The Basis of International Law: Why Nations Observe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jus Cogens As a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr

Penn State International Law Review Volume 29 Article 2 Number 2 Penn State International Law Review 9-1-2010 Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Petsche, Dr. Markus (2010) "Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 29: No. 2, Article 2. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol29/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Articles I Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche* Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .............................................. 235 I. THE INAPPROPRIATENESS OF CHARACTERIZING JUS COGENS AS A RULE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE LIMITED RELEVANCE OF JUS COGENS FOR THE PRACTICE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW...................................238 A. FundamentalConceptual and Theoretical Flaws ofJus Cogens .................................... 238 1. Origins of Jus Cogens. .................. ..... 238 2. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking Substance........ 242 3. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Procedure for Its Determination. ............ ......... .......... 243 4. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Proper Theoretical Basis.......................... 245 B. The Limited Relevance of Jus Cogens for the Law of Treaties: Rare and Unsuccessful Reliance on Jus * DEA (Paris 1); LL.M. (NYU); Ph.D. -

Indigenous and Tribal People's Rights Over Their Ancestral Lands

INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 56/09 30 December 2009 Original: Spanish INDIGENOUS AND TRIBAL PEOPLES’ RIGHTS OVER THEIR ANCESTRAL LANDS AND NATURAL RESOURCES Norms and Jurisprudence of the Inter‐American Human Rights System 2010 Internet: http://www.cidh.org E‐mail: [email protected] OAS Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data Derechos de los pueblos indígenas y tribales sobre sus tierras ancestrales y recursos naturales: Normas y jurisprudencia del sistema interamericano de derechos humanos = Indigenous and tribal people’s rights over their ancestral lands and natural resources: Norms and jurisprudence of the Inter‐American human rights system / [Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights.] p. ; cm. (OEA documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L)(OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978‐0‐8270‐5580‐3 1. Human rights‐‐America. 2. Indigenous peoples‐‐Civil rights‐‐America. 3. Indigenous peoples‐‐Land tenure‐‐America. 4. Indigenous peoples‐‐Legal status, laws, etc.‐‐America. 5. Natural resources‐‐Law and legislation‐‐America. I. Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. II Series. III. Series. OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.56/09 Document published thanks to the financial support of Denmark and Spain Positions herein expressed are those of the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights and do not reflect the views of Denmark or Spain Approved by the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights on December 30, 2009 INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS MEMBERS Luz Patricia Mejía Guerrero Víctor E. Abramovich Felipe González Sir Clare Kamau Roberts Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro Florentín Meléndez Paolo G. Carozza ****** Executive Secretary: Santiago A. -

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don't Have Sex Without Them

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don’t Have Sex Without Them A Lesson Plan from Rights, Respect, Responsibility: A K-12 Curriculum Fostering responsibility by respecting young people’s rights to honest sexuality education. ADVANCE PREPARATION FOR LESSON: NSES ALIGNMENT: • Download the YouTube video on consent, “2 Minutes Will By the end of 12th grade, Change the Way You Think About Consent,” at https://www. students will be able to: youtube.com/watch?v=laMtr-rUEmY. HR.12.CC.3 – Define sexual consent and explain its • Also download the trailer for Pitch Perfect 2 - The Ellen Show implications for sexual decision- version (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBwOYQd21TY), making. queuing it up to play a brief clip between 2:10 and 2:27. PS.12.CC.3 – Explain why using tricks, threats or coercion in • If you cannot download and save these to your desktop in relationships is wrong. advance, talk with your school’s IT person to ensure you have HR.12.INF.2 – Analyze factors, internet access to that link during class. including alcohol and other substances, that can affect the • Print out the skit scenarios and cut out each pair, making sure ability to give or perceive the the correct person 1 goes with the correct person 2. Determine provision of consent to sexual how many pairs there will be in your class and make several activity. copies of each scenario, enough for each pair to get one. TARGET GRADE: Grade 10 LEARNING OBJECTIVES: Lesson 1 By the end of this lesson, students will be able to: 1. -

