The Crusades- Modified -Read Document 1, for Further Understanding Read Document 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature

A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Robert A. Taylor RESEARCH IN MEDIEVAL CULTURE Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Medieval Institute Publications is a program of The Medieval Institute, College of Arts and Sciences Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Robert A. Taylor MEDIEVAL INSTITUTE PUBLICATIONS Western Michigan University Kalamazoo Copyright © 2015 by the Board of Trustees of Western Michigan University All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Taylor, Robert A. (Robert Allen), 1937- Bibliographical guide to the study of the troubadours and old Occitan literature / Robert A. Taylor. pages cm Includes index. Summary: "This volume provides offers an annotated listing of over two thousand recent books and articles that treat all categories of Occitan literature from the earli- est enigmatic texts to the works of Jordi de Sant Jordi, an Occitano-Catalan poet who died young in 1424. The works chosen for inclusion are intended to provide a rational introduction to the many thousands of studies that have appeared over the last thirty-five years. The listings provide descriptive comments about each contri- bution, with occasional remarks on striking or controversial content and numerous cross-references to identify complementary studies or differing opinions" -- Pro- vided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-58044-207-7 (Paperback : alk. paper) 1. Provençal literature--Bibliography. 2. Occitan literature--Bibliography. 3. Troubadours--Bibliography. 4. Civilization, Medieval, in literature--Bibliography. -

THE CRUSADES Toward the End of the 11Th Century

THE MIDDLE AGES: THE CRUSADES Toward the end of the 11th century (1000’s A.D), the Catholic Church began to authorize military expeditions, or Crusades, to expel Muslim “infidels” from the Holy Land!!! Crusaders, who wore red crosses on their coats to advertise their status, believed that their service would guarantee the remission of their sins and ensure that they could spend all eternity in Heaven. (They also received more worldly rewards, such as papal protection of their property and forgiveness of some kinds of loan payments.) ‘Papal’ = Relating to The Catholic Pope (Catholic Pope Pictured Left <<<) The Crusades began in 1095, when Pope Urban summoned a Christian army to fight its way to Jerusalem, and continued on and off until the end of the 15th century (1400’s A.D). No one “won” the Crusades; in fact, many thousands of people from both sides lost their lives. They did make ordinary Catholics across Christendom feel like they had a common purpose, and they inspired waves of religious enthusiasm among people who might otherwise have felt alienated from the official Church. They also exposed Crusaders to Islamic literature, science and technology–exposure that would have a lasting effect on European intellectual life. GET THE INFIDELS (Non-Muslims)!!!! >>>> <<<“GET THE MUSLIMS!!!!” Muslims From The Middle East VS, European Christians WHAT WERE THE CRUSADES? By the end of the 11th century, Western Europe had emerged as a significant power in its own right, though it still lagged behind other Mediterranean civilizations, such as that of the Byzantine Empire (formerly the eastern half of the Roman Empire) and the Islamic Empire of the Middle East and North Africa. -

Baylor School Hedges Library

Owens 1 Baylor School Hedges Library World History I -- Medieval History “In European history, the Middle Ages, or Medieval period, lasted from the 5th to the 15th century. It began with the collapse of the Western Roman Empire and merged into the Renaissance and the Age of Discovery. The Middle Ages is the middle period of the three traditional divisions of Western history: Antiquity, Medieval period, and Modern period. The Medieval period is itself subdivided into the Early, the High, and the Late Middle Ages.” Reference Books R 103 B628o The Oxford dictionary of philosophy R 291.02 W927w World religions: from ancient history to the present R 291.03 B786w World religions R 292 R356o The Oxford guide to classical mythology in the arts, 1300-1990s R 305.4 C557c Chronology of women worldwide: people, places & events that shaped women's history R 305.4 L724a A to Z of ancient Greek and Roman women R 305.4 S112w Women's chronology: a history of women's achievements R 305.409 S313w Women and gender in medieval Europe : an encyclopedia R 355.009 R286r The reader's companion to military history R 355.02 B396e Encyclopedia of guerilla warfare R 355.02 K79d Dictionary of wars R 364.1 B218n Great lives from history: Notorious lives R 394.2 B846f Festivals of the world: the illustrated guide to celebrations, customs, events, and holidays R 411 W927w The world's writing systems R 509 A832a Asimov's chronology of science & discovery R 608.03 E89e Eureka! R 609 W927w World of invention. -

