And Their Relation to Historical Fluxus Opens an Essay That Examines Current Fluxus-Based Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Healthcare Riskops Manifesto

The Healthcare RiskOps Manifesto “Committees are, by nature, timid. They are based on the premise of safety in numbers; content to survive inconspicuously, rather than take risks and move independently ahead. Without independence, without the freedom for new ideas to be tried, to fail, and to ultimately succeed, the world will not move ahead, but rather live in fear of its own potential” Ferdinand Porsche And you may ask yourself, "How do I work this?" And you may ask yourself, "Where is that large automobile?" And you may tell yourself, "This is not my beautiful house." And you may tell yourself, "This is not my beautiful wife." David Byrne The End is Near “People of Earth, hear this!” A specter is haunting healthcare. And we’ve got work to do. It’s about challenging the old assumptions of managing risk because nothing has changed. Yet, everything has changed. It’s about heralding a new vision because the old one doesn’t work. Change creates opportunities. Change drives outcomes. And healthcare needs secure outcomes. Healthcare risk needs change. We must challenge assumptions: identity, role, purpose, place, power. Change built on strong beliefs that will upset the status quo. We don’t care. We are focused on moving the industry forward. Le risque est avant-gardiste. Futurism. Vorticism. Dada. Surrealism. Situationism. Neoism. Risk the Elephant. Uncaged. Risk is Nazaré. It’s a red balloon. Risk is sunflower fields. And fire on the mountain. Risk guides the first decision. It’s as old as Eden. Fight. Or flight. Risk is nucleotide. To ego. -

Major Exhibition Poses Tough Questions and Reasserts Fluxus Attitude

Contact: Alyson Cluck 212/998-6782 or [email protected] Major Exhibition Poses Tough Questions And Reasserts Fluxus Attitude Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life and Fluxus at NYU: Before and Beyond open at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery on September 9, 2011 New York City (July 21, 2011)—On view from September 9 through December 3, 2011, at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery, Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life features over 100 works dating primarily from the 1960s and ’70s by artists such as George Brecht, Robert Filliou, Ken Friedman, George Maciunas, Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, Mieko Shiomi, Ben Vautier, and La Monte Young. Curated by art historian Jacquelynn Baas and organized by Dartmouth College’s Hood Museum of Art, the exhibition draws heavily on the Hood’s George Maciunas Memorial Collection, and includes art objects, documents, videos, event scores, and Fluxkits. Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life is accompanied by a second installation, Fluxus at NYU: Before and Beyond, in the Grey’s Lower Level Gallery. Fluxus—which began in the 1960s as an international network of artists, composers, and designers―resists categorization as an art movement, collective, or group. It also defies traditional geographical, chronological, and medium-based approaches. Instead, Fluxus participants employ a “do-it-yourself” attitude, relating their activities to everyday life and to viewers’ experiences, often blurring the boundaries between art and life. Offering a fresh look at Fluxus, the show and its installation are George Maciunas, Burglary Fluxkit, 1971. Hood designed to spark multiple interpretations, exploring Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, George Maciunas Memorial Collection: Gift of the Friedman Family; the works’ relationships to key themes of human GM.986.80.164. -

Agregue Y Devuelva, MAIL ART En Las Colección Del MIDE-CIANT/UCLM

AGREGUE Y DEVUELVA MAIL ART en las colecciones del MIDE-CIANT/UCLM © de los textos e ilustraciones: sus autores. © de la edición: Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha. Textos de: José Emilio Antón, Ibírico, Ana Navarrete Tudela, Sylvia Ramírez Monroy, César Reglero y Pere Sousa. Edita: Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, MIDE-CIANT y Fundación Antonio Pérez. Colección CALEIDOSCOPIO n.º 17. Serie Cuadernos del Media Art. Dir.: Ana Navarrete Tudela Equipo de documentación: Ana Alarcón Vieco, Roberto J. Alcalde López y Clara Rodrigo Rodríguez. Fotografías: Montserrat de Pablo Moya Corrección de textos: Antonio Fernández Vicente I.S.B.N.: 978-84-9044-421-4 (Edición impresa) I.S.B.N.: 978-84-9044-422-1 (Edición electrónica) Doi: http://doi.org/10.18239/caleidos_2021.17.00 D.L.: CU 11-2021 Esta editorial es miembro de la UNE, lo que garantiza la difusión y comercialización de sus publicaciones a nivel nacional e internacional. Diseño y maquetación: CIDI (UCLM) Impresión: Trisorgar Artes Gráficas Hecho en España (U.E.) – Made in Spain (E.U.) Esta obra se encuentra bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons CC BY 4.0. Cualquier forma de reproducción, distribución, comunicación pública o transformación de esta obra no incluida en la licencia Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 solo puede ser realizada con la autorización expresa de los titulares, salvo excepción prevista por la ley. Puede Vd. acceder al texto completo de la licencia en este enlace: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.es EXPOSICIONES: Comisariado: Patricia Aragón Martín, Ana Navarrete Tudela, Montserrat de Pablo Moya Coordinación: Ana Navarrete Tudela Ayudantes de coordinación: Adoración Saiz Cañas, Ana Alarcón Vieco, Ignacio Page Valero Dirección de montaje: MIDE-CIANT/UCLM, Fundación Antonio Pérez, ArteTinta Digitalización: Ana Alarcón Vieco, Patricia Aragón y Clara Rodrigo Rodríguez Montaje y transporte: ArteTinta Centros: Sala ACUA, Cuenca. -

