Loom Gallery Via Marsala, 7 20121 Milano It +39 02 8706 4323 [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Új Művészet, 2003, 24

október 2019 9 ISSN 0866-2185 765 Ft 19009 9 770866 218000 október Felforgatók: Felforgatók: Schwitters, Schnabel, KirályTót, 2019 szürrealisták a Magyar Nemzeti Galériában Andalúziai kutyából nem lesz szalonna: Andalúziai nem kutyából lesz szalonna: 9 A A Hantai-siker nyomában Őszi lehalászás MűtÁRGYBEFEKTETÉSI M. NOVÁK ANDR ÁS Munkácsy Mihály-díjas festőművész, az MMA rendes tagja kiállítása KONFERENCIA 2019. OKTÓBER 2. NOVEMBER 10. 2019. november 12. P E S T I V I G A D Ó , a Magyar Művészeti Akadémia székháza, Müpa, Auditorium V. emeleti kiállítóterem Budapest V. kerület, Vigadó tér 2. www.mutargykonferencia.hu OGATÓ M SZERVEZő FőTÁ minden, ami művészet mma.hu október 2019 9 Anadalúziai kutyából nem lesz szalonna Favicc A festészet többet tud, mint a fotó Kiváló holttestek diétás menüben Klaus Littmann: For Forest – The Unending Beszélgetés Székely Annamária Attraction of Nature 28 háromdimenziós kísérleteiről 46 A szürrealista mozgalom Dalítól Magritte-ig 4 TAYLER PATRICK NICHOLAS——— MULADI BRIGITTA——— GYőRFFY LÁSZLÓ———— Absztrakt kalandok Dimenziók Felforgatók Egy siker anatómiája A tér lebontása A MAOE VI. tematikus kiállítása 48 A Hantai-szerződés hazai vonatkozásai 31 D. UDVARY IldIKÓ——— Kurt Schwitters Merz-katedrálisa 10 MÉSZÁROS FLÓRA——— LESI ZOLTÁN——— Olvasó Kék-arany ragyogások Emlékül, ismerni akaróknak Ropogós, zamatos, fanyar nyomatok Molnár László festményeiről 34 E. Csorba Csilla – Sipőcz Mariann: Arany Julian Schnabel grafikái 13 LÓSKA LAJOS——— János és a fényképezés. Országh Antal TOLNAY IMRE——— fotográfus (1821–1878) -

The Art of Performance a Critical Anthology

THE ART OF PERFORMANCE A CRITICAL ANTHOLOGY edited by GREGORY BATTCOCK AND ROBERT NICKAS /ubu editions 2010 The Art of Performance A Critical Anthology 1984 Edited By: Gregory Battcock and Robert Nickas /ubueditions ubu.com/ubu This UbuWeb Edition edited by Lucia della Paolera 2010 2 The original edition was published by E.P. DUTTON, INC. NEW YORK For G. B. Copyright @ 1984 by the Estate of Gregory Battcock and Robert Nickas All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper or broadcast. Published in the United States by E. P. Dutton, Inc., 2 Park Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10016 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 79-53323 ISBN: 0-525-48039-0 Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Toronto 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition Vito Acconci: "Notebook: On Activity and Performance." Reprinted from Art and Artists 6, no. 2 (May l97l), pp. 68-69, by permission of Art and Artists and the author. Russell Baker: "Observer: Seated One Day At the Cello." Reprinted from The New York Times, May 14, 1967, p. lOE, by permission of The New York Times. Copyright @ 1967 by The New York Times Company. -

Report on Futures Past Editor's Note Table of Contents

Report on the Construction of tranzit j a n 2 2 – a p r 1 3 , 2 0 1 4 a Spaceship Module new museum REPORT ON FUTURES PAST Lauren Cornell fantasies from the socialist side of the Iron tors worked on this exhibition: Vít Havránek, Director of tranzit in Prague, Dóra Curtain. As depictions of the future are always Hegyi, Director of tranzit in Budapest, and Georg Schöllhammer, Director of tranzit deeply tied to the moments in which they are in Vienna. Much like the Museum as Hub program (the New Museum’s interna- conceived, the craft also symbolizes numerous tional partnership through which the exhibition is produced), tranzit organizations realities flattened out and stitched together or actively collaborate with each other, but also work independently to produce art “come back to haunt,”1 as Philip K. Dick has historical research, exhibitions, and new commissions. The work included in this written, all within one seamless vessel. exhibition—all made by artists that tranzit has worked with in some capacity or, alternately, documentation of events or exhibitions tranzit has staged—consti- “Report on the Construction of a Spaceship tutes an “innovative archive”2 of their organization. Module” is an exhibition about art’s movement across time and space. The featured artworks, Across poetry, performative actions, diagrammatic schemas, avatars, found made by artists mainly from former Eastern objects, collections of photographs, and architectural models, “Report on the Bloc countries over the past sixty years, draw Construction of a Spaceship Module” reflects tranzit’s efforts to gather, remember, from a vast breadth of historic periods and and argue for art within Eastern Europe, and its porous connections to art outside artistic movements. -

