Venice's Giardini Della Biennale and the Geopolitics of Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Venice & the Common Ground

COVER Magazine No 02 Venice & the Common Ground Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 01 of 02 EDITORIAL 04 STATEMENTS 25 - 29 EDITORIAL Re: COMMON GROUND Reflections and reactions on the main exhibition By Pedro Gadanho, Steven Holl, Andres Lepik, Beatrice Galilee a.o. VIDEO INTERVIew 06 REPORT 30 - 31 WHAT IS »COMMON GROUND«? THE GOLDEN LIONS David Chipperfield on his curatorial concept Who won what and why Text: Florian Heilmeyer Text: Jessica Bridger PHOTO ESSAY 07 - 21 INTERVIew 32 - 39 EXCAVATING THE COMMON GROUND STIMULATORS AND MODERATORS Our highlights from the two main exhibitions Jury member Kristin Feireiss about this year’s awards Interview: Florian Heilmeyer ESSAY 22 - 24 REVIEW 40 - 41 ARCHITECTURE OBSERVES ITSELF GUERILLA URBANISM David Chipperfield’s Biennale misses social and From ad-hoc to DIY in the US Pavilion political topics – and voices from outside Europe Text: Jessica Bridger Text: Florian Heilmeyer Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 02 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 02 of 02 ReVIEW 42 REVIEW 51 REDUCE REUSE RECYCLE AND NOW THE ENSEMBLE!!! Germany’s Pavilion dwells in re-uses the existing On Melancholy in the Swiss Pavilion Text: Rob Wilson Text: Rob Wilson ESSAY 43 - 46 ReVIEW 52 - 54 OLD BUILDINGS, New LIFE THE WAY OF ENTHUSIASTS On the theme of re-use and renovation across the An exhibition that’s worth the boat ride biennale Text: Elvia Wilk Text: Rob Wilson ReVIEW 47 ESSAY 55 - 60 CULTURE UNDER CONSTRUCTION DARK SIDE CLUB 2012 Mexico’s church pavilion The Dark Side of Debate Text: Rob Wilson Text: Norman Kietzman ESSAY 48 - 50 NEXT 61 ARCHITECTURE, WITH LOVE MANUELLE GAUTRAND Greece and Spain address economic turmoil Text: Jessica Bridger Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 03 EDITORIAL Inside uncube No.2 you’ll find our selections from the 13th Architecture Biennale in Venice. -

Il Linguaggio Della Luce Secondo Vittorio Storaro MAGIC LANTERN Vittorio Storaro’S Language of Light – Paolo Calafiore

NEW BIM LIBRARY AVAILABLE 329 Luce e genius loci Park Associati Light and genius loci: Park Associati La luce nelle città Un'inchiesta Light in the cities: A reportage Vittorio Storaro Una vita per la luce Vittorio Storaro A Life in Light Outdoor LED Lighting Solutions for architecture and urban spaces. Poste ta ane spa – Sped. 1, LO/M n°46) art. 1,comma (conv. 353/2003 – D.L. n L. 27.02.2004 – n A.P. 1828-0560 SSN caribonigroup.com 2019 Anno / year 57 – n.329 2019 trimestrale / quarterly – € 15 Reverberi: innovazione nella SMART CITY TECNOLOGIE ALL’AVANGUARDIA PER CITTÀ INTELLIGENTI LTM: SENSORE LUMINANZA/TRAFFICO e condizioni metereologiche Reverberi Enetec investe nella “Computer vision” e lancia il sensore LTM. Misura della luminanza della strada monitorata, del fl usso di traffi co e delle condizioni meteo debilitanti, in particolare strada bagnata, nebbia, neve. Informazioni che, trasmesse ai sistemi della gamma Reverberi ed Opera, permettono la regolazione in tempo reale ad anello chiuso del fl usso luminoso. I test fi eld hanno dimo- strato potenzialità di risparmio energetico dell’ordine del 30%, ed aggiuntive al 25%-35% conseguibili con dispositivi di regolazione basati su cicli orari. t$POGPSNFBMMB6/*F$&/QBSUFTVJTFOTPSJEJMVNJOBO[B t$SJUFSJ"NCJFOUBMJ.JOJNJ $". EJBDRVJTUPEFMMB1VCCMJDB"NNJOJ TUSB[JPOFEFM <5065,,<967,( Reverberi Enetec srl - [email protected] - Tel 0522-610.611 Fax 0522-810.813 Via Artigianale Croce, 13 - 42035 Castelnovo né Monti - Reggio Emilia www.reverberi.it Everything comes from the project Demí With OptiLight -

