Contemporary Art on the Peripheries an Eastern European Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Új Művészet, 2003, 24

október 2019 9 ISSN 0866-2185 765 Ft 19009 9 770866 218000 október Felforgatók: Felforgatók: Schwitters, Schnabel, KirályTót, 2019 szürrealisták a Magyar Nemzeti Galériában Andalúziai kutyából nem lesz szalonna: Andalúziai nem kutyából lesz szalonna: 9 A A Hantai-siker nyomában Őszi lehalászás MűtÁRGYBEFEKTETÉSI M. NOVÁK ANDR ÁS Munkácsy Mihály-díjas festőművész, az MMA rendes tagja kiállítása KONFERENCIA 2019. OKTÓBER 2. NOVEMBER 10. 2019. november 12. P E S T I V I G A D Ó , a Magyar Művészeti Akadémia székháza, Müpa, Auditorium V. emeleti kiállítóterem Budapest V. kerület, Vigadó tér 2. www.mutargykonferencia.hu OGATÓ M SZERVEZő FőTÁ minden, ami művészet mma.hu október 2019 9 Anadalúziai kutyából nem lesz szalonna Favicc A festészet többet tud, mint a fotó Kiváló holttestek diétás menüben Klaus Littmann: For Forest – The Unending Beszélgetés Székely Annamária Attraction of Nature 28 háromdimenziós kísérleteiről 46 A szürrealista mozgalom Dalítól Magritte-ig 4 TAYLER PATRICK NICHOLAS——— MULADI BRIGITTA——— GYőRFFY LÁSZLÓ———— Absztrakt kalandok Dimenziók Felforgatók Egy siker anatómiája A tér lebontása A MAOE VI. tematikus kiállítása 48 A Hantai-szerződés hazai vonatkozásai 31 D. UDVARY IldIKÓ——— Kurt Schwitters Merz-katedrálisa 10 MÉSZÁROS FLÓRA——— LESI ZOLTÁN——— Olvasó Kék-arany ragyogások Emlékül, ismerni akaróknak Ropogós, zamatos, fanyar nyomatok Molnár László festményeiről 34 E. Csorba Csilla – Sipőcz Mariann: Arany Julian Schnabel grafikái 13 LÓSKA LAJOS——— János és a fényképezés. Országh Antal TOLNAY IMRE——— fotográfus (1821–1878) -

The Art of Performance a Critical Anthology

THE ART OF PERFORMANCE A CRITICAL ANTHOLOGY edited by GREGORY BATTCOCK AND ROBERT NICKAS /ubu editions 2010 The Art of Performance A Critical Anthology 1984 Edited By: Gregory Battcock and Robert Nickas /ubueditions ubu.com/ubu This UbuWeb Edition edited by Lucia della Paolera 2010 2 The original edition was published by E.P. DUTTON, INC. NEW YORK For G. B. Copyright @ 1984 by the Estate of Gregory Battcock and Robert Nickas All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper or broadcast. Published in the United States by E. P. Dutton, Inc., 2 Park Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10016 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 79-53323 ISBN: 0-525-48039-0 Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Toronto 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition Vito Acconci: "Notebook: On Activity and Performance." Reprinted from Art and Artists 6, no. 2 (May l97l), pp. 68-69, by permission of Art and Artists and the author. Russell Baker: "Observer: Seated One Day At the Cello." Reprinted from The New York Times, May 14, 1967, p. lOE, by permission of The New York Times. Copyright @ 1967 by The New York Times Company. -

Judit Reigl: Artist Biography by Janos Gat

Judit Reigl: Artist Biography by Janos Gat Upon seeing works from Judit Reigl’s Center of Dominance series (1958–59), the great violist, Yossi Gutmann, exclaimed, “Here is someone who paints exactly the way I play. I don’t produce the sound; the sound carries me. I don’t change the tonality; the tonality changes me.” Judit Reigl, who often applies musical terms to painting, said she could not have put it better, explaining, “Time is given to us as a present that demands equal return. When I paint, fully present in every moment, I can live every moment in the present. What I do, anyone could do, but nobody does. I turn into my own instrument. Destroying as I make, taking from what I add, I erase my traces. I intervene in order to simplify. The control I exercise in each stroke of paint is like the pianist’s when touching a key. You are one with the key, the hammer and the wire. You are in a knot with the composer and the listener, forever unraveling. The chord matches your state and the sound your existence.”1 The flux motif is paramount in the Reigl Saga. According to family lore, Reigl’s father’s ancestors were aristocratic refugees from revolutionary France, sheltered on the princely estate of Eszterháza. Her mother came from a Saxon settlement in northeastern Hungary that kept its German language and culture intact over eight centuries. At the start of World War I, Judit’s father, entombed for three days beneath the rubble of an explosion at Przemysl, miraculously rose from the dead.2 A prisoner of war in Siberia for six years after his resurrection, he escaped repeatedly and fought his way home through civil-war-torn Russia. -

