Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jus Cogens As a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr

Penn State International Law Review Volume 29 Article 2 Number 2 Penn State International Law Review 9-1-2010 Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Petsche, Dr. Markus (2010) "Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 29: No. 2, Article 2. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol29/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Articles I Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche* Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .............................................. 235 I. THE INAPPROPRIATENESS OF CHARACTERIZING JUS COGENS AS A RULE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE LIMITED RELEVANCE OF JUS COGENS FOR THE PRACTICE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW...................................238 A. FundamentalConceptual and Theoretical Flaws ofJus Cogens .................................... 238 1. Origins of Jus Cogens. .................. ..... 238 2. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking Substance........ 242 3. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Procedure for Its Determination. ............ ......... .......... 243 4. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Proper Theoretical Basis.......................... 245 B. The Limited Relevance of Jus Cogens for the Law of Treaties: Rare and Unsuccessful Reliance on Jus * DEA (Paris 1); LL.M. (NYU); Ph.D. -

Office for Research Procedure

OFFICE FOR RESEARCH PROCEDURE INFORMED CONSENT PROCEDURES & WRITING PARTICIPANT INFORMATION AND CONSENT FORMS FOR RESEARCH Purpose: To describe the procedures related to informed consent procedures and writing patient information consent forms (PICF). To ensure that Austin Health adheres to the legal and ethical responsibility of obtaining a valid and informed consent for research participants. Scope: All phases of clinical investigation of medicinal products, medical devices, diagnostics and therapeutic interventions and research studies. Staff this document applies to: Principal Investigators, Associate Investigators, Clinical Research Coordinators, other staff involved in research-related activities. State any related Austin Health policies, procedures or guidelines: Austin Health Clinical Policy – (Informed) Consent (To Diagnosis & Treatment) Policy Document No: 2179 Policy Overview: A valid and informed consent will be obtained and documented prior to Austin Health research commencing. Emergency research procedures will be undertaken in compliance with the Guardianship and Administration Act 1986. Summary: For consent to be valid, it must be: freely given; specific to the proposed research and/or intervention; given by a person who is legally able to consent. 1. Elements of Consent: A consent is valid if it is: a) Freely given. b) Specific to the proposed research and/or intervention; c) Given by a person who is legally able to consent. AH VMIA SOP No. 006 Disclaimer: This Document has been developed for Austin Health use and has been specifically designed for Austin Health circumstances. Printed versions can only be considered up-to-date for a period of one month from the printing date after which, the latest version should be downloaded from ePPIC. -

Indigenous and Tribal People's Rights Over Their Ancestral Lands

INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 56/09 30 December 2009 Original: Spanish INDIGENOUS AND TRIBAL PEOPLES’ RIGHTS OVER THEIR ANCESTRAL LANDS AND NATURAL RESOURCES Norms and Jurisprudence of the Inter‐American Human Rights System 2010 Internet: http://www.cidh.org E‐mail: [email protected] OAS Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data Derechos de los pueblos indígenas y tribales sobre sus tierras ancestrales y recursos naturales: Normas y jurisprudencia del sistema interamericano de derechos humanos = Indigenous and tribal people’s rights over their ancestral lands and natural resources: Norms and jurisprudence of the Inter‐American human rights system / [Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights.] p. ; cm. (OEA documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L)(OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978‐0‐8270‐5580‐3 1. Human rights‐‐America. 2. Indigenous peoples‐‐Civil rights‐‐America. 3. Indigenous peoples‐‐Land tenure‐‐America. 4. Indigenous peoples‐‐Legal status, laws, etc.‐‐America. 5. Natural resources‐‐Law and legislation‐‐America. I. Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. II Series. III. Series. OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.56/09 Document published thanks to the financial support of Denmark and Spain Positions herein expressed are those of the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights and do not reflect the views of Denmark or Spain Approved by the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights on December 30, 2009 INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS MEMBERS Luz Patricia Mejía Guerrero Víctor E. Abramovich Felipe González Sir Clare Kamau Roberts Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro Florentín Meléndez Paolo G. Carozza ****** Executive Secretary: Santiago A. -