The Nature of Jus Cogens*

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenCommons at University of Connecticut University of Connecticut Masthead Logo OpenCommons@UConn Faculty Articles and Papers School of Law 1988 The aN ture of Jus Cogens Mark Weston Janis University of Connecticut School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_papers Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Janis, Mark Weston, "The aN ture of Jus Cogens" (1988). Faculty Articles and Papers. 410. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_papers/410 +(,121/,1( Citation: Mark W. Janis, Nature of Jus Cogens, 3 Conn. J. Int'l L. 359 (1988) Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Mon May 13 10:06:19 2019 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at https://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information Use QR Code reader to send PDF to your smartphone or tablet device COLLOQUY THE NATURE OF JUS COGENS* by Mark W. Janis** Jus cogens, compelling law, is the modern concept of international law that posits norms so fundamental to the public order of the interna- tional community that they are potent enough to invalidate contrary rules which might otherwise be consensually established by states. The most notable appearance of jus cogens is, of course, in article 53 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties,' where the term is rendered in English as "peremptory norm": A treaty is void if, at the time of its conclusion, it conflicts with a peremptory norm of general international law. -

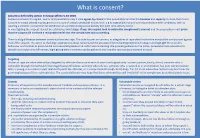

What Is Consent?

What is consent? Consent is defined by section 74 Sexual Offences Act 2003. Someone consents to vaginal, anal or oral penetration only if s/he agrees by choice to that penetration and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice. Consent to sexual activity may be given to one sort of sexual activity but not another, e.g.to vaginal but not anal sex or penetration with conditions, such as wearing a condom. Consent can be withdrawn at any time during sexual activity and each time activity occurs. In investigating the suspect, it must be established what steps, if any, the suspect took to obtain the complainant’s consent and the prosecution must prove that the suspect did not have a reasonable belief that the complainant was consenting. There is a big difference between consensual sex and rape. This aide focuses on consent, as allegations of rape often involve the word of the complainant against that of the suspect. The aim is to challenge assumptions about consent and the associated victim-blaming myths/stereotypes and highlight the suspect’s behaviour and motives to prove he did not reasonably believe the victim was consenting. We provide guidance to the police, prosecutors and advocates to identify and explain the differences, highlighting where evidence can be gathered and how the case can be presented in court. Targeting Victims of rape are often selected and targeted by offenders because of ease of access and opportunity - current partner, family, friend, someone who is vulnerable through mental health/ learning/physical difficulties, someone who sells sex, someone who is isolated or in an institution, has poor communication skills, is young, in a current or past relationship with the offender, or is compromised through drink/drugs. -

Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies

future internet Review Trust, but Verify: Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies Brian Pickering IT Innovation, Electronics and Computing, University of Southampton, University Road, Southampton SO17 1BJ, UK; [email protected] Abstract: To use technology or engage with research or medical treatment typically requires user consent: agreeing to terms of use with technology or services, or providing informed consent for research participation, for clinical trials and medical intervention, or as one legal basis for processing personal data. Introducing AI technologies, where explainability and trustworthiness are focus items for both government guidelines and responsible technologists, imposes additional challenges. Understanding enough of the technology to be able to make an informed decision, or consent, is essential but involves an acceptance of uncertain outcomes. Further, the contribution of AI- enabled technologies not least during the COVID-19 pandemic raises ethical concerns about the governance associated with their development and deployment. Using three typical scenarios— contact tracing, big data analytics and research during public emergencies—this paper explores a trust- based alternative to consent. Unlike existing consent-based mechanisms, this approach sees consent as a typical behavioural response to perceived contextual characteristics. Decisions to engage derive from the assumption that all relevant stakeholders including research participants will negotiate on an ongoing basis. Accepting dynamic negotiation between the main stakeholders as proposed here introduces a specifically socio–psychological perspective into the debate about human responses Citation: Pickering, B. Trust, but to artificial intelligence. This trust-based consent process leads to a set of recommendations for the Verify: Informed Consent, AI ethical use of advanced technologies as well as for the ethical review of applied research projects. -

