KEN FRIEDMAN:-:-::-::-=:-:-~:-·To-Be

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Új Művészet, 2003, 24

október 2019 9 ISSN 0866-2185 765 Ft 19009 9 770866 218000 október Felforgatók: Felforgatók: Schwitters, Schnabel, KirályTót, 2019 szürrealisták a Magyar Nemzeti Galériában Andalúziai kutyából nem lesz szalonna: Andalúziai nem kutyából lesz szalonna: 9 A A Hantai-siker nyomában Őszi lehalászás MűtÁRGYBEFEKTETÉSI M. NOVÁK ANDR ÁS Munkácsy Mihály-díjas festőművész, az MMA rendes tagja kiállítása KONFERENCIA 2019. OKTÓBER 2. NOVEMBER 10. 2019. november 12. P E S T I V I G A D Ó , a Magyar Művészeti Akadémia székháza, Müpa, Auditorium V. emeleti kiállítóterem Budapest V. kerület, Vigadó tér 2. www.mutargykonferencia.hu OGATÓ M SZERVEZő FőTÁ minden, ami művészet mma.hu október 2019 9 Anadalúziai kutyából nem lesz szalonna Favicc A festészet többet tud, mint a fotó Kiváló holttestek diétás menüben Klaus Littmann: For Forest – The Unending Beszélgetés Székely Annamária Attraction of Nature 28 háromdimenziós kísérleteiről 46 A szürrealista mozgalom Dalítól Magritte-ig 4 TAYLER PATRICK NICHOLAS——— MULADI BRIGITTA——— GYőRFFY LÁSZLÓ———— Absztrakt kalandok Dimenziók Felforgatók Egy siker anatómiája A tér lebontása A MAOE VI. tematikus kiállítása 48 A Hantai-szerződés hazai vonatkozásai 31 D. UDVARY IldIKÓ——— Kurt Schwitters Merz-katedrálisa 10 MÉSZÁROS FLÓRA——— LESI ZOLTÁN——— Olvasó Kék-arany ragyogások Emlékül, ismerni akaróknak Ropogós, zamatos, fanyar nyomatok Molnár László festményeiről 34 E. Csorba Csilla – Sipőcz Mariann: Arany Julian Schnabel grafikái 13 LÓSKA LAJOS——— János és a fényképezés. Országh Antal TOLNAY IMRE——— fotográfus (1821–1878) -

Major Exhibition Poses Tough Questions and Reasserts Fluxus Attitude

Contact: Alyson Cluck 212/998-6782 or [email protected] Major Exhibition Poses Tough Questions And Reasserts Fluxus Attitude Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life and Fluxus at NYU: Before and Beyond open at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery on September 9, 2011 New York City (July 21, 2011)—On view from September 9 through December 3, 2011, at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery, Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life features over 100 works dating primarily from the 1960s and ’70s by artists such as George Brecht, Robert Filliou, Ken Friedman, George Maciunas, Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, Mieko Shiomi, Ben Vautier, and La Monte Young. Curated by art historian Jacquelynn Baas and organized by Dartmouth College’s Hood Museum of Art, the exhibition draws heavily on the Hood’s George Maciunas Memorial Collection, and includes art objects, documents, videos, event scores, and Fluxkits. Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life is accompanied by a second installation, Fluxus at NYU: Before and Beyond, in the Grey’s Lower Level Gallery. Fluxus—which began in the 1960s as an international network of artists, composers, and designers―resists categorization as an art movement, collective, or group. It also defies traditional geographical, chronological, and medium-based approaches. Instead, Fluxus participants employ a “do-it-yourself” attitude, relating their activities to everyday life and to viewers’ experiences, often blurring the boundaries between art and life. Offering a fresh look at Fluxus, the show and its installation are George Maciunas, Burglary Fluxkit, 1971. Hood designed to spark multiple interpretations, exploring Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, George Maciunas Memorial Collection: Gift of the Friedman Family; the works’ relationships to key themes of human GM.986.80.164. -

Ken Friedman: 92 Events 02.06.20 – 16.08.20 the Distance from the Sentence to Your Eyes Is My Sculpture

