution, has poor communication skills, is young, in a current or past relationship with the offender, or is compromised through drink/drugs. -

Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies

future internet Review Trust, but Verify: Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies Brian Pickering IT Innovation, Electronics and Computing, University of Southampton, University Road, Southampton SO17 1BJ, UK; [email protected] Abstract: To use technology or engage with research or medical treatment typically requires user consent: agreeing to terms of use with technology or services, or providing informed consent for research participation, for clinical trials and medical intervention, or as one legal basis for processing personal data. Introducing AI technologies, where explainability and trustworthiness are focus items for both government guidelines and responsible technologists, imposes additional challenges. Understanding enough of the technology to be able to make an informed decision, or consent, is essential but involves an acceptance of uncertain outcomes. Further, the contribution of AI- enabled technologies not least during the COVID-19 pandemic raises ethical concerns about the governance associated with their development and deployment. Using three typical scenarios— contact tracing, big data analytics and research during public emergencies—this paper explores a trust- based alternative to consent. Unlike existing consent-based mechanisms, this approach sees consent as a typical behavioural response to perceived contextual characteristics. Decisions to engage derive from the assumption that all relevant stakeholders including research participants will negotiate on an ongoing basis. Accepting dynamic negotiation between the main stakeholders as proposed here introduces a specifically socio–psychological perspective into the debate about human responses Citation: Pickering, B. Trust, but to artificial intelligence. This trust-based consent process leads to a set of recommendations for the Verify: Informed Consent, AI ethical use of advanced technologies as well as for the ethical review of applied research projects. -

Social Contract As Bourgeois Ideology Stephen C

Social Contract as Bourgeois Ideology Stephen C. Ferguson II John Rawls (Photo © Steve Pyke.) Since the publication of John Rawls’ magnum opus A Theory of Justice in 1971, there has been a significant resurgence of philosophical work in the tradition of contractarianism. The distinguished bourgeois political philosopher Robert Nozick has argued that A Theory of Justice is one of the most important works in political philosophy since the writings of John Stuart Mill. “Political philosophers,” Nozick concludes, “now must either work within Rawls’ theory or explain why.”1 It is not far from the truth that Rawls single-handedly not only gave life to analytical political philosophy, but also resuscitated contractarianism, a philosophical tradition that — in many respects — had been lying dormant in a philosophical coma. In fact, social contract theory has become the hegemonic tradition in liberal social and political philosophy. As the Afro-Caribbean My thanks for advice, guidance and/or invaluable criticism of earlier drafts to John H. McClendon III, Ann Cudd, Rex Martin, Tom Tuozzo, Robert J. Antonio and Tariq Al-Jamil. I would also like to extend a hearty thanks to Greg Meyerson and David Siar for their invaluable editorial comments. And, lastly, thanks to my wife, Cassondra, and my two sons, Kendall and Trey, for your unqualified love and support in times of tranquility as well as times of crisis. 1 Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State and Utopia (New York: Basic Books, 1974): 183. Copyright © 2007 by Stephen C. Ferguson and Cultural Logic, ISSN 1097-3087 Ferguson 2 philosopher Charles Mills has put it, contract talk is, after all, the political lingua franca of our times.2 In this essay, we will examine the ideological character and theoretical content of contractrarianism as a philosophical tradition beginning with its classic exposition in the works of Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and, finally, culminating in the work of John Rawls. -

The Philosophy of Contractual Obligation, 21 Marq

Marquette Law Review Volume 21 Article 1 Issue 4 June 1937 The hiP losophy of Contractual Obligation Robert J. Buer Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Robert J. Buer, The Philosophy of Contractual Obligation, 21 Marq. L. Rev. 157 (1937). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol21/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARQUETTE LAW REVIEW VOLUME XXI JUNE, 1937 NUMBER FOUR THE PHILOSOPHY OF CONTRACTUAL OBLIGATION ROBERT J. BUER THE HISTORY OF CONSIDERATION T HE doctrine of consideration has stood for several centuries as a pillar in the law of contracts, an essential to their enforcement. Students of the law have, from the first instance of their contacts with the great body of jurisprudence, regarded consideration as one of the rudimentary principles upon which future knowledge of the refine- ments and technicalities of the law must be based. However, in recent years, chiefly because of the exceptions to and inconsistencies of the fundamental rule that every contract to be enforceable must be sup- ported by a sufficient consideration, liberal students of the law have advocated the alteration or abolishment of the rule.' These advocates of change in the doctrine are not without sound historical authority as a basis for their demands. -

'History, Method and Pluralism: a Re-Interpretation of Isaiah Berlin's

HISTORY, METHOD, AND PLURALISM A Re-interpretation of Isaiah Berlin’s Political Thought Thesis submitted to the University of London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by HAOYEH London School of Economics and Political Science 2005 UMI Number: U205195 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U205195 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 S 510 Abstract of the Thesis In the literature on Berlin to date, two broad approaches to study his political thought can be detected. The first is the piecemeal approach, which tends to single out an element of Berlin’s thought (for example, his distinction between negative liberty and positive liberty) for exposition or criticism, leaving other elements unaccounted. And the second is the holistic approach, which pays attention to the overall structure of Berlin’s thought as a whole, in particular the relation between his defence for negative liberty and pluralism. This thesis is to defend the holistic approach against the piecemeal approach, but its interpretation will differ from the two representative readings, offered by Claude J.