Practices of Networking in Grassroots Communities from Mail Art to the Case of Anna Adamolo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collaborative “Mail Art” Puts the Post in Postmodernism Letters, Envelopes and Enclosures Take Center Stage in an Intimate New Art Show

Collaborative “Mail Art” Puts the Post in Postmodernism Letters, envelopes and enclosures take center stage in an intimate new art show Envelope decoration was always a staple of the mail art experience. This colorful letter was sent from performance artist Anna Banana (Anna Lee Long) to collagist John Evans in 2010. (John Evans papers, Archives of American Art). By Ryan P. Smith JULY 30, 2018 In the era of instant messaging and FaceTime on the go, it can be easy to forget the pleasure of shuffling out to the mailbox in hope of discovering a thoughtful note from an old friend. Removing a letter from its envelope is a rich tactile experience, and marginalia, cross-outs, distinct penmanship and quirky enclosures combine to give epistolary exchanges a uniquely personal flavor. In the experimental artistic simmer of the late 1950s, the everyday creativity of letter-writing gave rise to a veritable movement: that of “mail art,” an antiestablishment, anything-goes mode of serial imaginative expression whose inclusive nature has kept it alive even into the Digital Age. Now a new show, “Pushing the Envelope,” organized by the Smithsonian's Achives of 2018 American Art and opening August 10 at the Lawrence A. Fleischman Gallery in Washington, D.C., promises to shine a spotlight on the medium. The enigmatic Neo-Dada collagist Ray Johnson, a Detroit native who struggled with fame even as he appropriated images of movie stars for his art, pioneered in the field of mail art, weaving together an immense spider web of collaborators that would survive him following his sudden suicide in 1995. -

The Healthcare Riskops Manifesto

The Healthcare RiskOps Manifesto “Committees are, by nature, timid. They are based on the premise of safety in numbers; content to survive inconspicuously, rather than take risks and move independently ahead. Without independence, without the freedom for new ideas to be tried, to fail, and to ultimately succeed, the world will not move ahead, but rather live in fear of its own potential” Ferdinand Porsche And you may ask yourself, "How do I work this?" And you may ask yourself, "Where is that large automobile?" And you may tell yourself, "This is not my beautiful house." And you may tell yourself, "This is not my beautiful wife." David Byrne The End is Near “People of Earth, hear this!” A specter is haunting healthcare. And we’ve got work to do. It’s about challenging the old assumptions of managing risk because nothing has changed. Yet, everything has changed. It’s about heralding a new vision because the old one doesn’t work. Change creates opportunities. Change drives outcomes. And healthcare needs secure outcomes. Healthcare risk needs change. We must challenge assumptions: identity, role, purpose, place, power. Change built on strong beliefs that will upset the status quo. We don’t care. We are focused on moving the industry forward. Le risque est avant-gardiste. Futurism. Vorticism. Dada. Surrealism. Situationism. Neoism. Risk the Elephant. Uncaged. Risk is Nazaré. It’s a red balloon. Risk is sunflower fields. And fire on the mountain. Risk guides the first decision. It’s as old as Eden. Fight. Or flight. Risk is nucleotide. To ego. -

Danish Artists in the International Mail Art Network Charlotte Greve

Danish Artists in the International Mail Art Network Charlotte Greve According to one definition of mail art, it is with the simple means of one or more elements of the postal language that artists communicate an idea in a concise form to other members of the mail art network.1 The network constitutes an alternative gallery space outside the official art institution; it claims to be an anti-bureaucratic, anti-hierarchic, anti-historicist, trans-national, global counter-culture. Accordingly, transcendence of boundaries and a destructive relationship to stable forms and structures are important elements of its Fluxus-inspired idealistic self-understanding.2 The mail art artist and art historian Géza Perneczky describes the network as “an imaginary community which has created a second publicity through its international membership and ever expanding dimensions”.3 It is a utopian artistic community with a striving towards decentralized expansion built on sharing, giving and exchanging art through the postal system. A culture of circulation is built up around a notion of what I will call sendable art. According to this notion, distance, delay and anticipation add signification to the work of art. Since the artists rarely meet in flesh and blood and the only means of communication is through posted mail, distance and a temporal gap between sending and receiving are important constitutive conditions for the network communication. In addition, very simple elements of the mail art language gain the status of signs of subjectivity, which, in turn, become constitutive marks of belonging. These are the features which will be the focus of this investigation of the participation of the Danish artists Mogens Otto Nielsen, Niels Lomholt and Carsten Schmidt-Olsen in the network during the period from 1974–1985. -

