Report on Futures Past Editor's Note Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Venice's Giardini Della Biennale and the Geopolitics of Architecture

FOLKLORIC MODERNISM: VENICE’S GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE AND THE GEOPOLITICS OF ARCHITECTURE Joel Robinson This paper considers the national pavilions of the Venice Biennale, the largest and longest running exposition of contemporary art. It begins with an investigation of the post-fascist landscape of Venice’s Giardini della Biennale, whose built environment continued to evolve in the decades after 1945 with the construction of several new pavilions. With a view to exploring the architectural infrastructure of an event that has always billed itself as ‘international’, the paper asks how the mapping of national pavilions in this context might have changed to reflect the supposedly post-colonial and democratic aspirations of the West after the Second World War. Homing in on the nations that gained representation here in the 1950s and 60s, it looks at three of the more interesting architectural additions to the gardens: the pavilions for Israel, Canada and Brazil. These raise questions about how national pavilions are mobilised ideologically, and form/provide the basis for a broader exploration of the geopolitical superstructure of the Biennale as an institution. Keywords: pavilion, Venice Biennale, modernism, nationalism, geopolitics, postcolonialist. Joel Robinson, The Open University Joel Robinson is a Research Affiliate in the Department of Art History at the Open University and an Associate Lecturer for the Open University in the East of England. His main interests are modern and contemporary art, architecture and landscape studies. He is the author of Life in Ruins: Architectural Culture and the Question of Death in the Twentieth Century (2007), which stemmed from his doctoral work in art history at the University of Essex, and he is co-editor of a new anthology in art history titled Art and Visual Culture: A Reader (2012). -

Orshi Drozdik

Press release ORSHI DRODZIK It’s All Over Now Baby Blue Opening Wednesday October 2th from 18.00 to 20.00 in presence of the artist Exhibition October 2 - November 27,2013 The Gandy gallery is pleased to announce the first solo exhibition by Orshi Drodzik at the gallery in Bratislava. The work of Orshi Drozdik (b,1946,Hungary) has played a significant role in the history of women’s art across the international arts scene and has greatly influenced a generation of artists to follow. Drozdik moved to Amsterdam in 1978, after graduating from the College of Fine Arts, in 1977 as a graphics major, and two years later she based herself in New York City. At present Drozdik works both in New York and Budapest, and is a professor at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts. She has exhibited at many of the foremost galleries across Hungary and abroad, and articles assessing her shows have been published in numerous prestigious art journals. Yet, Drozdik has continually engaged with the contemporary art scene in Hungary. The 1998 exhibition, article, and textbook titled Strolling Brains, for instance, greatly contributed to the spread of feminism in the country. Drozdik began her career in tandem with the Hungarian post-conceptual movement of the 1970s. As a harbinger she created her own theoretical and critical point of view, which was unique in the seventies cultural environment of Budapest. In the 80s, at the time of her emigration, building upon of her 70s working methode, she embraced poststructuralist critical discourse, that helped her to develop, the installation series, Adventure in Technos Dystopium, a theoretical and visual deconstruction of scientific representation. -