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don't Have Sex Without Them

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don’t Have Sex Without Them A Lesson Plan from Rights, Respect, Responsibility: A K-12 Curriculum Fostering responsibility by respecting young people’s rights to honest sexuality education. ADVANCE PREPARATION FOR LESSON: NSES ALIGNMENT: • Download the YouTube video on consent, “2 Minutes Will By the end of 12th grade, Change the Way You Think About Consent,” at https://www. students will be able to: youtube.com/watch?v=laMtr-rUEmY. HR.12.CC.3 – Define sexual consent and explain its • Also download the trailer for Pitch Perfect 2 - The Ellen Show implications for sexual decision- version (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBwOYQd21TY), making. queuing it up to play a brief clip between 2:10 and 2:27. PS.12.CC.3 – Explain why using tricks, threats or coercion in • If you cannot download and save these to your desktop in relationships is wrong. advance, talk with your school’s IT person to ensure you have HR.12.INF.2 – Analyze factors, internet access to that link during class. including alcohol and other substances, that can affect the • Print out the skit scenarios and cut out each pair, making sure ability to give or perceive the the correct person 1 goes with the correct person 2. Determine provision of consent to sexual how many pairs there will be in your class and make several activity. copies of each scenario, enough for each pair to get one. TARGET GRADE: Grade 10 LEARNING OBJECTIVES: Lesson 1 By the end of this lesson, students will be able to: 1. -

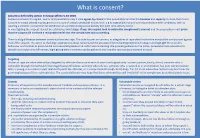

What Is Consent?

What is consent? Consent is defined by section 74 Sexual Offences Act 2003. Someone consents to vaginal, anal or oral penetration only if s/he agrees by choice to that penetration and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice. Consent to sexual activity may be given to one sort of sexual activity but not another, e.g.to vaginal but not anal sex or penetration with conditions, such as wearing a condom. Consent can be withdrawn at any time during sexual activity and each time activity occurs. In investigating the suspect, it must be established what steps, if any, the suspect took to obtain the complainant’s consent and the prosecution must prove that the suspect did not have a reasonable belief that the complainant was consenting. There is a big difference between consensual sex and rape. This aide focuses on consent, as allegations of rape often involve the word of the complainant against that of the suspect. The aim is to challenge assumptions about consent and the associated victim-blaming myths/stereotypes and highlight the suspect’s behaviour and motives to prove he did not reasonably believe the victim was consenting. We provide guidance to the police, prosecutors and advocates to identify and explain the differences, highlighting where evidence can be gathered and how the case can be presented in court. Targeting Victims of rape are often selected and targeted by offenders because of ease of access and opportunity - current partner, family, friend, someone who is vulnerable through mental health/ learning/physical difficulties, someone who sells sex, someone who is isolated or in an institution, has poor communication skills, is young, in a current or past relationship with the offender, or is compromised through drink/drugs. -

RESEARCH STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES Documentation of Research Study Procedures in the Patients' Health Record

DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS Research Service Policy Memorandum 11-42 South Texas Veterans Health Care System San Antonio, Texas 78229-4404 October 18, 2011 RESEARCH STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES Documentation of Research Study Procedures in the Patients' Health Record 1. PURPOSE: To describe the policies and procedures for the documentation of human research activities conducted at STVHCS in a patient's health record when a participant (research subject) is involved in a human research study. 2. POLICY: A research participant's health record includes the electronic medical record and any hard copy documentation located in Medical Records, combined, and is also known as the legal health record. Research files maintained by the Principle Investigators (PIs) and/or research staff are not part of the legal health record. A research record must be created or updated, and a progress note created, in the legal medical record when informed consent is obtained, a research visit has the potential to impact medical care (i.e. the research intervention may lead to physical or psychological adverse events), when the research requires use of any clinical resources (i.e. radiology, cardiology, pharmacy), or when a participant is disenrolled or terminated from a study. 3. ACTION: a. Documentation of the informed consent process (1) The PI or designated, trained study staff initiates the informed consent process with the use of the VA Form 10-1086 (lC document). (2) The IC document must be signed by (a) The participant or the participant's legally authorized representative (b) The person obtaining the informed consent (3) The PI or designated, trained study staff must enter a "Research ConsentiEnrollment Note" in the computerized patient record system (CPRS) after informed consent is obtained. -