Urban Legends

Jestice/English 1 Urban Legends An urban legend, urban myth, urban tale, or contemporary legend is a form of modern folklore consisting of stories that may or may not have been believed by their tellers to be true. As with all folklore and mythology, the designation suggests nothing about the story's veracity, but merely that it is in circulation, exhibits variation over time, and carries some significance that motivates the community in preserving and propagating it. Despite its name, an urban legend does not necessarily originate in an urban area. Rather, the term is used to differentiate modern legend from traditional folklore in pre-industrial times. For this reason, sociologists and folklorists prefer the term contemporary legend. Urban legends are sometimes repeated in news stories and, in recent years, distributed by e-mail. People frequently allege that such tales happened to a "friend of a friend"; so often, in fact, that "friend of a friend has become a commonly used term when recounting this type of story. Some urban legends have passed through the years with only minor changes to suit regional variations. One example is the story of a woman killed by spiders nesting in her elaborate hairdo. More recent legends tend to reflect modern circumstances, like the story of people ambushed, anesthetized, and waking up minus one kidney, which was surgically removed for transplantation--"The Kidney Heist." The term “urban legend,” as used by folklorists, has appeared in print since at least 1968. Jan Harold Brunvand, professor of English at the University of Utah, introduced the term to the general public in a series of popular books published beginning in 1981. -

Mail a D News

Mail Ad News Stamp Art Gallery The Stamp Art Gallery has a The Ray Johnson Award, initiated by Edition Janus, checklist of Stamp Art Editions, which they have been for $2000 prize honoring outstanding contributions to publishing over the past three years. Included are correspondence or mail art, was established in 1995. catalogs of the stamp works of Joseph Beuys, Mike Edition Janus now invites anyone to join the ongoing Crane, the Fake Picabia Brothers, S. Gustav Hagglund, correspondence. Submissions of original artwork, Graf Waufer, J.H. Kocman, Henning Mittendorf, Kurt preferably in postcard format, are always welcome for Schwitters, Serge Segay and Endre Tot, among others. kture awards. All mail will be acknowledged. Send to For the list and for purchase ($15.00 for each catalog), Edition Janus, Eberhard Janke, Namslaustr. 85, 13507 write to Stamp Art Gallery, 466 8th St., San Francisco, Berlin, Germany. CA 94103. A special catalog of lives Klein has been published for $19.95 and a Klein box costs $14.95 for a The L World: Artist-Valentines for the 90's. On special rubberstamp. The Robert Watts Catalog costs Valentine's Day, 14 February 1996, forty artists were $23.95. The Ken Friedman Catalog and set of invited to create works based on contemporary notions rubberstamps costs $80.00 (ed. of 50) In March, the of love and romance. Additionally, many of the invited Stamp Art Gallery presented Donald Evans: Catalogue artists were utilizing video, video installations, digitized of the World as well as rubber stamps by Andrej Tisma. photography and mixed media light installations giving In April, Terra Candella (Harley), M.B. -

Fact Or Fiction?

The Ins and Outs of Media Literacy 1 Part 1: Fact or Fiction? Fake News, Alternative Facts, and other False Information By Jeff Rand La Crosse Public Library 2 Goals To give you the knowledge and tools to be a better evaluator of information Make you an agent in the fight against falsehood 3 Ground rules Our focus is knowledge and tools, not individuals You may see words and images that disturb you or do not agree with your point of view No political arguments Agree 4 Historical Context “No one in this world . has ever lost money by underestimating the intelligence of the great masses of plain people.” (H. L. Mencken, September 19, 1926) 5 What is happening now and why 6 Shift from “Old” to “New” Media Business/Professional Individual/Social Newspapers Facebook Magazines Twitter Television Websites/blogs Radio 7 News Platforms 8 Who is your news source? Professional? Personal? Educated Trained Experienced Supervised With a code of ethics https://www.spj.org/ethicscode.asp 9 Social Media & News 10 Facebook & Fake News 11 Veles, Macedonia 12 Filtering Based on: Creates filter bubbles Your location Previous searches Previous clicks Previous purchases Overall popularity 13 Echo chamber effect 14 Repetition theory Coke is the real thing. Coke is the real thing. Coke is the real thing. Coke is the real thing. Coke is the real thing. 15 Our tendencies Filter bubbles: not going outside of your own beliefs Echo chambers: repeating whatever you agree with to the exclusion of everything else Information avoidance: just picking what you agree with and ignoring everything else Satisficing: stopping when the first result agrees with your thinking and not researching further Instant gratification: clicking “Like” and “Share” without thinking (Dr. -

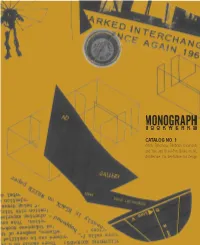

CATALOG NO. 1 Artists’ Ephemera, Exhibition Documents and Rare and Out-Of-Print Books on Art, Architecture, Counter-Culture and Design 1