Ecart Publications (1973-1982) Ou La Mise En Circulation De L’Art Dans Le Livre

Unicentre CH-1015 Lausanne http://serval.unil.ch 2020 Anatomie d’une imprimerie : Ecart Publications (1973-1982) ou la mise en circulation de l’art dans le livre Pierre-Paul Bianchi Pierre-Paul Bianchi, 2020, Anatomie d’une imprimerie : Ecart Publications (1973-1982) ou la mise en circulation de l’art dans le livre Originally published at : Mémoire de maîtrise, Université de Lausanne Posted at the University of Lausanne Open Archive. http://serval.unil.ch Droits d’auteur L'Université de Lausanne attire expressément l'attention des utilisateurs sur le fait que tous les documents publiés dans l'Archive SERVAL sont protégés par le droit d'auteur, conformément à la loi fédérale sur le droit d'auteur et les droits voisins (LDA). A ce titre, il est indispensable d'obtenir le consentement préalable de l'auteur et/ou de l’éditeur avant toute utilisation d'une oeuvre ou d'une partie d'une oeuvre ne relevant pas d'une utilisation à des fins personnelles au sens de la LDA (art. 19, al. 1 lettre a). A défaut, tout contrevenant s'expose aux sanctions prévues par cette loi. Nous déclinons toute responsabilité en la matière. Copyright The University of Lausanne expressly draws the attention of users to the fact that all documents published in the SERVAL Archive are protected by copyright in accordance with federal law on copyright and similar rights (LDA). Accordingly it is indispensable to obtain prior consent from the author and/or publisher before any use of a work or part of a work for purposes other than personal use within the meaning of LDA (art. -

Fluxus Reader By: Ken Friedman Edited by Ken Friedman ISBN: 0471978582 See Detail of This Book on Amazon.Com

The Fluxus Reader By: Ken Friedman Edited by Ken Friedman ISBN: 0471978582 See detail of this book on Amazon.com Book served by AMAZON NOIR (www.amazon-noir.com) project by: PAOLO CIRIO paolocirio.net UBERMORGEN.COM ubermorgen.com ALESSANDRO LUDOVICO neural.it Page 1 PART I THREE HISTORIESPART I THREE HISTORIESPART I THREE HISTORIES Page 2 Page 3 Ben Patterson, Terry Reilly and Emmett Williams, of whose productions we will see this evening, pursue purposes already completely separate from Cage, though they have, however, a respectful affection.' After this introduction the concert itself began with a performance of Ben Patterson's Paper Piece. Two performers entered the stage from the wings carrying a large 3'x15' sheet of paper, which they then held over the heads of the front of the audience. At the same time, sounds of crumpling and tearing paper could be heard from behind the on-stage paper screen, in which a number of small holes began to appear. The piece of paper held over the audience's heads was then dropped as shreds and balls of paper were thrown over the screen and out into the audience. As the small holes grew larger, performers could be seen behind the screen. The initial two performers carried another large sheet out over the audience and from this a number of printed sheets of letter-sized paper were dumped onto the audience. On one side of these sheets was a kind of manifesto: "PURGE the world of bourgeois sickness, `intellectual', professional & commercialised culture, PURGE the world of dead art, imitation, artificial art, abstract art, illusionistic Page 4 [...] FUSE the cadres of cultural, social & political revolutionaries into united front & action."2 The performance of Paper Piece ended as the paper screen was gradually torn to shreds, leaving a paper-strewn stage. -