Report on Futures Past Editor's Note Table of Contents

Report on the Construction of tranzit j a n 2 2 – a p r 1 3 , 2 0 1 4 a Spaceship Module new museum REPORT ON FUTURES PAST Lauren Cornell fantasies from the socialist side of the Iron tors worked on this exhibition: Vít Havránek, Director of tranzit in Prague, Dóra Curtain. As depictions of the future are always Hegyi, Director of tranzit in Budapest, and Georg Schöllhammer, Director of tranzit deeply tied to the moments in which they are in Vienna. Much like the Museum as Hub program (the New Museum’s interna- conceived, the craft also symbolizes numerous tional partnership through which the exhibition is produced), tranzit organizations realities flattened out and stitched together or actively collaborate with each other, but also work independently to produce art “come back to haunt,”1 as Philip K. Dick has historical research, exhibitions, and new commissions. The work included in this written, all within one seamless vessel. exhibition—all made by artists that tranzit has worked with in some capacity or, alternately, documentation of events or exhibitions tranzit has staged—consti- “Report on the Construction of a Spaceship tutes an “innovative archive”2 of their organization. Module” is an exhibition about art’s movement across time and space. The featured artworks, Across poetry, performative actions, diagrammatic schemas, avatars, found made by artists mainly from former Eastern objects, collections of photographs, and architectural models, “Report on the Bloc countries over the past sixty years, draw Construction of a Spaceship Module” reflects tranzit’s efforts to gather, remember, from a vast breadth of historic periods and and argue for art within Eastern Europe, and its porous connections to art outside artistic movements. -

Ecart Publications (1973-1982) Ou La Mise En Circulation De L’Art Dans Le Livre

Unicentre CH-1015 Lausanne http://serval.unil.ch 2020 Anatomie d’une imprimerie : Ecart Publications (1973-1982) ou la mise en circulation de l’art dans le livre Pierre-Paul Bianchi Pierre-Paul Bianchi, 2020, Anatomie d’une imprimerie : Ecart Publications (1973-1982) ou la mise en circulation de l’art dans le livre Originally published at : Mémoire de maîtrise, Université de Lausanne Posted at the University of Lausanne Open Archive. http://serval.unil.ch Droits d’auteur L'Université de Lausanne attire expressément l'attention des utilisateurs sur le fait que tous les documents publiés dans l'Archive SERVAL sont protégés par le droit d'auteur, conformément à la loi fédérale sur le droit d'auteur et les droits voisins (LDA). A ce titre, il est indispensable d'obtenir le consentement préalable de l'auteur et/ou de l’éditeur avant toute utilisation d'une oeuvre ou d'une partie d'une oeuvre ne relevant pas d'une utilisation à des fins personnelles au sens de la LDA (art. 19, al. 1 lettre a). A défaut, tout contrevenant s'expose aux sanctions prévues par cette loi. Nous déclinons toute responsabilité en la matière. Copyright The University of Lausanne expressly draws the attention of users to the fact that all documents published in the SERVAL Archive are protected by copyright in accordance with federal law on copyright and similar rights (LDA). Accordingly it is indispensable to obtain prior consent from the author and/or publisher before any use of a work or part of a work for purposes other than personal use within the meaning of LDA (art. -

Judit Reigl (1923-2020)