Crusades 1 Crusades

Crusades 1 Crusades The Crusades were religious conflicts during the High Middle Ages through the end of the Late Middle Ages, conducted under the sanction of the Latin Catholic Church. Pope Urban II proclaimed the first crusade in 1095 with the stated goal of restoring Christian access to the holy places in and near Jerusalem. There followed a further six major Crusades against Muslim territories in the east and Detail of a miniature of Philip II of France arriving in Holy Land numerous minor ones as part of an intermittent 200-year struggle for control of the Holy Land that ended in failure. After the fall of Acre, the last Christian stronghold in the Holy Land, in 1291, Catholic Europe mounted no further coherent response in the east. Many historians and medieval contemporaries, such as Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, give equal precedence to comparable, Papal-blessed military campaigns against pagans, heretics, and people under the ban of excommunication, undertaken for a variety of religious, economic, and political reasons, such as the Albigensian Crusade, the Aragonese Crusade, the Reconquista, and the Northern Crusades. While some historians see the Crusades as part of a purely defensive war against the expansion of Islam in the near east, many see them as part of long-running conflicts at the frontiers of Europe, including the Arab–Byzantine Wars, the Byzantine–Seljuq Wars, and the loss of Anatolia by the Byzantines after their defeat by the Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. Urban II sought to reunite the Christian church under his leadership by providing Emperor Alexios I with military support. -

Crusades 1 Crusades

Crusades 1 Crusades The Crusades were military campaigns sanctioned by the Latin Roman Catholic Church during the High Middle Ages through to the end of the Late Middle Ages. In 1095 Pope Urban II proclaimed the first crusade, with the stated goal of restoring Christian access to the holy places in and near Jerusalem. Many historians and some of those involved at the time, like Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, give equal precedence to other papal-sanctioned military campaigns undertaken for a variety of religious, economic, and political reasons, such as the Albigensian Crusade, the The Byzantine Empire and the Sultanate of Rûm before the First Crusade Aragonese Crusade, the Reconquista, and the Northern Crusades. Following the first crusade there was an intermittent 200-year struggle for control of the Holy Land, with six more major crusades and numerous minor ones. In 1291, the conflict ended in failure with the fall of the last Christian stronghold in the Holy Land at Acre, after which Roman Catholic Europe mounted no further coherent response in the east. Some historians see the Crusades as part of a purely defensive war against the expansion of Islam in the near east, some see them as part of long-running conflict at the frontiers of Europe and others see them as confident aggressive papal led expansion attempts by Western Christendom. The Byzantines, unable to recover territory lost during the initial Muslim conquests under the expansionist Rashidun and Umayyad caliphs in the Arab–Byzantine Wars and the Byzantine–Seljuq Wars which culminated in the loss of fertile farmlands and vast grazing areas of Anatolia in 1071, after a sound victory by the occupying armies of Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Manzikert. -

Crusades 1 Crusades

Crusades 1 Crusades The Crusades were a series of religious expeditionary wars blessed by the Pope and the Catholic Church, with the main goal of restoring Christian access to the holy places in and near Jerusalem. The Crusades were originally launched in response to a call from the leaders of the Byzantine Empire for help to fight the expansion into Anatolia of Muslim Seljuk Turks who had cut off access to Jerusalem.[1] The crusaders comprised military units of Roman Catholics from all over western Europe, and were not under unified command. The main series of Crusades, primarily against Muslims, occurred between 1095 and 1291. The Battle of Ager Sanguinis, 1337 miniature Historians have given many of the earlier crusades numbers. After some early successes, the later crusades failed and the crusaders were defeated and forced to return home. Several hundred thousand soldiers became Crusaders by taking vows;[2] the Pope granted them plenary indulgence.[3] Their emblem was the cross—"crusade" is derived from the French term for taking up the cross. Many were from France and called themselves "Franks," which became the common term used by Muslims.[4] At the time Christianity had not yet divided into the large number of geographically intermingled branches later formed, the (western) Catholic and (eastern) Byzantine churches being the main groups; the Crusaders simply considered themselves to be "Christian" rather than Muslim. The term "crusade" is also used to describe religiously motivated campaigns conducted between 1100 and 1600 in territories outside the Levant[5] usually against pagans, heretics, and peoples under the ban of excommunication[6] for a mixture of religious, economic, and political reasons.[7] Rivalries among both Christian and Muslim powers led also to alliances between religious factions against their opponents, such as the Christian alliance with the Sultanate of Rûm during the Fifth Crusade. -

