Journal of Visual Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Venice & the Common Ground

COVER Magazine No 02 Venice & the Common Ground Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 01 of 02 EDITORIAL 04 STATEMENTS 25 - 29 EDITORIAL Re: COMMON GROUND Reflections and reactions on the main exhibition By Pedro Gadanho, Steven Holl, Andres Lepik, Beatrice Galilee a.o. VIDEO INTERVIew 06 REPORT 30 - 31 WHAT IS »COMMON GROUND«? THE GOLDEN LIONS David Chipperfield on his curatorial concept Who won what and why Text: Florian Heilmeyer Text: Jessica Bridger PHOTO ESSAY 07 - 21 INTERVIew 32 - 39 EXCAVATING THE COMMON GROUND STIMULATORS AND MODERATORS Our highlights from the two main exhibitions Jury member Kristin Feireiss about this year’s awards Interview: Florian Heilmeyer ESSAY 22 - 24 REVIEW 40 - 41 ARCHITECTURE OBSERVES ITSELF GUERILLA URBANISM David Chipperfield’s Biennale misses social and From ad-hoc to DIY in the US Pavilion political topics – and voices from outside Europe Text: Jessica Bridger Text: Florian Heilmeyer Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 02 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 02 of 02 ReVIEW 42 REVIEW 51 REDUCE REUSE RECYCLE AND NOW THE ENSEMBLE!!! Germany’s Pavilion dwells in re-uses the existing On Melancholy in the Swiss Pavilion Text: Rob Wilson Text: Rob Wilson ESSAY 43 - 46 ReVIEW 52 - 54 OLD BUILDINGS, New LIFE THE WAY OF ENTHUSIASTS On the theme of re-use and renovation across the An exhibition that’s worth the boat ride biennale Text: Elvia Wilk Text: Rob Wilson ReVIEW 47 ESSAY 55 - 60 CULTURE UNDER CONSTRUCTION DARK SIDE CLUB 2012 Mexico’s church pavilion The Dark Side of Debate Text: Rob Wilson Text: Norman Kietzman ESSAY 48 - 50 NEXT 61 ARCHITECTURE, WITH LOVE MANUELLE GAUTRAND Greece and Spain address economic turmoil Text: Jessica Bridger Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 03 EDITORIAL Inside uncube No.2 you’ll find our selections from the 13th Architecture Biennale in Venice. -

Venice's Giardini Della Biennale and the Geopolitics of Architecture

FOLKLORIC MODERNISM: VENICE’S GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE AND THE GEOPOLITICS OF ARCHITECTURE Joel Robinson This paper considers the national pavilions of the Venice Biennale, the largest and longest running exposition of contemporary art. It begins with an investigation of the post-fascist landscape of Venice’s Giardini della Biennale, whose built environment continued to evolve in the decades after 1945 with the construction of several new pavilions. With a view to exploring the architectural infrastructure of an event that has always billed itself as ‘international’, the paper asks how the mapping of national pavilions in this context might have changed to reflect the supposedly post-colonial and democratic aspirations of the West after the Second World War. Homing in on the nations that gained representation here in the 1950s and 60s, it looks at three of the more interesting architectural additions to the gardens: the pavilions for Israel, Canada and Brazil. These raise questions about how national pavilions are mobilised ideologically, and form/provide the basis for a broader exploration of the geopolitical superstructure of the Biennale as an institution. Keywords: pavilion, Venice Biennale, modernism, nationalism, geopolitics, postcolonialist. Joel Robinson, The Open University Joel Robinson is a Research Affiliate in the Department of Art History at the Open University and an Associate Lecturer for the Open University in the East of England. His main interests are modern and contemporary art, architecture and landscape studies. He is the author of Life in Ruins: Architectural Culture and the Question of Death in the Twentieth Century (2007), which stemmed from his doctoral work in art history at the University of Essex, and he is co-editor of a new anthology in art history titled Art and Visual Culture: A Reader (2012). -