CATALOG NO. 1 Artists’ Ephemera, Exhibition Documents and Rare and Out-of-Print Books on Art, Architecture, Counter-Culture and Design 1. IMAGE BANK PENCILS Vancouver Canada Circa 1970. Embossed Pencils, one red and one blue. 7.5 x .25” diameter (19 x 6.4 cm). Fine, unused and unsharpened. $200 Influenced by their correspondence with Ray Johnson, Michael Morris and Vincent Trasov co- founded Image Bank in 1969 in Vancouver, Canada. Paralleling the rise of mail art, Image Bank was a collaborative, postal-based exchange system between artists; activities included requests lists that were published in FILE Magazine, along with publications and documents which directed the exchange of images, information, and ideas. The aim of Image Bank was an inherently anti- capitalistic collective for creative conscious. 2. AUGUSTO DE CAMPOS: CIDADE=CITY=CITÉ Edinburgh Scotland 1963/1964. Concrete Poem, letterpressed. 20 x 8” (50.8 x 20.3 cm) when unfolded. Very Good, folded as issued, some toning at edges, very slight soft creasing at folds and edges. $225. An early concrete poetry work by Augusto de Campos and published by Ian Hamilton Finlay’s Wild Hawthorn Press. Campos is credited as a co-founder (along with his brother Haroldo) of the concrete poetry movement in Brazil. His work with the poem Cidade=City=Cité spanned many years, and included various manifestations: in print (1960s), plurivocal readings and performances (1980s-1990s), and sculpture (1987, São Paulo Biennial). The poem contains only prefixes in the languages of Portuguese, English and French which are each added to the suxes of cidade, city and cité to form trios of words with the same meaning in each language. -

“La Llorona” As a Liminal Archetypal Monster in Modern Latin American Society

eTropic 16.1 (2017): ‘Tropical Liminal: Urban Vampires & Other Bloodsucking Monstrosities’ Special Issue | 67 The Role of the Internet in the Endurance of “La Llorona” as a Liminal Archetypal Monster in Modern Latin American Society David Ramírez Plascencia University of Guadalajara-SUV, México Abstract Monsters are liminal beings that not only portray fears, proscriptions and collective norms, they are also embedded with special qualities that scare and, at the same time, captivate people’s inquisitiveness. Monstrosities are present in practically all cultures; they remain alive, being passed from one generation to another, often altering their characteristics over time. Modernity and science have not ended people’s belief in paranormal beings; to the contrary, they are still vivid and fresh, with contemporary societies updating and incorporating them into daily life. This paper analyses one of the most well-known legends of Mexico and Latin America, the ghost of “La Llorona” (the weeping woman). The legend of La Llorona can be traced to pre-Hispanic cultures in Mexico, however, the presence of a phantasmagoric figure chasing strangers in rural and urban places has spread across the continent, from Mexico and Central America, to Latino communities in the United States of America. The study of this liminal creature aims to provide a deep sense of her characteristics – through spaces, qualities and meanings; and to furthermore understand how contemporary societies have adopted and modernised this figure, including through the internet. The paper analyses different versions of the legend shared across online platforms and are analysed using Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s (1996) theoretical tool described in his work Monster Culture (Seven Theses), which demonstrates La Llorona’s liminal qualities. -

Experiments in Clustering Urban-Legend Texts

How to Distinguish a Kidney Theft from a Death Car? Experiments in Clustering Urban-Legend Texts Roman Grundkiewicz, Filip Gralinski´ Adam Mickiewicz University Faculty of Mathematics and Computer Science Poznan,´ Poland [email protected], [email protected] Abstract is much easier to tap than the oral one, it becomes feasible to envisage a system for the machine iden- This paper discusses a system for auto- tification and collection of urban-legend texts. In matic clustering of urban-legend texts. Ur- this paper, we discuss the first steps into the cre- ban legend (UL) is a short story set in ation of such a system. We concentrate on the task the present day, believed by its tellers to of clustering of urban legends, trying to reproduce be true and spreading spontaneously from automatically the results of manual categorisation person to person. A corpus of Polish UL of urban-legend texts done by folklorists. texts was collected from message boards In Sec. 2 a corpus of 697 Polish urban-legend and blogs. Each text was manually as- texts is presented. The techniques used in pre- signed to one story type. The aim of processing the corpus texts are discussed in Sec. 3, the presented system is to reconstruct the whereas the clustering process – in Sec. 4. We manual grouping of texts. It turned out that present the clustering experiment in Sec. 5 and the automatic clustering of UL texts is feasible results – in Sec. 6. but it requires techniques different from the ones used for clustering e.g. news ar- 2 Corpus ticles. -