Ken Friedman: 92 Events 02.06.20 – 16.08.20 the Distance from the Sentence to Your Eyes Is My Sculpture

Ken Friedman: 92 Events 02.06.20 – 16.08.20 The distance from the sentence to your eyes is my sculpture. Ken Friedman 92 Events presents works spanning six decades by American-born Swedish Fluxus artist Ken Friedman. Friedman produces conceptual, action-oriented, language-based works that attach themselves to daily life and challenge the idea of an artwork as a unique object. This exhibition was conceived by the artist and Copenhagen- based art historian Peter van der Meijden. Adam Art Gallery is the first venue for this project. The exhibition will tour globally over the coming years. Ken Friedman joined Fluxus in 1966 as the youngest member, invited by George Maciunas, co-founder of the international group. In the ten years before joining Fluxus, Friedman did not call these works ‘art’. It was with the encouragement of Maciunas that Friedman began to notate his works as scores. The earliest scores in this series are dated with the year he conceived the idea. Friedman conceived the first work in 1956, when he was six. It encourages readers to ‘Go to a public monument on the first day of spring’ to clean it thoroughly without any public announcement. Friedman’s playful and idiosyncratic approach has remained remarkably consistent. The most recent work in the series, written in 2019, presciently posits the idea of an exhibition which is closed and locked for the duration of its presentation, with a sign announcing: ‘There is a wonderful exhibition inside. You are not allowed to see it’. For Friedman, the conditions of the exhibition are as important as what we might think of as the work itself. -

Real.Izing the Utopian Longing of Experimental Poetry

REAL.IZING THE UTOPIAN LONGING OF EXPERIMENTAL POETRY by Justin Katko Printed version bound in an edition of 20 @ Critical Documents 112 North College #4 Oxford, Ohio 45056 USA http://plantarchy.us REEL EYE SING THO YOU DOH PEON LAWN INC O V.EXPER(T?) I MEANT ALL POET RE: Submitted to the School of Interdisciplinary Studies (Western College Program) in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy Interdisciplinary Studies by Justin Katko Miami University Oxford, Ohio April 10, 2006 APPROVED Advisor: _________________ Xiuwu Liu ABSTRACT Capitalist social structure obstructs the potentials of radical subjectivities by over-determining life as a hierarchy of discrete labors. Structural analyses of grammatical syntax reveal the reproduction of capitalist social structure within linguistic structure. Consider how the struggle of articulation is the struggle to make language work.* Assuming an analog mesh between social and docu-textual structures, certain experimental poetries can be read as fractal imaginations of anarcho-Marxist utopianism in their fierce disruption of linguistic convention. An experimental poetry of radical political efficacy must be instantiated by and within micro-social structures negotiated by practically critical attentions to the material conditions of the social web that upholds the writing, starting with writing’s primary dispersion into the social—publishing. There are recent historical moments where such demands were being put into practice. This is a critical supplement to the first issue of Plantarchy, a hand-bound journal of contemporary experimental poetry by American, British, and Canadian practitioners. * Language work you. iii ...as an object of hatred, as the personification of Capital, as the font of the Spectacle. -

Neoist Interruptus and the Collapse of Originality

Neoist Interruptus and the Collapse of Originality Stephen Perkins 2005 Presented at the Collage As Cultural Practice Conference, University of Iowa, March 26th, Iowa City Tracing the etymology of the word collage and its compound colle becomes a fascinating journey that branches out into a number of different directions all emanating from the act of gluing things together. After reading a number of definitions that detail such activities as sticking, gluing, pasting, adhering, and the utilization of substances such as gum (British), rubber cement (US) and fish glue, one comes upon another meaning of a rather different order. In France collage has a colloquial usage to describe having an affair, and colle more specifically means to live together or to shack up together.1 While I lay no great claims to any expertise in the area of linguistic history, I would suggest that this vernacular meaning of colle arises when living together would have generated far more excitement than the term, and the activity, generates today. And, while the dictionary definition of the word does not support the interpretation that I am going to suggest here, I would argue that its usage in its original context would have generated a very particular kind of frisson that would have been implicitly associated with the act of two people being collaged or glued together, in other words fucking, or to fuck, or simply fuck. What has this to do with a paper on collage as cultural intervention, you might ask? It’s simple really, well relatively. My subject is a late 20th century international avant-garde movement known as the Neoist Cultural Conspiracy (Neoism for short), which I would argue is the last of the historic avant-gardes of the 20th century. -

