Manufacturing Consent Thirty Years Later

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jus Cogens As a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr

Penn State International Law Review Volume 29 Article 2 Number 2 Penn State International Law Review 9-1-2010 Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Petsche, Dr. Markus (2010) "Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 29: No. 2, Article 2. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol29/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Articles I Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche* Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .............................................. 235 I. THE INAPPROPRIATENESS OF CHARACTERIZING JUS COGENS AS A RULE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE LIMITED RELEVANCE OF JUS COGENS FOR THE PRACTICE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW...................................238 A. FundamentalConceptual and Theoretical Flaws ofJus Cogens .................................... 238 1. Origins of Jus Cogens. .................. ..... 238 2. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking Substance........ 242 3. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Procedure for Its Determination. ............ ......... .......... 243 4. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Proper Theoretical Basis.......................... 245 B. The Limited Relevance of Jus Cogens for the Law of Treaties: Rare and Unsuccessful Reliance on Jus * DEA (Paris 1); LL.M. (NYU); Ph.D. -

Four Sociologies, Multiple Roles

The British Journal of Sociology 2005 Volume 56 Issue 3 Four sociologies, multiple roles Stella R. Quah The current American and British debate on public sociology introduced by Michael Burawoy in his 2004 ASA Presidential Address (Burawoy 2005) has inadvertently brought to light once again, one exciting but often overlooked aspect of our discipline: its geographical breadth.1 Sociology is present today in more countries around the world than ever before. Just as in the case of North America and Europe, Sociology’s presence in the rest of the world is manifested in many ways but primarily through the scholarly and policy- relevant work of research institutes, academic departments and schools in universities; through the training of new generations of sociologists in univer- sities; and through the work of individual sociologists in the private sector or the civil service. Michael Burawoy makes an important appeal for public sociology ‘not to be left out in the cold but brought into the framework of our discipline’ (2005: 4). It is the geographical breadth of Sociology that provides us with a unique vantage point to discuss his appeal critically. And, naturally, it is the geo- graphical breadth of sociology that makes Burawoy’s Presidential Address to the American Sociological Association relevant to sociologists outside the USA. Ideas relevant to all sociologists What has Michael Burawoy proposed that is most relevant to sociologists beyond the USA? He covers such an impressive range of aspects of the dis- cipline that it is not possible to address all of them here. Thus, thinking in terms of what resonates most for sociologists in different locations throughout the geographical breadth of the discipline, I believe his analytical approach and his call for integration deserve special attention. -

Libertarianism, Culture, and Personal Predispositions

Undergraduate Journal of Psychology 22 Libertarianism, Culture, and Personal Predispositions Ida Hepsø, Scarlet Hernandez, Shir Offsey, & Katherine White Kennesaw State University Abstract The United States has exhibited two potentially connected trends – increasing individualism and increasing interest in libertarian ideology. Previous research on libertarian ideology found higher levels of individualism among libertarians, and cross-cultural research has tied greater individualism to making dispositional attributions and lower altruistic tendencies. Given this, we expected to observe positive correlations between the following variables in the present research: individualism and endorsement of libertarianism, individualism and dispositional attributions, and endorsement of libertarianism and dispositional attributions. We also expected to observe negative correlations between libertarianism and altruism, dispositional attributions and altruism, and individualism and altruism. Survey results from 252 participants confirmed a positive correlation between individualism and libertarianism, a marginally significant positive correlation between libertarianism and dispositional attributions, and a negative correlation between individualism and altruism. These results confirm the connection between libertarianism and individualism observed in previous research and present several intriguing questions for future research on libertarian ideology. Key Words: Libertarianism, individualism, altruism, attributions individualistic, made apparent -