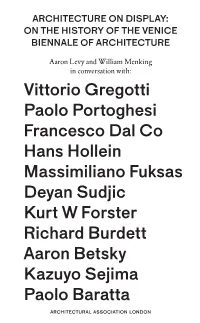

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

Shifting Perspectives in the Venice Biennale's Hungarian Exhibition

17 Looking Forwards or Back? Shifting Perspectives in the Venice Biennale’s Hungarian Exhibition: 1928 and 1948 KINGA BÓDI 268 Kinga Bódi Kinga Bódi, PhD, is curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. As a doctoral fellow at the Swiss Institute for Art Research (SIK–ISEA) she investigated the cultural representation of Hungary at the Venice Biennale from its beginnings until 1948. In her present essay, Bódi jointly discusses the frst contemporary avant-garde Hungarian show in Venice in 1928 and the Biennale edition of 1948, which she interprets as a counterpoint of sorts to the one twenty years earlier, defned by conservative ideological principles and neo-Classicism. Her study examines the historical, social, cultural, political, artistic, professional, and personal background of these two specifc years of Hungarian participation in Venice. At the same time, her essay contributes to current international dialogues on the changing role of international exhibitions, curatorial activities, and (museum) collections. (BH) Looking Forwards or Back? Shifting Perspectives in the Venice Biennale’s Hungarian Exhibition: 1928 and 19481 From 1895 to 1948, it was self-evident that Hungary would take part in the Venice Biennale. During this period, the country too kept in step, more or less, with the artistic and conceptual changes that governed the Biennale, virtually the sole major international exhibition opportunity for Hungarian artists then and now. Tis is perhaps why, for the 124 years since the frst participation, the question of the Hungarian Pavilion has remained at the centre of domestic art-scene debates. Comparing nations has always been a facet of the Venice Biennale. -

1 Artist Portfolio This Document Includes

Artist Portfolio This document includes biographical information of the participating contribu- tors and abstracts of the planned projects (marked bold) for the biennial, com- piled by Asli Serbest and Mona Mahall, following conversations with the contrib- utors. 1 Artist Portfolio Mobile Albania Julia Blawert * 1983 in Offenburg, lives in Leipzig, works in Frankfurt/Main Till Korfhage * 1990 in Frankfurt/Main, lives in Halle, works in Frankfurt/Main Mobile Albania is a nomadic theatrical post state; its territories are temporary and its networks are analogue. Since 2009, it has traveled across Germany and the European continent, with different vehicles through different landscapes: cities, streets, rural areas. Mobile Albania is organized as an open collective with various artists, amateurs, and those that they collide with on the streets and in the cities. While being on the road Mobile Albania constantly develops new methodologies to start a dialogue with the surrounding, as a sort of a street university, as a communal space of artistic practices, knowledge exchange and production. Theater takes place that creates its contents on the street and from the encounter with passersby and residents. In Sinop, Mobile Albania will develop a mobile space where they adopt to the surrounding, interact with people and be tourists, but not regular ones: With the support of a wooden donkey they will find new ways to move around in the city. They will cross borders, fences, walls that normally tell us to stop. It is about bringing the way of wandering around in nature into the city and also to create news ways, to not always accept ready-made paths but to find their own ways. -

Four Artists for the German Pavilion First Information About the German Contribution to the 55Th Venice Biennale 2013 Dear Ladie

Four artists for the German Pavilion First information about the German contribution to the 55th Venice Biennale 2013 Dear Ladies and Gentlemen, In May we announced that Dr. Susanne Gaensheimer, Director of the MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main, has been appointed curator of the German Pavilion at the 55th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia in 2013 for a second time consecutively. Today we would like to present Susanne Gaensheimerʼs curatorial point of departure and the invited artists for 2013. With her plans for the German contribution to the upcoming Venice Biennale, Gaensheimer continues the transnational approach, which characterized her cooperation with Christoph Schlingensief in 2010–2011. “My decision to invite Christoph Schlingensief to Venice was ultimately also influenced by his Africa project, namely the opera village in Ouagadougou”, Susanne Gaensheimer commented in a press release in June 2010. “What becomes clear here is that Schlingensief is not only representative of art in Germany, but that he puts his concerns in a global context. Planning the opera house in Africa and cooperating with the local partners there and, importantly, by using the project for self-reflection in his play Via Intolleranza II, Schlingensief succeeds in giving his analysis of ʻbeing Germanʼ and the issues associated there with a transnational dimension: ‚Why are we always so interested in helping the African continent if we canʼt even help ourselves?ʼ he asked.” Using diverse forms of expression to explore the issues of his generation with uncompromising directness for over 30 years, Christoph Schlingensief pushed the boundaries of art. -

Love Me, Love Me Not Contemporary Art from Azerbaijan and Its Neighbours Collateral Event for the 55Th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale Di Venezia