Ken Friedman: 92 Events 02.06.20 – 16.08.20 The distance from the sentence to your eyes is my sculpture. Ken Friedman 92 Events presents works spanning six decades by American-born Swedish Fluxus artist Ken Friedman. Friedman produces conceptual, action-oriented, language-based works that attach themselves to daily life and challenge the idea of an artwork as a unique object. This exhibition was conceived by the artist and Copenhagen- based art historian Peter van der Meijden. Adam Art Gallery is the first venue for this project. The exhibition will tour globally over the coming years. Ken Friedman joined Fluxus in 1966 as the youngest member, invited by George Maciunas, co-founder of the international group. In the ten years before joining Fluxus, Friedman did not call these works ‘art’. It was with the encouragement of Maciunas that Friedman began to notate his works as scores. The earliest scores in this series are dated with the year he conceived the idea. Friedman conceived the first work in 1956, when he was six. It encourages readers to ‘Go to a public monument on the first day of spring’ to clean it thoroughly without any public announcement. Friedman’s playful and idiosyncratic approach has remained remarkably consistent. The most recent work in the series, written in 2019, presciently posits the idea of an exhibition which is closed and locked for the duration of its presentation, with a sign announcing: ‘There is a wonderful exhibition inside. You are not allowed to see it’. For Friedman, the conditions of the exhibition are as important as what we might think of as the work itself. -

The Art of Performance a Critical Anthology

THE ART OF PERFORMANCE A CRITICAL ANTHOLOGY edited by GREGORY BATTCOCK AND ROBERT NICKAS /ubu editions 2010 The Art of Performance A Critical Anthology 1984 Edited By: Gregory Battcock and Robert Nickas /ubueditions ubu.com/ubu This UbuWeb Edition edited by Lucia della Paolera 2010 2 The original edition was published by E.P. DUTTON, INC. NEW YORK For G. B. Copyright @ 1984 by the Estate of Gregory Battcock and Robert Nickas All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper or broadcast. Published in the United States by E. P. Dutton, Inc., 2 Park Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10016 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 79-53323 ISBN: 0-525-48039-0 Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Toronto 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition Vito Acconci: "Notebook: On Activity and Performance." Reprinted from Art and Artists 6, no. 2 (May l97l), pp. 68-69, by permission of Art and Artists and the author. Russell Baker: "Observer: Seated One Day At the Cello." Reprinted from The New York Times, May 14, 1967, p. lOE, by permission of The New York Times. Copyright @ 1967 by The New York Times Company. -

Fluxus: the Is Gnificant Role of Female Artists Megan Butcher

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College Summer 7-2018 Fluxus: The iS gnificant Role of Female Artists Megan Butcher Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Contemporary Art Commons, and the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Butcher, Megan, "Fluxus: The iS gnificant Role of Female Artists" (2018). Honors College Theses. 178. https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/178 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pforzheimer Honors College at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract The Fluxus movement of the 1960s and early 1970s laid the groundwork for future female artists and performance art as a medium. However, throughout my research, I have found that while there is evidence that female artists played an important role in this art movement, they were often not written about or credited for their contributions. Literature on the subject is also quite limited. Many books and journals only mention the more prominent female artists of Fluxus, leaving the lesser-known female artists difficult to research. The lack of scholarly discussion has led to the inaccurate documentation of the development of Fluxus art and how it influenced later movements. Additionally, the absence of research suggests that female artists’ work was less important and, consequently, keeps their efforts and achievements unknown. It can be demonstrated that works of art created by little-known female artists later influenced more prominent artists, but the original works have gone unacknowledged. -