Indigenous and Tribal People's Rights Over Their Ancestral Lands

INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 56/09 30 December 2009 Original: Spanish INDIGENOUS AND TRIBAL PEOPLES’ RIGHTS OVER THEIR ANCESTRAL LANDS AND NATURAL RESOURCES Norms and Jurisprudence of the Inter‐American Human Rights System 2010 Internet: http://www.cidh.org E‐mail: [email protected] OAS Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data Derechos de los pueblos indígenas y tribales sobre sus tierras ancestrales y recursos naturales: Normas y jurisprudencia del sistema interamericano de derechos humanos = Indigenous and tribal people’s rights over their ancestral lands and natural resources: Norms and jurisprudence of the Inter‐American human rights system / [Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights.] p. ; cm. (OEA documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L)(OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978‐0‐8270‐5580‐3 1. Human rights‐‐America. 2. Indigenous peoples‐‐Civil rights‐‐America. 3. Indigenous peoples‐‐Land tenure‐‐America. 4. Indigenous peoples‐‐Legal status, laws, etc.‐‐America. 5. Natural resources‐‐Law and legislation‐‐America. I. Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. II Series. III. Series. OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.56/09 Document published thanks to the financial support of Denmark and Spain Positions herein expressed are those of the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights and do not reflect the views of Denmark or Spain Approved by the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights on December 30, 2009 INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS MEMBERS Luz Patricia Mejía Guerrero Víctor E. Abramovich Felipe González Sir Clare Kamau Roberts Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro Florentín Meléndez Paolo G. Carozza ****** Executive Secretary: Santiago A. -

Reflections on Social Norms and Human Rights

The Psychology of Social Norms and the Promotion of Human Rights Deborah A. Prentice Princeton University Chapter to appear in R. Goodman, D. Jinks, & A. K. Woods (Eds.), Understanding social action, promoting human rights. New York: Oxford University Press. This chapter was written while I was Visiting Faculty in the School of Social Sciences at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, NJ. I would like to thank Jeremy Adelman, JoAnne Gowa, Bob Keohane, Eric Maskin, Dale Miller, Catherine Ross, Teemu Ruskola, Rick Shweder, and Eric Weitz for helpful discussions and comments on earlier drafts of the chapter. Please direct correspondence to: Deborah Prentice Department of Psychology Princeton University Green Hall Princeton, NJ 08540 [email protected] 1 Promoting human rights means changing behavior: Changing the behavior of governments that mistreat suspected criminals, opponents of their policies, supporters of their political rivals, and members of particular gender, ethnic, or religious groups; changing the behavior of corporations that mistreat their workers, damage the environment, and produce unsafe products; and changing the behavior of citizens who mistreat their spouses, children, and neighbors. In this chapter, I consider what an understanding of how social norms function psychologically has to contribute to this very worthy project. Social norms have proven to be an effective mechanism for changing health-related and environmental behaviors, so there is good reason to think that they might be helpful in the human-rights domain as well. In the social sciences, social norms are defined as socially shared and enforced attitudes specifying what to do and what not to do in a given situation (see Elster, 1990; Sunstein, 1997). -

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don't Have Sex Without Them

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don’t Have Sex Without Them A Lesson Plan from Rights, Respect, Responsibility: A K-12 Curriculum Fostering responsibility by respecting young people’s rights to honest sexuality education. ADVANCE PREPARATION FOR LESSON: NSES ALIGNMENT: • Download the YouTube video on consent, “2 Minutes Will By the end of 12th grade, Change the Way You Think About Consent,” at https://www. students will be able to: youtube.com/watch?v=laMtr-rUEmY. HR.12.CC.3 – Define sexual consent and explain its • Also download the trailer for Pitch Perfect 2 - The Ellen Show implications for sexual decision- version (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBwOYQd21TY), making. queuing it up to play a brief clip between 2:10 and 2:27. PS.12.CC.3 – Explain why using tricks, threats or coercion in • If you cannot download and save these to your desktop in relationships is wrong. advance, talk with your school’s IT person to ensure you have HR.12.INF.2 – Analyze factors, internet access to that link during class. including alcohol and other substances, that can affect the • Print out the skit scenarios and cut out each pair, making sure ability to give or perceive the the correct person 1 goes with the correct person 2. Determine provision of consent to sexual how many pairs there will be in your class and make several activity. copies of each scenario, enough for each pair to get one. TARGET GRADE: Grade 10 LEARNING OBJECTIVES: Lesson 1 By the end of this lesson, students will be able to: 1. -

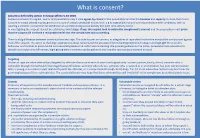

What Is Consent?

