Personal Autonomy and Informed Consent: Conceptual and Normative Analyses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jus Cogens As a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr

Penn State International Law Review Volume 29 Article 2 Number 2 Penn State International Law Review 9-1-2010 Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Petsche, Dr. Markus (2010) "Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 29: No. 2, Article 2. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol29/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Articles I Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche* Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .............................................. 235 I. THE INAPPROPRIATENESS OF CHARACTERIZING JUS COGENS AS A RULE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE LIMITED RELEVANCE OF JUS COGENS FOR THE PRACTICE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW...................................238 A. FundamentalConceptual and Theoretical Flaws ofJus Cogens .................................... 238 1. Origins of Jus Cogens. .................. ..... 238 2. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking Substance........ 242 3. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Procedure for Its Determination. ............ ......... .......... 243 4. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Proper Theoretical Basis.......................... 245 B. The Limited Relevance of Jus Cogens for the Law of Treaties: Rare and Unsuccessful Reliance on Jus * DEA (Paris 1); LL.M. (NYU); Ph.D. -

Indigenous and Tribal People's Rights Over Their Ancestral Lands

INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 56/09 30 December 2009 Original: Spanish INDIGENOUS AND TRIBAL PEOPLES’ RIGHTS OVER THEIR ANCESTRAL LANDS AND NATURAL RESOURCES Norms and Jurisprudence of the Inter‐American Human Rights System 2010 Internet: http://www.cidh.org E‐mail: [email protected] OAS Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data Derechos de los pueblos indígenas y tribales sobre sus tierras ancestrales y recursos naturales: Normas y jurisprudencia del sistema interamericano de derechos humanos = Indigenous and tribal people’s rights over their ancestral lands and natural resources: Norms and jurisprudence of the Inter‐American human rights system / [Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights.] p. ; cm. (OEA documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L)(OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978‐0‐8270‐5580‐3 1. Human rights‐‐America. 2. Indigenous peoples‐‐Civil rights‐‐America. 3. Indigenous peoples‐‐Land tenure‐‐America. 4. Indigenous peoples‐‐Legal status, laws, etc.‐‐America. 5. Natural resources‐‐Law and legislation‐‐America. I. Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. II Series. III. Series. OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.56/09 Document published thanks to the financial support of Denmark and Spain Positions herein expressed are those of the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights and do not reflect the views of Denmark or Spain Approved by the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights on December 30, 2009 INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS MEMBERS Luz Patricia Mejía Guerrero Víctor E. Abramovich Felipe González Sir Clare Kamau Roberts Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro Florentín Meléndez Paolo G. Carozza ****** Executive Secretary: Santiago A. -

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don't Have Sex Without Them

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don’t Have Sex Without Them A Lesson Plan from Rights, Respect, Responsibility: A K-12 Curriculum Fostering responsibility by respecting young people’s rights to honest sexuality education. ADVANCE PREPARATION FOR LESSON: NSES ALIGNMENT: • Download the YouTube video on consent, “2 Minutes Will By the end of 12th grade, Change the Way You Think About Consent,” at https://www. students will be able to: youtube.com/watch?v=laMtr-rUEmY. HR.12.CC.3 – Define sexual consent and explain its • Also download the trailer for Pitch Perfect 2 - The Ellen Show implications for sexual decision- version (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBwOYQd21TY), making. queuing it up to play a brief clip between 2:10 and 2:27. PS.12.CC.3 – Explain why using tricks, threats or coercion in • If you cannot download and save these to your desktop in relationships is wrong. advance, talk with your school’s IT person to ensure you have HR.12.INF.2 – Analyze factors, internet access to that link during class. including alcohol and other substances, that can affect the • Print out the skit scenarios and cut out each pair, making sure ability to give or perceive the the correct person 1 goes with the correct person 2. Determine provision of consent to sexual how many pairs there will be in your class and make several activity. copies of each scenario, enough for each pair to get one. TARGET GRADE: Grade 10 LEARNING OBJECTIVES: Lesson 1 By the end of this lesson, students will be able to: 1. -

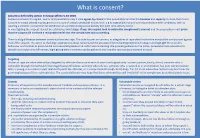

What Is Consent?

