Folkloric Modernism: Venice's Giardini Della Biennale And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Venice & the Common Ground

COVER Magazine No 02 Venice & the Common Ground Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 01 of 02 EDITORIAL 04 STATEMENTS 25 - 29 EDITORIAL Re: COMMON GROUND Reflections and reactions on the main exhibition By Pedro Gadanho, Steven Holl, Andres Lepik, Beatrice Galilee a.o. VIDEO INTERVIew 06 REPORT 30 - 31 WHAT IS »COMMON GROUND«? THE GOLDEN LIONS David Chipperfield on his curatorial concept Who won what and why Text: Florian Heilmeyer Text: Jessica Bridger PHOTO ESSAY 07 - 21 INTERVIew 32 - 39 EXCAVATING THE COMMON GROUND STIMULATORS AND MODERATORS Our highlights from the two main exhibitions Jury member Kristin Feireiss about this year’s awards Interview: Florian Heilmeyer ESSAY 22 - 24 REVIEW 40 - 41 ARCHITECTURE OBSERVES ITSELF GUERILLA URBANISM David Chipperfield’s Biennale misses social and From ad-hoc to DIY in the US Pavilion political topics – and voices from outside Europe Text: Jessica Bridger Text: Florian Heilmeyer Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 02 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 02 of 02 ReVIEW 42 REVIEW 51 REDUCE REUSE RECYCLE AND NOW THE ENSEMBLE!!! Germany’s Pavilion dwells in re-uses the existing On Melancholy in the Swiss Pavilion Text: Rob Wilson Text: Rob Wilson ESSAY 43 - 46 ReVIEW 52 - 54 OLD BUILDINGS, New LIFE THE WAY OF ENTHUSIASTS On the theme of re-use and renovation across the An exhibition that’s worth the boat ride biennale Text: Elvia Wilk Text: Rob Wilson ReVIEW 47 ESSAY 55 - 60 CULTURE UNDER CONSTRUCTION DARK SIDE CLUB 2012 Mexico’s church pavilion The Dark Side of Debate Text: Rob Wilson Text: Norman Kietzman ESSAY 48 - 50 NEXT 61 ARCHITECTURE, WITH LOVE MANUELLE GAUTRAND Greece and Spain address economic turmoil Text: Jessica Bridger Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 03 EDITORIAL Inside uncube No.2 you’ll find our selections from the 13th Architecture Biennale in Venice. -

Il Linguaggio Della Luce Secondo Vittorio Storaro MAGIC LANTERN Vittorio Storaro’S Language of Light – Paolo Calafiore

NEW BIM LIBRARY AVAILABLE 329 Luce e genius loci Park Associati Light and genius loci: Park Associati La luce nelle città Un'inchiesta Light in the cities: A reportage Vittorio Storaro Una vita per la luce Vittorio Storaro A Life in Light Outdoor LED Lighting Solutions for architecture and urban spaces. Poste ta ane spa – Sped. 1, LO/M n°46) art. 1,comma (conv. 353/2003 – D.L. n L. 27.02.2004 – n A.P. 1828-0560 SSN caribonigroup.com 2019 Anno / year 57 – n.329 2019 trimestrale / quarterly – € 15 Reverberi: innovazione nella SMART CITY TECNOLOGIE ALL’AVANGUARDIA PER CITTÀ INTELLIGENTI LTM: SENSORE LUMINANZA/TRAFFICO e condizioni metereologiche Reverberi Enetec investe nella “Computer vision” e lancia il sensore LTM. Misura della luminanza della strada monitorata, del fl usso di traffi co e delle condizioni meteo debilitanti, in particolare strada bagnata, nebbia, neve. Informazioni che, trasmesse ai sistemi della gamma Reverberi ed Opera, permettono la regolazione in tempo reale ad anello chiuso del fl usso luminoso. I test fi eld hanno dimo- strato potenzialità di risparmio energetico dell’ordine del 30%, ed aggiuntive al 25%-35% conseguibili con dispositivi di regolazione basati su cicli orari. t$POGPSNFBMMB6/*F$&/QBSUFTVJTFOTPSJEJMVNJOBO[B t$SJUFSJ"NCJFOUBMJ.JOJNJ $". EJBDRVJTUPEFMMB1VCCMJDB"NNJOJ TUSB[JPOFEFM <5065,,<967,( Reverberi Enetec srl - [email protected] - Tel 0522-610.611 Fax 0522-810.813 Via Artigianale Croce, 13 - 42035 Castelnovo né Monti - Reggio Emilia www.reverberi.it Everything comes from the project Demí With OptiLight -