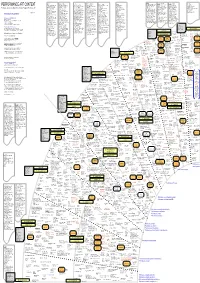

Performance Art Context R

Literature: Literature: (...continued) Literature: Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Kunstf. Bd.137 / Atlas der Künstlerreisen Literature: (...continued) Literature: (... continued) Richard Kostelnatz / The Theater of Crossings (catalogue) E. Jappe / Performance Ritual Prozeß Walking through society (yearbook) ! Judith Butler !! / Bodies That Matter Victoria Best & Peter Collier (Ed.) / article: Kultur als Handlung Kunstf. Bd.136 / Ästhetik des Reisens Butoh – Die Rebellion des Körpers PERFORMANCE ART CONTEXT R. Shusterman / Kunst leben – Die Ästhetik Mixed Means. An Introduction to Zeitspielräume. Performance Musik On Ritual (Performance Research) Eugenio Barber (anthropological view) Performative Acts and Gender Constitution Powerful Bodies – Performance in French Gertrude Koch Zeit – Die vierte Dimension in der (Kazuo Ohno, Carlotta Ikeda, Tatsumi des Pragmatismus Happenings, Kinetic Environments ... ! Ästhetik / Daniel Charles Richard Schechner / Future of Ritual Camille Camillieri (athropolog. view; (article 1988!) / Judith Butler Cultural Studies !! Mieke Bal (lecture) / Performance and Mary Ann Doane / Film and the bildenden Kunst Hijikata, Min Tanaka, Anzu Furukawa, Performative Approaches in Art and Science Using the Example of "Performance Art" R. Koberg / Die Kunst des Gehens Mitsutaka Ishi, Testuro Tamura, Musical Performance (book) Stan Godlovitch Kunstforum Bd. 34 / Plastik als important for Patrice Pavis) Performativity and Performance (book) ! Geoffrey Leech / Principles -

ATTALAI GÁBOR Konceptuális Mûvek Conceptual Works 1969-85

ATTALAI GÁBOR Konceptuális mûvek Conceptual Works 1969-85 ATTALAI GÁBOR Konceptuális mûvek Conceptual Works 1969-85 V I N T A G E G A L É R I A BUDAP EST20 13 Fehér Dávid összeolvashatjuk Tót Endre ambivalens örömök tárgyát képező, perjelekből képzett „eső-rácsaival” is,8 melyek függönyként zár- ták el a tekintetet a távoli látványoktól – az izoláció és a „zéró információ esztétikai kérdéseivel”9 vetettek számot. Az eltűnő, lát- TRANSZFER IDEÁK hatatlan kép sokkal inkább tekinthető egy információhiányos világ sajátos dokumentumának, mint valamiféle konceptuális Megjegyzések Attalai Gábor konceptuális műveihez indíttatású intellektuális redukció végeredményének. A semmiben lógás, az akasztottság helyzete mintha indirekt módon egy régió általános életérzésére, létállapotára is utalna, akárcsak Lakner László Joseph Kosuthot idéző lelógatott üveglapja esetén, „Kimostam egy képet a keretből, de azonnal feltűnt egy másik.” melyen a felirat, „Üveglapon / lógva / árnyékot vetve”, egy fenyegető helyzetet ír le (Önleíró objekt, 1972).10 Attalai Gábor, 1970 körül A Keretéből kimosott festmény összefüggésbe hozható Attalai 1970-71-ben készült fotósorozatával. A helyszín ezúttal is a jól is- Egy tetőteraszon felállított zuhanyról egy üres képkeret lóg le. Kihasít a korlát mögött látszó hegyoldalból egy darabot – a keretbe mert tetőterasz, ahol Attalai egy kör alakú lencse segítségével megfordítja, a feje tetejére állítja a táj egy-egy részletét, legtöbb- foglalt esetleges, alkalmi tájkép a mozgásnak megfelelően folyton változik. A zuhanyrózsából kifolyó vízsugár mintha ráíródna ször közvetlen környezetének, a Gellért-hegynek emblematikus motívumait, például a Szabadság-szobrot, mely persze csupán a keret által kijelölt imaginárius képre. Attalai Gábor fényképen rögzített szegényes-eszköztelen minimál-installációja a koncep- a nevében utalt a szabadságra. -