Love Me, Love Me Not Contemporary Art from Azerbaijan and its Neighbours Collateral Event for the 55th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia Moshiri and Slavs and Tatars, amongst selected artists. Faig Ahmed, Untitled, 2012. Thread Installation, dimensions variable Love Me, Love Me Not is an unprecedented exhibition of contemporary art from Azerbaijan and its neighbours, featuring recent work by 17 artists from Azerbaijan, Iran, Turkey, Russia, and Georgia. Produced and supported by YARAT, a not-for-profit contemporary art organisation based in Baku, and curated by Dina Nasser-Khadivi, the exhibition will be open to the public from 1st June until 24 th November 2013 at Tesa 100, Arsenale Nord, at The 55th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia. Artists featured: Ali Hasanov (Azerbaijan) Faig Ahmed (Azerbaijan) Orkhan Huseynov (Azerbaijan) Rashad Alakbarov (Azerbaijan) Sitara Ibrahimova (Azerbaijan) Afruz Amighi (Iran) Aida Mahmudova (Azerbaijan) Taus Makhacheva (Russia) Shoja Azari (Iran) Farhad Moshiri (Iran) Rashad Babayev (Azerbaijan) Farid Rasulov (Azerbaijan) Mahmoud Bakhshi (Iran) Slavs and Tatars (‘Eurasia’) Ali Banisadr (Iran) Iliko Zautashvili (Georgia) "Each piece in this exhibition has a role of giving the viewers at least one new perspective on the nations represented in this pavilion, with the mere intent to give a better understanding of the area that is being covered. Showcasing work by these artists in a single exhibition aims to, ultimately, question how we each perceive history and geography. Art enables dialogue and the Venice Biennale has proven to be the best arena for cultural exchange." explains curator Dina Nasser-Khadivi. The exhibition offers a diverse range of media and subject matter, with video, installation and painting all on show. -

Contemporary

edited by contemporary art “With its rich roster of art historians, critics, and curators, Contemporary Art: to the Alexander Dumbadze and Suzanne Hudson The contemporary art world has expanded Present provides the essential chart of this exponentially over the last two decades, new field.” generating uncertainty as to what matters Hal Foster, Princeton University and why. Contemporary Art: to the Present offers an unparalleled resource for students, “Featuring a diverse and exciting line-up artists, scholars, and art enthusiasts. It is the of international critics, curators, and art first collection of its kind to bring together historians, Contemporary Art: to the fresh perspectives from leading international Present is an indispensable introduction art historians, critics, curators, and artists for a to the major issues shaping the study of far-ranging dialogue about contemporary art. contemporary art.” con Pamela Lee, Stanford University The book is divided into fourteen thematic clusters: The Contemporary and Globalization; “In Contemporary Art: to the Present, a Art after Modernism and Postmodernism; new generation of critics and scholars comes Formalism; Medium Specificity; Art and of age. Full of fresh ideas, engaged writing, Technology; Biennials; Participation; Activism; and provocative proposals about the art of Agency; The Rise of Fundamentalism; Judgment; the current moment and the immediate past, Markets; Art Schools and the Academy; and this book is sure to become the standard, tem Scholarship. Every section presents three ‘go to’ text in the field of contemporary essays, each of which puts forward a distinct art history.” viewpoint that can be read independently Richard Meyer, author of or considered in tandem. -

Exhibition Reviews

Jcs 3 (1) pp. 117–150 Intellect Limited 2014 Journal of curatorial studies Volume 3 Number 1 © 2014 Intellect Ltd Exhibition Reviews. English language. doi: 10.1386/jcs.3.1.117_7 Exhibition REviEws GLAM! THE PERFORMANCE OF STYLE Curated by Darren Pih, exhibited at Tate Liverpool, 8 February–12 May 2013, Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 14 June–22 September 2013, and Lentos Kunstmuseum Linz, 19 October 2013–2 February 2014. Reviewed by Kathryn Franklin, York University Two exhibitions have opened in 2013 that centre on a specific artistic style of the early 1970s known as glam. Glam! The Performance of Style calls itself the first exhibition to explore glam style and sensibility in depth. The exhibit deals primarily with musicians such as David Bowie, Marc Bolan of T-Rex, and Roxy Music, and artists such as Andy Warhol, Cindy Sherman and David Hockney, along with their roles in shaping and developing the glam aesthetic. Meanwhile, London’s Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) has been granted access to David Bowie’s archive to curate what is argu- ably the most widely discussed exhibit of the year. David Bowie Is focuses on the recording artist’s long and influential career – Bowie himself having just released his twenty-fourth studio album, The Next Day, earlier in the year. Glam rock, however, has never historically counted as a significant phenomenon in discourses on rock music culture. Philip Auslander (2006) suggests that this historical neglect of glam rock is symptomatic of the failure of most major British glam artists to penetrate the American market – with the exception of the ubiquitous David Bowie. -

CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale Di Venezia Presents

LE MUSE INQUIETE WHEN LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA MEETS HISTORY CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale di Venezia presents The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History in collaboration with Istituto Luce-Cinecittà e Rai Teche and with AAMOD-Fondazione Archivio Audiovisivo del Movimento Operaio e Democratico Archivio Centrale dello Stato Archivio Ugo Mulas Bianconero Archivio Cameraphoto Epoche Fondazione Modena Arti Visive Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea IVESER Istituto Veneziano per la Storia della Resistenza e della Società Contemporanea LIMA Amsterdam Peggy Guggenheim Collection Tate Modern La Biennale di Venezia President Roberto Cicutto Board Luigi Brugnaro Vicepresidente Claudia Ferrazzi Luca Zaia Auditors’ Committee Jair Lorenco Presidente Stefania Bortoletti Anna Maria Como Director General Andrea Del Mercato THE DISQUIETED MUSES… The title of the exhibition The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History does not just convey the content that visitors to the Central Pavilion in the Giardini della Biennale will encounter, but also a vision. Disquiet serves as a driving force behind research, which requires dialogue to verify its theories and needs history to absorb knowledge. This is what La Biennale does and will continue to do as it seeks to reinforce a methodology that creates even stronger bonds between its own disciplines. There are six Muses at the Biennale: Art, Architecture, Cinema, Theatre, Music and Dance, given a voice through the great events that fill Venice and the world every year. There are the places that serve as venues for all of La Biennale’s activities: the Giardini, the Arsenale, the Palazzo del Cinema and other cinemas on the Lido, the theatres, the city of Venice itself. -

ITALIAN MODERN ART | ISSUE 3: ISSN 2640-8511 Introduction

ITALIAN MODERN ART | ISSUE 3: ISSN 2640-8511 Introduction ITALIAN MODERN ART - ISSUE 3 | INTRODUCTION italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/introduction-3 Raffaele Bedarida | Silvia Bignami | Davide Colombo Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth-Century Italian Art” (1949), Issue 3, January 2020 https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/methodologies-of- exchange-momas-twentieth-century-italian-art-1949/ ABSTRACT A brief overview of the third issue of Italian Modern Art dedicated to the MoMA 1949 exhibition Twentieth-Century Italian Art, including a literature review, methodological framework, and acknowledgments. If the study of artistic exchange across national boundaries has grown exponentially over the past decade as art historians have interrogated historical patterns, cultural dynamics, and the historical consequences of globalization, within such study the exchange between Italy and the United States in the twentieth-century has emerged as an exemplary case.1 A major reason for this is the history of significant migration from the former to the latter, contributing to the establishment of transatlantic networks and avenues for cultural exchange. Waves of migration due to economic necessity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries gave way to the smaller in size but culturally impactful arrival in the U.S. of exiled Jews and political dissidents who left Fascist Italy during Benito Mussolini’s regime. In reverse, the presence in Italy of Americans – often participants in the Grand Tour or, in the 1950s, the so-called “Roman Holiday” phenomenon – helped to making Italian art, past and present, an important component in the formation of American artists and intellectuals.2 This history of exchange between Italy and the U.S. -

KHALED HAFEZ B. 1963, Lives and Works in Cairo, Egypt BIOGRAPHY Khaled Hafez's Work Delves Into the Dialectics of Collective M

KHALED HAFEZ b. 1963, Lives and works in Cairo, Egypt BIOGRAPHY Khaled Hafez’s work delves into the dialectics of collective memory and consumer culture. Through various media – painting, video, photography and installation – Hafez deconstructs the binary narratives propagated by mass media and disrupts representational dichotomies such as East/West, good/evil. Re-assembling appropriated pop, historical, and political imagery, the artist traces links between the icons and serial format of Pharaonic painting and modern comics. His practice produces an amalgam of visual alphabets that bridge Orient and Occident, and address how globalization and consumerism have altered Middle Eastern societies, to create aesthetic hybrids far beyond the stereotypes of the news. The video installation Mirror Sonata in Six Animated Movements (2015) for the 56th Venice Biennale was the culmination of Hafez’s excavation of Egyptian identity, combining hieroglyphic forms with superhero figures and emblems of warfare. His work has been exhibited at, among others: Venice Biennale (57th, 56th and 55th editions); 12th Cairo Biennale (2010); Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris; British Museum, London; Hiroshima Museum of Contemporary Art, Japan; New Museum, NYC; Saatchi Gallery, London; MuHKA Museum of Art, Antwerp, Belgium; and Kunstmuseum Bonn, Germany. Hafez has been Fulbright Fellow (2005) and Rockefeller Fellow (2009). SELECTED EXHIBITIONS 2017 UTOCORPIS: Les Corps Utopiques, Institut Francais de Casablanca - Morocco VİDEOİST: Unfold, Arte Sanat Galerisi, Ankara