Download Artist's CV

ERNESTO NETO 1964 Born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Lives and works in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Education Escola de Artes Visuais Pargua Lage, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Museu de Arte Moderna, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Solo Exhibitions 2021 SunForceOceanLife, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Mentre la vita ci respira, GAMeC, Bergamo, Italy 2020 Water Falls from my Breast to the Sky, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Chicago (permanent commission) 2019 Ernesto Neto: Sopro (Blow), Malba, Museum of Latin American Art, Buenos Aires, Argentine (traveling to Palacio de La Moneda Cultural Center, Santiago, Chile) Ernesto Neto: Children of the Earth, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, Los Angeles Ernesto Neto: Sopro (Blow), curated by Jochen Volz, Pinacoteca, São Paulo, March 30 – July 15; [traveled to Malba, Museum of Latin American Art, Buenos Aires, Argentina; Palacio de La Moneda Cultural Center, Santiago, Chile] 2018 GaiaMotherTree, Beyeler Foundation for the Zurich train station, Basel 2017 Um dia todos fomos peixes, Blue Project Foundation, Barcelona Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel Galeria, São Paulo Water Falls from my Breast to the Sky, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Chicago (permanent installation) 2016 The Serpent’s Energy Gave Birth to Humanity, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York Ernesto Neto, Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma, Helsinki, Finland Enresto Neto: Rui Ni / Voices of the Forest, KUNSTEN Museum of Modern Art Aalborg, Denmark 2015 Ernesto Neto: The Jaguar and the Boa, Kunsthalle Krems, Krems an der Donau, Austria Ernesto Neto and the Huni Kuin ~ -

Venice's Giardini Della Biennale and the Geopolitics of Architecture

FOLKLORIC MODERNISM: VENICE’S GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE AND THE GEOPOLITICS OF ARCHITECTURE Joel Robinson This paper considers the national pavilions of the Venice Biennale, the largest and longest running exposition of contemporary art. It begins with an investigation of the post-fascist landscape of Venice’s Giardini della Biennale, whose built environment continued to evolve in the decades after 1945 with the construction of several new pavilions. With a view to exploring the architectural infrastructure of an event that has always billed itself as ‘international’, the paper asks how the mapping of national pavilions in this context might have changed to reflect the supposedly post-colonial and democratic aspirations of the West after the Second World War. Homing in on the nations that gained representation here in the 1950s and 60s, it looks at three of the more interesting architectural additions to the gardens: the pavilions for Israel, Canada and Brazil. These raise questions about how national pavilions are mobilised ideologically, and form/provide the basis for a broader exploration of the geopolitical superstructure of the Biennale as an institution. Keywords: pavilion, Venice Biennale, modernism, nationalism, geopolitics, postcolonialist. Joel Robinson, The Open University Joel Robinson is a Research Affiliate in the Department of Art History at the Open University and an Associate Lecturer for the Open University in the East of England. His main interests are modern and contemporary art, architecture and landscape studies. He is the author of Life in Ruins: Architectural Culture and the Question of Death in the Twentieth Century (2007), which stemmed from his doctoral work in art history at the University of Essex, and he is co-editor of a new anthology in art history titled Art and Visual Culture: A Reader (2012). -

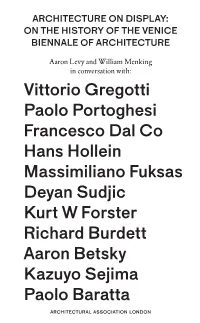

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

C#13 Modern & Contemporary Art Magazine 2013

2013 C#13 Modern & Contemporary Art Magazine C#13 O $PWFSJNBHF"MGSFEP+BBS 7FOF[JB 7FOF[JB EFUBJM Acknowledgements Contributors Project Managers Misha Michael Regina Lazarenko Editors Amy Bower Natasha Cheung Shmoyel Siddiqui Valerie Genty Yvonne Kook Weskott Designers Carrie Engerrand Kali McMillan Shahrzad Ghorban Zoie Yung Illustrator Zoie Yung C# 13 Advisory Board Alexandra Schoolman Cassie Edlefsen Lasch Diane Vivona Emily Labarge John Slyce Michele Robecchi Rachel Farquharson Christie's Education Staff Advisory Board John Slyce Kiri Cragin Thea Philips Freelance C#13 App Developer Pietro Romanelli JJ INDEX I Editor’s Note i British Art 29 Acknowledgements ii Kali McMillan Index iii Index iv Venice C#13 Emerging Artists 58 Robert Mapplethorpe's Au Debut (works form 1970 to 1979) Artist feature on Stephanie Roland at Xavier Hufkens Gallery Artist feature on De Monseignat The Fondation Beyeler Review Artist feature on Ron Muek LITE Art Fair Basel Review Beirut Art Center Review HK Art Basel review Interview with Vito Acconci More than Ink and Brush Interview with Pak Sheun Chuen Selling Out to Big Oil? Steve McQueen's Retrospective at Schaulager, Basel The Frozen Beginnings of Art Contemporary Arts as Alternative Culture Interview with Lee Kit (in traditional Chinese) A Failure to Communicate Are You Alright? Exhibition Review A Failure to Communicate Notes on Oreet Ashrey Keith Haring at Musee D’Art -