What is consent? Consent is defined by section 74 Sexual Offences Act 2003. Someone consents to vaginal, anal or oral penetration only if s/he agrees by choice to that penetration and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice. Consent to sexual activity may be given to one sort of sexual activity but not another, e.g.to vaginal but not anal sex or penetration with conditions, such as wearing a condom. Consent can be withdrawn at any time during sexual activity and each time activity occurs. In investigating the suspect, it must be established what steps, if any, the suspect took to obtain the complainant’s consent and the prosecution must prove that the suspect did not have a reasonable belief that the complainant was consenting. There is a big difference between consensual sex and rape. This aide focuses on consent, as allegations of rape often involve the word of the complainant against that of the suspect. The aim is to challenge assumptions about consent and the associated victim-blaming myths/stereotypes and highlight the suspect’s behaviour and motives to prove he did not reasonably believe the victim was consenting. We provide guidance to the police, prosecutors and advocates to identify and explain the differences, highlighting where evidence can be gathered and how the case can be presented in court. Targeting Victims of rape are often selected and targeted by offenders because of ease of access and opportunity - current partner, family, friend, someone who is vulnerable through mental health/ learning/physical difficulties, someone who sells sex, someone who is isolated or in an institution, has poor communication skills, is young, in a current or past relationship with the offender, or is compromised through drink/drugs. -

Addressing Fundamentalism by Legal and Spiritual Means

H UMAN R IGHTS & H UMAN W ELFARE Addressing Fundamentalism by Legal and Spiritual Means By Dan Wessner Religion and Humane Global Governance by Richard A. Falk. New York: Palgrave, 2001. 191 pp. Gender and Human Rights in Islam and International Law: Equal before Allah, Unequal before Man? by Shaheen Sardar Ali. The Hague: Kluwer Law International, 2000. 358 pp. Religious Fundamentalisms and the Human Rights of Women edited by Courtney W. Howland. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999. 326 pp. The Islamic Quest for Democracy, Pluralism, and Human Rights by Ahmad S. Moussalli. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2001. 226 pp. The post-Cold War era stands at a crossroads. Some sort of new world order or disorder is under construction. Our choice to move more toward multilateralism or unilateralism is informed well by inter-religious debate and international law. Both disciplines rightly challenge the “post- Enlightenment divide between religion and politics,” and reinvigorate a spiritual-legal dialogue once thought to be “irrelevant or substandard” (Falk: 1-8, 101). These disciplines can dissemble illusory walls between spiritual/sacred and material/modernist concerns, between realpolitik interests and ethical judgment (Kung 1998: 66). They place praxis and war-peace issues firmly in the context of a suffering humanity and world. Both warn as to how fundamentalism may subjugate peace and security to a demagogic, uncompromising quest. These disciplines also nurture a community of speech that continues to find its voice even as others resort to war. The four books considered in this essay respond to the rush and risk of unnecessary conflict wrought by fundamentalists. -

Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies

future internet Review Trust, but Verify: Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies Brian Pickering IT Innovation, Electronics and Computing, University of Southampton, University Road, Southampton SO17 1BJ, UK; [email protected] Abstract: To use technology or engage with research or medical treatment typically requires user consent: agreeing to terms of use with technology or services, or providing informed consent for research participation, for clinical trials and medical intervention, or as one legal basis for processing personal data. Introducing AI technologies, where explainability and trustworthiness are focus items for both government guidelines and responsible technologists, imposes additional challenges. Understanding enough of the technology to be able to make an informed decision, or consent, is essential but involves an acceptance of uncertain outcomes. Further, the contribution of AI- enabled technologies not least during the COVID-19 pandemic raises ethical concerns about the governance associated with their development and deployment. Using three typical scenarios— contact tracing, big data analytics and research during public emergencies—this paper explores a trust- based alternative to consent. Unlike existing consent-based mechanisms, this approach sees consent as a typical behavioural response to perceived contextual characteristics. Decisions to engage derive from the assumption that all relevant stakeholders including research participants will negotiate on an ongoing basis. Accepting dynamic negotiation between the main stakeholders as proposed here introduces a specifically socio–psychological perspective into the debate about human responses Citation: Pickering, B. Trust, but to artificial intelligence. This trust-based consent process leads to a set of recommendations for the Verify: Informed Consent, AI ethical use of advanced technologies as well as for the ethical review of applied research projects. -

Rethinking Burawoy's Public Sociology: a Post-Empiricist Critique." in the Handbook of Public Sociology, Edited by Vincent Jeffries, 47-70