What is consent? Consent is defined by section 74 Sexual Offences Act 2003. Someone consents to vaginal, anal or oral penetration only if s/he agrees by choice to that penetration and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice. Consent to sexual activity may be given to one sort of sexual activity but not another, e.g.to vaginal but not anal sex or penetration with conditions, such as wearing a condom. Consent can be withdrawn at any time during sexual activity and each time activity occurs. In investigating the suspect, it must be established what steps, if any, the suspect took to obtain the complainant’s consent and the prosecution must prove that the suspect did not have a reasonable belief that the complainant was consenting. There is a big difference between consensual sex and rape. This aide focuses on consent, as allegations of rape often involve the word of the complainant against that of the suspect. The aim is to challenge assumptions about consent and the associated victim-blaming myths/stereotypes and highlight the suspect’s behaviour and motives to prove he did not reasonably believe the victim was consenting. We provide guidance to the police, prosecutors and advocates to identify and explain the differences, highlighting where evidence can be gathered and how the case can be presented in court. Targeting Victims of rape are often selected and targeted by offenders because of ease of access and opportunity - current partner, family, friend, someone who is vulnerable through mental health/ learning/physical difficulties, someone who sells sex, someone who is isolated or in an institution, has poor communication skills, is young, in a current or past relationship with the offender, or is compromised through drink/drugs. -

Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies

future internet Review Trust, but Verify: Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies Brian Pickering IT Innovation, Electronics and Computing, University of Southampton, University Road, Southampton SO17 1BJ, UK; [email protected] Abstract: To use technology or engage with research or medical treatment typically requires user consent: agreeing to terms of use with technology or services, or providing informed consent for research participation, for clinical trials and medical intervention, or as one legal basis for processing personal data. Introducing AI technologies, where explainability and trustworthiness are focus items for both government guidelines and responsible technologists, imposes additional challenges. Understanding enough of the technology to be able to make an informed decision, or consent, is essential but involves an acceptance of uncertain outcomes. Further, the contribution of AI- enabled technologies not least during the COVID-19 pandemic raises ethical concerns about the governance associated with their development and deployment. Using three typical scenarios— contact tracing, big data analytics and research during public emergencies—this paper explores a trust- based alternative to consent. Unlike existing consent-based mechanisms, this approach sees consent as a typical behavioural response to perceived contextual characteristics. Decisions to engage derive from the assumption that all relevant stakeholders including research participants will negotiate on an ongoing basis. Accepting dynamic negotiation between the main stakeholders as proposed here introduces a specifically socio–psychological perspective into the debate about human responses Citation: Pickering, B. Trust, but to artificial intelligence. This trust-based consent process leads to a set of recommendations for the Verify: Informed Consent, AI ethical use of advanced technologies as well as for the ethical review of applied research projects. -

Espinalt's Concept of Human WILL and Character and Its

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert 6 espinaLt’s coNcePt oF humaN Will aNd chaRacteR aNd Its coNsequeNces FoR 1 moRaL educatIoN Carme Giménez-Camins & Josep Gallifa abstract: This article deals with the human will and the individual character and their relevance in the moral sphere. After introducing the conative domain, it argues for the need to have a psychological and educational model of human character. The paper presents Espinalt’s (1920-1993) concepts of will and character and their consequences for education. After having explored human will and understanding the causes for the relative lack of consideration of will by modern psychology, a definition of character is presented as a result of exercising human will. Three different dimensions of character are considered: One more connected with instincts, another with culture, and the most distinctive of individual self-engraving. The third dimension leads to different considerations of education that are briefly explained. The Espinaltian vision is contrasted with other contemporary visions of human will and character. The social and historical forces with an influence on the education of the character are also considered. Finally the paper argues for the centrality of these approaches for a moral education which is based on Aristotelian views. Keywords: Espinalt, Human Will, Moral education, Aristotle, character 1 This paper was received on January 31, 2011 and was approved on March 27, 2011 122 RamoN LLuLL JouRNaL oF aPPLIed ethIcs 2011. Issue 2 INtRoductIoN the neoclassical model of the human psyche Traditionally the human psyche has been divided into three components: Cognition, affect and conation (Hilgard, 1980; Tallon, 1997). -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College of The

