Manufacturing Consent an Investigation of the Press Support Towards the US Administration Prior to US-Led Airstrikes in Syria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extract from Public Opinion by Walter Lippmann Concerning

1 WALTER LIPPMANN - EXTRACT FROM PUBLIC OPINION BY WALTER LIPPMANN CONCERNING MANUFACTURING CONSENT PUBLISHED 1922 “Public Opinion is a book by Walter Lippmann, published in 1922. It is a critical assessment of functional democratic government, especially of the irrational and often self-serving social perceptions that influence individual behavior and prevent optimal societal cohesion.[1] The detailed descriptions of the cognitive limitations people face in comprehending their sociopolitical and cultural environments, leading them to apply an evolving catalogue of general stereotypes to a complex reality, rendered Public Opinion a seminal text in the fields of media studies, political science, and social psychology.” WIKI. EXTRACT 4 That the manufacture of consent is capable of great refinements no one, I think, denies. The process by which public opinions arise is certainly no less intricate than it has appeared in these pages, and the opportunities for manipulation open to anyone who understands the process are plain enough. The creation of consent is not a new art. It is a very old one which was supposed to have died out with the appearance of democracy. But it has not died out. It has, in fact, improved enormously in technic, because it is now based on analysis rather than on rule of thumb. And so, as a result of psychological research, coupled with the modern means of communication, the practice of democracy has turned a corner. A revolution is taking place, infinitely more significant than any shifting of economic power. Within the life of the generation now in control of affairs, persuasion has become a self-conscious art and a regular organ of popular government. -

Jus Cogens As a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr

Penn State International Law Review Volume 29 Article 2 Number 2 Penn State International Law Review 9-1-2010 Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Petsche, Dr. Markus (2010) "Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 29: No. 2, Article 2. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol29/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Articles I Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche* Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .............................................. 235 I. THE INAPPROPRIATENESS OF CHARACTERIZING JUS COGENS AS A RULE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE LIMITED RELEVANCE OF JUS COGENS FOR THE PRACTICE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW...................................238 A. FundamentalConceptual and Theoretical Flaws ofJus Cogens .................................... 238 1. Origins of Jus Cogens. .................. ..... 238 2. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking Substance........ 242 3. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Procedure for Its Determination. ............ ......... .......... 243 4. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Proper Theoretical Basis.......................... 245 B. The Limited Relevance of Jus Cogens for the Law of Treaties: Rare and Unsuccessful Reliance on Jus * DEA (Paris 1); LL.M. (NYU); Ph.D. -

Indigenous and Tribal People's Rights Over Their Ancestral Lands

INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 56/09 30 December 2009 Original: Spanish INDIGENOUS AND TRIBAL PEOPLES’ RIGHTS OVER THEIR ANCESTRAL LANDS AND NATURAL RESOURCES Norms and Jurisprudence of the Inter‐American Human Rights System 2010 Internet: http://www.cidh.org E‐mail: [email protected] OAS Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data Derechos de los pueblos indígenas y tribales sobre sus tierras ancestrales y recursos naturales: Normas y jurisprudencia del sistema interamericano de derechos humanos = Indigenous and tribal people’s rights over their ancestral lands and natural resources: Norms and jurisprudence of the Inter‐American human rights system / [Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights.] p. ; cm. (OEA documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L)(OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978‐0‐8270‐5580‐3 1. Human rights‐‐America. 2. Indigenous peoples‐‐Civil rights‐‐America. 3. Indigenous peoples‐‐Land tenure‐‐America. 4. Indigenous peoples‐‐Legal status, laws, etc.‐‐America. 5. Natural resources‐‐Law and legislation‐‐America. I. Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. II Series. III. Series. OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.56/09 Document published thanks to the financial support of Denmark and Spain Positions herein expressed are those of the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights and do not reflect the views of Denmark or Spain Approved by the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights on December 30, 2009 INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS MEMBERS Luz Patricia Mejía Guerrero Víctor E. Abramovich Felipe González Sir Clare Kamau Roberts Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro Florentín Meléndez Paolo G. Carozza ****** Executive Secretary: Santiago A. -