Cilician Armenian Mediation in Crusader-Mongol Politics, C.1250-1350

HAYTON OF KORYKOS AND LA FLOR DES ESTOIRES: CILICIAN ARMENIAN MEDIATION IN CRUSADER-MONGOL POLITICS, C.1250-1350 by Roubina Shnorhokian A thesis submitted to the Department of History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (January, 2015) Copyright ©Roubina Shnorhokian, 2015 Abstract Hayton’s La Flor des estoires de la terre d’Orient (1307) is typically viewed by scholars as a propagandistic piece of literature, which focuses on promoting the Ilkhanid Mongols as suitable allies for a western crusade. Written at the court of Pope Clement V in Poitiers in 1307, Hayton, a Cilician Armenian prince and diplomat, was well-versed in the diplomatic exchanges between the papacy and the Ilkhanate. This dissertation will explore his complex interests in Avignon, where he served as a political and cultural intermediary, using historical narrative, geography and military expertise to persuade and inform his Latin audience of the advantages of allying with the Mongols and sending aid to Cilician Armenia. This study will pay close attention to the ways in which his worldview as a Cilician Armenian informed his perceptions. By looking at a variety of sources from Armenian, Latin, Eastern Christian, and Arab traditions, this study will show that his knowledge was drawn extensively from his inter-cultural exchanges within the Mongol Empire and Cilician Armenia’s position as a medieval crossroads. The study of his career reflects the range of contacts of the Eurasian world. ii Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the financial support of SSHRC, the Marjorie McLean Oliver Graduate Scholarship, OGS, and Queen’s University. -

Papal Overlordship and Protectio of the King, C.1000-1300

1 PAPAL OVERLORDSHIP AND PROTECTIO OF THE KING, c.1000-1300 Benedict Wiedemann UCL Submitted for the degree of PhD in History 2017 2 I, Benedict Wiedemann, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Papal Overlordship and Protectio of the King, c.1000-1300 Abstract This thesis focuses on papal overlordship of monarchs in the middle ages. It examines the nature of alliances between popes and kings which have traditionally been called ‘feudal’ or – more recently – ‘protective’. Previous scholarship has assumed that there was a distinction between kingdoms under papal protection and kingdoms under papal overlordship. I argue that protection and feudal overlordship were distinct categories only from the later twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. Before then, papal-royal alliances tended to be ad hoc and did not take on more general forms. At the beginning of the thirteenth century kingdoms started to be called ‘fiefs’ of the papacy. This new type of relationship came from England, when King John surrendered his kingdoms to the papacy in 1213. From then on this ‘feudal’ relationship was applied to the pope’s relationship with the king of Sicily. This new – more codified – feudal relationship seems to have been introduced to the papacy by the English royal court rather than by another source such as learned Italian jurists, as might have been expected. A common assumption about how papal overlordship worked is that it came about because of the active attempts of an over-mighty papacy to advance its power for its own sake. -

For Some Sixty Years, Commencing in 1260, the Mamluk State in Egypt and Syria Was at War with the Ilkhanid Mongols Based in Persia

For some sixty years, commencing in 1260, the Mamluk state in Egypt and Syria was at war with the Ilkhanid Mongols based in Persia. This is the first comprehensive study of the political and military aspects of the early years of the war, the twenty-one-year period commencing with the battle of cAyn Jalut in Palestine in 1260 and ending in 1281 at the battle of Horns in northern Syria. Between these major confrontations, which resulted from Mongol invasions into Syria, the Mamluk-Ilkhanid struggle was continued in the manner of a 'cold war' with both sides involved in border skirmishes, diplomatic maneuvers, psychological warfare, ideological posturing, espionage and other forms of subterfuge. Here, as in the major battles, the Mamluks usually maintained the upper hand, establishing themselves as the major Muslim power at the time. Using primarily contemporary Arabic and Persian sources, Reuven Amitai- Preiss sheds new light on the confrontation, examining the war within the context of Ilkhanid/Mamluk relations with the Byzantine Empire, the Latin West and the crusading states, as well as with other Mongol states. Cambridge Studies in Islamic Civilization Mongols and Mamluks Cambridge Studies in Islamic Civilization Editorial board DAVID MORGAN (general editor) MICHAEL COOK JOSEF VAN ESS BARBARA FLEMMING TARIF KHALIDI METIN KUNT W.F. MADELUNG ROY MOTTAHEDEH BASIM MUSALLAM Titles in the series B.F. MUSALLEM. Sex and society in Islam: birth control before the nineteenth century SURAIYA FAROQHI. Towns and townsmen of Ottoman Anatolia: trade, crafts and food production in an urban setting, 1520-1650 PATRICIA CRONE. Roman, provincial and Islamic law: the origins of the Islamic patronate STEFAN SPERL. -