Download Artist's CV

ERNESTO NETO 1964 Born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Lives and works in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Education Escola de Artes Visuais Pargua Lage, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Museu de Arte Moderna, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Solo Exhibitions 2021 SunForceOceanLife, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Mentre la vita ci respira, GAMeC, Bergamo, Italy 2020 Water Falls from my Breast to the Sky, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Chicago (permanent commission) 2019 Ernesto Neto: Sopro (Blow), Malba, Museum of Latin American Art, Buenos Aires, Argentine (traveling to Palacio de La Moneda Cultural Center, Santiago, Chile) Ernesto Neto: Children of the Earth, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, Los Angeles Ernesto Neto: Sopro (Blow), curated by Jochen Volz, Pinacoteca, São Paulo, March 30 – July 15; [traveled to Malba, Museum of Latin American Art, Buenos Aires, Argentina; Palacio de La Moneda Cultural Center, Santiago, Chile] 2018 GaiaMotherTree, Beyeler Foundation for the Zurich train station, Basel 2017 Um dia todos fomos peixes, Blue Project Foundation, Barcelona Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel Galeria, São Paulo Water Falls from my Breast to the Sky, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Chicago (permanent installation) 2016 The Serpent’s Energy Gave Birth to Humanity, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York Ernesto Neto, Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma, Helsinki, Finland Enresto Neto: Rui Ni / Voices of the Forest, KUNSTEN Museum of Modern Art Aalborg, Denmark 2015 Ernesto Neto: The Jaguar and the Boa, Kunsthalle Krems, Krems an der Donau, Austria Ernesto Neto and the Huni Kuin ~ -

Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller

JANET CARDIFF & G. B. MILLER page 61 JANET CARDIFF & GEORGE BURES MILLER Live & work in Grindrod, Canada Janet Cardiff Born in 1957, Brussels, Canada George Bures Miller Born in 1960, Vegreville, Canada AWARDS 2021 Honorary degrees, NSCAD (Nova ScoOa College of Art & Design) University, Halifax, Canada 2011 Käthe Kollwitz Prize, Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Germany 2004 Kunstpreis der Stadt Jena 2003 Gershon Iskowitz Prize 2001 Benesse Prize, 49th Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy Biennale di Venezia Special Award, 49th Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy 2000 DAAD Grant & Residency, Berlin, Germany SELECTED INDIVIDUAL EXHIBITIONS 2019 Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller, Museo de Arte Contemporaneo de Monterrey, Monterrey, Mexico 2018-2019 Janet Cardiff & Geroge Bures Miller: The Instrument of Troubled Dreams, Oude Kerk, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2018 Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller: The Poetry Machine and other works, Fraenkel Gallery, FRAENKELGALLERY.COM [email protected] JANET CARDIFF & G. B. MILLER page 62 San Francisco, CA FOREST… for a thousand years, UC Santa Cruz Arboretum and Botanic Garden, Santa Cruz, CA Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller: Two Works, SCAD Art Museum, Savannah, GA 2017-18 Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller, 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, Japan 2017 Janet Cardiff: The Forty Part Motet, Switch House at Tate Modern, London, England; Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO; Mobile Museum of Art, Mobile, AL; Auckland Castle, Durham, England; TRAFO Center for Contemporary Art, Szczecin, Poland -

Post-War & Contemporary

post-wAr & contemporAry Art Sale Wednesday, november 21, 2018 · 4 Pm · toronto i ii Post-wAr & contemPorAry Art Auction Wednesday, November 21, 2018 4 PM Post-War & Contemporary Art 7 PM Canadian, Impressionist & Modern Art Design Exchange The Historic Trading Floor (2nd floor) 234 Bay Street, Toronto Located within TD Centre Previews Heffel Gallery, Calgary 888 4th Avenue SW, Unit 609 Friday, October 19 through Saturday, October 20, 11 am to 6 pm Heffel Gallery, Vancouver 2247 Granville Street Saturday, October 27 through Tuesday, October 30, 11 am to 6 pm Galerie Heffel, Montreal 1840 rue Sherbrooke Ouest Thursday, November 8 through Saturday, November 10, 11 am to 6 pm Design Exchange, Toronto The Exhibition Hall (3rd floor), 234 Bay Street Located within TD Centre Saturday, November 17 through Tuesday, November 20, 10 am to 6 pm Wednesday, November 21, 10 am to noon Heffel Gallery Limited Heffel.com Departments Additionally herein referred to as “Heffel” consignments or “Auction House” [email protected] APPrAisAls CONTACT [email protected] Toll Free 1-888-818-6505 [email protected], www.heffel.com Absentee And telePhone bidding [email protected] toronto 13 Hazelton Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M5R 2E1 shiPPing Telephone 416-961-6505, Fax 416-961-4245 [email protected] ottAwA subscriPtions 451 Daly Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario K1N 6H6 [email protected] Telephone 613-230-6505, Fax 613-230-8884 montreAl CatAlogue subscriPtions 1840 rue Sherbrooke Ouest, Montreal, Quebec H3H 1E4 Heffel Gallery Limited regularly publishes a variety of materials Telephone 514-939-6505, Fax 514-939-1100 beneficial to the art collector. -