METHODS for REMOTE CLINICAL TRIALS Authors: Jennifer Dahne, Phd and Matthew J

METHODS FOR REMOTE CLINICAL TRIALS https://www.hrsa.gov/library/telehealth-coe-musc Authors: Jennifer Dahne, PhD and Matthew J. Carpenter, PhD Background Nearly all clinical trials are conducted locally, with recruitment limited to those who live proximal to a clinical trial site. These local trials struggle to recruit large, diverse, representative study samples. Consequently, many fail to meet their target enrollment and/or have unrepresentative samples. Trials that target specific subgroups of participants (e.g., low socioeconomic status, rural) or that address rare clinical conditions face even greater challenges, to the point where local trials may not even be feasible. Multi-site clinical trials can overcome some of these hurdles but incur their own unique challenges, most notably the need for sizable and costly infrastructure. With recent advances in telehealth and mobile health technologies, there is now a promising alternative: Remote clinical trials. Remote clinical trials (sometimes referred to as “decentralized clinical trials”) are led and coordinated by a local investigative team, but are based remotely, within a community, state, or nation. Such trials rely on remote methods to recruit participants into trials, consent study participants, deliver interventions, and maintain all follow-up assessments from a distance. Because participants are not required to attend in-person visits, remote trials improve sample representativeness, expand trial access, and enhance study feasibility[1, 2]. Remote clinical trials are now timelier in light of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) global health pandemic, which has resulted in rapid requirements to shift ongoing clinical trials to remote delivery and assessment platforms. Indeed, guidance from numerous global health agencies now highlights that clinical trials procedures should shift, where possible, to alternative remote methods of delivery[3-5]. -

Dear Potential Research Participant, Thank You for Your Interest in This

Child Study Lab / Courtney A. Lewis UF-HSC PO Box 100165 Gainesville, FL 32610-016 Voice: (352) 273-5238 Dear Potential Research Participant, Thank you for your interest in this research study. This project is studying a brief format of Parent Child Interaction Therapy or PCIT. PCIT has been used for over 20 years and is a well established treatment for parents with young children who display problem behaviors such as aggression, disobedience, and hyperactivity. Traditionally parents work with their PCIT therapist for an average of 15 weeks. This study is examining a shorter version of PCIT. Parents who participate will be involved in the project for approximately 3 months. Below are brief descriptions of the screening, treatment, and follow-up phases included in this project. Screening Phase: The screening phase is a one week period where we collect information from you to see if our program would be a good fit for your family. During this phase you will answer questions about your child’s behavior, observe your child’s behavior at home, and come to the Child Study Lab located at UF/Shands for a 1.5 hour assessment. During this appointment you will review and complete a full informed consent. Treatment Phase: The treatment phase is divided into two parts. During the first part you and your child will attend five, two- hour therapy sessions. These will occur during a week-long period. During these sessions you will learn and practice skills to help playtime with your child be more calm and fun. We also will teach you effective discipline strategies. -

Doctor-Patient Communication: the Experiences of Black Caribbean Women Patients with Diabetes