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don't Have Sex Without Them

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don’t Have Sex Without Them A Lesson Plan from Rights, Respect, Responsibility: A K-12 Curriculum Fostering responsibility by respecting young people’s rights to honest sexuality education. ADVANCE PREPARATION FOR LESSON: NSES ALIGNMENT: • Download the YouTube video on consent, “2 Minutes Will By the end of 12th grade, Change the Way You Think About Consent,” at https://www. students will be able to: youtube.com/watch?v=laMtr-rUEmY. HR.12.CC.3 – Define sexual consent and explain its • Also download the trailer for Pitch Perfect 2 - The Ellen Show implications for sexual decision- version (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBwOYQd21TY), making. queuing it up to play a brief clip between 2:10 and 2:27. PS.12.CC.3 – Explain why using tricks, threats or coercion in • If you cannot download and save these to your desktop in relationships is wrong. advance, talk with your school’s IT person to ensure you have HR.12.INF.2 – Analyze factors, internet access to that link during class. including alcohol and other substances, that can affect the • Print out the skit scenarios and cut out each pair, making sure ability to give or perceive the the correct person 1 goes with the correct person 2. Determine provision of consent to sexual how many pairs there will be in your class and make several activity. copies of each scenario, enough for each pair to get one. TARGET GRADE: Grade 10 LEARNING OBJECTIVES: Lesson 1 By the end of this lesson, students will be able to: 1. -

Personalizing Predictions of Video-Induced Emotions Using Personal Memories As Context

A Blast From the Past: Personalizing Predictions of Video-Induced Emotions using Personal Memories as Context Bernd Dudzik∗ Joost Broekens Delft University of Technology Delft University of Technology Delft, South Holland, The Netherlands Delft, South Holland, The Netherlands [email protected] [email protected] Mark Neerincx Hayley Hung Delft University of Technology Delft University of Technology Delft, South Holland, The Netherlands Delft, South Holland, The Netherlands [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT match a viewer’s current desires, e.g., to see an "amusing" video, A key challenge in the accurate prediction of viewers’ emotional these will likely need some sensitivity for the conditions under responses to video stimuli in real-world applications is accounting which any potential video will create this experience specifically for person- and situation-specific variation. An important contex- for him/her. Therefore, addressing variation in emotional responses tual influence shaping individuals’ subjective experience of avideo by personalizing predictions is a vital step for progressing VACA is the personal memories that it triggers in them. Prior research research (see the reviews by Wang et al. [68] and Baveye et al. [7]). has found that this memory influence explains more variation in Despite the potential benefits, existing research efforts still rarely video-induced emotions than other contextual variables commonly explore incorporating situation- or person-specific context to per- used for personalizing -

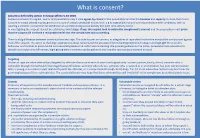

What Is Consent?

What is consent? Consent is defined by section 74 Sexual Offences Act 2003. Someone consents to vaginal, anal or oral penetration only if s/he agrees by choice to that penetration and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice. Consent to sexual activity may be given to one sort of sexual activity but not another, e.g.to vaginal but not anal sex or penetration with conditions, such as wearing a condom. Consent can be withdrawn at any time during sexual activity and each time activity occurs. In investigating the suspect, it must be established what steps, if any, the suspect took to obtain the complainant’s consent and the prosecution must prove that the suspect did not have a reasonable belief that the complainant was consenting. There is a big difference between consensual sex and rape. This aide focuses on consent, as allegations of rape often involve the word of the complainant against that of the suspect. The aim is to challenge assumptions about consent and the associated victim-blaming myths/stereotypes and highlight the suspect’s behaviour and motives to prove he did not reasonably believe the victim was consenting. We provide guidance to the police, prosecutors and advocates to identify and explain the differences, highlighting where evidence can be gathered and how the case can be presented in court. Targeting Victims of rape are often selected and targeted by offenders because of ease of access and opportunity - current partner, family, friend, someone who is vulnerable through mental health/ learning/physical difficulties, someone who sells sex, someone who is isolated or in an institution, has poor communication skills, is young, in a current or past relationship with the offender, or is compromised through drink/drugs. -

Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies

future internet Review Trust, but Verify: Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies Brian Pickering IT Innovation, Electronics and Computing, University of Southampton, University Road, Southampton SO17 1BJ, UK; [email protected] Abstract: To use technology or engage with research or medical treatment typically requires user consent: agreeing to terms of use with technology or services, or providing informed consent for research participation, for clinical trials and medical intervention, or as one legal basis for processing personal data. Introducing AI technologies, where explainability and trustworthiness are focus items for both government guidelines and responsible technologists, imposes additional challenges. Understanding enough of the technology to be able to make an informed decision, or consent, is essential but involves an acceptance of uncertain outcomes. Further, the contribution of AI- enabled technologies not least during the COVID-19 pandemic raises ethical concerns about the governance associated with their development and deployment. Using three typical scenarios— contact tracing, big data analytics and research during public emergencies—this paper explores a trust- based alternative to consent. Unlike existing consent-based mechanisms, this approach sees consent as a typical behavioural response to perceived contextual characteristics. Decisions to engage derive from the assumption that all relevant stakeholders including research participants will negotiate on an ongoing basis. Accepting dynamic negotiation between the main stakeholders as proposed here introduces a specifically socio–psychological perspective into the debate about human responses Citation: Pickering, B. Trust, but to artificial intelligence. This trust-based consent process leads to a set of recommendations for the Verify: Informed Consent, AI ethical use of advanced technologies as well as for the ethical review of applied research projects. -

Affective Image Content Analysis: a Comprehensive Survey∗

Proceedings of the Twenty-Seventh International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-18) Affective Image Content Analysis: A Comprehensive Survey∗ Sicheng Zhaoy, Guiguang Dingz, Qingming Huang], Tat-Seng Chuax, Bjorn¨ W. Schuller♦ and Kurt Keutzery yDepartment of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences, University of California, Berkeley, USA zSchool of Software, Tsinghua University, China ]School of Computer and Control Engineering, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, China xSchool of Computing, National University of Singapore, Singapore ♦Department of Computing, Imperial College London, UK Abstract Specifically, the task of AICA is often composed of three steps: human annotation, visual feature extraction and learn- Images can convey rich semantics and induce ing of mapping between visual features and perceived emo- strong emotions in viewers. Recently, with the ex- tions [Zhao et al., 2017a]. One main challenge for AICA is plosive growth of visual data, extensive research ef- the affective gap, which can be defined as “the lack of coinci- forts have been dedicated to affective image content dence between the features and the expected affective state in analysis (AICA). In this paper, we review the state- which the user is brought by perceiving the signal” [Hanjalic, of-the-art methods comprehensively with respect to 2006]. Recently, various hand-crafted or learning-based fea- two main challenges – affective gap and percep- tures have been designed to bridge this gap. Current AICA tion subjectivity. We begin with an introduction methods mainly assign an image with the dominant (average) to the key emotion representation models that have emotion category (DEC) with the assumption that different been widely employed in AICA. -

Noam Chomsky: Turning the Tide

NOAM CHOMSKY TURNING THE TIDE US Intervention in Central America and the Struggle for Peace ESSENTIAL CLASSICS IN POLITICS: NOAM CHOMSKY EB 0007 ISBN 0 7453 1345 0 London 1999 The Electric Book Company Ltd Pluto Press Ltd 20 Cambridge Drive 345 Archway Rd London SE12 8AJ, UK London N6 5AA, UK www.elecbook.com www.plutobooks.com © Noam Chomsky 1999 Limited printing and text selection allowed for individual use only. All other reproduction, whether by printing or electronically or by any other means, is expressly forbidden without the prior permission of the publishers. This file may only be used as part of the CD on which it was first issued. TURNING THE TIDE US Intervention in Central America and the Struggle for Peace Noam Chomsky 4 Copyright 1985 by Noam Chomsky Manufactured in the USA Production at South End Press, Boston Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data Chomsky, Noam Turning the tide. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Central America—Politics and government—1979- . 2. Violence—Central America—History—20th century. 3. Civil rights—Central America—History—20th century. 4. Central America—Foreign relations—United States. 5. United States— Foreign relations—Central America. I. Title F1 436. 8. U6 1985 327. 728073 ISBN: 0-7453-0184-3 Digital processing by The Electric Book Company 20 Cambridge Drive, London SE12 8AJ, UK www.elecbook.com Classics in Politics: Turning the Tide Noam Chomsky 5 Contents Click on number to go to page Introduction................................................................................. 8 1. Free World Vignettes .............................................................. 11 1. The Miseries of Traditional Life.............................................. 15 2. Challenge and Response: Nicaragua...................................... -