Triumphus Matris

LES ENLUMINURES LES ENLUMINURES, LTD. Le Louvre des Antiquaires 2 Place du Palais-Royal 2970 North Lake Shore Drive 75001 Paris (France) Chicago, IL 60657 (USA) tel. +33 (0)1 42 60 15 58 • fax. +33 (0)1 40 15 00 25 tel. +773 929 5986 [email protected] fax. +773 528 3976 [email protected] Noted Missal for use in the diocese of Coutances In Latin, decorated manuscript on parchment Northern or Central France (Paris?), c. 1254-1263 i (parchment) + 260 + ii (parchment, i, a small scrap) folios on parchment, modern foliation, top outer corner recto, ff. 1-6 (ff. 5-6 possibly originally flyleaves), are followed by 244 leaves with original foliation in ink, ii-ccxliiii, top, outer corner recto in roman numerals, now beginning with f. ii, and with f. ccxlv originally unnumbered, ff. 251-260 are later leaves, not included in the original foliation (collation, i6 [all single, original structure uncertain, 5 and 6, originally flyleaves] ii12 [-1, originally numbered f. i, with loss of text] iii-xi12 xii11 [-12, following f. 136, with loss of text] xiii-xvi12 xvii10 [through f. 194] xviii-xix12 xx-xxi8 xxii16 xxiii8 [added quire, 7, f. 257, a stub] xxiv2), the quire with the Canon of the Mass, now missing, once followed quire twelve, quires 2-11 are numbered in roman numerals in the lower margin of the verso of the last leaf of each quire, i-x, quires 3-11 are also numbered at the beginning of the quire with a very tiny roman numeral, bottom, outer margin, recto, horizontal catchwords throughout, very bottom, inside margin, some trimmed, -

7. Crusades (Pdf File)

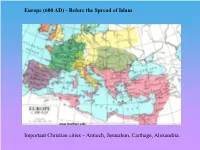

Europe (600 AD) - Before the Spread of Islam www.fordham.edu Important Christian cities – Antioch, Jerusalem, Carthage, Alexandria. The Spread of Islam (632 – 656) www.fordham.edu The Spread of Islam (633 – 656) Saracens Caliph Umar – Daughter married Mohammed. Second Caliphate (633-643). Muslim armies under Umar took control of Egypt, Syria, Palestine, Mesopotamia, North African coast, parts of Persian and Byzantine Empires 637 Jerusalem captured Overthrew 36,000 cities or castles. Destroyed 4,000 churches Built 1400 mosques 643 Omar murdered by Persian slave. The Spread of Islam (750 AD) www.fordham.edu Crusades Peasants Crusade (1096) Peter the Hermit (1050-1115) Made pilgrimage to Holy Land Claimed he saw Christians tortured and killed. Promoted armed pilgrimage 20,000 responded Forced Jews at Regensburg to be baptised. Pillaged on route Wiped out as soon as they entered Asia Minor (Near Nicea in 1096). 1st Crusade (1095-1099) Urban II (1088-1099) Urban made a speech at the Council of Clermont (1095) to French nobles and clergy to take control of Jerusalem. Indulgences offered for those who went on crusade. Pilgrimages were already associated with indulgences. "All who die by the way, whether by land or by sea, or in battle against the pagans, shall have immediate remission of sins. This I grant them through the power of God with which I am invested." The 1st crusade was the only crusade that achieved its goals. Result - Crusaders gained control of Jerusalem in 1099. 1st Crusade (1095-1099) The Princes’ Crusade. First Crusade promoted anti-Semitism. 1096 A German army moved in the opposite direction from Jerusalem and began moving up the Rhine valley gave Jews the option ’convert or die’. -

The Wilted Lily Representations of the Greater Capetian Dynasty Within the Vernacular Tradition of Saint-Denis, 1274-1464

THE WILTED LILY REPRESENTATIONS OF THE GREATER CAPETIAN DYNASTY WITHIN THE VERNACULAR TRADITION OF SAINT-DENIS, 1274-1464 by Derek R. Whaley A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History at the University of Canterbury, 2017. ABSTRACT Much has been written about representations of kingship and regnal au- thority in the French vernacular chronicles popularly known as Les grandes chroniques de France, first composed at the Benedictine abbey of Saint-Denis in 1274 by the monk Primat. However, historians have ignored the fact that Primat intended his work to be a miroir for the princes—a didactic guidebook from which cadets of the Capetian royal family of France could learn good governance and morality. This study intends to correct this oversight by analysing the ways in which the chroniclers Guillaume de Nangis, Richard Lescot, Pierre d’Orgemont, Jean Juvénal des Ursins, and Jean Chartier constructed moral character arcs for many of the members of the Capetian family in their continua- tions to Primat’s text. This thesis is organised into case studies that fol- low the storylines of various cadets from their introduction in the narrative to their departure. Each cadet is analysed in isolation to deter- mine how the continuators portrayed them and what moral themes their depictions supported, if any. Together, these cases prove that the chron- iclers carefully crafted their narratives to serve as miroirs, but also that their overarching goals shifted in response to the growing political cri- ses caused by the Hundred Years War (1337-1453) and the Armagnac- Burgundian civil war (1405-1435).