ITALIAN MODERN ART | ISSUE 3: ISSN 2640-8511 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pages 4 Rotella, Lot 51 Pagine

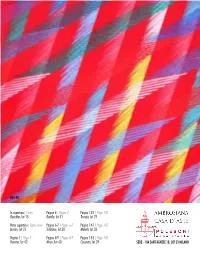

LOT 42 In copertina | Cover Pagine 4 | Pages 4 Pagina 133 | Page 133 Baechler, lot 15 Rotella, lot 51 Turcato, lot 29 Retro copertina | Back cover Pagine 6-7 | Pages 6-7 Pagina 142 | Page 142 Arman, lot 25 Schifano, lot 30 Melotti, lot 33 Pagina 1 | Page 1 Pagine 8-9 | Pages 8-9 Pagina 143 | Page 143 Dorazio, lot 42 Music, lot 60 Cassinari, lot 39 SEDE - VIA SANT’AGNESE 18, 20123 MILANO ASTA ARTE MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA 10 NOVEMBRE 2020 MILANO, VIA SACCHI 7 – presso LA POSTERIA 23 OTTOBRE - 4 NOVEMBRE, MILANO VIA SANT’AGNESE 18 0 (ORARIO 10.00-19.00 – ESCLUSO FESTIVI E 29 OTTOBRE) PREVIO APPUNTAMENTO 7-8-9 NOVEMBRE, MILANO, VIA SACCHI 7 (ORARIO 10.00-19.00) UNICA SESSIONE MARTEDÌ 10 NOVEMBRE 2020 ORE 16.00 LOTTI 1 - 243 PRESENTAZIONE TELEVISIVA TOP LOTS Lunedì 2/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Martedì 3/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Giovedì 5/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Venerdì 6/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre OFFERTE SCRITTE FINO A LUNEDÌ 9 NOVEMBRE 2020 ORE 15.00 FAX +39 02 40703717 [email protected] È possibile partecipare in diretta on-line inscrivendosi (almeno 24 ore prima) sul nostro sito www.ambrosianacasadaste.com CONSULTAZIONE CATALOGO E MODULISTICA www.ambrosianacasadaste.com da venerdì 23 ottobre 2020 AMBROSIANA CASA D’ASTE / GALLERIA POLESCHI CASA D’ASTE - VIA SANT’AGNESE 18 20123 MILANO - TEL. +39 0289459708 - FAX +39 0240703717 www.ambrosianacasadaste.com • [email protected] LOT 51 338 1226703 5 MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY ART -

Copertina Artepd.Cdr

Trent’anni di chiavi di lettura Siamo arrivati ai trent’anni, quindi siamo in quell’età in cui ci sentiamo maturi senza esserlo del tutto e abbiamo tantissime energie da spendere per il futuro. Sono energie positive, che vengono dal sostegno e dal riconoscimento che il cammino fin qui percorso per far crescere ArtePadova da quella piccola edizio- ne inaugurale del 1990, ci sta portando nella giusta direzione. Siamo qui a rap- presentare in campo nazionale, al meglio per le nostre forze, un settore difficile per il quale non è ammessa l’improvvisazione, ma serve la politica dei piccoli passi; siamo qui a dimostrare con i dati di questa edizione del 2019, che siamo stati seguiti con apprezzamento da un numero crescente di galleristi, di artisti, di appassionati cultori dell’arte. E possiamo anche dire, con un po’ di vanto, che negli anni abbiamo dato il nostro contributo di conoscenza per diffondere tra giovani e meno giovani l’amore per l’arte moderna: a volte snobbata, a volte non compresa, ma sempre motivo di dibattito e di curiosità. Un tentativo questo che da qualche tempo stiamo incentivando con l’apertura ai giovani artisti pro- ponendo anche un’arte accessibile a tutte le tasche: tanto che nei nostri spazi figurano, democraticamente fianco a fianco, opere da decine di migliaia di euro di valore ed altre che si fermano a poche centinaia di euro. Se abbiamo attraversato indenni il confine tra due secoli con le sue crisi, è per- ché l’arte è sì bene rifugio, ma sostanzialmente rappresenta il bello, dimostra che l’uomo è capace di grandi azzardi e di mettersi sempre in gioco sperimen- tando forme nuove di espressione; l’arte è tecnica e insieme fantasia, ovvero un connubio unico e per questo quasi magico tra terra e cielo. -

Cézanne and the Modern: Masterpieces of European Art from the Pearlman Collection