Morrow, Raymond A. "Rethinking Burawoy's Public Sociology: A Post-Empiricist Critique." In The Handbook of Public Sociology, edited by Vincent Jeffries, 47-70. Lantham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2009. 3 Rethinking Burawoy’s Public Sociology: A Post-Empiricist Reconstruction Raymond A. Morrow Following Michael Burawoy’s ASA presidential address in August 2004, “For Public Sociology,” an unprecedented international debate has emerged on the current state and future of sociology (Burawoy 2005a). The goal here will be to provide a stock-taking of the resulting commentary that will of- fer some constructive suggestions for revising and reframing the original model. The central theme of discussion will be that while Burawoy’s mani- festo is primarily concerned with a plea for the institutionalization of pub- lic sociology, it is embedded in a very ambitious social theoretical frame- work whose full implications have not been worked out in sufficient detail (Burawoy 2005a). The primary objective of this essay will be to highlight such problems in the spirit of what Saskia Sassen calls “digging” to “detect the lumpiness of what seems an almost seamless map” (Sassen 2005:401) and to provide suggestions for constructive alternatives. Burawoy’s proposal has enjoyed considerable “political” success: “Bura- woy’s public address is, quite clearly, a politician’s speech—designed to build consensus and avoid ruffling too many feathers” (Hays 2007:80). As Patricia Hill Collins puts it, the eyes of many students “light up” when the schema is presented: “There’s the aha factor at work. They reso- nate with the name public sociology. Wishing to belong to something bigger than themselves” (Collins 2007:110–111). -

A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2006 Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language Michael Alan Glassco Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Glassco, Michael Alan, "Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language" (2006). Master's Theses. 4187. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4187 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEMOCRACY, HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIA TED LANGUAGE by Michael Alan Glassco A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College in partial fulfillment'of the requirements for the Degreeof Master of Arts School of Communication WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 2006 © 2006 Michael Alan Glassco· DEMOCRACY,HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIATED LANGUAGE Michael Alan Glassco, M.A. WesternMichigan University, 2006 Accepting and incorporating mediated political discourse into our everyday lives without conscious attention to the language used perpetuates the underlying ideological assumptions of power guiding such discourse. The consequences of such overreaching power are manifestin the public sphere as a hegemonic system in which freemarket capitalism is portrayed as democratic and necessaryto serve the needs of the public. This thesis focusesspecifically on two versions of the Society of ProfessionalJournalist Codes of Ethics 1987 and 1996, thought to influencethe output of news organizations. -

Political Ideology Chapter 9: Political Ideology|183

CHAPTER 9: Political Ideology Chapter 9: Political Ideology|183 "Aconservativeisaman withtwoperfectlygood legswho,however,has neverlearnedhowto walkforward." FranklinDelano Roosevelt, 32ndPresidentofthe UnitedStates “Thetroublewithour liberalfriendsisnotthat theyareignorant,but thattheyknowsomuch thatisn'tso.” 9.0 | What’s in a Name? RonaldReagan, 40thPresidentofthe Have you ever been in a discussion, debate, or perhaps even a heated UnitedStates argument about government or politics where one person objected to another person’s claim by saying, “That’s not what I mean by conservative (or liberal)? If so, then join the club. People often have to stop in the middle of a good political discussion when it becomes clear that the participants do not agree on the meanings of the terms that are central to the discussion. This can be the case with ideology because people often use familiar terms such as conservative, liberal, or socialist without agreeing on their meanings. This chapter has three main goals. The first goal is to explain the role ideology plays in modern political systems. The second goal is to define the major American ideologies: conservatism, liberalism, and libertarianism. The primary focus is on modern conservatism and liberalism. The third goal is to explain their role in government and politics. Some attention is also paid to other “isms”—belief systems that have some of the attributes of an ideology—that are relevant to modern American politics such as environmentalism, feminism, terrorism, and fundamentalism. The chapter begins with an examination of ideologies in general. It then examines American conservatism, liberalism, and other belief systems relevant to modern American politics and government. 9.1 | What is an ideology? An ideology is a belief system that consists of a relatively coherent set of ideas, attitudes, or values about government and politics, AND the public policies that are designed to implement the values or achieve the goals.