L'internationale. Post-War Avant-Gardes Between 1957 And

EDITED BY CHRISTIAN HÖLLER A PUBLICATION OF L’INTERNATIONALE BOOKS L’INTERNATIONALE POST-WAR AVANT-GARDES BETWEEN 1957 AND 1986 EDITED BY CHRISTIAN HÖLLER TABLE OF CONTENTS 13 63 162 OPEN Approaching Art through Ensembles Should Ilya Kabakov Bart de Baere Be Awakened? 14 Viktor Misiano Museum of Parallel Narratives, 85 Museu d’Art Contemporani An Exercise in Affects 177 de Barcelona (MACBA), Barcelona (2011) Bojana Piškur Forgotten in the Folds of History Zdenka Badovinac Wim Van Mulders 95 31 What if the Universe 192 Museum of Affects, Started Here and Elsewhere Is Spain Really Different? Moderna galerija, Ljubljana (2011 / 12) Steven ten Thije Teresa Grandas Bart de Baere, Bartomeu Marí, with Leen De Backer, 106 203 Teresa Grandas and Bojana Piškur Age of Change CASE STUDIES Christian Höller 37 204 Prologue: L’Internationale 119 A. ARTISTS Zdenka Badovinac, CIRCUMSCRIBING Bart De Baere, Charles Esche, THE PERIOD 205 Bartomeu Marí and KwieKulik / Form is a Fact of Society Georg Schöllhammer 120 Georg Schöllhamer Connect Whom? Connect What? 42 Why Connect? 215 METHODOLOGY The World System after 1945 Július Koller / Dialectics Immanuel Wallerstein of Self-Identification 43 Daniel Grún Writing History Without 134 a Prior Canon Recycling the R-waste 224 Bartomeu Marí (R is for Revolution) Gorgona / Beyond Aesthetic Reality Boris Buden Branka Stipancic 52 Histories and 145 230 Their Different Art as Mousetrap: OHO / An Experimental Microcosm Narrators The Case of Laibach on the Edge of East and West Zdenka Badovinac Eda Čufer Ksenya Gurshtein -

KEN FRIEDMAN:-:-::-::-=:-:-~:-·To-Be

KEN FRIEDMAN:-:-::-::-=:-:-~:-·To-Be. by . MarDyn Ek~ ~vlcz, ~.n~. ... with a preface by Thomas Joseph Mew, m, Ph.D. KEN 1! R I E D M. A N ~:---:Th=r:e:o.....::W:;:o;::.r7-ld;-:Tb;:::a:.:t~I::s.L2 ~-- The World That Is To Be • .. : by· . :tfarilyn Ekdanl Ravie~, Pb. D. with a preface by Thomas Joseph Mewt III, Ph. D. " PREFACE Itm always tempted to refer to Ken Friedman aa "Kundalin111 Ken sinc:e I always think of him and his work as having an affinity with Kundalini, one of the most important of the Oriental doctrines. We know. for instance, that the highest ~reaktbrougbs in the West, and the recognition of a transpersonal, metapsycbological dimension have always been reaerved for our mfStics, poets, and artists. Ron Friedman, in talking about what constitutes an important work of art, speaks of it .being possessed of a telling. power,. moving •. like a snake ·.to_ ra~se. its head and s~rike ~t the right momenta · · ·.This· concept. ·~n it~elf·, is· ~ot unlike the serpent goddess of. the ~ tundalini, moving upward within the yogi's spine~ traveling along a ~e~tral channel, one known to_ be rich in ~ppiness and highly blessed• . ' Ken seems to be able, very· naturally and ·honestly, to provoke the snake and to soothe it all at once, and here a faculty of the human mind comes into play-~-a faculty Which modern man has virtually neglected or almost completely forgotten. I refer to the profound insight and forces of our' depth ~onsciousness, sueb as intuitive perception. -

Inventaire Presskit-UK-21Dec-Vf.Pdf

I�I�I�I�I�§ I�I�I�I�I�I�§ I�I�I�I�I�I�I�I�I�I� I�I�I�I�I� 26.01.2021 → 20.06.2021 I�I�I� MAMCO | Musée d’art moderne et contemporain [email protected] T + 41 22 320 61 22 10, rue des Vieux-Grenadiers | CH–1205 Genève www.mamco.ch F + 41 22 781 56 81 I�I�I�I�I�I�I�I� Introduction p. 3 Minimalism/Post-minimalism p. 4 Balthasar Burkhard/Niele Toroni p. 5 Supports/Surfaces p. 6 Archives Ecart p. 7 Robert Filliou p. 8 Nam June Paik p. 9 Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt p. 10 Body Art p. 11 Situationists Legacies p. 12 Présence Panchounette p. 13 The Street, Urban Spaces p. 14 Scheerbart Parlour p. 15 Theatricalities p. 16 The “Pictures Generation“ p. 17 Appropriation p. 18 Ericka Beckman p. 19 The Agency p. 20 Readymades p. 21 Neo-Geo and Beyond p. 22 Figurations p. 23 General Idea/Guerrilla Girls p. 24 Sylvie Fleury p. 25 Amy O’Neill p. 26 Alain Séchas p. 27 Renée Levi p. 28 Adel Abdessemed p. 29 Tatiana Trouvé p. 30 Liquid Images p. 31 Timothée Calame/Mike Lash p. 32 Moo Chew Wong p. 33 Iconography p. 34 Exhibition Partners p. 37 2 I�I�I�I�I�I�I�I�I�I�I�I� Since March 2020, the COVID-19 crisis and the measures aimed at com- bating it have profoundly affected MAMCO’s programming and opera- tions. For months, we were prevented from carrying out our main mis- sion of receiving the public. -