Shifting Perspectives in the Venice Biennale's Hungarian Exhibition

17 Looking Forwards or Back? Shifting Perspectives in the Venice Biennale’s Hungarian Exhibition: 1928 and 1948 KINGA BÓDI 268 Kinga Bódi Kinga Bódi, PhD, is curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. As a doctoral fellow at the Swiss Institute for Art Research (SIK–ISEA) she investigated the cultural representation of Hungary at the Venice Biennale from its beginnings until 1948. In her present essay, Bódi jointly discusses the frst contemporary avant-garde Hungarian show in Venice in 1928 and the Biennale edition of 1948, which she interprets as a counterpoint of sorts to the one twenty years earlier, defned by conservative ideological principles and neo-Classicism. Her study examines the historical, social, cultural, political, artistic, professional, and personal background of these two specifc years of Hungarian participation in Venice. At the same time, her essay contributes to current international dialogues on the changing role of international exhibitions, curatorial activities, and (museum) collections. (BH) Looking Forwards or Back? Shifting Perspectives in the Venice Biennale’s Hungarian Exhibition: 1928 and 19481 From 1895 to 1948, it was self-evident that Hungary would take part in the Venice Biennale. During this period, the country too kept in step, more or less, with the artistic and conceptual changes that governed the Biennale, virtually the sole major international exhibition opportunity for Hungarian artists then and now. Tis is perhaps why, for the 124 years since the frst participation, the question of the Hungarian Pavilion has remained at the centre of domestic art-scene debates. Comparing nations has always been a facet of the Venice Biennale. -

1 Artist Portfolio This Document Includes

Artist Portfolio This document includes biographical information of the participating contribu- tors and abstracts of the planned projects (marked bold) for the biennial, com- piled by Asli Serbest and Mona Mahall, following conversations with the contrib- utors. 1 Artist Portfolio Mobile Albania Julia Blawert * 1983 in Offenburg, lives in Leipzig, works in Frankfurt/Main Till Korfhage * 1990 in Frankfurt/Main, lives in Halle, works in Frankfurt/Main Mobile Albania is a nomadic theatrical post state; its territories are temporary and its networks are analogue. Since 2009, it has traveled across Germany and the European continent, with different vehicles through different landscapes: cities, streets, rural areas. Mobile Albania is organized as an open collective with various artists, amateurs, and those that they collide with on the streets and in the cities. While being on the road Mobile Albania constantly develops new methodologies to start a dialogue with the surrounding, as a sort of a street university, as a communal space of artistic practices, knowledge exchange and production. Theater takes place that creates its contents on the street and from the encounter with passersby and residents. In Sinop, Mobile Albania will develop a mobile space where they adopt to the surrounding, interact with people and be tourists, but not regular ones: With the support of a wooden donkey they will find new ways to move around in the city. They will cross borders, fences, walls that normally tell us to stop. It is about bringing the way of wandering around in nature into the city and also to create news ways, to not always accept ready-made paths but to find their own ways. -

1 Eötvös Loránd University Faculty of Humanities Doctoral School of Art

Eötvös Loránd University Faculty of Humanities Doctoral School of Art History Prof. Dr. György Kelényi Professor Emeritus Leader of the Art History Doctoral Program SUMMARY OF DOCTORAL (PhD) DISSERTATION 2014 Kinga Bódi Hungarian Participation at the Venice Art Biennale 1895–1948 Doctoral Supervisors: Dr. Annamária Szőke PhD Prof. Dr. Beat Wyss PhD Appointed Doctoral Reviewers: Dr. Ágnes Prékopa PhD Dr. Ferenc Gosztonyi PhD Members of the Doctoral Committee: Prof. Dr. Katalin Keserü Professor Emeritus, Chair Dr. Julianna Ágoston PhD, Secretary Dr. Julianna P. Szűcs PhD, Member Dr. Anna Eörsi PhD, Replacement Member Dr. Mária Prokopp PhD, Replacement Member 1 Research Background As a student of the Doctoral School of Art History at Eötvös Loránd University Faculty of Humanities, between 2010 and 2013 I had the possibility to participate with my research subject in a three-year international art history research program titled Fokus Projekt «Kunstbetrieb» – Biennale Projekt, sponsored by the Schweizerisches Institut für Kunstwissenschaft in Zurich. The head of the research group was Prof. Dr. Beat Wyss, professor of art history at the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Karlsruhe (HfG). The idea to launch a research project in 2010 based on the unique history of the Venice Biennale, the oldest art biennial of the world and its specially constructed system of international pavilions was in part triggered by the existing monographs on international participation and also by an approach based on Niklas Luhmann’s (1927-1998) culture theory, which regarded the Biennale as one of the most significant “artistic structures” or “art factories” of the world, as well as by the popular exhibition reconstruction research projects of our time. -