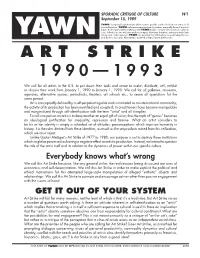

Artists in the U.S

SPORADIC CRITIQUE OF CULTURE Nº1 September 15, 1989 YAWN is a sporadic communiqué which seeks to provide a critical look at our culture in all its manifestations. YAWN welcomes responses from its readers, especially those of a critical nature. Be forewarned that anything sent to YAWN may be considered for inclusion in a future issue. Submissions are welcome and encouraged. Monetary donations are requested to help defray costs. Subscriptions to YAWN are available for $10 (cash or unused stamps) for one YAWN year by first class mail. All content is archived at http://yawn.detritus.net/. A R T S T R I K E 1 9 9 0 — 1 9 9 3 We call for all artists in the U.S. to put down their tools and cease to make, distribute, sell, exhibit or discuss their work from January 1, 1990 to January 1, 1993. We call for all galleries, museums, agencies, alternative spaces, periodicals, theaters, art schools etc., to cease all operations for the same period. Art is conceptually defined by a self-perpetuating elite and is marketed as an international commodity; the activity of its production has been mystified and co-opted; its practitioners have become manipulable and marginalized through self-identification with the term “artist” and all it implies. To call one person an artist is to deny another an equal gift of vision; thus the myth of “genius” becomes an ideological justification for inequality, repression and famine. What an artist considers to be his or her identity is simply a schooled set of attitudes; preconceptions which imprison humanity in history. -

Fluxus: the Is Gnificant Role of Female Artists Megan Butcher

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College Summer 7-2018 Fluxus: The iS gnificant Role of Female Artists Megan Butcher Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Contemporary Art Commons, and the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Butcher, Megan, "Fluxus: The iS gnificant Role of Female Artists" (2018). Honors College Theses. 178. https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/178 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pforzheimer Honors College at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract The Fluxus movement of the 1960s and early 1970s laid the groundwork for future female artists and performance art as a medium. However, throughout my research, I have found that while there is evidence that female artists played an important role in this art movement, they were often not written about or credited for their contributions. Literature on the subject is also quite limited. Many books and journals only mention the more prominent female artists of Fluxus, leaving the lesser-known female artists difficult to research. The lack of scholarly discussion has led to the inaccurate documentation of the development of Fluxus art and how it influenced later movements. Additionally, the absence of research suggests that female artists’ work was less important and, consequently, keeps their efforts and achievements unknown. It can be demonstrated that works of art created by little-known female artists later influenced more prominent artists, but the original works have gone unacknowledged. -

Red Fox Press and Post-Fluxus Artistic Practices Research Thesis

A Post-Fluxus Island: Red Fox Press and Post-Fluxus Artistic Practices Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with research distinction in Comparative Studies in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Elliott Jenkins The Ohio State University April 2016 Project Advisor: Philip Armstrong, Department of Comparative Studies Second Advisor: Kris Paulsen, Department of History of Art 2 Abstract The Fluxus paradigm, which took shape in the 1960s, is a movement that was founded on an experimental artistic lifestyle. Artists sought to synthesize art and life and emphasized intermedia artistic practices that subverted the mainstream art world through creating art that was simple, playful, and sometimes created by chance. Fluxus has become an extremely enigmatic artistic movement over time and has caused some scholars to concretize it and drain its life force. Other artists and scholars believe that Fluxus is still fully alive today - just iterated in a different form. This is the crux of Fluxus thought: is it ever changing and constantly adapting to contemporary culture. While I do not contend that this key characteristic is false, I assert that the key aspects of Fluxus ideologies in the twenty-first century can also open up new avenues of interpretation. I also wish to introduce the idea that Fluxus has inspired a relatively new artistic practice - a “post-Fluxus” practice. Francis Van Maele, Antic-Ham, and their Red Fox Press are the epitome of this “post- Fluxus” mode of artistic practice. For Franticham, Fluxus is a touchstone for many of their publications. But they also go beyond that paradigm with their use of contemporary technology, the way in which they craft their global artistic community, and the way they view their place in the complex history of art. -

