Consultation and Consent Norms Under Ilo Convention No. 169 and the Un Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Compared

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Convention Theory: Is There a French School of Organizational Institutionalism?

CONVENTION THEORY : IS THERE A FRENCH SCHOOL OF ORGANIZATIONAL INSTITUTIONALISM? Thibault Daudigeos, Bertrand Valiorgue To cite this version: Thibault Daudigeos, Bertrand Valiorgue. CONVENTION THEORY : IS THERE A FRENCH SCHOOL OF ORGANIZATIONAL INSTITUTIONALISM?. 2010. hal-00512374 HAL Id: hal-00512374 http://hal.grenoble-em.com/hal-00512374 Preprint submitted on 30 Aug 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. "CONVENTION THEORY": IS THERE A FRENCH SCHOOL OF ORGANIZATIONAL INSTITUTIONALISM? Thibault Daudigeos Grenoble Ecole de Management Chercheur Associé, Institut Français de Gouvernement des Entreprises [email protected] Bertrand Valiorgue ESC Clermont Chercheur Associé, Institut Français de Gouvernement des Entreprises [email protected] We thank the participants of the NIW2010 and AIMS 2010 workshops for their insightful comments. 1 "CONVENTION THEORY": IS THERE A FRENCH SCHOOL OF ORGANIZATIONAL INSTITUTIONALISM? ABSTRACT This paper highlights overlap and differences between Convention Theory and New Organizational Institutionalism and thus states the strong case for profitable dialog. It shows how the former can facilitate new institutional approaches. First, convention theory rounds off the model of institutionalized action by turning the spotlight to the role of evaluation in the coordination effort. -

Jus Cogens As a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr

Penn State International Law Review Volume 29 Article 2 Number 2 Penn State International Law Review 9-1-2010 Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Petsche, Dr. Markus (2010) "Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 29: No. 2, Article 2. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol29/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Articles I Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche* Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .............................................. 235 I. THE INAPPROPRIATENESS OF CHARACTERIZING JUS COGENS AS A RULE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE LIMITED RELEVANCE OF JUS COGENS FOR THE PRACTICE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW...................................238 A. FundamentalConceptual and Theoretical Flaws ofJus Cogens .................................... 238 1. Origins of Jus Cogens. .................. ..... 238 2. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking Substance........ 242 3. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Procedure for Its Determination. ............ ......... .......... 243 4. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Proper Theoretical Basis.......................... 245 B. The Limited Relevance of Jus Cogens for the Law of Treaties: Rare and Unsuccessful Reliance on Jus * DEA (Paris 1); LL.M. (NYU); Ph.D. -

Indigenous and Tribal People's Rights Over Their Ancestral Lands

INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 56/09 30 December 2009 Original: Spanish INDIGENOUS AND TRIBAL PEOPLES’ RIGHTS OVER THEIR ANCESTRAL LANDS AND NATURAL RESOURCES Norms and Jurisprudence of the Inter‐American Human Rights System 2010 Internet: http://www.cidh.org E‐mail: [email protected] OAS Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data Derechos de los pueblos indígenas y tribales sobre sus tierras ancestrales y recursos naturales: Normas y jurisprudencia del sistema interamericano de derechos humanos = Indigenous and tribal people’s rights over their ancestral lands and natural resources: Norms and jurisprudence of the Inter‐American human rights system / [Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights.] p. ; cm. (OEA documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L)(OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978‐0‐8270‐5580‐3 1. Human rights‐‐America. 2. Indigenous peoples‐‐Civil rights‐‐America. 3. Indigenous peoples‐‐Land tenure‐‐America. 4. Indigenous peoples‐‐Legal status, laws, etc.‐‐America. 5. Natural resources‐‐Law and legislation‐‐America. I. Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. II Series. III. Series. OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.56/09 Document published thanks to the financial support of Denmark and Spain Positions herein expressed are those of the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights and do not reflect the views of Denmark or Spain Approved by the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights on December 30, 2009 INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS MEMBERS Luz Patricia Mejía Guerrero Víctor E. Abramovich Felipe González Sir Clare Kamau Roberts Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro Florentín Meléndez Paolo G. Carozza ****** Executive Secretary: Santiago A. -