Új Művészet, 2003, 24

október 2019 9 ISSN 0866-2185 765 Ft 19009 9 770866 218000 október Felforgatók: Felforgatók: Schwitters, Schnabel, KirályTót, 2019 szürrealisták a Magyar Nemzeti Galériában Andalúziai kutyából nem lesz szalonna: Andalúziai nem kutyából lesz szalonna: 9 A A Hantai-siker nyomában Őszi lehalászás MűtÁRGYBEFEKTETÉSI M. NOVÁK ANDR ÁS Munkácsy Mihály-díjas festőművész, az MMA rendes tagja kiállítása KONFERENCIA 2019. OKTÓBER 2. NOVEMBER 10. 2019. november 12. P E S T I V I G A D Ó , a Magyar Művészeti Akadémia székháza, Müpa, Auditorium V. emeleti kiállítóterem Budapest V. kerület, Vigadó tér 2. www.mutargykonferencia.hu OGATÓ M SZERVEZő FőTÁ minden, ami művészet mma.hu október 2019 9 Anadalúziai kutyából nem lesz szalonna Favicc A festészet többet tud, mint a fotó Kiváló holttestek diétás menüben Klaus Littmann: For Forest – The Unending Beszélgetés Székely Annamária Attraction of Nature 28 háromdimenziós kísérleteiről 46 A szürrealista mozgalom Dalítól Magritte-ig 4 TAYLER PATRICK NICHOLAS——— MULADI BRIGITTA——— GYőRFFY LÁSZLÓ———— Absztrakt kalandok Dimenziók Felforgatók Egy siker anatómiája A tér lebontása A MAOE VI. tematikus kiállítása 48 A Hantai-szerződés hazai vonatkozásai 31 D. UDVARY IldIKÓ——— Kurt Schwitters Merz-katedrálisa 10 MÉSZÁROS FLÓRA——— LESI ZOLTÁN——— Olvasó Kék-arany ragyogások Emlékül, ismerni akaróknak Ropogós, zamatos, fanyar nyomatok Molnár László festményeiről 34 E. Csorba Csilla – Sipőcz Mariann: Arany Julian Schnabel grafikái 13 LÓSKA LAJOS——— János és a fényképezés. Országh Antal TOLNAY IMRE——— fotográfus (1821–1878) -

Friends, 2020 Catalog

FRIENDS, 2020 KATARZYNA KOZYRA FOUNDATION SUPPORT PROGRAM the present times are challenging for everybody. Even more so for women. The spread of the coronavirus and the worldwide economic crisis will make our work more difficult still. But we don’t give up. We will continue to fight in defence of the freedom of thought and gender equality. The Katarzyna Kozyra Foundation, as you know, has been created to support the work of female artists. Its many initiatives included, for example, a series of exhibitions of Women Commentators – a project which gave voice to young Russian and Ukrainian artists who live in countries where freedom of expression is not always allowed. One of the most recent investigations that the Foundation carried out, Little Chance to Advance, has revealed the huge underrepresentation of female teachers in Polish Art Academies. The Foundation is also currently working on numerous projects, which include an exhibition of Urszula Broll, a recently deceased artist who unfortunately did not live to see sufficient recognition for the important work of her life, as well as an archive of statements and works by female artists from the Visegrad Group. The recent cuts in the financing of NGO’s providing social and cultural support for women, make the raison d’ être of the Katarzyna Kozyra Foundation even more justified. It is why I ask you to join the group of the Foundation’s Friends and support us with a financial contribution so as to help the Foundation implement its program in support for women artists, consisting of research projects, exhibitions, book publications, seminars… I do not ask you for this commitment in exchange for nothing. -

The Art of Performance a Critical Anthology

THE ART OF PERFORMANCE A CRITICAL ANTHOLOGY edited by GREGORY BATTCOCK AND ROBERT NICKAS /ubu editions 2010 The Art of Performance A Critical Anthology 1984 Edited By: Gregory Battcock and Robert Nickas /ubueditions ubu.com/ubu This UbuWeb Edition edited by Lucia della Paolera 2010 2 The original edition was published by E.P. DUTTON, INC. NEW YORK For G. B. Copyright @ 1984 by the Estate of Gregory Battcock and Robert Nickas All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper or broadcast. Published in the United States by E. P. Dutton, Inc., 2 Park Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10016 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 79-53323 ISBN: 0-525-48039-0 Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Toronto 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition Vito Acconci: "Notebook: On Activity and Performance." Reprinted from Art and Artists 6, no. 2 (May l97l), pp. 68-69, by permission of Art and Artists and the author. Russell Baker: "Observer: Seated One Day At the Cello." Reprinted from The New York Times, May 14, 1967, p. lOE, by permission of The New York Times. Copyright @ 1967 by The New York Times Company. -