Medieval Canon Law and Early Modern Treaty Law Lesaffer, R.C.H

Tilburg University Medieval canon law and early modern treaty law Lesaffer, R.C.H. Published in: Journal of the History of International Law Publication date: 2000 Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Lesaffer, R. C. H. (2000). Medieval canon law and early modern treaty law. Journal of the History of International Law, 2(2), 178-198. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. sep. 2021 178 Journal of the History of International Law The Medieval Canon Law of Contract and Early Modern Treaty Law Randall Lesaffer Professor of Legal History, Catholic University of Brabant at Tilburg; Catholic University of Leuven The earliest agreements between political entities which can be considered to be treaties date back from the third millennium B.C1. Throughout history treaties have continuously been a prime instrument of organising relations between autonomous powers. -

Claimant's Reply to Article 1128 Submissions of the United

IN THE ARBITRATION UNDER CHAPTER ELEVEN OF THE NAFTA AND THE ICSID CONVENTION BETWEEN: MOBIL INVESTMENTS CANADA INC. Claimant AND GOVERNMENT OF CANADA Respondent ICSID Case No. ARB/15/6 CLAIMANT’S REPLY TO ARTICLE 1128 SUBMISSIONS OF THE UNITED STATES AND MEXICO ARBITRAL TRIBUNAL: Sir Christopher Greenwood QC Mr. J. William Rowley QC Dr. Gavan Griffith QC SECRETARY OF THE TRIBUNAL: Ms. Lindsay Gastrell 14 December 2017 I. INTRODUCTION 1. In this Reply, Mobil provides the following observations on the Article 1128 Submissions filed by the United States and Mexico in this arbitration:1 • The Article 1128 Submissions confirm that the obligations of the NAFTA must be interpreted and performed in good faith. • The Article 1128 Submissions, to the extent they address hypothetical claims based on “free-standing” obligations under customary international law, are largely irrelevant to addressing the claim before this Tribunal. Mobil’s claim is based on Canada’s breach of obligations found in Article 1106(1), not on “free-standing obligations” that are separate and apart from the NAFTA. • The Article 1128 Submissions’ comments on the scope of consent to arbitration under the NAFTA cannot be understood as precluding the application of customary international law to define the obligations contained in Article 1106(1). Under NAFTA Article 1131(1), this Tribunal is not simply permitted, but actually required to apply customary international law rules—including those concerning good faith and cessation of internationally wrongful conduct—in deciding the dispute before it. 2. As a preface to this Reply, Mobil notes that neither the U.S. Submission nor the Mexico Submission addresses the interpretation of Articles 1116(2) or 1117(2). -

Natural Law in the Modern European Constitutions Gottfried Dietze

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Natural Law Forum 1-1-1956 Natural Law in the Modern European Constitutions Gottfried Dietze Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/nd_naturallaw_forum Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Dietze, Gottfried, "Natural Law in the Modern European Constitutions" (1956). Natural Law Forum. Paper 7. http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/nd_naturallaw_forum/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Natural Law Forum by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATURAL LAW IN THE MODERN EUROPEAN CONSTITUTIONS Gottfried Dietze THE SECOND WORLD WAR has brought about one of the most fundamental revolutions in modem European history. Unlike its predecessors of 1640, 1789, and 1917, the revolution of 1945 was not confined to one country. Its ideas did not gradually find their way into the well-established and stable orders of other societies. It was a spontaneous movement in the greater part of a continent that had traditionally been torn by dissension; and its impact was immediately felt by a society which was in a state of dissolution and despair. The revolution of 1945 had a truly European character. There was no uprising of a lower nobility as in 1640; of a third estate as in the French Revolution; of the proletariat as in Russia. Since fascism had derived support from all social strata and preached the solidarity of all citizens of the nation, there could hardly be room for a class struggle. -

Citizen Science: Framing the Public, Information Exchange, and Communication in Crowdsourced Science