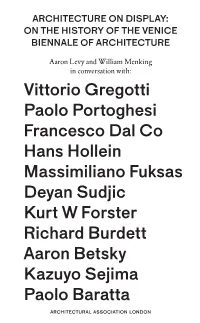

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

Listed Exhibitions (PDF)

G A G O S I A N G A L L E R Y Anish Kapoor Biography Born in 1954, Mumbai, India. Lives and works in London, England. Education: 1973–1977 Hornsey College of Art, London, England. 1977–1978 Chelsea School of Art, London, England. Solo Exhibitions: 2016 Anish Kapoor. Gagosian Gallery, Hong Kong, China. Anish Kapoor: Today You Will Be In Paradise. Gladstone Gallery, New York, NY. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, London, England. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, Milan, Italy. Anish Kapoor. Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, Mexico City, Mexico. 2015 Descension. Galleria Continua, San Gimignano, Italy. Anish Kapoor. Regen Projects, Los Angeles, CA. Kapoor Versailles. Gardens at the Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France. Anish Kapoor. Gladstone Gallery, Brussels, Belgium. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, London, England. Anish Kapoor: Prints from the Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer. Portland Art Museum, Portland, OR. Anish Kapoor chez Le Corbusier. Couvent de La Tourette, Eveux, France. Anish Kapoor: My Red Homeland. Jewish Museum and Tolerance Centre, Moscow, Russia. 2013 Anish Kapoor in Instanbul. Sakıp Sabancı Museum, Istanbul, Turkey. Anish Kapoor Retrospective. Martin Gropius Bau, Berlin, Germany 2012 Anish Kapoor. Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia. Anish Kapoor. Gladstone Gallery, New York, NY. Anish Kapoor. Leeum – Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea. Anish Kapoor, Solo Exhibition. PinchukArtCentre, Kiev, Ukraine. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, London, England. Flashback: Anish Kapoor. Longside Gallery, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Bretton, England. Anish Kapoor. De Pont Foundation for Contemporary Art, Tilburg, Netherlands. 2011 Anish Kapoor: Turning the Wold Upside Down. Kensington Gardens, London, England. Anish Kapoor: Flashback. Nottingham Castle Museum, Nottingham, England. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

Shifting Perspectives in the Venice Biennale's Hungarian Exhibition

17 Looking Forwards or Back? Shifting Perspectives in the Venice Biennale’s Hungarian Exhibition: 1928 and 1948 KINGA BÓDI 268 Kinga Bódi Kinga Bódi, PhD, is curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. As a doctoral fellow at the Swiss Institute for Art Research (SIK–ISEA) she investigated the cultural representation of Hungary at the Venice Biennale from its beginnings until 1948. In her present essay, Bódi jointly discusses the frst contemporary avant-garde Hungarian show in Venice in 1928 and the Biennale edition of 1948, which she interprets as a counterpoint of sorts to the one twenty years earlier, defned by conservative ideological principles and neo-Classicism. Her study examines the historical, social, cultural, political, artistic, professional, and personal background of these two specifc years of Hungarian participation in Venice. At the same time, her essay contributes to current international dialogues on the changing role of international exhibitions, curatorial activities, and (museum) collections. (BH) Looking Forwards or Back? Shifting Perspectives in the Venice Biennale’s Hungarian Exhibition: 1928 and 19481 From 1895 to 1948, it was self-evident that Hungary would take part in the Venice Biennale. During this period, the country too kept in step, more or less, with the artistic and conceptual changes that governed the Biennale, virtually the sole major international exhibition opportunity for Hungarian artists then and now. Tis is perhaps why, for the 124 years since the frst participation, the question of the Hungarian Pavilion has remained at the centre of domestic art-scene debates. Comparing nations has always been a facet of the Venice Biennale. -