Orshi Drozdik Adventure & Appropriation 1975 - 2001 Drozdikorshi-Katalogus01.Qxd 2002

drozdikorshi-katalogus01.qxd 2002. 11. 21. 14:51 Page 1 (Black plate) Orshi Drozdik Adventure & Appropriation 1975 - 2001 drozdikorshi-katalogus01.qxd 2002. 11. 21. 14:51 Page 3 (Black plate) Orshi Drozdik Adventure & Appropriation 1975 - 2001 Ludwig Museum Budapest – Museum of Contemporary Art 2002 Budapest drozdikorshi-katalogus01.qxd 2002. 11. 21. 14:51 Page 5 (Black plate) DESIRE HIDES IN GAZE A Retrospective of Orshi Drozdik “Desire hides in gaze. Desire is one of our most powerful driving forces. Our way of seeing and our art are formed by that and reflect on our desire” – said Orshi Drozdik in a recent interview concern- ing the topic of female identity and the use of her own body as a model and subject matter. Inevitably, she was the first Hungarian artist, who researched and introduced the female aspect in her work, and who intended to summarize the already existing but fragmented endeavours in this field, and who even edited a book (Walking Brains) with writings by leading authors of feminist theory. She always regarded her artistic program as a mission, which is rooted in her Hungarian experience but obviously became more conscious and sophisticated by the knowledge she gained while living abroad. This is the first time that we can follow Orshi Drozdik’s professional career, which began in the seventies with performances, photo series, graphic works, and continued with powerful figural paintings and installations. Even at this early stage, her obsession with the human body was evident. Later, while living in Amsterdam and New York, she began an investigation of such diverse subjects as the utopists of the French Enlightenment, the history of medicine, and the botanical taxonomic system of Carolus Linnaeus. -

Shifting Perspectives in the Venice Biennale's Hungarian Exhibition

17 Looking Forwards or Back? Shifting Perspectives in the Venice Biennale’s Hungarian Exhibition: 1928 and 1948 KINGA BÓDI 268 Kinga Bódi Kinga Bódi, PhD, is curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. As a doctoral fellow at the Swiss Institute for Art Research (SIK–ISEA) she investigated the cultural representation of Hungary at the Venice Biennale from its beginnings until 1948. In her present essay, Bódi jointly discusses the frst contemporary avant-garde Hungarian show in Venice in 1928 and the Biennale edition of 1948, which she interprets as a counterpoint of sorts to the one twenty years earlier, defned by conservative ideological principles and neo-Classicism. Her study examines the historical, social, cultural, political, artistic, professional, and personal background of these two specifc years of Hungarian participation in Venice. At the same time, her essay contributes to current international dialogues on the changing role of international exhibitions, curatorial activities, and (museum) collections. (BH) Looking Forwards or Back? Shifting Perspectives in the Venice Biennale’s Hungarian Exhibition: 1928 and 19481 From 1895 to 1948, it was self-evident that Hungary would take part in the Venice Biennale. During this period, the country too kept in step, more or less, with the artistic and conceptual changes that governed the Biennale, virtually the sole major international exhibition opportunity for Hungarian artists then and now. Tis is perhaps why, for the 124 years since the frst participation, the question of the Hungarian Pavilion has remained at the centre of domestic art-scene debates. Comparing nations has always been a facet of the Venice Biennale. -