JUDIT REIGL (1923-2020) Judit Reigl was one of the few women artists to be part of the post-war action painting movement. Reigl’s work was the result of a grappling with her materials, springing from the very motion of her creative gestures, a physical energy taking place in space-time. BIOGRAPHY Simon Hantaï, Claude Georges and Claude Viseux. In the THE PAINTER JUDIT REIGL’S EARLY LIFE AND same year, she began working with the Galerie Kléber ARTISTIC TRAINING in Paris, which was directed by Jean Fournier. The gallery Born in 1923 in Kaposvár, Hungary, Judit Reigl studied at presented three solo exhibitions of Reigl’s work in 1956, the Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest between 1941 and 1959 and 1962. 1945. Thanks to a scholarship, Reigl was able to travel to Italy, where she spent nearly two years studying in Rome, JUDIT REIGL AND THE CENTRE DE DOMINANCES Venice and Verona between 1946 and 1948. After several SERIES (1958–1959) failed attempts, Reigl succeeded in fleeing Hungary but Reigl’s ongoing gestural exploration of painting led her was arrested in Austria, where she was imprisoned for a to create the series Centre de dominances [Centre of fortnight before escaping again. After a long journey— Dominance], in which her gestural marks swirled in a partly on foot—that took Reigl through Munich, Brussels rotating movement as if siphoned towards the centre of and Lille, she finally arrived in Paris in June 1950. the canvas. Describing the series, Marcelin Pleynet wrote: JUDIT REIGL AND SURREALISM (1950–1954) “On the face of the canvas, the centre presents itself as a maelstrom, abyss, vortex, delving into the depths of the In Paris, Reigl was reunited with her friend, the Hungarian work, moving and opening, forming and coming undone painter Simon Hantai, who introduced her to André while constituting itself. -

MUNICH (May, 2021) – Luxury Fashion Online Retailer Mytheresa Is

MYTHERESA PARTNERS WITH LE CENTRE POMPIDOU : WOMEN IN ABSTRACTION EXHIBITION MAY 19 - AUGUST 23, 2021 L’artiste américaine Lynda Benglis réalisant un projet commande par l’Université de Rhode Island, Kingston, Rhode Island, 1969. © Adagp, Paris 2021. Photo by Henry Groskinsky /The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images MUNICH (May, 2021) – Luxury fashion online retailer Mytheresa is honored to be a sponsor of the “Women in Abstraction” exhibition, to support and give recognition to female artists around the globe. The “Women in Abstraction” exhibition, which should be presented at the Centre Pompidou from May 19th to August 23th 2021, offers a new take on the history of abstraction - from its origins to the 1980s - and brings together the specific contributions of around one hundred and ten “women artists”. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION PLEASE CONTACT: MYTHERESA SANDRA ROMANO PHONE: +49 89 12 76 95-236 EMAIL: [email protected] MYTHERESA PARTNERS WITH LE CENTRE POMPIDOU : WOMEN IN ABSTRACTION EXHIBITION MAY 19 - AUGUST 23, 2021 “Les amis du Centre Pompidou and the Centre Pompidou express their warmest thanks to Mytheresa and to its CEO, Michael Kliger, for their so generous support and positive commitment to the pivotal Women in Abstrac- tion exhibition, which opens in May at the Centre Pompidou”, commented Floriane de Saint Pierre, Chair of the Board of the amis du Centre Pompidou and Serge Lasvignes, President of the Centre Pompidou. “We are very proud and excited to sponsor this outstanding exhibition, in the globally renowned museum such as Le Centre Pompidou. Empowering women is a mission truly close to our heart at Mytheresa and this exhibition shows the importance and impact at women's art work and gives them the recognition they deserve within the Abstract movement on a global scale”, says Michael Kliger, CEO of Mytheresa. -

JUDIT REIGL Entrance–Exit (1986-89)

JUDIT REIGL Entrance–Exit (1986-89) October 30th – December 14th, 2013 SHEPHERD W & K GALLERIES JUDIT REIGL ENTRANCE–EXIT (1986-89) October 30th through December 14th, 2013 Exhibition organized by Robert Kashey, David Wojciechowski, Alois Wienerroither and Eberhard Kohlbacher SHEPHERD W & K GALLERIES 58 East 79th Street New York, N.Y. 10075 Tel: 212 861 4050 Fax: 212 772 1314 [email protected] www.shepherdgallery.com JUDIT REIGL ENTRANCE-EXIT (1986-89) October 30th through December 14th, 2013 Shepherd W & K Galleries are proud to present an exhibition of works by Judit Reigl centered on an extraordinary series from the late 1980s, the Entrance–Exit paintings. The series, which is distinguished by the image of an open portal, is emblematic of the life and career of a fiercely independent artist who is now recognized as one of the most original painters of the late 20th century. This event coincides with our associates W & K Fine Arts’ Viennese introductory exhibition of Judit Reigl (Entrée–Sortie, October 8th through November 16th). By a quirk of fate, the artist is deeply connected to Austria. Judit Reigl was born in 1923 in Kapuvár on Hungary’s Austrian border. In 1946, on her way to Italy to study at the Hungarian Academy in Rome, Reigl spent four months in Vienna waiting for her Italian visa. Although she lacked a ration card, the opportunity to see the paintings of Bruegel, Correggio, and Rubens and to attend concerts made up for the deprivation she endured. A new world opened to her. After two years in Italy, Reigl returned home. -