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks Theses and Dissertations Abraham S. Fischler College of Education 2020 Doctor-Patient Communication: The Experiences of Black Caribbean Women Patients With Diabetes Rosanne Paul-Bruno Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/fse_etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Education Commons, and the Public Health Education and Promotion Commons Share Feedback About This Item This Dissertation is brought to you by the Abraham S. Fischler College of Education at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Doctor-Patient Communication: The Experiences of Black Caribbean Women Patients With Diabetes by Rosanne Paul-Bruno An Applied Dissertation Submitted to the Abraham S. Fischler College of Education and School of Criminal Justice in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education Nova Southeastern University 2020 Approval Page This applied dissertation was submitted by Rosanne Paul-Bruno under the direction of the persons listed below. It was submitted to the Abraham S. Fischler College of Education and School of Criminal Justice and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education at Nova Southeastern University. Candace H. Lacey, PhD Committee Chair Charlene Desir, EdD Committee Member Kimberly Durham, PsyD Dean ii Statement of Original Work I declare the following: I have read the Code of Student Conduct and Academic Responsibility as described in the Student Handbook of Nova Southeastern University. This applied dissertation represents my original work, except where I have acknowledged the ideas, words, or material of other authors. -

The Barriers Encountered in Telemedicine Implementation by Health Care Practitioners

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2015 The aB rriers Encountered in Telemedicine Implementation by Health Care Practitioners Olantunji Obikunle Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Business Commons, and the Health and Medical Administration Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Management and Technology This is to certify that the doctoral study by Olatunji Obikunle has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Kenneth Gossett, Committee Chairperson, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Dr. Roger Mayer, Committee Member, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Dr. Charles Needham, University Reviewer, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2015 Abstract The Barriers Encountered in Telemedicine Implementation by Health Care Practitioners by Olatunji Obikunle Project Management Professional (PMP), 2001 MSc Business Systems Analysis and Design, City University, London, -

Sample Informed Consent Language Library Describing Technologies Used in Research

Sample Informed Consent Language Library Describing technologies used in research Emerging Technologies, Ethics, and Research Data Committee Harvard Catalyst Regulatory Foundations, Ethics, and Law Program Table of Contents Overview ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Chat Technology ......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Data Collection and Privacy Considerations .......................................................................................................................... 6 Transmission of Research Data ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Online Tracking and Cookies .................................................................................................................................................. 10 Storage and Archiving including Cloud, Back-ups, and Access ...................................................................................... 12 Research Data Destruction ............................................................................................................................................................ 14 Electronic Informed Consent ................................................................................................................................................. -

Whatsapp in Health Communication: the Case of Eye Health in Deprived Settings in India

WhatsApp In Health Communication: The Case Of Eye Health In Deprived Settings In India CHANDRANI MAITRA PhD 2021 WhatsApp In Health Communication: The Case Of Eye Health In Deprived Settings In India CHANDRANI MAITRA A Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfilment Of The Requirements Of Manchester Metropolitan University For The Degree Of Philosophy Department Of Languages, Information And Communications Manchester Metropolitan University March 2021 Supervisory Team Prof Jennifer Rowley Dr Esperanza Miyake iii Abstract The aim of this study was to explore the use of WhatsApp in developing a community based practice of eye health promotion in a deprived locality bordering a metropolitan city in India. Globally, 285 million people are visually impaired, a quarter of whom live in India, which results in lower employment and lessened productivity. The national blindness prevention strategy aims at eyecare promotion through health behaviour change achieved by raising awareness. Traditionally, health behaviour change has been achieved through conventional communication platforms like radio and television-. The recent exponential development in social media technology, ubiquitous and inexpensive, offers significant potential for two-way communication in real time with a wider audience, including those from disadvantaged groups. WhatsApp, an inexpensive social media platform which is widely used in the Indian subcontinent, may offer an important channel for eyecare related health communication. Importantly, no study has systematically evaluated WhatsApp in promoting health communication on eye care in India, specifically in its largely deprived population. This qualitative study used WhatsApp (as an interventional tool) to create an information resource link on basic eye care between a tertiary city based healthcare provider and the deprived community, resident in the fringe of the city.