1 Eötvös Loránd University Faculty of Humanities Doctoral School of Art

Eötvös Loránd University Faculty of Humanities Doctoral School of Art History Prof. Dr. György Kelényi Professor Emeritus Leader of the Art History Doctoral Program SUMMARY OF DOCTORAL (PhD) DISSERTATION 2014 Kinga Bódi Hungarian Participation at the Venice Art Biennale 1895–1948 Doctoral Supervisors: Dr. Annamária Szőke PhD Prof. Dr. Beat Wyss PhD Appointed Doctoral Reviewers: Dr. Ágnes Prékopa PhD Dr. Ferenc Gosztonyi PhD Members of the Doctoral Committee: Prof. Dr. Katalin Keserü Professor Emeritus, Chair Dr. Julianna Ágoston PhD, Secretary Dr. Julianna P. Szűcs PhD, Member Dr. Anna Eörsi PhD, Replacement Member Dr. Mária Prokopp PhD, Replacement Member 1 Research Background As a student of the Doctoral School of Art History at Eötvös Loránd University Faculty of Humanities, between 2010 and 2013 I had the possibility to participate with my research subject in a three-year international art history research program titled Fokus Projekt «Kunstbetrieb» – Biennale Projekt, sponsored by the Schweizerisches Institut für Kunstwissenschaft in Zurich. The head of the research group was Prof. Dr. Beat Wyss, professor of art history at the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Karlsruhe (HfG). The idea to launch a research project in 2010 based on the unique history of the Venice Biennale, the oldest art biennial of the world and its specially constructed system of international pavilions was in part triggered by the existing monographs on international participation and also by an approach based on Niklas Luhmann’s (1927-1998) culture theory, which regarded the Biennale as one of the most significant “artistic structures” or “art factories” of the world, as well as by the popular exhibition reconstruction research projects of our time. -

Ecart Publications (1973-1982) Ou La Mise En Circulation De L’Art Dans Le Livre

Unicentre CH-1015 Lausanne http://serval.unil.ch 2020 Anatomie d’une imprimerie : Ecart Publications (1973-1982) ou la mise en circulation de l’art dans le livre Pierre-Paul Bianchi Pierre-Paul Bianchi, 2020, Anatomie d’une imprimerie : Ecart Publications (1973-1982) ou la mise en circulation de l’art dans le livre Originally published at : Mémoire de maîtrise, Université de Lausanne Posted at the University of Lausanne Open Archive. http://serval.unil.ch Droits d’auteur L'Université de Lausanne attire expressément l'attention des utilisateurs sur le fait que tous les documents publiés dans l'Archive SERVAL sont protégés par le droit d'auteur, conformément à la loi fédérale sur le droit d'auteur et les droits voisins (LDA). A ce titre, il est indispensable d'obtenir le consentement préalable de l'auteur et/ou de l’éditeur avant toute utilisation d'une oeuvre ou d'une partie d'une oeuvre ne relevant pas d'une utilisation à des fins personnelles au sens de la LDA (art. 19, al. 1 lettre a). A défaut, tout contrevenant s'expose aux sanctions prévues par cette loi. Nous déclinons toute responsabilité en la matière. Copyright The University of Lausanne expressly draws the attention of users to the fact that all documents published in the SERVAL Archive are protected by copyright in accordance with federal law on copyright and similar rights (LDA). Accordingly it is indispensable to obtain prior consent from the author and/or publisher before any use of a work or part of a work for purposes other than personal use within the meaning of LDA (art. -

How the Finnish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale Had to Change Into a Black Box for Contemporary Video Art and How It Became a Symbol for Artists to Defeat

Alvar Aalto Researchers’ Network Seminar – Why Aalto? 9-10 June 2017, Jyväskylä, Finland Against Aalto: How the Finnish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale had to change into a black box for contemporary video art and how it became a symbol for artists to defeat Gianni Talamini architect, PhD Department of Architecture & Civil Engineering City University of Hong Kong Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon, Hong Kong P6424 AC1 Tel: (852) 3442 7618 Email: [email protected] Title Against Aalto: how the Finnish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale had to change into a black box for contemporary video art and how it became a symbol for artists to defeat. Abstract The Finnish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale has hosted more than 30 exhibitions since its construction in 1956. Alvar Aalto designed the space as a temporary structure to display conventional Finnish visual art, such as the work of Helene Schjerfbeck. Although being relatively short, the history of the pavilion has been very eventful. The original plan for a temporary building to be dismantled and rebuilt every second year was not followed. Soon after its construction the pavilion instead went through a period of semi- abandonment, being used as a storage space and green house. Only the death of its designer in 1976 brought interest from the general public back to the pavilion for a short time. In the 1990s the dedicated work of Finnish scholars contributed crucially to the conservation both of the building and its history. After the 2000s Finland again started to use the pavilion as a national exhibition space. -