Report on Futures Past Editor's Note Table of Contents

Report on the Construction of tranzit j a n 2 2 – a p r 1 3 , 2 0 1 4 a Spaceship Module new museum REPORT ON FUTURES PAST Lauren Cornell fantasies from the socialist side of the Iron tors worked on this exhibition: Vít Havránek, Director of tranzit in Prague, Dóra Curtain. As depictions of the future are always Hegyi, Director of tranzit in Budapest, and Georg Schöllhammer, Director of tranzit deeply tied to the moments in which they are in Vienna. Much like the Museum as Hub program (the New Museum’s interna- conceived, the craft also symbolizes numerous tional partnership through which the exhibition is produced), tranzit organizations realities flattened out and stitched together or actively collaborate with each other, but also work independently to produce art “come back to haunt,”1 as Philip K. Dick has historical research, exhibitions, and new commissions. The work included in this written, all within one seamless vessel. exhibition—all made by artists that tranzit has worked with in some capacity or, alternately, documentation of events or exhibitions tranzit has staged—consti- “Report on the Construction of a Spaceship tutes an “innovative archive”2 of their organization. Module” is an exhibition about art’s movement across time and space. The featured artworks, Across poetry, performative actions, diagrammatic schemas, avatars, found made by artists mainly from former Eastern objects, collections of photographs, and architectural models, “Report on the Bloc countries over the past sixty years, draw Construction of a Spaceship Module” reflects tranzit’s efforts to gather, remember, from a vast breadth of historic periods and and argue for art within Eastern Europe, and its porous connections to art outside artistic movements. -

Ecart Publications (1973-1982) Ou La Mise En Circulation De L’Art Dans Le Livre

Unicentre CH-1015 Lausanne http://serval.unil.ch 2020 Anatomie d’une imprimerie : Ecart Publications (1973-1982) ou la mise en circulation de l’art dans le livre Pierre-Paul Bianchi Pierre-Paul Bianchi, 2020, Anatomie d’une imprimerie : Ecart Publications (1973-1982) ou la mise en circulation de l’art dans le livre Originally published at : Mémoire de maîtrise, Université de Lausanne Posted at the University of Lausanne Open Archive. http://serval.unil.ch Droits d’auteur L'Université de Lausanne attire expressément l'attention des utilisateurs sur le fait que tous les documents publiés dans l'Archive SERVAL sont protégés par le droit d'auteur, conformément à la loi fédérale sur le droit d'auteur et les droits voisins (LDA). A ce titre, il est indispensable d'obtenir le consentement préalable de l'auteur et/ou de l’éditeur avant toute utilisation d'une oeuvre ou d'une partie d'une oeuvre ne relevant pas d'une utilisation à des fins personnelles au sens de la LDA (art. 19, al. 1 lettre a). A défaut, tout contrevenant s'expose aux sanctions prévues par cette loi. Nous déclinons toute responsabilité en la matière. Copyright The University of Lausanne expressly draws the attention of users to the fact that all documents published in the SERVAL Archive are protected by copyright in accordance with federal law on copyright and similar rights (LDA). Accordingly it is indispensable to obtain prior consent from the author and/or publisher before any use of a work or part of a work for purposes other than personal use within the meaning of LDA (art. -

Red Fox Press and Post-Fluxus Artistic Practices Research Thesis

A Post-Fluxus Island: Red Fox Press and Post-Fluxus Artistic Practices Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with research distinction in Comparative Studies in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Elliott Jenkins The Ohio State University April 2016 Project Advisor: Philip Armstrong, Department of Comparative Studies Second Advisor: Kris Paulsen, Department of History of Art 2 Abstract The Fluxus paradigm, which took shape in the 1960s, is a movement that was founded on an experimental artistic lifestyle. Artists sought to synthesize art and life and emphasized intermedia artistic practices that subverted the mainstream art world through creating art that was simple, playful, and sometimes created by chance. Fluxus has become an extremely enigmatic artistic movement over time and has caused some scholars to concretize it and drain its life force. Other artists and scholars believe that Fluxus is still fully alive today - just iterated in a different form. This is the crux of Fluxus thought: is it ever changing and constantly adapting to contemporary culture. While I do not contend that this key characteristic is false, I assert that the key aspects of Fluxus ideologies in the twenty-first century can also open up new avenues of interpretation. I also wish to introduce the idea that Fluxus has inspired a relatively new artistic practice - a “post-Fluxus” practice. Francis Van Maele, Antic-Ham, and their Red Fox Press are the epitome of this “post- Fluxus” mode of artistic practice. For Franticham, Fluxus is a touchstone for many of their publications. But they also go beyond that paradigm with their use of contemporary technology, the way in which they craft their global artistic community, and the way they view their place in the complex history of art. -