FY2009 Annual Listing

2008 2009 Annual Listing Exhibitions PUBLICATIONS Acquisitions GIFTS TO THE ANNUAL FUND Membership SPECIAL PROJECTS Donors to the Collection 2008 2009 Exhibitions at MoMA Installation view of Pipilotti Rist’s Pour Your Body Out (7354 Cubic Meters) at The Museum of Modern Art, 2008. Courtesy the artist, Luhring Augustine, New York, and Hauser & Wirth Zürich London. Photo © Frederick Charles, fcharles.com Exhibitions at MoMA Book/Shelf Bernd and Hilla Becher: Home Delivery: Fabricating the Through July 7, 2008 Landscape/Typology Modern Dwelling Organized by Christophe Cherix, Through August 25, 2008 July 20–October 20, 2008 Curator, Department of Prints Organized by Peter Galassi, Chief Organized by Barry Bergdoll, The and Illustrated Books. Curator of Photography. Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture and Design, and Peter Glossolalia: Languages of Drawing Dalí: Painting and Film Christensen, Curatorial Assistant, Through July 7, 2008 Through September 15, 2008 Department of Architecture and Organized by Connie Butler, Organized by Jodi Hauptman, Design. The Robert Lehman Foundation Curator, Department of Drawings. Chief Curator of Drawings. Young Architects Program 2008 Jazz Score July 20–October 20, 2008 Multiplex: Directions in Art, Through September 17, 2008 Organized by Andres Lepik, Curator, 1970 to Now Organized by Ron Magliozzi, Department of Architecture and Through July 28, 2008 Assistant Curator, and Joshua Design. Organized by Deborah Wye, Siegel, Associate Curator, The Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Department of Film. Dreamland: Architectural Chief Curator of Prints and Experiments since the 1970s Illustrated Books. George Lois: The Esquire Covers July 23, 2008–March 16, 2009 Through March 31, 2009 Organized by Andres Lepik, Curator, Projects 87: Sigalit Landau Organized by Christian Larsen, Department of Architecture and Through July 28, 2008 Curatorial Assistant, Research Design. -

Fluxus Reader By: Ken Friedman Edited by Ken Friedman ISBN: 0471978582 See Detail of This Book on Amazon.Com

The Fluxus Reader By: Ken Friedman Edited by Ken Friedman ISBN: 0471978582 See detail of this book on Amazon.com Book served by AMAZON NOIR (www.amazon-noir.com) project by: PAOLO CIRIO paolocirio.net UBERMORGEN.COM ubermorgen.com ALESSANDRO LUDOVICO neural.it Page 1 PART I THREE HISTORIESPART I THREE HISTORIESPART I THREE HISTORIES Page 2 Page 3 Ben Patterson, Terry Reilly and Emmett Williams, of whose productions we will see this evening, pursue purposes already completely separate from Cage, though they have, however, a respectful affection.' After this introduction the concert itself began with a performance of Ben Patterson's Paper Piece. Two performers entered the stage from the wings carrying a large 3'x15' sheet of paper, which they then held over the heads of the front of the audience. At the same time, sounds of crumpling and tearing paper could be heard from behind the on-stage paper screen, in which a number of small holes began to appear. The piece of paper held over the audience's heads was then dropped as shreds and balls of paper were thrown over the screen and out into the audience. As the small holes grew larger, performers could be seen behind the screen. The initial two performers carried another large sheet out over the audience and from this a number of printed sheets of letter-sized paper were dumped onto the audience. On one side of these sheets was a kind of manifesto: "PURGE the world of bourgeois sickness, `intellectual', professional & commercialised culture, PURGE the world of dead art, imitation, artificial art, abstract art, illusionistic Page 4 [...] FUSE the cadres of cultural, social & political revolutionaries into united front & action."2 The performance of Paper Piece ended as the paper screen was gradually torn to shreds, leaving a paper-strewn stage. -