Kideritetlen (Marad)

GENDERED ARTISTIC POSITIONS AND SOCIAL VOICES: POLITICS, CINEMA, AND THE VISUAL ARTS IN STATE-SOCIALIST AND POST-SOCIALIST HUNGARY by Beáta Hock Submitted to the Department of Gender Studies, Central European University, Budapest In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Professor Susan Zimmermann CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2009 CEU eTD Collection DECLARATION I hereby declare that no parts of this thesis have been submitted towards a degree at any other institution other than CEU, nor, to my knowledge, does the thesis contain unreferenced material or ideas from other authors. Beáta Hock CEU eTD Collection CEU eTD Collection ABSTRACT The aim of this dissertation has been to explore what factors shaped artistic representations of women and the artistic agendas and self-positioning of individual women cultural producers in Hungary’s state-socialist and post-socialist periods. In using gender as an analytical category within the framework of a carefully conceptualized East/West comparison as well as a state- socialist/post-socialist comparison, the thesis historicizes and contextualizes gender in multidimensional ways. Positing that particular state formations and the dominant ideologies therein interpellate individuals in particular ways and thus might better enable certain subjectivites and constrain others, the thesis sets out to identify the kind of messages that the two different political systems in Hungary communicated to women in general through their political discourses, actual legislation, and social policies. Within this socio-historical framing, the research traces how female subject positions emerge in the respective periods, and turn into speaking positions with women cultural producers in the specific fields of cinema and the visual arts. -

Fluxus Reader By: Ken Friedman Edited by Ken Friedman ISBN: 0471978582 See Detail of This Book on Amazon.Com

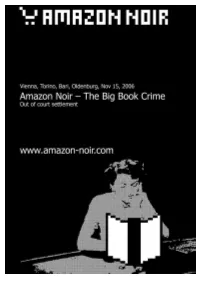

The Fluxus Reader By: Ken Friedman Edited by Ken Friedman ISBN: 0471978582 See detail of this book on Amazon.com Book served by AMAZON NOIR (www.amazon-noir.com) project by: PAOLO CIRIO paolocirio.net UBERMORGEN.COM ubermorgen.com ALESSANDRO LUDOVICO neural.it Page 1 PART I THREE HISTORIESPART I THREE HISTORIESPART I THREE HISTORIES Page 2 Page 3 Ben Patterson, Terry Reilly and Emmett Williams, of whose productions we will see this evening, pursue purposes already completely separate from Cage, though they have, however, a respectful affection.' After this introduction the concert itself began with a performance of Ben Patterson's Paper Piece. Two performers entered the stage from the wings carrying a large 3'x15' sheet of paper, which they then held over the heads of the front of the audience. At the same time, sounds of crumpling and tearing paper could be heard from behind the on-stage paper screen, in which a number of small holes began to appear. The piece of paper held over the audience's heads was then dropped as shreds and balls of paper were thrown over the screen and out into the audience. As the small holes grew larger, performers could be seen behind the screen. The initial two performers carried another large sheet out over the audience and from this a number of printed sheets of letter-sized paper were dumped onto the audience. On one side of these sheets was a kind of manifesto: "PURGE the world of bourgeois sickness, `intellectual', professional & commercialised culture, PURGE the world of dead art, imitation, artificial art, abstract art, illusionistic Page 4 [...] FUSE the cadres of cultural, social & political revolutionaries into united front & action."2 The performance of Paper Piece ended as the paper screen was gradually torn to shreds, leaving a paper-strewn stage.