Informed Consent: Its Origin, Purpose, Problems, and Limits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jus Cogens As a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr

Penn State International Law Review Volume 29 Article 2 Number 2 Penn State International Law Review 9-1-2010 Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Petsche, Dr. Markus (2010) "Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 29: No. 2, Article 2. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol29/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Articles I Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche* Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .............................................. 235 I. THE INAPPROPRIATENESS OF CHARACTERIZING JUS COGENS AS A RULE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE LIMITED RELEVANCE OF JUS COGENS FOR THE PRACTICE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW...................................238 A. FundamentalConceptual and Theoretical Flaws ofJus Cogens .................................... 238 1. Origins of Jus Cogens. .................. ..... 238 2. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking Substance........ 242 3. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Procedure for Its Determination. ............ ......... .......... 243 4. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Proper Theoretical Basis.......................... 245 B. The Limited Relevance of Jus Cogens for the Law of Treaties: Rare and Unsuccessful Reliance on Jus * DEA (Paris 1); LL.M. (NYU); Ph.D. -

Indigenous and Tribal People's Rights Over Their Ancestral Lands

INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 56/09 30 December 2009 Original: Spanish INDIGENOUS AND TRIBAL PEOPLES’ RIGHTS OVER THEIR ANCESTRAL LANDS AND NATURAL RESOURCES Norms and Jurisprudence of the Inter‐American Human Rights System 2010 Internet: http://www.cidh.org E‐mail: [email protected] OAS Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data Derechos de los pueblos indígenas y tribales sobre sus tierras ancestrales y recursos naturales: Normas y jurisprudencia del sistema interamericano de derechos humanos = Indigenous and tribal people’s rights over their ancestral lands and natural resources: Norms and jurisprudence of the Inter‐American human rights system / [Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights.] p. ; cm. (OEA documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L)(OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978‐0‐8270‐5580‐3 1. Human rights‐‐America. 2. Indigenous peoples‐‐Civil rights‐‐America. 3. Indigenous peoples‐‐Land tenure‐‐America. 4. Indigenous peoples‐‐Legal status, laws, etc.‐‐America. 5. Natural resources‐‐Law and legislation‐‐America. I. Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. II Series. III. Series. OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.56/09 Document published thanks to the financial support of Denmark and Spain Positions herein expressed are those of the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights and do not reflect the views of Denmark or Spain Approved by the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights on December 30, 2009 INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS MEMBERS Luz Patricia Mejía Guerrero Víctor E. Abramovich Felipe González Sir Clare Kamau Roberts Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro Florentín Meléndez Paolo G. Carozza ****** Executive Secretary: Santiago A. -

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don't Have Sex Without Them

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don’t Have Sex Without Them A Lesson Plan from Rights, Respect, Responsibility: A K-12 Curriculum Fostering responsibility by respecting young people’s rights to honest sexuality education. ADVANCE PREPARATION FOR LESSON: NSES ALIGNMENT: • Download the YouTube video on consent, “2 Minutes Will By the end of 12th grade, Change the Way You Think About Consent,” at https://www. students will be able to: youtube.com/watch?v=laMtr-rUEmY. HR.12.CC.3 – Define sexual consent and explain its • Also download the trailer for Pitch Perfect 2 - The Ellen Show implications for sexual decision- version (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBwOYQd21TY), making. queuing it up to play a brief clip between 2:10 and 2:27. PS.12.CC.3 – Explain why using tricks, threats or coercion in • If you cannot download and save these to your desktop in relationships is wrong. advance, talk with your school’s IT person to ensure you have HR.12.INF.2 – Analyze factors, internet access to that link during class. including alcohol and other substances, that can affect the • Print out the skit scenarios and cut out each pair, making sure ability to give or perceive the the correct person 1 goes with the correct person 2. Determine provision of consent to sexual how many pairs there will be in your class and make several activity. copies of each scenario, enough for each pair to get one. TARGET GRADE: Grade 10 LEARNING OBJECTIVES: Lesson 1 By the end of this lesson, students will be able to: 1. -

What Is Consent?

What is consent? Consent is defined by section 74 Sexual Offences Act 2003. Someone consents to vaginal, anal or oral penetration only if s/he agrees by choice to that penetration and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice. Consent to sexual activity may be given to one sort of sexual activity but not another, e.g.to vaginal but not anal sex or penetration with conditions, such as wearing a condom. Consent can be withdrawn at any time during sexual activity and each time activity occurs. In investigating the suspect, it must be established what steps, if any, the suspect took to obtain the complainant’s consent and the prosecution must prove that the suspect did not have a reasonable belief that the complainant was consenting. There is a big difference between consensual sex and rape. This aide focuses on consent, as allegations of rape often involve the word of the complainant against that of the suspect. The aim is to challenge assumptions about consent and the associated victim-blaming myths/stereotypes and highlight the suspect’s behaviour and motives to prove he did not reasonably believe the victim was consenting. We provide guidance to the police, prosecutors and advocates to identify and explain the differences, highlighting where evidence can be gathered and how the case can be presented in court. Targeting Victims of rape are often selected and targeted by offenders because of ease of access and opportunity - current partner, family, friend, someone who is vulnerable through mental health/ learning/physical difficulties, someone who sells sex, someone who is isolated or in an institution, has poor communication skills, is young, in a current or past relationship with the offender, or is compromised through drink/drugs. -

Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies

future internet Review Trust, but Verify: Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies Brian Pickering IT Innovation, Electronics and Computing, University of Southampton, University Road, Southampton SO17 1BJ, UK; [email protected] Abstract: To use technology or engage with research or medical treatment typically requires user consent: agreeing to terms of use with technology or services, or providing informed consent for research participation, for clinical trials and medical intervention, or as one legal basis for processing personal data. Introducing AI technologies, where explainability and trustworthiness are focus items for both government guidelines and responsible technologists, imposes additional challenges. Understanding enough of the technology to be able to make an informed decision, or consent, is essential but involves an acceptance of uncertain outcomes. Further, the contribution of AI- enabled technologies not least during the COVID-19 pandemic raises ethical concerns about the governance associated with their development and deployment. Using three typical scenarios— contact tracing, big data analytics and research during public emergencies—this paper explores a trust- based alternative to consent. Unlike existing consent-based mechanisms, this approach sees consent as a typical behavioural response to perceived contextual characteristics. Decisions to engage derive from the assumption that all relevant stakeholders including research participants will negotiate on an ongoing basis. Accepting dynamic negotiation between the main stakeholders as proposed here introduces a specifically socio–psychological perspective into the debate about human responses Citation: Pickering, B. Trust, but to artificial intelligence. This trust-based consent process leads to a set of recommendations for the Verify: Informed Consent, AI ethical use of advanced technologies as well as for the ethical review of applied research projects. -

Human Challenge Trials for Vaccine Development: Regulatory Considerations

POST ECBS Version ENGLISH ONLY EXPERT COMMITTEE ON BIOLOGICAL STANDARDIZATION Geneva, 17 to 21 October 2016 Human Challenge Trials for Vaccine Development: regulatory considerations © World Health Organization 2016 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; email: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. -

Informed Consent and Refusal

CHAPTER 3 Informed Consent and Refusal Evolution of the doctrine of informed consent Elements of informed consent and refusal The nature of informed consent Exceptions to the consent requirement Mrs. Stack is a 67- year- old woman admitted with rectal bleeding, chronic renal in- sufficiency, diabetes, and blindness. On admission, she was alert and capacitated. Two weeks later, she suffered a cardiopulmonary arrest, was resuscitated and intu- bated, and was transferred to the medical intensive care unit (MICU) in an unrespon- sive and unstable state. Consent for emergency dialysis was obtained from her son, who is also her health care agent. Dialysis was repeated two days later. During the past several years, Mrs. Stack has consistently stated to her family and her primary care doctor that she would never want to be on chronic dialysis and she has refused it numerous times when it was recommended. The physician, who has known and treated Mrs. Stack for many years, also treated her daughter who had been on chronic dialysis for some time and had died after suffering a heart attack. According to the physician and the patient’s family, Mrs. Stack’s refusal of dialysis has been based on her conviction that her daughter died as a result of the dialysis treatments. Mrs. Stack’s mental status has cleared considerably and, despite the ventilator, she is able to communicate nonverbally. Although she appears to understand the benefits of dialysis and the consequences of refusing it, including deterioration and eventual death, she has consistently and vehemently refused further treatments. Her capacity to make this decision is not now in question. -

The Implications of Religious Beliefs on Medical and Patient Care

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Master of Science in Organizational Dynamics Theses Organizational Dynamics Programs 11-14-2011 The Implications of Religious Beliefs on Medical and Patient Care Dana I. Al Husseini University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/od_theses_msod Al Husseini, Dana I., "The Implications of Religious Beliefs on Medical and Patient Care" (2011). Master of Science in Organizational Dynamics Theses. 46. https://repository.upenn.edu/od_theses_msod/46 Submitted to the Program of Organizational Dynamics in the Graduate Division of the School of Arts and Sciences in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Organizational Dynamics at the University of Pennsylvania Advisor: Adrian Tschoegl This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/od_theses_msod/46 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Implications of Religious Beliefs on Medical and Patient Care Abstract Throughout history and to this date in a continuously globalized world, monotheistic religions and medicine have caused numerous acrimonious debates especially in crucial moments of life and death. Medical and nursing staff working with patients from different religions in any country in the world must adhere to and respect those patients’ faiths and be aware of them to provide better patient care and in worst case scenarios, avoid litigation. Furthermore, this paper should not to be treated as an encyclopedic reference; it is merely a general overview into the three monotheistic faiths to alert professional healthcare staff of the possibility of a religious implication even if it contradicts their own concerns and points of views. -