Practices of Networking in Grassroots Communities from Mail Art to the Case of Anna Adamolo

Interface: a journal for and about social movements Article Volume 2 (2): 68 - 78 (November 2010) Bazzichelli, Critique of social networking Towards a critique of social networking: practices of networking in grassroots communities from mail art to the case of Anna Adamolo Tatiana Bazzichelli1 Abstract This article follows my reflections on the topic of networking art in grassroots communities as a challenge for socio-political transformation. It analyses techniques of networking developed in collective networks in the last half of the twentieth century, which inspired the structure of Web 2.0 platforms and have been used as a model to expand the markets of business enterprises. I aim to advance upon earlier studies on networked art, rejecting the widely accepted idea that social networking is mainly technologically determined. The aim is to reconstruct the roots of collaborative art practices in which the artist becomes a networker, a creator of shared networks that expand virally through collective interventions. The focus is collaborative networking projects such as the network of mail art and multiple identities projects such as the Luther Blissett Project (LBP), the Neoist network- web conspiracy and, referring to the contemporary scenario of social networking, the Italian case of Anna Adamolo (2008-2009). The Anna Adamolo case is presented as a clear example of how networking strategies, and viral communication techniques, might be used to generate political criticism both of the media (in this case of the social media) and society. This case study becomes even more relevant if framed by a long series of hacktivist practices realized in the Italian activist movement since the eighties, where collective and social interventions played a crucial role. -

Un Manifiesto Hacker

UN MANIFIESTO HACKER ALPHA. BET & GIMMEL McKENZIE WARK UN MANIFIESTO HACKER Traducción de Laura Mañero ALPHA DECAY Gracias a: AG, AR, BH, BL, CD, CF, el di funto CH, CL, CS, DB, DG, DS, FB, FS, GG, GL, HJ, IV, JB, JD, JF, JR, KH, KS, LW, MD, ME, MH, ML MT, MV, NR, OS, PM, RD, RG, RN, RS, SB, SD, SH, SK, SL, SS, TB, TC, TW. Versiones anteriores de Un manifiesto hacker aparecieron en Critical Secret, Feeler- gauge, Fibreculture Reader, Sarai Reader y Subsol In memoriam: Kathy Rey de los piratas Acker ÍNDICE Abstracción ..................................................................... 15 Clase.................................................................................. 23 Educación ....................................................................... 33 Hackear ........................................................................... 43 Historia ........................................................................... 53 Información..................................................................... 67 Naturaleza ....................................................................... 73 Producción....................................................................... 81 Propiedad ....................................................................... 89 Representación .............................................................. 103 Revuelta........................................................................... 113 Estado ............................................................................. 123 Sujeto.............................................................................. -

Fluxus Reader By: Ken Friedman Edited by Ken Friedman ISBN: 0471978582 See Detail of This Book on Amazon.Com

The Fluxus Reader By: Ken Friedman Edited by Ken Friedman ISBN: 0471978582 See detail of this book on Amazon.com Book served by AMAZON NOIR (www.amazon-noir.com) project by: PAOLO CIRIO paolocirio.net UBERMORGEN.COM ubermorgen.com ALESSANDRO LUDOVICO neural.it Page 1 PART I THREE HISTORIESPART I THREE HISTORIESPART I THREE HISTORIES Page 2 Page 3 Ben Patterson, Terry Reilly and Emmett Williams, of whose productions we will see this evening, pursue purposes already completely separate from Cage, though they have, however, a respectful affection.' After this introduction the concert itself began with a performance of Ben Patterson's Paper Piece. Two performers entered the stage from the wings carrying a large 3'x15' sheet of paper, which they then held over the heads of the front of the audience. At the same time, sounds of crumpling and tearing paper could be heard from behind the on-stage paper screen, in which a number of small holes began to appear. The piece of paper held over the audience's heads was then dropped as shreds and balls of paper were thrown over the screen and out into the audience. As the small holes grew larger, performers could be seen behind the screen. The initial two performers carried another large sheet out over the audience and from this a number of printed sheets of letter-sized paper were dumped onto the audience. On one side of these sheets was a kind of manifesto: "PURGE the world of bourgeois sickness, `intellectual', professional & commercialised culture, PURGE the world of dead art, imitation, artificial art, abstract art, illusionistic Page 4 [...] FUSE the cadres of cultural, social & political revolutionaries into united front & action."2 The performance of Paper Piece ended as the paper screen was gradually torn to shreds, leaving a paper-strewn stage.