Samantha Smith How Can Herman and Chomsky's Ideas Function in A

Samantha Smith How can Herman and Chomsky’s Ideas Function in a Post-communist World? How can Herman and Chomsky’s Ideas Function in a Post-communist World? is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. This publication may be cited as: Samantha Smith. (2017). How can Herman and Chomsky’s Ideas Function in a Post- communist World?. Pūrātoke: Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Creative Arts and Industries, 1(1), 147-154. Founded at Unitec Institute of Technology in 2017 ISSN 2538-0133 An ePress publication [email protected] www.unitec.ac.nz/epress/ Unitec Institute of Technology Private Bag 92025 Victoria Street West Auckland 1010 Aotearoa New Zealand 148 SAMANTHA SMITH HOW CAN HERMAN AND CHOMSKY’S IDEAS FUNCTION IN A POST-COMMUNIST WORLD? Abstract This essay discusses the opportunity for Herman and Chomsky’s propaganda model, as outlined in their book, Manufacturing Consent (1988), to be altered to remain relevant in a post-communist world. The model previously described five filters, which influence the US media, causing them to stray somewhat from their role as the fourth estate, and preventing them from upholding the ideals of democracy. These filters included ownership, advertising, sourcing, flak and anti-communism. But with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the threat of communism diminished and a new threat emerged. Since September 11, the war on terrorism has become a focus in the US media, creating a new hysteria. In Herman and Chomsky’s propaganda model, anti-communism can be replaced with terrorism to prolong its functionality in a post-communist world. -

Thematic Content Analysis (TCA) 1 Descriptive Presentation of Qualitative Data

Thematic Content Analysis (TCA) 1 Descriptive Presentation of Qualitative Data Rosemarie Anderson, PhD 2 Professor, Institute of Transpersonal Psychology (www.itp.edu) Consultant, Wellknowing Consulting (www.wellknowingconsulting.org) Introduction. Thematic Content Analysis (TCA) is a descriptive presentation of qualitative data. Qualitative data may take the form of interview transcripts collected from research participants or other identified texts that reflect experientially on the topic of study. While video, image, and other forms of data may accompany textural data, this description of TCA is limited to textural data. A number of software programs are available to automate the labeling and grouping of texts and are especially useful in the analysis of numerous transcripts. Generally speaking, though, Microsoft Word can be used effectively for most TCAs and the steps are described below. A satisfactory TCA portrays the thematic content of interview transcripts (or other texts) by identifying common themes in the texts provided for analysis. TCA is the most foundational of qualitative analytic procedures and in some way informs all qualitative methods. In conducting a TCA, the researcher’s epistemological stance is objective or objectivistic. In teaching Qualitative Research Methods, I describe TCA as a form of “low hovering” over the data. The researcher groups and distills from the texts a list of common themes in order to give expression to the communality of voices across participants. Every attempt reasonable is made to employ names for themes from the actual words of participants and to group themes in manner that directly reflects the texts as a whole. While sorting and naming themes requires some level of interpretation, “interpretation” is kept to a minimum. -

Teaching About Propaganda

R. Hobbs & S. McGee, Journal of Media Literacy Education 6(2), 56 - 67 Available online at www.jmle.org The National Association for Media Literacy Education’s Journal of Media Literacy Education 6(2), 56 - 67 Teaching about Propaganda: An Examination of the Historical Roots of Media Literacy Renee Hobbs and Sandra McGee Harrington School of Communication and Media, University of Rhode Island Abstract Contemporary propaganda is ubiquitous in our culture today as public relations and marketing efforts have become core dimensions of the contemporary communication system, affecting all forms of personal, social and public expression. To examine the origins of teaching and learning about propaganda, we examine some instructional materials produced in the 1930s by the Institute for Propaganda Analysis (IPA), which popularized an early form of media literacy that promoted critical analysis in responding to propaganda in mass communication, including in radio, film and newspapers. They developed study guides and distributed them widely, popularizing concepts from classical rhetoric and expressing them in an easy-to-remember way. In this paper, we compare the popular list of seven propaganda techniques (with terms like “glittering generalities” and “bandwagon”) to a less well-known list, the ABC’s of Propaganda Analysis. While the seven propaganda techniques, rooted in ancient rhetoric, have endured as the dominant approach to explore persuasion and propaganda in secondary English education, the ABC’s of Propaganda Analysis, with its focus on the practice of personal reflection and life history analysis, anticipates some of the core concepts and instructional practices of media literacy in the 21st century. Following from this insight, we see evidence of the value of social reflection practices for exploring propaganda in the context of formal and informal learning.