Cézanne and the Modern: Masterpieces of European Art from the Pearlman Collection Paul Cézanne Mont Sainte-Victoire, c. 1904–06 (La Montagne Sainte-Victoire) oil on canvas Collection of the Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation, on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum TEACHER’S STUDY GUIDE WINTER 2015 Contents Program Information and Goals .................................................................................................................. 3 Background to the Exhibition Cézanne and the Modern ........................................................................... 4 Preparing Your Students: Nudes in Art ....................................................................................................... 5 Artists’ Background ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Modern European Art Movements .............................................................................................................. 8 Pre- and Post-Visit Activities 1. About the Artists ....................................................................................................................... 9 Artist Information Sheet ........................................................................................................ 10 Modern European Art Movements Fact Sheet .................................................................... 12 Student Worksheet ............................................................................................................... -

DISENCHANTING the AMERICAN DREAM the Interplay of Spatial and Social Mobility Through Narrative Dynamic in Fitzgerald, Steinbeck and Wolfe

DISENCHANTING THE AMERICAN DREAM The Interplay of Spatial and Social Mobility through Narrative Dynamic in Fitzgerald, Steinbeck and Wolfe Cleo Beth Theron Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr. Dawid de Villiers March 2013 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za ii DECLARATION By submitting this thesis/dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2013 Copyright © Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za iii ABSTRACT This thesis focuses on the long-established interrelation between spatial and social mobility in the American context, the result of the westward movement across the frontier that was seen as being attended by the promise of improving one’s social standing – the essence of the American Dream. The focal texts are F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925), John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (1939) and Thomas Wolfe’s You Can’t Go Home Again (1940), journey narratives that all present geographical relocation as necessary for social progression. In discussing the novels’ depictions of the itinerant characters’ attempts at attaining the American Dream, my study draws on Peter Brooks’s theory of narrative dynamic, a theory which contends that the plotting operation is a dynamic one that propels the narrative forward toward resolution, eliciting meanings through temporal progression. -

Whole Document

Copyright By Christin Essin Yannacci 2006 The Dissertation Committee for Christin Essin Yannacci certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Landscapes of American Modernity: A Cultural History of Theatrical Design, 1912-1951 Committee: _______________________________ Charlotte Canning, Supervisor _______________________________ Jill Dolan _______________________________ Stacy Wolf _______________________________ Linda Henderson _______________________________ Arnold Aronson Landscapes of American Modernity: A Cultural History of Theatrical Design, 1912-1951 by Christin Essin Yannacci, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2006 Acknowledgements There are many individuals to whom I am grateful for navigating me through the processes of this dissertation, from the start of my graduate course work to the various stages of research, writing, and editing. First, I would like to acknowledge the support of my committee members. I appreciate Dr. Arnold Aronson’s advice on conference papers exploring my early research; his theoretically engaged scholarship on scenography also provided inspiration for this project. Dr. Linda Henderson took an early interest in my research, helping me uncover the interdisciplinary connections between theatre and art history. Dr. Jill Dolan and Dr. Stacy Wolf provided exceptional mentorship throughout my course work, stimulating my interest in the theoretical and historical complexities of performance scholarship; I have also appreciated their insights and generous feedback on beginning research drafts. Finally, I have been most fortunate to work with my supervisor Dr. Charlotte Canning. From seminar papers to the final drafts of this project, her patience, humor, honesty, and overall excellence as an editor has pushed me to explore the cultural implications of my research and produce better scholarship. -

Julio Gonzalez Introduction by Andrew Carnduff Ritchie, with Statements by the Artist

Julio Gonzalez Introduction by Andrew Carnduff Ritchie, with statements by the artist. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, in collaboration with the Minneapolis Institute of Art Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1956 Publisher Minneapolis Institute of Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3333 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art JULIO GONZALEZ JULIO GONZALEZ introduction by Andrew Carnduff Ritchie with statements by the artist The Museum of Modern Art New York in collaboration with The Minneapolis Institute of Art TRUSTEES OF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART John Hay W hitney, Chairman of theBoard;//enry A//en Aloe, 1st Vice-Chairman; Philip L. Goodwin, 2nd Vice-Chairman; William A. M. Burden, President; Mrs. David M. Levy, 1st Vice-President; Alfred IL Barr, Jr., Mrs. Bobert Woods Bliss, Stephen C. (dark, Balph F. Colin, Mrs. W. Murray Crane,* Bene ddfarnon court, Mrs. Edsel B. Ford, A. Conger Goodyear, Mrs. Simon Guggenheim,* Wallace K. Harrison, James W. Husted,* Mrs. Albert D. Lasker, Mrs. Henry B. Luce, Ranald II. Macdonald, Mrs. Samuel A. Marx, Mrs. G. Macculloch Miller, William S. Paley, Mrs. Bliss Parkinson, Mrs. Charles S. Payson, Duncan Phillips,* Andrew CarndujJ Bitchie, David Bockefeller, Mrs. John D. Bockefeller, 3rd, Nelson A. Bockefeller, Beardsley Buml, Paul J. Sachs,* John L. Senior, Jr., James Thrall Soby, Edward M. M. Warburg, Monroe Wheeler * Honorary Trustee for Life TRUSTEES OF THE MINNEAPOLIS INSTITUTE OF ARTS Putnam D. -