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don't Have Sex Without Them

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don’t Have Sex Without Them A Lesson Plan from Rights, Respect, Responsibility: A K-12 Curriculum Fostering responsibility by respecting young people’s rights to honest sexuality education. ADVANCE PREPARATION FOR LESSON: NSES ALIGNMENT: • Download the YouTube video on consent, “2 Minutes Will By the end of 12th grade, Change the Way You Think About Consent,” at https://www. students will be able to: youtube.com/watch?v=laMtr-rUEmY. HR.12.CC.3 – Define sexual consent and explain its • Also download the trailer for Pitch Perfect 2 - The Ellen Show implications for sexual decision- version (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBwOYQd21TY), making. queuing it up to play a brief clip between 2:10 and 2:27. PS.12.CC.3 – Explain why using tricks, threats or coercion in • If you cannot download and save these to your desktop in relationships is wrong. advance, talk with your school’s IT person to ensure you have HR.12.INF.2 – Analyze factors, internet access to that link during class. including alcohol and other substances, that can affect the • Print out the skit scenarios and cut out each pair, making sure ability to give or perceive the the correct person 1 goes with the correct person 2. Determine provision of consent to sexual how many pairs there will be in your class and make several activity. copies of each scenario, enough for each pair to get one. TARGET GRADE: Grade 10 LEARNING OBJECTIVES: Lesson 1 By the end of this lesson, students will be able to: 1. -

David Lewis on Convention

David Lewis on Convention Ernie Lepore and Matthew Stone Center for Cognitive Science Rutgers University David Lewis’s landmark Convention starts its exploration of the notion of a convention with a brilliant insight: we need a distinctive social competence to solve coordination problems. Convention, for Lewis, is the canonical form that this social competence takes when it is grounded in agents’ knowledge and experience of one another’s self-consciously flexible behavior. Lewis meant for his theory to describe a wide range of cultural devices we use to act together effectively; but he was particularly concerned in applying this notion to make sense of our knowledge of meaning. In this chapter, we give an overview of Lewis’s theory of convention, and explore its implications for linguistic theory, and especially for problems at the interface of the semantics and pragmatics of natural language. In §1, we discuss Lewis’s understanding of coordination problems, emphasizing how coordination allows for a uniform characterization of practical activity and of signaling in communication. In §2, we introduce Lewis’s account of convention and show how he uses it to make sense of the idea that a linguistic expression can come to be associated with its meaning by a convention. Lewis’s account has come in for a lot of criticism, and we close in §3 by addressing some of the key difficulties in thinking of meaning as conventional in Lewis’s sense. The critical literature on Lewis’s account of convention is much wider than we can fully survey in this chapter, and so we recommend for a discussion of convention as a more general phenomenon Rescorla (2011). -

Guide on Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights

Guide on Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights Freedom of thought, Conscience and religion Updated on 30 April 2021 This Guide has been prepared by the Registry and does not bind the Court. Guide on Article 9 of the Convention – Freedom of thought, conscience and religion Publishers or organisations wishing to translate and/or reproduce all or part of this report in the form of a printed or electronic publication are invited to contact [email protected] for information on the authorisation procedure. If you wish to know which translations of the Case-Law Guides are currently under way, please see Pending translations. This Guide was originally drafted in French. It is updated regularly and, most recently, on 30 April 2021. It may be subject to editorial revision. The Case-Law Guides are available for downloading at www.echr.coe.int (Case-law – Case-law analysis – Case-law guides). For publication updates please follow the Court’s Twitter account at https://twitter.com/ECHR_CEDH. © Council of Europe/European Court of Human Rights, 2021 European Court of Human Rights 2/99 Last update: 30.04.2021 Guide on Article 9 of the Convention – Freedom of thought, conscience and religion Table of contents Note to readers .............................................................................................. 5 Introduction ................................................................................................... 6 I. General principles and applicability ........................................................... 8 A. The importance of Article 9 of the Convention in a democratic society and the locus standi of religious bodies ............................................................................................................ 8 B. Convictions protected under Article 9 ........................................................................................ 8 C. The right to hold a belief and the right to manifest it .............................................................. 11 D. -

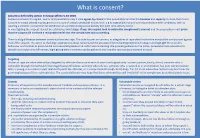

What Is Consent?