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2014 Citizen Science: Framing the Public, Information Exchange, and Communication in Crowdsourced Science Todd Ernest Suomela University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Communication Commons, and the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Suomela, Todd Ernest, "Citizen Science: Framing the Public, Information Exchange, and Communication in Crowdsourced Science. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2014. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/2864 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Todd Ernest Suomela entitled "Citizen Science: Framing the Public, Information Exchange, and Communication in Crowdsourced Science." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Communication and Information. Suzie Allard, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Carol Tenopir, Mark Littmann, Harry Dahms Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Citizen Science: Framing the Public, Information Exchange, and Communication in Crowdsourced Science ADissertationPresentedforthe Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Todd Ernest Suomela August 2014 c by Todd Ernest Suomela, 2014 All Rights Reserved. -

Personal Autonomy and Informed Consent: Conceptual and Normative Analyses

Personal Autonomy and Informed Consent: Conceptual and Normative Analyses Jesper Ahlin Licentiate thesis in philosophy KTH Royal Institute of Technology Stockholm, «Ï; © «Ï; Ahlin All rights reserved. Ahlin, J. Personal Autonomy and Informed Consent:Conceptual and Normative Analyses Licentiate thesis KTH Royal Institute of Technology TOC ;Ê-Ï-;;-- TOO ÏE«-ÊÊtÏ Typeset by the author, with help from Jesper Jerkert, using LATEX and BTCTEX.Printed by Universitetsservice US-AB, Drottning Kristinas väg tB, ÏÏ Ê Stockholm. I know what I know Acknowledgments I am grateful to Barbro Fröding, Sven Ove Hansson, and Niklas Juth for their su- pervision of this thesis, and to Gert Helgesson for his many useful comments on an earlier dra. Also, I thank William Bülow, Jesper Jerkert,Björn Lundgren, Payam Moula, and Maria Nordström, among others, for support and stimulating discussions. My thanks are extended to the Higher seminar at the Division of Philosophy, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, the Higher seminar at the Centre for Healthcare Ethics, Karolinska Institutet, and the VR/FORTE research program for providing opportu- nities to discuss and develop these ideas. All errors and mistakes are of course my own. his research was supported by the Swedish Research Council (VR) and the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (FORTE), contract no. «Ï– «, for the project Addressing Ethical Obstacles to Person Centred Care. Stockholm,August «Ï; Jesper Ahlin Abstract his licentiate thesis is comprised of a “kappa” and two articles. he kappa includes an account of personal autonomy and informed consent, an explanation of how the concepts and articles relate to each other, and a summary in Swedish. -

The Classification Into Branches of Modern Legal

THE CLASSIFICAT ION IN T O BRANCHES OF MODERN LEGAL SYS T EMS 443 Revista de Derecho de la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso XXVII (Valparaíso, Chile, 2º semestre de 2006) [pp. 443 - 472] THE classiFicatiON INTO BRANCHES OF MODERN LEGAL SYSTEMS AND ROMAN laW TRADITIONS [“La clasificación en ramas de los sistemas legales modernos y las tradiciones del Derecho romano”] GÁBOR HAMZA * RESUMEN ABS T RAC T El presente trabajo se basa en la lec- This paper is based on the author’s ción inaugural del autor para su ingreso opening lesson upon his entry into the en la Academia Húngara de Ciencias; y Hungarian Academy of Sciences. He en él examina las diversas divisiones en hereby discusses the various divisions in partes o ramas de que ha sido objeto el parts or branches of the Law throughout Derecho, a través de la historia, empe- history, beginning with those formulated zando por las formuladas por los juristas by Roman jurists of public and private romanos, de Derecho público y privado y Law, and of civil and praetorian (hono- Derecho civil y pretorio (honorario). Es rary) Law. The first one has undoubte- sobre todo la primera que ha tenido una dly some influence, which the author influencia posterior, que el autor analiza analyzes among the commentators, in entre los glosadores y comentaristas, en la the humanistic judicial practice, and in jurisprudencia humanística y en diversas several later schools, with an extension escuelas de la época posterior, con exten- to Scottish law and to the common law sión al derecho escocés y al common law, and, of course in the juridical science of y desde luego en la Ciencia jurídica de the XIX and XX centuries.