Fluxus Reader By: Ken Friedman Edited by Ken Friedman ISBN: 0471978582 See Detail of This Book on Amazon.Com

The Fluxus Reader By: Ken Friedman Edited by Ken Friedman ISBN: 0471978582 See detail of this book on Amazon.com Book served by AMAZON NOIR (www.amazon-noir.com) project by: PAOLO CIRIO paolocirio.net UBERMORGEN.COM ubermorgen.com ALESSANDRO LUDOVICO neural.it Page 1 PART I THREE HISTORIESPART I THREE HISTORIESPART I THREE HISTORIES Page 2 Page 3 Ben Patterson, Terry Reilly and Emmett Williams, of whose productions we will see this evening, pursue purposes already completely separate from Cage, though they have, however, a respectful affection.' After this introduction the concert itself began with a performance of Ben Patterson's Paper Piece. Two performers entered the stage from the wings carrying a large 3'x15' sheet of paper, which they then held over the heads of the front of the audience. At the same time, sounds of crumpling and tearing paper could be heard from behind the on-stage paper screen, in which a number of small holes began to appear. The piece of paper held over the audience's heads was then dropped as shreds and balls of paper were thrown over the screen and out into the audience. As the small holes grew larger, performers could be seen behind the screen. The initial two performers carried another large sheet out over the audience and from this a number of printed sheets of letter-sized paper were dumped onto the audience. On one side of these sheets was a kind of manifesto: "PURGE the world of bourgeois sickness, `intellectual', professional & commercialised culture, PURGE the world of dead art, imitation, artificial art, abstract art, illusionistic Page 4 [...] FUSE the cadres of cultural, social & political revolutionaries into united front & action."2 The performance of Paper Piece ended as the paper screen was gradually torn to shreds, leaving a paper-strewn stage. -

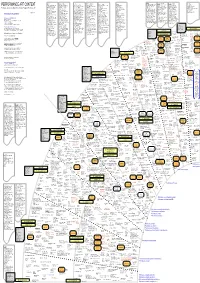

Performance Art Context R

Literature: Literature: (...continued) Literature: Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Kunstf. Bd.137 / Atlas der Künstlerreisen Literature: (...continued) Literature: (... continued) Richard Kostelnatz / The Theater of Crossings (catalogue) E. Jappe / Performance Ritual Prozeß Walking through society (yearbook) ! Judith Butler !! / Bodies That Matter Victoria Best & Peter Collier (Ed.) / article: Kultur als Handlung Kunstf. Bd.136 / Ästhetik des Reisens Butoh – Die Rebellion des Körpers PERFORMANCE ART CONTEXT R. Shusterman / Kunst leben – Die Ästhetik Mixed Means. An Introduction to Zeitspielräume. Performance Musik On Ritual (Performance Research) Eugenio Barber (anthropological view) Performative Acts and Gender Constitution Powerful Bodies – Performance in French Gertrude Koch Zeit – Die vierte Dimension in der (Kazuo Ohno, Carlotta Ikeda, Tatsumi des Pragmatismus Happenings, Kinetic Environments ... ! Ästhetik / Daniel Charles Richard Schechner / Future of Ritual Camille Camillieri (athropolog. view; (article 1988!) / Judith Butler Cultural Studies !! Mieke Bal (lecture) / Performance and Mary Ann Doane / Film and the bildenden Kunst Hijikata, Min Tanaka, Anzu Furukawa, Performative Approaches in Art and Science Using the Example of "Performance Art" R. Koberg / Die Kunst des Gehens Mitsutaka Ishi, Testuro Tamura, Musical Performance (book) Stan Godlovitch Kunstforum Bd. 34 / Plastik als important for Patrice Pavis) Performativity and Performance (book) ! Geoffrey Leech / Principles -