Sarfatti and Venturi, Two Italian Art Critics in the Threads of Modern Argentinian Art

MODERNIDADE LATINA Os Italianos e os Centros do Modernismo Latino-americano Sarfatti and Venturi, Two Italian Art Critics in the Threads of Modern Argentinian Art Cristina Rossi Introduction Margherita Sarfatti and Lionello Venturi were two Italian critics who had an important role in the Argentinian art context by mid-20th Century. Venturi was only two years younger than Sarfatti and both died in 1961. In Italy, both of them promoted groups of modern artists, even though their aesthetic poetics were divergent, such as their opinions towards the official Mussolini´s politics. Our job will seek to redraw their action within the tension of the artistic field regarding the notion proposed by Pierre Bourdieu, i.e., taking into consider- ation the complex structure as a system of relations in a permanent state of dispute1. However, this paper will not review the performance of Sarfatti and Venturi towards the cultural policies in Italy, but its proposal is to reintegrate their figures – and their aesthetical and political positions – within the interplay of forces in the Argentinian rich cultural fabric, bearing in mind the strategies that were implemented by the local agents with those who they interacted with. Sarfatti and Venturi in Mussolini´s political environment Born into a Jewish Venetian family in 1883, Margherita Grassini got married to the lawyer Cesare Sarfatti and in 1909 moved to Milan, where she started her career as an art critic. Convinced that Milan could achieve a central role in the Italian culture – together with the Jewish gallerist Lino Pesaro – in 1922 Sarfatti promoted the group Novecento. -

The Reason Given for the UK's Decision to Float Sterling Was the Weight of International Short-Term Capital

- Issue No. 181 No. 190, July 6, 1972 The Pound Afloat: The reason given for the U.K.'s decision to float sterling was the weight of international short-term capital movements which, despite concerted intervention from the Bank of England and European central banks, had necessitated massive sup port operations. The U.K. is anxious that the rate should quickly o.s move to a "realistic" level, at or around the old parity of %2. 40 - r,/, .• representing an effective 8% devaluation against the dollar. A w formal devaluation coupled with a wage freeze was urged by the :,I' Bank of England, but this would be politically embarrassing in the }t!IJ light of the U.K. Chancellor's repeated statements that the pound was "not at an unrealistic rate." The decision to float has been taken in spite of a danger that this may provoke an international or European monetary crisis. European markets tend to consider sterling as the dollar's first line of defense and, although the U.S. Treasury reaffirmed the Smithsonian Agreement, there are fears throughout Europe that pressure on the U.S. currency could disrupt the exchange rate re lationship established last December. On the Continent, the Dutch and Belgians have put forward a scheme for a joint float of Common Market currencies against the dollar. It will not easily be implemented, since speculation in the ex change markets has pushed the various EEC countries in different directions. The Germans have been under pressure to revalue, the Italians to devalue. Total opposition to a Community float is ex pected from France (this would sever the ties between the franc and gold), and the French also are adamant that Britain should re affirm its allegiance to the European monetary agreement and return to a fixed parity. -

Modigliani's Recipe: Sex, Drugs and Long, Long Necks

The New York Times, August 3, 2003 Modigliani's Recipe: Sex, Drugs and Long, Long Necks By PETER PLAGENS VINCENT VAN GOGH had a 10-year working life that can hardly be called a "career," and yet he's just about the biggest draw ever in museum exhibitions, at least per square inch of canvas covered. When the 1998 "Van Gogh's van Goghs" exhibition entered the home stretch of its run at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, officials had to keep the place open 24 hours a day on the last weekend to accommodate the crowds. Amedeo Modigliani O.K., that's van Gogh. But since June 26, visitors have been streaming into the same museum at the rate of more than 1,400 a day (which a spokesperson calls "astounding" for them) to see the work of a different painter with an equally brief working life. The attraction, which originated at the Albright-Knox Gallery in Buffalo (where the museum had to turn away visitors during the last two weeks) and then stopped at the Kimbell Museum in Fort Worth, is an exhibition called "Modigliani and the Artists of Montparnasse." (It runs through Sept. 28.) Although the show includes healthy doses of Chagall, Soutine and Rivera (among others), the benighted Amedeo Modigliani (1884- 1920) is the real draw. What is it about this artist, who painted deceptively simple, semi-abstracted, sloe-eyed women over and over again, that pleases the public so much? It could be at least partly the biography. Modigliani was born an outsider — his parents were Sephardic Jews in Livorno, Italy — and grew up sickly and tubercular. -