Report on Futures Past Editor's Note Table of Contents

Report on the Construction of tranzit j a n 2 2 – a p r 1 3 , 2 0 1 4 a Spaceship Module new museum REPORT ON FUTURES PAST Lauren Cornell fantasies from the socialist side of the Iron tors worked on this exhibition: Vít Havránek, Director of tranzit in Prague, Dóra Curtain. As depictions of the future are always Hegyi, Director of tranzit in Budapest, and Georg Schöllhammer, Director of tranzit deeply tied to the moments in which they are in Vienna. Much like the Museum as Hub program (the New Museum’s interna- conceived, the craft also symbolizes numerous tional partnership through which the exhibition is produced), tranzit organizations realities flattened out and stitched together or actively collaborate with each other, but also work independently to produce art “come back to haunt,”1 as Philip K. Dick has historical research, exhibitions, and new commissions. The work included in this written, all within one seamless vessel. exhibition—all made by artists that tranzit has worked with in some capacity or, alternately, documentation of events or exhibitions tranzit has staged—consti- “Report on the Construction of a Spaceship tutes an “innovative archive”2 of their organization. Module” is an exhibition about art’s movement across time and space. The featured artworks, Across poetry, performative actions, diagrammatic schemas, avatars, found made by artists mainly from former Eastern objects, collections of photographs, and architectural models, “Report on the Bloc countries over the past sixty years, draw Construction of a Spaceship Module” reflects tranzit’s efforts to gather, remember, from a vast breadth of historic periods and and argue for art within Eastern Europe, and its porous connections to art outside artistic movements. -

How the Finnish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale Had to Change Into a Black Box for Contemporary Video Art and How It Became a Symbol for Artists to Defeat

Alvar Aalto Researchers’ Network Seminar – Why Aalto? 9-10 June 2017, Jyväskylä, Finland Against Aalto: How the Finnish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale had to change into a black box for contemporary video art and how it became a symbol for artists to defeat Gianni Talamini architect, PhD Department of Architecture & Civil Engineering City University of Hong Kong Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon, Hong Kong P6424 AC1 Tel: (852) 3442 7618 Email: [email protected] Title Against Aalto: how the Finnish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale had to change into a black box for contemporary video art and how it became a symbol for artists to defeat. Abstract The Finnish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale has hosted more than 30 exhibitions since its construction in 1956. Alvar Aalto designed the space as a temporary structure to display conventional Finnish visual art, such as the work of Helene Schjerfbeck. Although being relatively short, the history of the pavilion has been very eventful. The original plan for a temporary building to be dismantled and rebuilt every second year was not followed. Soon after its construction the pavilion instead went through a period of semi- abandonment, being used as a storage space and green house. Only the death of its designer in 1976 brought interest from the general public back to the pavilion for a short time. In the 1990s the dedicated work of Finnish scholars contributed crucially to the conservation both of the building and its history. After the 2000s Finland again started to use the pavilion as a national exhibition space. -

Past/Future/Present Instroduces a Collaboration Between the Phoenix Art Museum and MAM the Exhibition Will Be on Show Between 01/22 and 04/01 at the São Paulo Museum

Past/Future/Present instroduces a collaboration between the Phoenix Art Museum and MAM The exhibition will be on show between 01/22 and 04/01 at the São Paulo museum The fruit of a collaboration between the Phoenix Art Museum (in Arizona, US) and MAM (Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo), the exhibition Past/Future/Present arrived in the state capital of São Paulo on 01/22 with a selection of 72 works and is the product of the joint efforts of two curators: the North American, Vanessa Davidson, and the Brazilian, Cauê Alves. With pieces produced between 1990 and 2010, the show was first staged in the United States in 2017, displaying Brazilian works of contemporary art to the country’s public, and represented the first exhibition dedicated to MAM’s collection in the US. The exhibition is organized around five themes: The Body/Social Body; Shifting Identities; Landscape, Reimagined; Impossible Objects; and the Reinvention of the Monochrome. The participating artists include: Adriana Varejão, Beatriz Milhazes, Tunga, Dora Longo Bahia, Waltercio Caldas, Carlito Carvalhosa, Leda Catunda, José Damasceno, Rosângela Rennó, Anna Bella Geiger, Carmela Gross and Nelson Leirner. The choice of names represents the varied styles, themes and media present in Brazilian contemporary art, demonstrating that the concept of “Brazilianness” cannot be defined merely in geographic terms. “With this show, we reveal a Brazil to foreigners that they were not familiar with. For the Brazilian public, we want to create the same sense of surprise with contemporary works by renowned artists and also by less well known ones”, states the curator Cauê Alves.