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts EXISTENTIALIST ROOTS OF FEMINIST ETHICS A Dissertation in Philosophy by Deniz Durmus Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2015 The dissertation of Deniz Durmus was reviewed and approved* by the following: Shannon Sullivan Professor of Philosophy Women's Studies, and African American Studies, Department Head, Dissertation Advisor, Co-Chair Committee Sarah Clark Miller Associate Professor of Philosophy, Associate Director of Rock Ethics Institute, Co-Chair Committee John Christman Professor of Philosophy, Women’s Studies Robert Bernasconi Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Philosophy, African American Studies Christine Clark Evans Professor of French and Francophone Studies, Women’s Studies Amy Allen Liberal Arts Professor of Philosophy, Head of Philosophy Department *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii ABSTRACT My dissertation “Existentialist Roots of Feminist Ethics” is an account of existentialist feminist ethics written from the perspective of ambiguous nature of interconnectedness of human freedoms. It explores existentialist tenets in feminist ethics and care ethics and reclaims existentialism as a resourceful theory in addressing global ethical issues. My dissertation moves beyond the once prevalent paradigm that feminist ethics should be devoid of any traditional ethical theories and it shows that an existential phenomenological ethics can complement feminist ethics in a productive way. The first chapter, introduces and discusses an existentialist notion of freedom based on Simone de Beauvoir and Jean Paul Sartre’s writings. In order to establish that human beings are metaphysically free, I explain notions of in-itself, for-itself, transcendence, immanence, facticity, and bad faith which are the basic notions of an existentialist notion of freedom. -

Human Challenge Trials for Vaccine Development: Regulatory Considerations

POST ECBS Version ENGLISH ONLY EXPERT COMMITTEE ON BIOLOGICAL STANDARDIZATION Geneva, 17 to 21 October 2016 Human Challenge Trials for Vaccine Development: regulatory considerations © World Health Organization 2016 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; email: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. -

Informed Consent and Refusal

CHAPTER 3 Informed Consent and Refusal Evolution of the doctrine of informed consent Elements of informed consent and refusal The nature of informed consent Exceptions to the consent requirement Mrs. Stack is a 67- year- old woman admitted with rectal bleeding, chronic renal in- sufficiency, diabetes, and blindness. On admission, she was alert and capacitated. Two weeks later, she suffered a cardiopulmonary arrest, was resuscitated and intu- bated, and was transferred to the medical intensive care unit (MICU) in an unrespon- sive and unstable state. Consent for emergency dialysis was obtained from her son, who is also her health care agent. Dialysis was repeated two days later. During the past several years, Mrs. Stack has consistently stated to her family and her primary care doctor that she would never want to be on chronic dialysis and she has refused it numerous times when it was recommended. The physician, who has known and treated Mrs. Stack for many years, also treated her daughter who had been on chronic dialysis for some time and had died after suffering a heart attack. According to the physician and the patient’s family, Mrs. Stack’s refusal of dialysis has been based on her conviction that her daughter died as a result of the dialysis treatments. Mrs. Stack’s mental status has cleared considerably and, despite the ventilator, she is able to communicate nonverbally. Although she appears to understand the benefits of dialysis and the consequences of refusing it, including deterioration and eventual death, she has consistently and vehemently refused further treatments. Her capacity to make this decision is not now in question. -