Casa Jorn, Sintesi Immaginista Delle Arti Casa Jorn, Imaginist Synthesis of the Arts

Firenze Architettura (2, 2018), pp. 90-95 ISSN 1826-0772 (print) | ISSN 2035-4444 (online) © The Author(s) 2018. This is an open access article distribuited under the terms of the Creative Commons License CC BY-SA 4.0 Firenze University Press DOI 10.13128/FiAr-24829 - www.fupress.com/fa/ Nel 1957, poco prima di fondare a Cosio d’Arroscia l’Internazionale Situazionista, Asger Jorn comprò due ruderi circondati da rovi sulle alture di Albissola Marina, per andarvi ad abitare. Trasformati e modellati per quasi vent’anni, i due edifici e il giardino rispecchiano l’idea di sintesi immaginista delle arti che l’artista danese ha sempre perseguito: un luogo in cui pittura e scultura sono elementi fondanti l’architettura, in una perfetta coincidenza tra forma e contenuto. In 1957, shortly before founding in Cosio d’Arroscia the Situationist International, Asger Jorn bought two ruins surrounded by brambles above Albissola Marina with the intention of living there. Transformed and modeled for almost twenty years, the two buildings and the garden reflect the idea of imaginist synthesis of the arts that the Danish artist always pursued: a place where painting and sculpture are founding elements of the architecture, in a perfect harmony between from and content. Casa Jorn, sintesi immaginista delle arti Casa Jorn, imaginist synthesis of the arts Davide Servente Nel 1954 Asger Jorn, povero e debilitato dalla tubercolosi, si tra- In 1954 Asger Jorn, impoverished and weakened by tuberculosis, sferì con la numerosa famiglia ad Albissola Marina. Il piccolo paese moved with his large family to Albissola Marina. -

Mancini, Antonio

Antonio Mancini, Self Portrait with Plate 1852 – Rome – 1930 oil on canvas 26 ½ by 19 ¼ inches (67.4 by 49 cm) signed and dated bottom right: ‘A. Mancini / di Roma’ provenance: Thomas Lawson, Boston; Scott & Fowles New York; Alvan Tufts Fuller, Boston; Colllection Pospisil , Venice; Private Collection, Milan exhibited: New York, The American Art Galleries, 1923. Milan, Villa Comunale, 1962. literature: The Thomas W. Lawson Collection / At the American Art Galleries, New York, to be sold at unrestricted public sale / in the assembly hall / of The American Art Galleries ; February 3rd, 1923; sale on thursday afternoon february 8th., n. 204 ripr.. A. Lancellotti, Antonio Mancini, Istituto Nazionale L.V.C.E. Officine dell’Istituto italiano delle Arti Grafiche, Bergamo 1931, n.10 ripr.. M. Sciuti, La malattia mentale di Antonio Mancini, Estratto del fasc. III, 1947 della Rivista “L’Ospedale Psichiatrico”, fondata da Michele Sciuti, Napoli, Tip. Ospedale Psichiatrico “L. Bianchi” 1947, pp. 42, 52, ripr 16. Mostra di Antonio Mancini, introduzione di C. Lorenzetti, presentazione di F.Bellonzi, Milano, Villa Comunale, ottobre – novembre 1962, Milano 1962, p. 36 n. 48, tav XLVIII. Antonio Mancini / Nineteenth - Century / Italian Master / Celebrating the Vance N. Jordan Collection / at the Philadelphia Museum of Art , Catalogo a cura di U. W. Hiesinger, pubblicato in occasione della mostra al Philadelphia Museum of Art, 20 ottobre 2007 – 20 gennaio 2008, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007, p. 106, nota 113. note: Antonio Mancini was one of the leading figures of nineteenth-century European painting. In his lifetime, he was admired and emulated by Italian and foreign artists and was widely acclaimed by critics and the general public. -

Export / Import: the Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2016 Export / Import: The Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969 Raffaele Bedarida Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/736 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by RAFFAELE BEDARIDA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 RAFFAELE BEDARIDA All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Emily Braun Chair of Examining Committee ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Rachel Kousser Executive Officer ________________________________ Professor Romy Golan ________________________________ Professor Antonella Pelizzari ________________________________ Professor Lucia Re THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by Raffaele Bedarida Advisor: Professor Emily Braun Export / Import examines the exportation of contemporary Italian art to the United States from 1935 to 1969 and how it refashioned Italian national identity in the process.