Antonio Prieto; » Julio Aè Pared 30 a Craftsman5 Ipko^Otonmh^

Until you see and feel Troy Weaving Yarns . you'll find it hard to believe you can buy such quality, beauty and variety at such low prices. So please send for your sample collection today. and Textile Company $ 1.00 brings you a generous selection of the latest and loveliest Troy quality controlled yarns. You'll find new 603 Mineral Spring Avenue, Pawtucket, R. I. 02860 pleasure and achieve more beautiful results when you weave with Troy yarns. »««Él Mm m^mmrn IS Dialogue .n a « 23 Antonio Prieto; » Julio Aè Pared 30 A Craftsman5 ipKO^OtONMH^ IS«« MI 5-up^jf à^stoneware "iactogram" vv.i is a pòìnt of discussion in Fred-Schwartz's &. Countercues A SHOPPING CENTER FOR JEWELRY CRAFTSMEN at your fingertips! complete catalog of... TOOLS AND SUPPLIES We've spent one year working, compiling and publishing our new 244-page Catalog 1065 ... now it is available. In the fall of 1965, the Poor People's Corporation, a project of the We're mighty proud of this new one... because we've incor- SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), sought skilled porated brand new never-before sections on casting equipment, volunteer craftsmen for training programs in the South. At that electroplating equipment and precious metals... time, the idea behind the program was to train local people so that they could organize cooperative workshops or industries that We spent literally months redesigning the metals section . would help give them economic self-sufficiency. giving it clarity ... yet making it concise and with lots of Today, PPC provides financial and technical assistance to fifteen information.. -

56Th Venice Biennale—Main Exhibition, National Pavilions, Off-Site and Museums

56th Venice Biennale—Main exhibition, National Pavilions, Off-Site and Museums by Chris Sharp May 2015 Adrian Ghenie, Darwin and the Satyr, 2014. Okay, in the event that you, dear reader(s), are not too tired of the harried Venice musings of the art-agenda corps rearing up in your inbox, here’s a final reflection. Allow me to start with an offensively obvious observation. In case you haven’t noticed, Venice is not particularly adapted to the presentation of contemporary art. In fact, this singular city is probably the least appropriate place to show contemporary art, or art of any kind, and this is from a totally practical point of view. From the aquatic transportation of works to questions of humidity to outmoded issues of national representation, Venice is not merely an anachronism but also, and perhaps more importantly, a point of extravagance without parallel in the global art-circuit calendar. When you learn how much it costs to get on the map even as a collateral event, you understand that the sheer mobilization of monies and resources that attends this multifarious, biannual event is categorically staggering. This mobilization is far from limited to communication as well as the production and transportation of art, but also includes lodging, dinners, and parties. For example, the night of my arrival, I found myself at a dinner for 400 people in a fourteenth-century palazzo. Given in honor of one artist, it was bankrolled by her four extremely powerful galleries, who, if they want to remain her galleries and stay in the highest echelons of commercial power, must massively throw down for this colossal repast and subsequent party, on top of already, no doubt, jointly co-funding the production of her pavilion, while, incidentally, co-funding other dinners, parties, and so on and so forth. -

1 Eötvös Loránd University Faculty of Humanities Doctoral School of Art

Eötvös Loránd University Faculty of Humanities Doctoral School of Art History Prof. Dr. György Kelényi Professor Emeritus Leader of the Art History Doctoral Program SUMMARY OF DOCTORAL (PhD) DISSERTATION 2014 Kinga Bódi Hungarian Participation at the Venice Art Biennale 1895–1948 Doctoral Supervisors: Dr. Annamária Szőke PhD Prof. Dr. Beat Wyss PhD Appointed Doctoral Reviewers: Dr. Ágnes Prékopa PhD Dr. Ferenc Gosztonyi PhD Members of the Doctoral Committee: Prof. Dr. Katalin Keserü Professor Emeritus, Chair Dr. Julianna Ágoston PhD, Secretary Dr. Julianna P. Szűcs PhD, Member Dr. Anna Eörsi PhD, Replacement Member Dr. Mária Prokopp PhD, Replacement Member 1 Research Background As a student of the Doctoral School of Art History at Eötvös Loránd University Faculty of Humanities, between 2010 and 2013 I had the possibility to participate with my research subject in a three-year international art history research program titled Fokus Projekt «Kunstbetrieb» – Biennale Projekt, sponsored by the Schweizerisches Institut für Kunstwissenschaft in Zurich. The head of the research group was Prof. Dr. Beat Wyss, professor of art history at the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Karlsruhe (HfG). The idea to launch a research project in 2010 based on the unique history of the Venice Biennale, the oldest art biennial of the world and its specially constructed system of international pavilions was in part triggered by the existing monographs on international participation and also by an approach based on Niklas Luhmann’s (1927-1998) culture theory, which regarded the Biennale as one of the most significant “artistic structures” or “art factories” of the world, as well as by the popular exhibition reconstruction research projects of our time.