Informed Consent

Christine Grady Department of Bioethics NIH Clinical Center The views expressed here are mine and do not necessarily represent those of the CC, NIH, or Department of Health and Human Services Informed consent is the bedrock principle on which most of modern research ethics rest…This was at the heart of the crucial ethical provision stated in the first words of the Nuremberg Code, and it remains equally compelling a half century later. Menikoff J, Camb Quarterly 2004 p 342 Authorization of an activity based on understanding what the activity entails. A legal, regulatory, and ethical requirement in health care and in most research with human subjects A process of reasoned decision making (not a form or an episode) One aspect of conducting ethical clinical research “Every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what will be done with his body… Justice Cardozo, 1914 Respect for autonomy or for an individual’s capacity and right to define own goals and make choices consistent with those goals. Well entrenched in American values, jurisprudence, medical practice, and clinical research. “Informed consent is rooted in the fundamental recognition…that adults are entitled to accept or reject health care interventions on the basis of their own personal values and in furtherance of their own personal goals” Presidents Commission for the study of ethical problems…1982 Informed consent in medical practice …informed consent in clinical practice is frequently inadequate… Physicians receive little training… Misunderstand requirements and legal standards… Time pressures and competing demands… Patient comprehension is often poor… Recent studies have demonstrated improvement in patient understanding of risks after communication interventions Schenker et al 2010; Matiasek et al. -

Informed Consent for Participation in Personal Training

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY Personal Training INFORMED CONSENT FOR PARTICIPATION IN PERSONAL TRAINING Name: ________________________ 1. Purpose and Explanation of Procedure I desire to participate voluntarily in an acceptable plan of exercise conditioning. I also desire to be placed in program activities which are recommended to me for improvement of my general health and well-being in which I will be given exact instructions regarding the amount and kind of exercise I should do. Professionally trained personnel will provide leadership to direct my activities, monitor my performance and otherwise evaluate my effort. Depending upon my health status, I may or may not be required to have my heart rate evaluated during these sessions and/or regulate my exercise within desired limits. I understand that I am expected to follow staff instructions with regard to the proper performance of each exercise. I have been advised and understand it is recommended that I obtain a medical examination by a physician before I participate in this program. The medical examination is highly suggested in order to identify conditions which may preclude participation. If I am taking prescribed medications, I have already so informed the program staff and further agree to inform them promptly of any changes which my doctor or I may make with regard to such use. I have been informed that during my participation in exercise, I will be asked to complete the physical activities unless such symptoms as fatigue, shortness of breath, chest discomfort or similar occurrences appear. At that point, I have been advised it is my complete right and responsibility to decrease or stop exercising and that it is my obligation to inform the program personnel of my symptoms. -

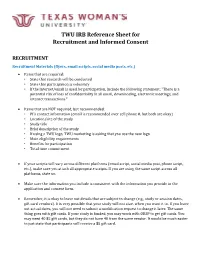

TWU IRB Reference Sheet for Recruitment and Informed Consent

TWU IRB Reference Sheet for Recruitment and Informed Consent RECRUITMENT Recruitment Materials (flyers, email scripts, social media posts, etc.) • Items that are required: • State that research will be conducted • State that participation is voluntary • If the internet/email is used for participation, include the following statement: “There is a potential risk of loss of confidentiality in all email, downloading, electronic meetings, and internet transactions.” • Items that are NOT required, but recommended: • PI’s contact information (email is recommended over cell phone #, but both are okay) • Location/site of the study • Study title • Brief description of the study • If using a TWU logo, TWU marketing is asking that you use the new logo • Main eligibility requirements • Benefits for participation • Total time commitment • If your scripts will vary across different platforms (email script, social media post, phone script, etc.), make sure you attach all appropriate scripts. If you are using the same script across all platforms, state so. • Make sure the information you include is consistent with the information you provide in the application and consent form. • Remember, it is okay to leave out details that are subject to change (e.g., study or session dates, gift card vendors). It is very possible that your study will not start when you want it to. If you leave out actual dates, you will not need to submit a modification request to change it later. The same thing goes with gift cards. If your study is funded, you may work with ORSP to get gift cards. You may need 40 $5 gift cards, but they do not have 40 from the same vendor. -

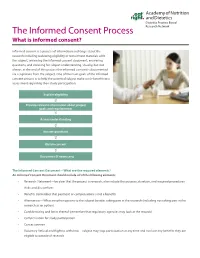

The Informed Consent Process Research Network What Is Informed Consent?

Dietetics Practice Based The Informed Consent Process Research Network What is informed consent? Informed consent is a process of information exchange about the research including reviewing eligibility or recruitment materials with the subject, reviewing the informed consent document, answering questions, and checking for subject understanding. Usually, but not always, at the end of this process the informed consent is documented via a signature from the subject. One of the main goals of the informed consent process is to help the potential subject make a risk-benefit ratio assessment regarding their study participation. Explain eligibility Provide relevant information about project goals and requirements Assess understanding Answer questions Obtain consent Document (if necessary) The Informed Consent Document—What are the required elements? An Informed Consent Document should include all of the following elements: • Research Statement—be clear that the project is research, also include the purpose, duration, and required procedures • Risks and discomforts • Benefits (remember that payment or compensation is not a benefit) • Alternatives—What are other options to the subject besides taking part in the research (including not taking part in the research as an option) • Confidentiality and limits thereof (remember that regulatory agencies may look at the records) • Compensation for study participation • Contact person • Voluntary Refusal and Right to withdraw—subject may stop participation at any time and not lose any benefits they are