Storytelling

Please do not remove this page Storytelling Anderson, Katie Elson https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643385580004646?l#13643502170004646 Anderson, K. E. (2010). Storytelling. SAGE. https://doi.org/10.7282/T35T3HSK This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/09/24 13:02:38 -0400 Chapter 28- 21st Century Anthropology: A Reference Handbook Edited by H. James Birx Storytelling Katie Elson Anderson, Rutgers University. Once upon a time before words were written, before cultures and societies were observed and analyzed there was storytelling. Storytelling has been a part of humanity since people were able to communicate and respond to the basic biological urge to explain, educate and enlighten. Cave drawings, traditional dances, poems, songs, and chants are all examples of early storytelling. Stories pass on historical, cultural, and moral information and provide escape and relief from the everyday struggle to survive. Storytelling takes place in all cultures in a variety of different forms. Studying these forms requires an interdisciplinary approach involving anthropology, psychology, linguistics, history, library science, theater, media studies and other related disciplines. New technologies and new approaches have brought about a renewed interest in the varied aspects and elements of storytelling, broadening our understanding and appreciation of its complexity. What is Storytelling? Defining storytelling is not a simple matter. Scholars from a variety of disciplines, professional and amateur storytellers, and members of the communities where the stories dwell have not come to a consensus on what defines storytelling. -

Agregue Y Devuelva, MAIL ART En Las Colección Del MIDE-CIANT/UCLM

AGREGUE Y DEVUELVA MAIL ART en las colecciones del MIDE-CIANT/UCLM © de los textos e ilustraciones: sus autores. © de la edición: Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha. Textos de: José Emilio Antón, Ibírico, Ana Navarrete Tudela, Sylvia Ramírez Monroy, César Reglero y Pere Sousa. Edita: Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, MIDE-CIANT y Fundación Antonio Pérez. Colección CALEIDOSCOPIO n.º 17. Serie Cuadernos del Media Art. Dir.: Ana Navarrete Tudela Equipo de documentación: Ana Alarcón Vieco, Roberto J. Alcalde López y Clara Rodrigo Rodríguez. Fotografías: Montserrat de Pablo Moya Corrección de textos: Antonio Fernández Vicente I.S.B.N.: 978-84-9044-421-4 (Edición impresa) I.S.B.N.: 978-84-9044-422-1 (Edición electrónica) Doi: http://doi.org/10.18239/caleidos_2021.17.00 D.L.: CU 11-2021 Esta editorial es miembro de la UNE, lo que garantiza la difusión y comercialización de sus publicaciones a nivel nacional e internacional. Diseño y maquetación: CIDI (UCLM) Impresión: Trisorgar Artes Gráficas Hecho en España (U.E.) – Made in Spain (E.U.) Esta obra se encuentra bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons CC BY 4.0. Cualquier forma de reproducción, distribución, comunicación pública o transformación de esta obra no incluida en la licencia Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 solo puede ser realizada con la autorización expresa de los titulares, salvo excepción prevista por la ley. Puede Vd. acceder al texto completo de la licencia en este enlace: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.es EXPOSICIONES: Comisariado: Patricia Aragón Martín, Ana Navarrete Tudela, Montserrat de Pablo Moya Coordinación: Ana Navarrete Tudela Ayudantes de coordinación: Adoración Saiz Cañas, Ana Alarcón Vieco, Ignacio Page Valero Dirección de montaje: MIDE-CIANT/UCLM, Fundación Antonio Pérez, ArteTinta Digitalización: Ana Alarcón Vieco, Patricia Aragón y Clara Rodrigo Rodríguez Montaje y transporte: ArteTinta Centros: Sala ACUA, Cuenca. -

Urban-Legend-PUPIL.Pdf

PUPIL Like the wood we use for our furniture, the paper used to print this catalog is FSC certified and comes from responsible forests. OUR BRAND VALUES Urban Legend, a brand by CasaMia Interior Ltd. Born from the will to create accessible Designs that do not compromise innovation, quality and style, “Urban Legend” is a freedom brand first and foremost We create what we like. We believe the best way to keep our innovative and creative spirit alive every day is to love what we do, and to do it with purpose. We constantly re-invent ourselves. Our Designs cannot be classified under one particular style, but rather incorporate different languages to create unique statements. Our Design vision is very focused on what we call our “emotional intelligence”, or our capacity to be moved by a simple detail, a shape or a texture. Our style is minimalist yet sophisticated, warm and “There is an invisible, subconscious authentic yet resolutely contemporary, innova- tive and sometimes conservative. These contra- feeling that connects us to the dictions, we do not fight them, but we integrate things we love. It is this very intimate them fully into our work, and they define the very and ethereal emotion that we strive unique “Urban Legend” signature, between Arti- san well kept knowhow and “modern lifestyles”. to ignite through our products” D.Jamet Head of Design p4 p5 OUR PRODUCTS Our furniture is manufactured in Vietnam, by “work- shop-sized” facturies that are both highly skilled and cost-efficient. We put a high priority to work with people who take pride in what they do, and always / FSC timbers aim at achieving higher goals with us! / Human-scaled 100% of the wood we use in production is imported and comes from sustainable forests.