Rethinking Feminist Ethics

RETHINKING FEMINIST ETHICS The question of whether there can be distinctively female ethics is one of the most important and controversial debates in current gender studies, philosophy and psychology. Rethinking Feminist Ethics: Care, Trust and Empathy marks a bold intervention in these debates by bridging the ground between women theorists disenchanted with aspects of traditional ‘male’ ethics and traditional theorists who insist upon the need for some ethical principles. Daryl Koehn provides one of the first critical overviews of a wide range of alternative female/ feminist/feminine ethics defended by influential theorists such as Carol Gilligan, Annette Baier, Nel Noddings and Diana Meyers. She shows why these ethics in their current form are not defensible and proposes a radically new alternative. In the first section, Koehn identifies the major tenets of ethics of care, trust and empathy. She provides a lucid, searching analysis of why female ethics emphasize a relational, rather than individualistic, self and why they favor a more empathic, less rule-based, approach to human interactions. At the heart of the debate over alternative ethics is the question of whether female ethics of care, trust and empathy constitute a realistic, practical alternative to the rule- based ethics of Immanuel Kant, John Stuart Mill and John Rawls. Koehn concludes that they do not. Female ethics are plagued by many of the same problems they impute to ‘male’ ethics, including a failure to respect other individuals. In particular, female ethics favor the perspective of the caregiver, trustor and empathizer over the viewpoint of those who are on the receiving end of care, trust and empathy. -

Aristotle, Kant, JS Mill and Rawls Raphael Cohen-Almagor

1 On the Philosophical Foundations of Medical Ethics: Aristotle, Kant, JS Mill and Rawls Raphael Cohen-Almagor Ethics, Medicine and Public Health (Available online 22 November 2017). Abstract This article aims to trace back some of the theoretical foundations of medical ethics that stem from the philosophies of Aristotle, Immanuel Kant, John Stuart Mill and John Rawls. The four philosophers had in mind rational and autonomous human beings who are able to decide their destiny, who pave for themselves the path for their own happiness. It is argued that their philosophies have influenced the field of medical ethics as they crafted some very important principles of the field. I discuss the concept of autonomy according to Kant and JS Mill, Kant’s concepts of dignity, benevolence and beneficence, Mill’s Harm Principle (nonmaleficence), the concept of justice according to Aristotle, Mill and Rawls, and Aristotle’s concept of responsibility. Key words: Aristotle, Immanuel Kant, John Stuart Mill, autonomy, beneficence, benevolence, dignity, justice, nonmaleficence, responsibility, John Rawls Introduction What are the philosophical foundations of medical ethics? The term ethics is derived from Greek. ἦθος: Noun meaning 'character' or 'disposition'. It is used in Aristotle to denote those aspects of one's character that, through appropriate moral training, develop into virtues. ἦθος is related to the adjective ἠθικός denoting someone or something that relates to disposition, e.g., a philosophical study on character.[1] 2 Ethics is concerned with what is good for individuals and society. It involves developing, systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behaviour. The Hippocratic Oath (c. -

The Implications of Religious Beliefs on Medical and Patient Care

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Master of Science in Organizational Dynamics Theses Organizational Dynamics Programs 11-14-2011 The Implications of Religious Beliefs on Medical and Patient Care Dana I. Al Husseini University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/od_theses_msod Al Husseini, Dana I., "The Implications of Religious Beliefs on Medical and Patient Care" (2011). Master of Science in Organizational Dynamics Theses. 46. https://repository.upenn.edu/od_theses_msod/46 Submitted to the Program of Organizational Dynamics in the Graduate Division of the School of Arts and Sciences in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Organizational Dynamics at the University of Pennsylvania Advisor: Adrian Tschoegl This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/od_theses_msod/46 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Implications of Religious Beliefs on Medical and Patient Care Abstract Throughout history and to this date in a continuously globalized world, monotheistic religions and medicine have caused numerous acrimonious debates especially in crucial moments of life and death. Medical and nursing staff working with patients from different religions in any country in the world must adhere to and respect those patients’ faiths and be aware of them to provide better patient care and in worst case scenarios, avoid litigation. Furthermore, this paper should not to be treated as an encyclopedic reference; it is merely a general overview into the three monotheistic faiths to alert professional healthcare staff of the possibility of a religious implication even if it contradicts their own concerns and points of views.