La Galerie | Endre Tót Endre Tót Bio Né En 1937 À

salle principale | la galerie | Endre Tót Endre Tót bio _ Né en 1937 à Sümeg (Hongrie), vit et travaille à Cologne (Allemagne) Endre Tót est l'une des figures les plus importantes de la génération néo-avant-gardiste hongroise et une figure emblématique de l’art conceptuel et du Mail art à l’échelle internationale. Tót a développé ses idées conceptuelles avec les séries de Nothingness, Joy ainsi que Rain à partir de 1971. La première manifestation du Nothingness est apparue avec l’usage du caractère Zéro qui s’inscrit sur différents supports et dans différents médias. Les soi-disant « Joys » ou « Gladnesses » de Tót étaient des parodies humoristiques de la culture de l'optimisme qui ont occupé ses séries d’actions et ses œuvres durant de très longues années. Born in 1937 in Sümeg (Hungria), lives and works in Cologne (Germany) Tót is one of the most significant figures of the Hungarian neo-avant-garde generation and an emblematic figure of international conceptualism and mail art. Tót’s developed his main subjects, Nothingness, Joy, as well as his Rain series from 1971 onwards, all significant works which are signature pieces of his conceptual ideas. The first manifestation of Nothingness as an idea in Tót’s art was the use of the Zero character, appearing in various contexts and media. Tót’s so-called 'Joys' or 'Gladnesses' were humorous parodies of the culture of optimism, articulated via a long-term series of actions and artworks. Endre Tót est représenté par la galerie Salle Principale, Paris (France). salle principale | la galerie | Endre Tót expositions / exhibitions (selection) _ 2020 / Salle Principale, Paris, France (solo) / Restons Unis Sous le soleil exactement (Salle Principale), Gallery Perrotin, Paris, France . -

Exhibition Checklist

1 AGENCY: Curated by: Kevin Concannon John Noga SEPTEMBER 19 – NOVEMBER 8 : 2008 McDonough Museum of Art Youngstown State University 525 Wick Avenue, Youngstown, Ohio ISBN 0-9727049-6-5 Front Cover The Art Guys with Todd Oldham SUITS: The Clothes Make the Man, 1998-1999 Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Photo by Mark Seliger. Courtesy of the artists. CONTENTS AGENCY: Art and Advertising SEPTEMBER 19 – NOVEMBER 8 : 2008 4 Foreword Leslie Brothers 6 AGEncY: Art and Advertising Kevin Concannon ENTRIES 24 Mark Flood Kevin Concannon 26 The Art Guys Kevin Concannon 28 Swetlana Heger Kyle Stoneman 30 Hank Willis Thomas Kyle Stoneman 32 Nicola Costantino Cristina Alexander 34 Xavier Cha Kevin Concannon 36 Institute for Infinitely Small Things Cristina Alexander 38 0100101110101101.ORG Melissa King 40 Emily Berezin Susanne Slavick Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Art, School of Art, Carnegie Mellon University 42 Adam Dant Kevin Concannon 44 Justin Lieberman Samantha Sullivan and Kevin Concannon 46 David Shapiro Kevin Concannon 48 Cliff Evans Kevin Concannon 50 Robert Wilson Kevin Concannon 52 Along the Road John Noga 62 Checklist Cristina Alexander and Donna Deluca 74 Acknowledgements John Noga and Kevin Concannon 5 FOREWORD The aesthetic dimension of human intelligence is being vigorously explored by cognitive psychologists, It is therefore within this vision for the Museum that we Agency: Art and Advertising offers viewers the opportunity to embraced Agency: Art and Advertising, promoting the consider the convergence of “high” and “low” art in the context educators, and artists. The university art museum has the unique potential to play a central role in this scholarship of two curators, Professor Kevin Concannon of its close association with advertising, a realm that subsumes exploration, and to substantially change the way the arts contribute to education and public life.