What is consent? Consent is defined by section 74 Sexual Offences Act 2003. Someone consents to vaginal, anal or oral penetration only if s/he agrees by choice to that penetration and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice. Consent to sexual activity may be given to one sort of sexual activity but not another, e.g.to vaginal but not anal sex or penetration with conditions, such as wearing a condom. Consent can be withdrawn at any time during sexual activity and each time activity occurs. In investigating the suspect, it must be established what steps, if any, the suspect took to obtain the complainant’s consent and the prosecution must prove that the suspect did not have a reasonable belief that the complainant was consenting. There is a big difference between consensual sex and rape. This aide focuses on consent, as allegations of rape often involve the word of the complainant against that of the suspect. The aim is to challenge assumptions about consent and the associated victim-blaming myths/stereotypes and highlight the suspect’s behaviour and motives to prove he did not reasonably believe the victim was consenting. We provide guidance to the police, prosecutors and advocates to identify and explain the differences, highlighting where evidence can be gathered and how the case can be presented in court. Targeting Victims of rape are often selected and targeted by offenders because of ease of access and opportunity - current partner, family, friend, someone who is vulnerable through mental health/ learning/physical difficulties, someone who sells sex, someone who is isolated or in an institution, has poor communication skills, is young, in a current or past relationship with the offender, or is compromised through drink/drugs. -

Pragmatic Reasoning and Semantic Convention: a Case Study on Gradable Adjectives*

Pragmatic Reasoning and Semantic Convention: A Case Study on Gradable Adjectives* Ming Xiang, Christopher Kennedy, Weijie Xu and Timothy Leffel University of Chicago Abstract Gradable adjectives denote properties that are relativized to contextual thresholds of application: how long an object must be in order to count as long in a context of utterance depends on what the threshold is in that context. But thresholds are variable across contexts and adjectives, and are in general uncertain. This leads to two questions about the meanings of gradable adjectives in particular contexts of utterance: what truth conditions are they understood to introduce, and what information are they taken to communicate? In this paper, we consider two kinds of answers to these questions, one from semantic theory, and one from Bayesian pragmatics, and assess them relative to human judgments about truth and communicated information. Our findings indicate that although the Bayesian accounts accurately model human judgments about what is communicated, they do not capture human judgments about truth conditions unless also supplemented with the threshold conventions postulated by semantic theory. Keywords: Gradable adjectives, Bayesian pragmatics, context dependence, semantic uncer- tainty 1 Introduction 1.1 Gradable adjectives and threshold uncertainty Gradable adjectives are predicative expressions whose semantic content is based on a scalar concept that supports orderings of the objects in their domains. For example, the gradable adjectives long and short order relative to height; heavy and light order relative to weight, and so on. Non-gradable adjectives like digital and next, on the other hand, are not associated with a scalar concept, at least not grammatically. -

Convention on the Rights of the Child

Convention on the Rights of the Child Adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989 entry into force 2 September 1990, in accordance with article 49 Preamble The States Parties to the present Convention, Considering that, in accordance with the principles proclaimed in the Charter of the United Nations, recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world, Bearing in mind that the peoples of the United Nations have, in the Charter, reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights and in the dignity and worth of the human person, and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom, Recognizing that the United Nations has, in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and in the International Covenants on Human Rights, proclaimed and agreed that everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth therein, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status, Recalling that, in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the United Nations has proclaimed that childhood is entitled to special care and assistance, Convinced that the family, as the fundamental group of society and the natural environment for the growth and well-being of all its members and particularly children, should be afforded -

Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies

future internet Review Trust, but Verify: Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies Brian Pickering IT Innovation, Electronics and Computing, University of Southampton, University Road, Southampton SO17 1BJ, UK; [email protected] Abstract: To use technology or engage with research or medical treatment typically requires user consent: agreeing to terms of use with technology or services, or providing informed consent for research participation, for clinical trials and medical intervention, or as one legal basis for processing personal data. Introducing AI technologies, where explainability and trustworthiness are focus items for both government guidelines and responsible technologists, imposes additional challenges. Understanding enough of the technology to be able to make an informed decision, or consent, is essential but involves an acceptance of uncertain outcomes. Further, the contribution of AI- enabled technologies not least during the COVID-19 pandemic raises ethical concerns about the governance associated with their development and deployment. Using three typical scenarios— contact tracing, big data analytics and research during public emergencies—this paper explores a trust- based alternative to consent. Unlike existing consent-based mechanisms, this approach sees consent as a typical behavioural response to perceived contextual characteristics. Decisions to engage derive from the assumption that all relevant stakeholders including research participants will negotiate on an ongoing basis. Accepting dynamic negotiation between the main stakeholders as proposed here introduces a specifically socio–psychological perspective into the debate about human responses Citation: Pickering, B. Trust, but to artificial intelligence. This trust-based consent process leads to a set of recommendations for the Verify: Informed Consent, AI ethical use of advanced technologies as well as for the ethical review of applied research projects. -

United Nations Convention Against Corruption

04-56160_c1-4.qxd 17/08/2004 12:33 Page 1 Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, A 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: +(43) (1) 26060-0, Fax: +(43) (1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION AGAINST CORRUPTION Printed in Austria V.04-56160—August 2004—copies UNITED NATIONS UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION AGAINST CORRUPTION UNITED NATIONS New York, 2004 Foreword Corruption is an insidious plague that has a wide range of corrosive effects on societies. It undermines democracy and the rule of law, leads to violations of human rights, distorts markets, erodes the quality of life and allows organized crime, terrorism and other threats to human security to flourish. This evil phenomenon is found in all countries—big and small, rich and poor—but it is in the developing world that its effects are most destructive. Corruption hurts the poor disproportionately by diverting funds intended for development, undermining a Government’s ability to provide basic services, feeding inequality and injustice and discouraging foreign aid and investment. Corruption is a key element in economic underperformance and a major obsta- cle to poverty alleviation and development. I am therefore very happy that we now have a new instrument to address this scourge at the global level. The adoption of the United Nations Convention against Corruption will send a clear message that the international community is determined to prevent and control corruption. It will warn the corrupt that betrayal of the public trust will no longer be tolerated. And it will reaffirm the importance of core values such as honesty, respect for the rule of law, account- ability and transparency in promoting development and making the world a better place for all. -

International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance Preamble the States Parties to This Conve

International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance Preamble The States Parties to this Convention, Considering the obligation of States under the Charter of the United Nations to promote universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms, Having regard to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Recalling the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the other relevant international instruments in the fields of human rights, humanitarian law and international criminal law, Also recalling the Declaration on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations in its resolution 47/133 of 18 December 1992, Aware of the extreme seriousness of enforced disappearance, which constitutes a crime and, in certain circumstances defined in international law, a crime against humanity, Determined to prevent enforced disappearances and to combat impunity for the crime of enforced disappearance, Considering the right of any person not to be subjected to enforced disappearance, the right of victims to justice and to reparation, Affirming the right of any victim to know the truth about the circumstances of an enforced disappearance and the fate of the disappeared person, and the right to freedom to seek, receive and impart information to this end, Have agreed on the following articles: Part I Article 1 1. No one shall be subjected to enforced disappearance. 2. No exceptional circumstances whatsoever, whether a state of war or a threat of war, internal political instability or any other public emergency, may be invoked as a justification for enforced disappearance.