Performance Art Context R

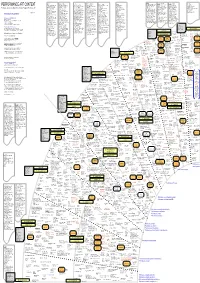

Literature: Literature: (...continued) Literature: Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Kunstf. Bd.137 / Atlas der Künstlerreisen Literature: (...continued) Literature: (... continued) Richard Kostelnatz / The Theater of Crossings (catalogue) E. Jappe / Performance Ritual Prozeß Walking through society (yearbook) ! Judith Butler !! / Bodies That Matter Victoria Best & Peter Collier (Ed.) / article: Kultur als Handlung Kunstf. Bd.136 / Ästhetik des Reisens Butoh – Die Rebellion des Körpers PERFORMANCE ART CONTEXT R. Shusterman / Kunst leben – Die Ästhetik Mixed Means. An Introduction to Zeitspielräume. Performance Musik On Ritual (Performance Research) Eugenio Barber (anthropological view) Performative Acts and Gender Constitution Powerful Bodies – Performance in French Gertrude Koch Zeit – Die vierte Dimension in der (Kazuo Ohno, Carlotta Ikeda, Tatsumi des Pragmatismus Happenings, Kinetic Environments ... ! Ästhetik / Daniel Charles Richard Schechner / Future of Ritual Camille Camillieri (athropolog. view; (article 1988!) / Judith Butler Cultural Studies !! Mieke Bal (lecture) / Performance and Mary Ann Doane / Film and the bildenden Kunst Hijikata, Min Tanaka, Anzu Furukawa, Performative Approaches in Art and Science Using the Example of "Performance Art" R. Koberg / Die Kunst des Gehens Mitsutaka Ishi, Testuro Tamura, Musical Performance (book) Stan Godlovitch Kunstforum Bd. 34 / Plastik als important for Patrice Pavis) Performativity and Performance (book) ! Geoffrey Leech / Principles -

ATTALAI GÁBOR Konceptuális Mûvek Conceptual Works 1969-85

ATTALAI GÁBOR Konceptuális mûvek Conceptual Works 1969-85 ATTALAI GÁBOR Konceptuális mûvek Conceptual Works 1969-85 V I N T A G E G A L É R I A BUDAP EST20 13 Fehér Dávid összeolvashatjuk Tót Endre ambivalens örömök tárgyát képező, perjelekből képzett „eső-rácsaival” is,8 melyek függönyként zár- ták el a tekintetet a távoli látványoktól – az izoláció és a „zéró információ esztétikai kérdéseivel”9 vetettek számot. Az eltűnő, lát- TRANSZFER IDEÁK hatatlan kép sokkal inkább tekinthető egy információhiányos világ sajátos dokumentumának, mint valamiféle konceptuális Megjegyzések Attalai Gábor konceptuális műveihez indíttatású intellektuális redukció végeredményének. A semmiben lógás, az akasztottság helyzete mintha indirekt módon egy régió általános életérzésére, létállapotára is utalna, akárcsak Lakner László Joseph Kosuthot idéző lelógatott üveglapja esetén, „Kimostam egy képet a keretből, de azonnal feltűnt egy másik.” melyen a felirat, „Üveglapon / lógva / árnyékot vetve”, egy fenyegető helyzetet ír le (Önleíró objekt, 1972).10 Attalai Gábor, 1970 körül A Keretéből kimosott festmény összefüggésbe hozható Attalai 1970-71-ben készült fotósorozatával. A helyszín ezúttal is a jól is- Egy tetőteraszon felállított zuhanyról egy üres képkeret lóg le. Kihasít a korlát mögött látszó hegyoldalból egy darabot – a keretbe mert tetőterasz, ahol Attalai egy kör alakú lencse segítségével megfordítja, a feje tetejére állítja a táj egy-egy részletét, legtöbb- foglalt esetleges, alkalmi tájkép a mozgásnak megfelelően folyton változik. A zuhanyrózsából kifolyó vízsugár mintha ráíródna ször közvetlen környezetének, a Gellért-hegynek emblematikus motívumait, például a Szabadság-szobrot, mely persze csupán a keret által kijelölt imaginárius képre. Attalai Gábor fényképen rögzített szegényes-eszköztelen minimál-installációja a koncep- a nevében utalt a szabadságra.