Getting Into Events by Ken Friedman Over the Years Since 1962, Many

Getting into Events by Ken Friedman Over the years since 1962, many event scores have been published under the aegis of Fluxus. The scores have appeared in boxes and multiple editions, on cards, in books and catalogues, and in several other forms. Several of us have presented our scores as exhibitions, on paper as drawings, calligraphy or prints, and on canvas as silk‐screens or paintings. The event scores of the artists associated with Fluxus have never been available in the single, encyclopedic compilation that George Maciunas envisioned. George announced on any number of occasions grand plans to publish 'the complete works' or 'the collected works' of Fluxus artists, La Monte Young, Emmett Williams and Jackson Mac Low among them. His failure to do so ‐‐ or their unwillingness to permit George sole authority over their work under the Fluxus aegis, led to some of the fractures within Fluxus. Other plans to publish major selections of work never came to fruition. This led in Dick Higgins' case to the publication of Postface/Jefferson's Birthday, and to the establishment of the legendary Something Else Press (and yet another schism in Fluxus). In my case, it led to a series of carbon‐ copy, xerox and mimeograph editions of my events and scores during the 60s, while waiting for George, and by the end of the 60s, to exhibitions and publications of the scores in the many different forms and contexts in which they have been seen since. )I was always careful to copyright them to Fluxus while waiting for George to finish the boxed Fluxus edition, which, as with so many of George's wonderful plans, remained unfinished.) George did realize boxed editions of many important suites of event scores.The Magna Carta of boxed event structures was surely George Brecht's WaterYam, a quintessential Fluxus edition. -

MAIL ART H/STORY^Thefluxljs by Ken Friedman

Oisteanu, Valery: Illegal Mail Art (a poetical essay), in: Mail Art Then and Now, The Flue, Vol. 4, No. 3-4 (special issue), 1984 Winter, pp. 11-12. MAIL ART H/STORY^THEFLUXlJS Downloaded from http://artpool.hu/MailArt/chrono/1984/FluxusFactor.html snared works of Arman and Spoerri, the by Ken Friedman decollages of Hains and Dufrene and the world-embracing, massively realized projects of Christo. The issues and ideas that motivated La Bertesca FLUX the Nouveaux Realistes also emerged in via del Carmine the Pop Art of the late '50's and early 20121 M ilano POST telefono 87.4J.13 | '60's in Britain and the United States, CARD PARTIAL PROGRAM : G. Brecht (Ladder, Chair, A Play. Lamp) Robert t ser (Pat’ s Birthday) Earle Joseph Byrd (Birds) John Cage (h'33” ) Barney Childs (Fourth String Quartet) P h ilip Corner Lucia Olugot iwski Robert FI 11 too (111 I' trade Mo. I - a 53 kg. poem) Malcolm though Pop Art tended to be an art Goldstein Rad Grcxmu/Rudolph Burckhardt {Shoot the Moor) Al Hanse Dick Higgins (Oanger Musi s tla ls . Two fo r Hemi Bay) Spencer lay) J ill Johnston Brooklyn Joe Jones J Holst (Stories) Terry Jennings (Piece fo r String Quartet) Ray \n which took the real into its scope (Mechanical Music) Alison Knowles (Proposition, Nlvea Cream Piece for Oscei ! Child Art) Arthur Kdpcke (music while you work) Tekenhlsa Kosugl (Micro I, An lea 1) P hilip Kruam (Construction fo r Perfoi y Kuehn Peter Longezo (A Method fo r Reversing the Direction of Rotation of the Planets) George Meciunas (Place for ___ ___ , ___ ,0r Everyman, Plano Compositions) Jackson Mac Low emblematically rather than by direct (John Bull Pack; Night Walk; Adams County, Illin o is ; Poert-au-l ice; Sth Light Poem; Solo Readings) Robert Morris (Stories, Construction) Robin Page (Soto fo r Guitar) Ben Patterson (Pond, Paper Pl< Gloves, from Methods t Processes; Three movements fo r seeing - Can you incorporation or manipulation.